Sweet, Hot And Sassy—Shirley MacLaine

The turning point in the career of Shirley MacLaine, new Wallis-Paramount star, came at the most unexpected moment. She was on a Seventh Avenue subway in New York when the motor suddenly conked out, and the train stalled in the tunnel.

With only seconds to spare this meant catastrophe. She would be late for the evening performance of “The Pajama Game,” where she was a specialty dancer and understudy to Miss Carol Haney. “There goes my job,” she fretted frantically, looking with revulsion at the peanut butter sandwich she was munching on. For the past two years she had practically existed on them and the mere thought of more dreary months of such fare seemed more than she could bear. Tears streamed down her cheeks as she sat huddled in a corner of the subway car.

Twenty precious minutes later and all but the las hope gone, she was tearing through the Times Square crush, knocking startled pedestrians out of her path, running like a scared cat.

Arriving at the theatre, panting with near exhaustion, she was greeted by a half-demented stage manager who was tearing out handfuls of hair and screaming, “Where have you been? Haney sprained her ankle and you’re on!”

“I got into something, not knowing whether it was a costume or a bathing suit,” Shirley said, “and before I knew what had happened I was out there on the stage, staring into that sea of upturned faces, my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth and my legs turned to jelly. In the wings were the other members of the cast, their eyes fixed on me imploringly. It was only the third night after the opening and I knew they had all kissed their jobs goodbye.

“When the curtain fell on the first act, I knew I was in. The burst of applause surging up from the audience was the sweetest music I ever heard. The cast knew it, too. They crowded round me and a couple of veterans touched my shoulder and said, ‘Nice work, kid.’ That was the highest!”

The next two acts for Shirley were a breeze, and when it was all over, she was soaring above that never-never land of dreams-come-true. “I was a little drunk with excitement,” she said, “and I didn’t want that wonderful moment to end. I wanted it to go on forever.”

It was precisely at this instant that fate—or the kindly providence that cares for actors and children—intervened once more. Hal Wallis, famed producer on the Paramount lot who had journeyed East to look over Carol Haney, remained to watch Shirley. When the show was over, he strolled backstage, and Shirley, spotting him, asked with naivete, “Were you looking for me?”

Wallis, who had discovered such luminaries as Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Shirley Booth, Lizabeth Scott, Kirk Douglas and many others, signed her almost on the spot. Her subsequent screen test, directed by Daniel Mann, confirmed his quick judgment: She was a find!

For a month Miss MacLaine continued to dazzle the jaded eyes of Broadway. Then Carol Haney recovered and Shirley stepped back into the chorus.

One night in September, Miss Haney was forced to drop out of the cast again and once more Shirley’s good fairy waved her wand. A New York representative of producer-director Alfred Hitchcock was in the audience to appraise Miss Haney. He was so bemused by the brash youngster substituting for her that afterward he wired his superior, somewhat ecstatically, that he had seen a sprite with steel springs in her long legs who could not only dance but sing and act like a house afire. Hitchcock, a skeptical realist who believes that sprites and elves are found only beneath thorn bushes in Ireland, hopped a plane for New York. There, to his dismay, he found that she was already signed by the ubiquitous Mr. Wallis. Telegrams crackled between Los Angeles and Bagdad-on-Hudson, and at last Miss MacLaine was secured for Hitchcock’s new picture, “The Trouble with Harry.”

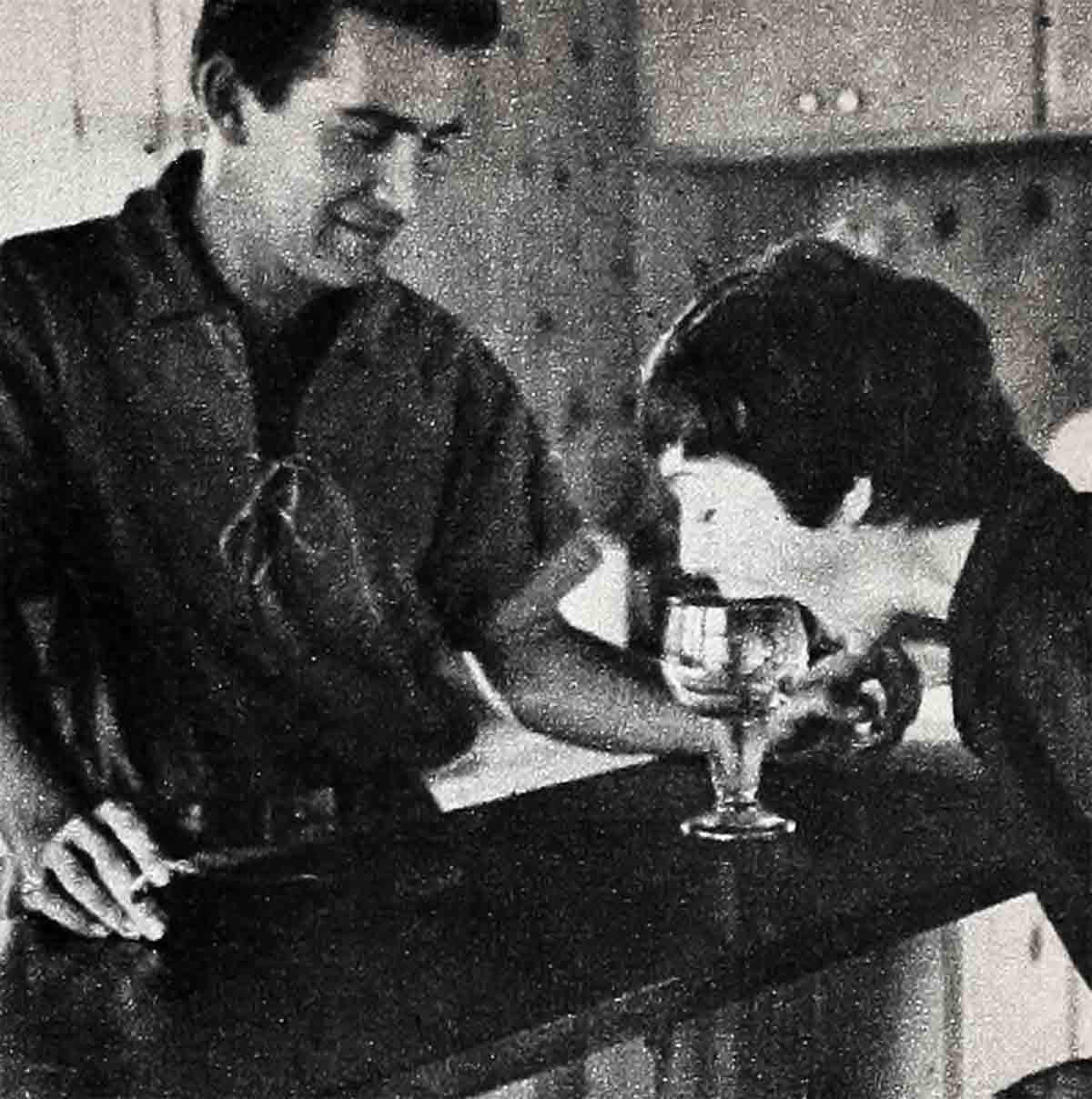

Just prior to Hitchcock’s advent upon the scene, Shirley had met a young actor-director named Steve Parker. “We bumped’ into each other in a soda bar,” Steve said. “She seemed to be trying to swallow the glass. Shirley has the widest mouth in the business, this side of Martha Raye, and I watched her in fascination as she got the entire end of the glass between her teeth. I went over and stood beside her, afraid to speak lest she’d bite down on it and cut her lip. She tired of the trick after a while and I said, ‘Look, kid, don’t you know that glass isn’t good to eat?’

“She glanced up then and I got my first good look at her pixyish, slant-eyed face. I guess something happened to me at that moment. Anyway, I was in one of the front rows at ‘The Pajama Game’ every night from then on.”

“My luck was still in,” said Shirley. “Steve saved me from being just another flash-in-the-pan. He taught me to speak, literally, not chew words or spit them out like something I wanted to get rid of. After every performance, Steve went with me to my cheap little apartment and worked me like a slave. I improved so, eager chorines began coming to me after the show and asking who my dramatic coach was.”

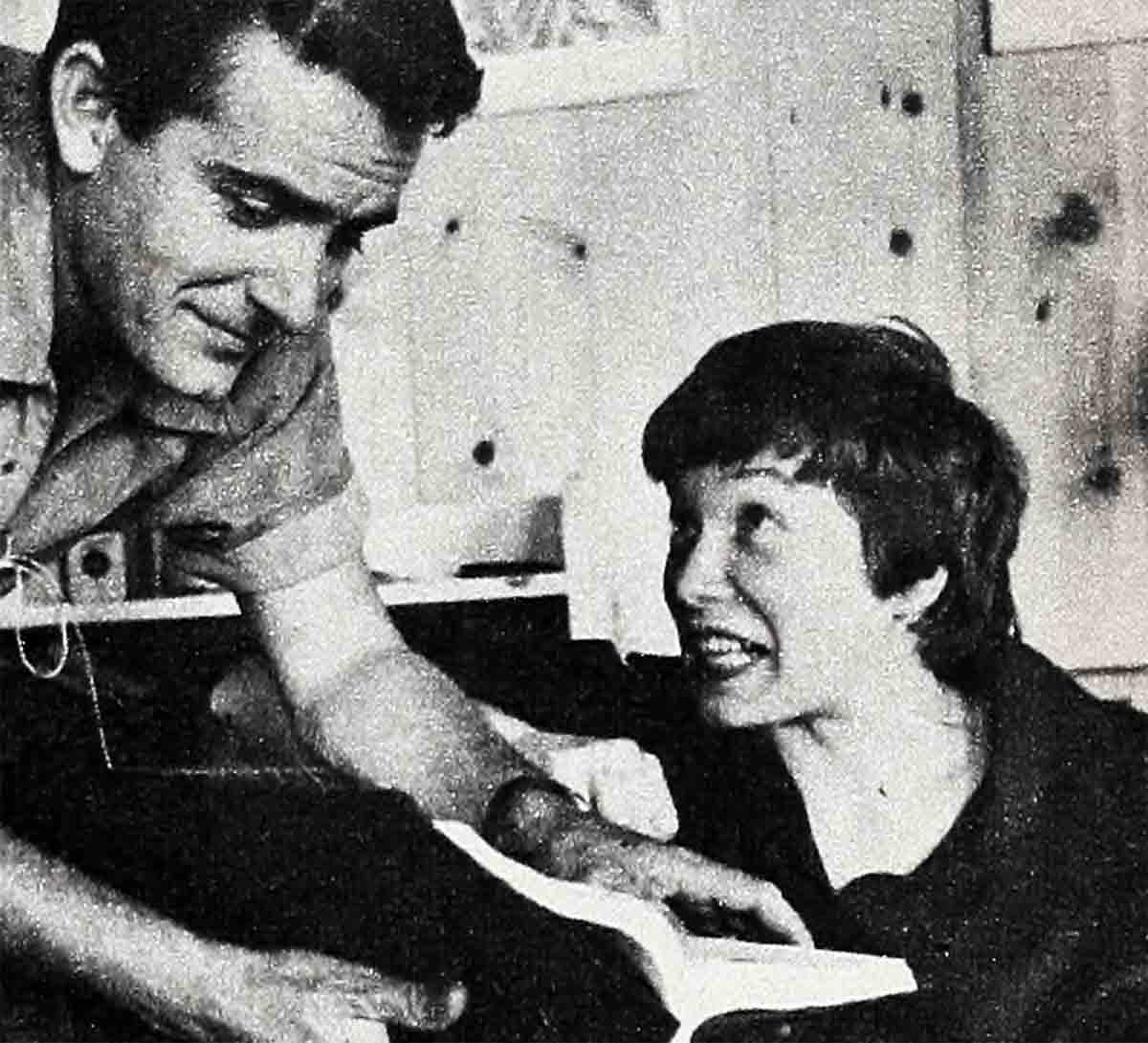

When Shirley went to Vermont to make “The Trouble with Harry,” Steve followed her. They were married September 17, 1954. Since then Steve has been her personal director-manager, a function which he pursues simultaneously with efforts to start a little theatre in Malibu. There he and Shirley live in a little house. The place is tiny—you’d hardly dare to let your pants get baggy in it—but the view is magnificent. On bright days the great Pacific crinkles in millions of iridescent prisms of light. When there’s a big roll coming in, the breakers bellow with an almost soothing cadence. “It’s a little far from the studio,” Shirley admits, “but it helps one to remember that Hollywood isn’t so terribly important in the great scheme of things after all.”

It is this cool objectivity of Miss MacLaine’s which gives the high Pooh-Bahs of her studio pause. They watch her expressive face, mirroring every fleeting emotion and ask themselves apprehensively if this could mean temperament. “She has a little trick of ‘going away’ when you’re talking to her,” one of them said. “You don’t know if she’s listening or considering some crazy thing like selecting her own roles.” Actually she is probably only thinking how nice it would be if she could just stay home and have babies. She readily admits she’d like to have three.

“My idea of real fun,” Shirley said, hiking her long legs, encased in tight-fitting Capri pants, over the arm of her chair, “would be to go uranium hunting with Steve. I’d like to do all the time what most people accomplish only on vacations—fishing, camping or hiking in the mountains. We talk a lot about getting on a tramp steamer and going to Asia—you know, the ‘slow boat to China’ routine. Maybe we’ll do it sometime, too.”

All this, to studio people, is highly revolutionary. What, they ask themselves with almost pathetic conviction, could be better than making pictures in Hollywood?

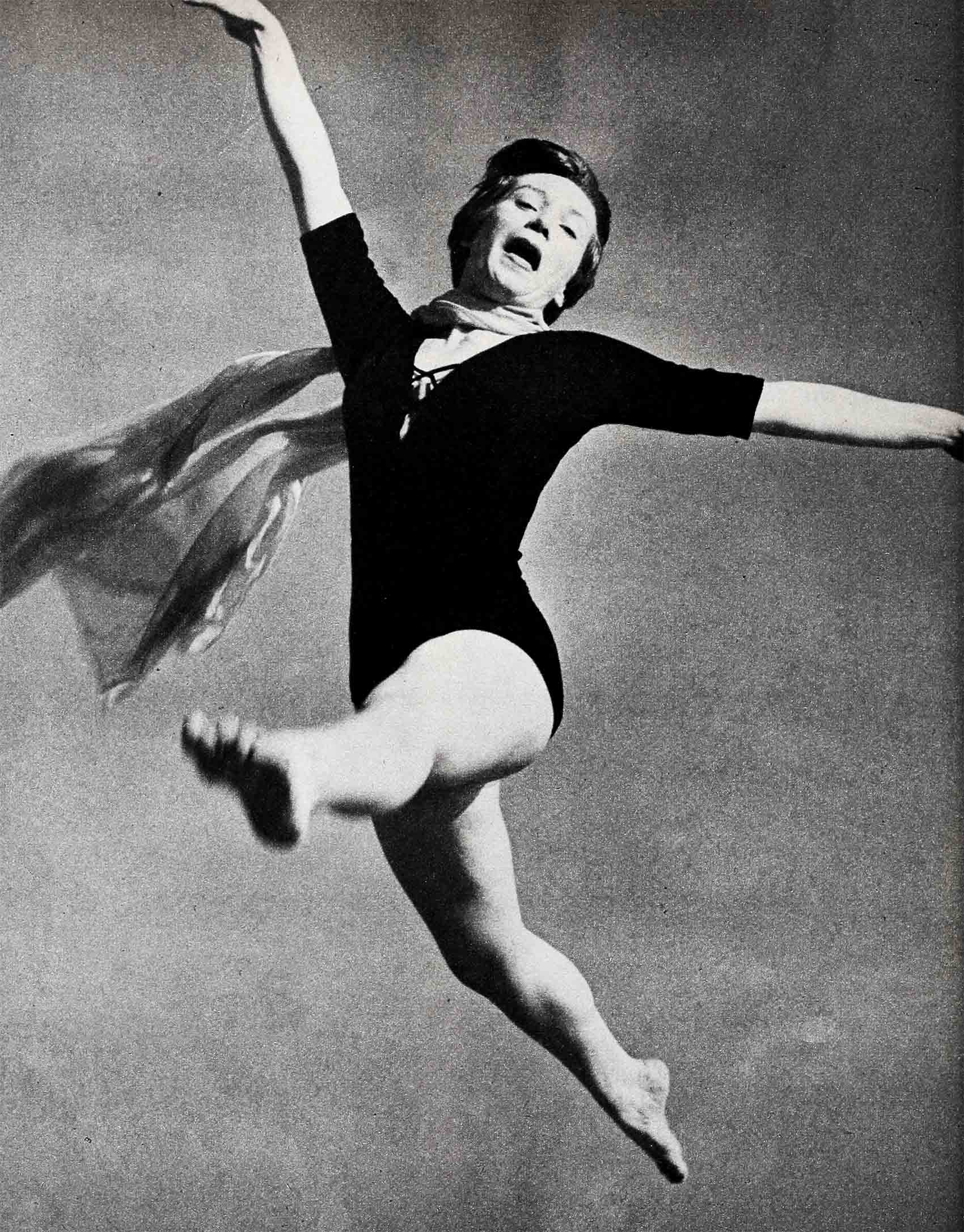

Those who believe that Shirley has a tremendous future before her in films—and they are many—attribute these longings to youth and the deluge of publicity which has recently descended upon her cropped head. After she co-starred with Martin and Lewis in “Artists and Models,” a national magazine described her as one of the brightest new stars of the year. She has heard her figure (5‘6”, 34”-24”-34”) hailed as the most perfect in Hollywood, her face a composite of Audrey Hepburn’s, Claudette Colbert’s and Diana Lynn’s and her gamin personality so refreshing and appealing that she actually resembles no one unless it be the sprightly elves that are supposed to inhabit her forbears’ native Scotland and Ireland. Frank Tashlin, director of “Artists and Models,” became quite lyrical. “Find a large mushroom,” he said, “put Shirley on it and you have the perfect pixie.”

Such tall talk has unsettled many an older head but not Shirley’s. She can still remember her two-year diet of peanut butter sandwiches with horror. “I spent every cent of my salary as a chorus girl,” she says, “except the bare amount necessary to stay alive, on dancing, singing and dramatic lessons. So with only a dime for lunch I used to go to the Automat, buy a peanut butter sandwich, snitch one of those ice tea glasses that always have a segment of lemon stuck on the rim. This I filled half full of water, took to a table, put in three teaspoons of sugar and squeezed my lemon into it. In a jiffy I had myself a lemonade. That kind of scrimping paid off because when my break came, the lessons got me over the hill. You have to pay the price if you don’t want to spend your youth in a chorus line.”

Arriving in the cinema capital with no more wardrobe than a half-starved sparrow—you don’t buy much frippery on a chorus girl’s salary—she and her young husband sought and found their little dream house on Malibu Beach. There, for a time, she twiddled her thumbs, dreading the call to work which would start her swimming upstream in the biggest goldfish bowl in the world. Soon, however, she began to worry on quite another score—the call didn’t come. Weeks passed without so much as a nod from the publicity department and she began to envision being shipped back to New York and the chorus line.

Then one day, two weeks before going into “Artists and Models,” everybody, at once, seemed to discover her. A couple of newspaper writers saw her screen test—a charming informal dance step without music and small talk about herself—and left the test projection room beguiled. Soon cropping up in their columns was the name Shirley MacLaine. She made good copy. With a strong streak of individuality, she’d argue a point, insist upon the truth, let the press in on her idiosyncrasies—like taking off her wedding ring and handing it to her husband before going onto the set. Directors and producers needing new talent found her a tonic.

Suddenly, Shirley had more work than she could do. She was forced to turn down the lead in “Bus Stop” (her contract with Wallis permits her to make only one picture a year on the outside). She tested for “The Rainmaker,” a role Shirley admits she’d give up her trip to China to get. At the end of her first year under contract, she will have made four pictures, “The Trouble with Harry,” “Artists and Models,” and two more not, as yet, decided upon. The cost will be $20,000,000.

How has all this affected Shirley? It hasn’t touched her. She would still rather eat lunch in the Paramount commissary with an obscure but talented actor whom she knew in New York than at the big table where the high and mighty gather. She dodges big parties and abhors smart Hollywood chatter because, she says, it is insincere. “I don’t know how to handle flip talk,” she stated, “and off-color stories just make me mad. I don’t drink because I think it’s silly. So, you see, I’m a dud at big crushes.”

Her disinclination to look or act like a typical Hollywood star sometimes results in amusing frustrations. One of these occurred at the recent Academy Awards blow-out. Shirley and her husband attempted to pass down the lane reserved for the screen elect when they were halted by a policeman. In all fairness, it must be stated, the cop was justified. Shirley, dressed in a simple frock, which she might have worn for a quiet dinner at home, in no way resembled the glittering personalities who shone in the bright glare of exploding flashlight bulbs. “Wrong pew, girlie,” he growled, “get back where you belong.”

“But I do belong here,” she protested.

“Look, kid,” the officer said, “I know a star when I see one—and you ain’t no star.”

Shirley, who still gets most of her clothes from the studio wardrobe, smiled quietly and took her place with the ordinary mortals in the lobby of the Pantages Theatre.

Miss MacLaine, born Shirley Beaty, in Richmond, Virginia, April 24, 1934, is the daughter of Ira O. Beaty, a former musician and band leader now a real-estate agent in Arlington, Virginia. Her mother is the former Kathlyn MacLean, who once acted in little theatres at Toronto, Canada, and taught dramatics at Maryland College. She has a brother, Warren, 17, trying to decide between being a jazz musician or a lawyer.

When she was three years old her show-people parents started her in ballet lessons and she made her first professional appearance at four in the famous Mosque recitals at Richmond. She attended Washington and Lee High School, Arlington, and was cheer leader and avid participant in most school activities.

In 1950, and not yet out of high school, she went to New York and immediately got work in the chorus for a revival of “Oklahoma!” Later she was in the chorus of “Kiss Me Kate” at St. John Terrell’s Music Circus at Lambertville, New Jersey.

Returning home she finished high school and set out for New York again. She auditioned and auditioned and finally got a job in an electrical appliance trade show, demonstrating refrigerators by dancing and prancing around them. One special routine had 55 consecutive ballet turns. “Enough,” she said, “to whip cream in a box if I’d been geared.”

She did guest shots on TV, modeled for stores and photographers, danced summers with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and got her first good job in New York in the chorus of “Me and Juliet.” She stayed with it until Frederick Brisson accepted her for “The Pajama Game.”

What the future holds for Shirley MacLaine is still in the lap of the theatrical gods. But one thing is certain. She’ll never, never have to eat another peanut butter sandwich.

THE END

—BY JOHN MUNDY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1955

No Comments