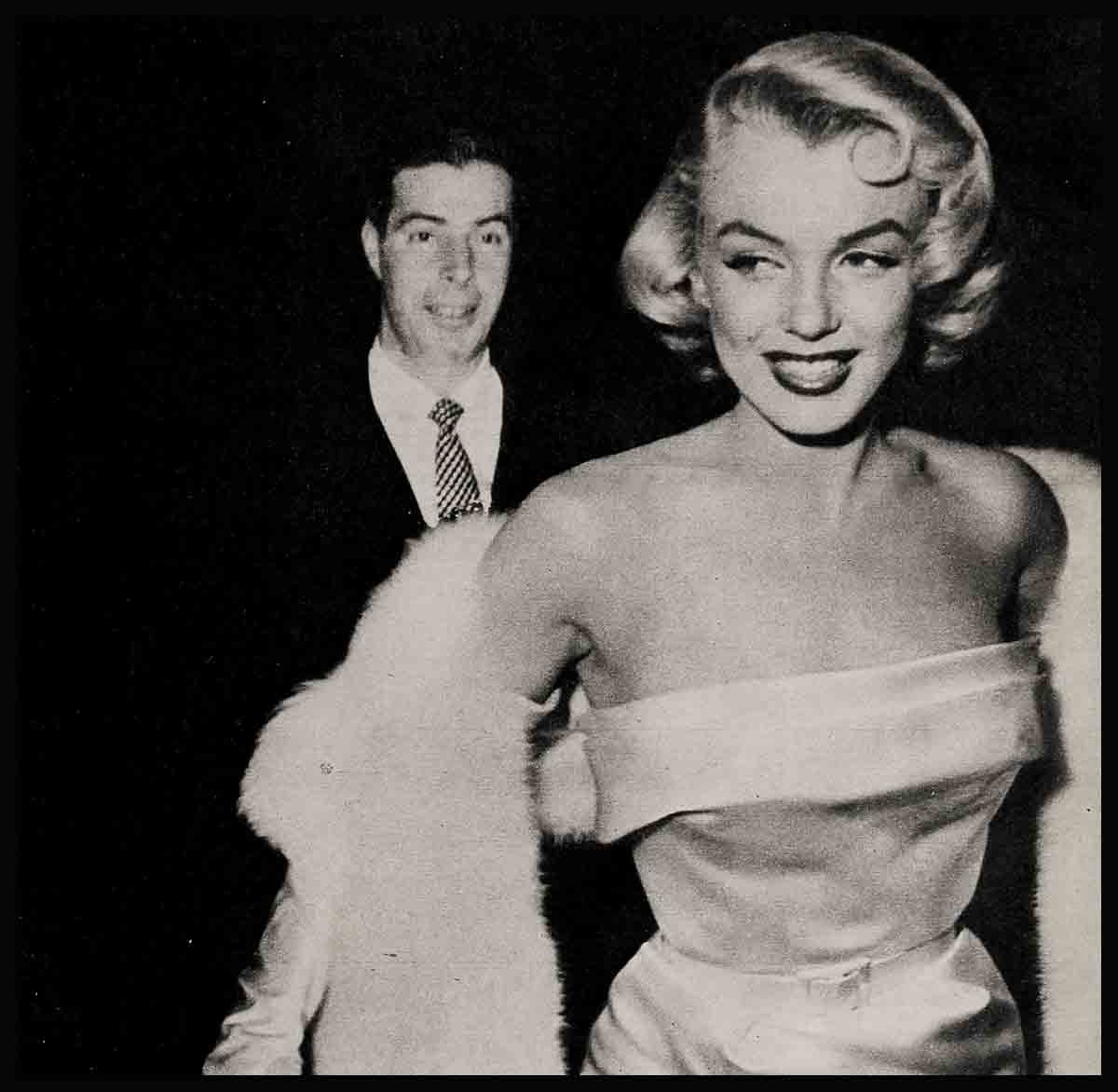

The Two Worlds Of Marilyn Monroe

Since her wedding Marilyn Monroe has been living in two worlds. One is at home with Joe in the evening—which she considers most important—and the other is her own daytime career world which keeps her famous and content.

These two worlds are separate and Joe wants Marilyn to keep them that way. And she, of course, is willing.

The vital question is: Are these two worlds antagonistic or complementary?

Can Marilyn be one sort of woman during the day and another sort at night?

Can she have one set of friends from eight A.M. to six P.M. and another set from six to midnight?

The chances are good that as you read this, Joe and Marilyn have been separated, geographically speaking.

Joe should be somewhere in the east covering the World Series, and Marilyn should be somewhere in the west making a comedy called The Seven Year Itch.

It is probable, too, that you will read—in fact, may already have read—that the DiMaggio marriage isn’t exactly paradise. The idyllic twosome has become more realistic with the passage of time, which is the normal course of marriage.

But Marilyn’s marriage happens to be unusual in several ways.

She married a great athlete who was already retired when she met him. At the time of their marriage, January 14, 1954, Marilyn was approaching the zenith of her career; her husband no longer had one.

Besides their mounting and undeniable love for each other, the DiMaggios have relatively little in common. Joe knows very little about acting and dramatics, and Marilyn knows just as little about baseball.

Marilyn has no intention, certainly, of becoming an athlete, and Joe refuses to try to mastermind his wife’s career.

Joe and Marilyn have completely different backgrounds. Joe was raised in a large, happy, healthy household filled with laughter and companionship. Marilyn lived the youth of an unwanted orphan, alone, afraid, insecure. Because of all this, some people are now saying trouble will come.

Some of these have gone so far as to suggest that Joe is jealous of his wife.

“Why,” they ask, “does he refuse to visit her on the set? Is that normal for a loving husband?”

They ask further, “Why won’t he pose with her for home layouts? Why does he object to publicity? One of his best friends, a sports writer, telephoned from New York and asked if he’d pose for some photos. Why should Joe turn down his friend?

“Why won’t he take Marilyn to parties or previews or premieres? Why won’t he make the slightest sacrifice for her career?

“Sooner or later the girl has got to resent his indifference.”

What these people don’t seem to realize is that beneath her exterior of naivete and breathless bewilderment, Marilyn Monroe is one of the most sensible and naturally bright beauties in Hollywood.

She can hold her own with any sophisticated glamour star you care to mention. And she knows in her heart that Joe’s so-called indifference is not indifference at all. It is independence and self-reliance.

“It may be okay for other guys to manage their wives’ careers,” one of Joe’s friends says. “Sid Luft and Judy Garland, Marty Melcher and Doris Day, Freddie Brisson and Rosalind Russell, Tom Lewis and Loretta Young. But they’ve all got show business backgrounds.

“Joe’s background is baseball. Just because he was one of the greatest outfielders the game has ever known, he doesn’t feel entitled to call the shots on Marilyn’s career.

“The only time I’ve ever heard him give her any advice is when she and Twentieth were negotiating a contract. ‘The publicity is swell,’ he told Marilyn. ‘Only be sure to get the money.’ ”

As for Joe’s refusal to pose for pictures with Marilyn or to visit her on the set, he isn’t being contrary and he isn’t trying to be difficult. He’s just being himself.

But finally, toward the end of Show Business, the rumors of Joe’s indifference became so widespread that he decided to dispel them by visiting his wife on the set.

Quietly and unobtrusively, he showed up and stood in a corner while she sang her tempestuous heat wave number.

“I’m here,” he announced, “because the newspapers insist that there must be something wrong between Marilyn and me because I don’t visit her at work.”

When she finished her song, she ran over to him and said anxiously, “I hope you liked it, dear.”

“I liked it all right,” Joe said, “but it takes so long to shoot so little. It makes me nervous hanging around here watching everybody get ready.”

A moment later, DiMaggio posed for a picture with Irving Berlin and then as quietly as he had entered the studio, he drove out in his 1953 Cadillac.

“He never has liked parties or previews,” Marilyn says, “or show business celebrations. And before we were married, he never would take me to any. I didn’t expect marriage to change his habits or his likes and dislikes.”

So far as anyone knows, Joe has posed in the studio with Marilyn for only two shots. On each occasion there was a third person along.

One time Joe visited Marilyn on the set of Monkey Business, a film she made with Cary Grant. Joe agreed to stand up for a photo with Marilyn and Cary. After the negative was printed, Grant’s face was cropped out.

On another occasion Joe visited Marilyn with David March, the agent who had arranged their first date. This time March’s face was cropped out.

Joe has been offered large sums of money to pose with Marilyn at home.

“My private life is private,” he says, “and that’s out. Right now too many kids know where we live because the picture of the house we’re renting was published in the magazines. They ride up and down the street and even ring the front door bell.”

“As soon as our lease expires,” Marilyn says, “we’re moving. I don’t know where, but we’re moving.”

After ten months of marriage, Marilyn still insists, “Joe comes first.” But the studio has pre-empted most of her time.

Marilyn has said on many occasions that Joe has no objections to her continuing her career so long as she spends her evenings at home with him.

During the day Joe likes to play golf or go to the races or listen to the ball games. Marilyn has no interest in these.

Since sports, spectator or participation, are no fun for her, Joe figures that it’s best for Mrs. DiMaggio to do what keeps her happy. And Marilyn is happiest when she’s working in front of the cameras.

“Lots of times,” she recalls, “I starved so that I could have the chance to act in pictures. Joe sees no sense in my giving it up. Besides, what would I do? Act as his caddy on the golf course?”

In the studio Marilyn is surrounded by talented craftsman and artists whose appeal to her is primarily intellectual.

Natasha Lytess, who is probably Marilyn’s closest friend, is a great dramatics coach, one of the finest in the business.

Years ago when Marilyn was fired from Columbia, Natasha took the young girl into her apartment. In Marilyn she recognized a totally unprepared, uneducated but potentially acceptable actress.

So Natasha, the widow of an outstanding German novelist, introduced this young, lonely girl to the fascinating world of Shakespeare, Freud, and Thomas Wolfe. She taught her about the various schools of acting, about art and literature and life. In Marilyn she found a responsive mind.

Subsequently, writers who interviewed Marilyn, expecting to find her a dumb bunny, were startled when she spoke briefly but knowledgeably on George Bernard Shaw, the Stanislavsky method of acting and the works of Eugene O’Neill.

It is Natasha Lytess who is responsible for much of Marilyn’s acting success, and Marilyn is the first to acknowledge this. It is Natasha Lytess who still coaches Marilyn on every line. But once the day’s work is done at the studio, Marilyn closes the iron door. Intellectual stimulation is over for the day.

One does not find Natasha Lytess dining with Mr. and Mrs. Joe DiMaggio. Nor are the DiMaggios found at Hollywood Bowl listening to a symphony or at the Biltmore Theatre engrossed in a play.

Chances are they are watching a good, old-fashioned western on TV or perhaps visiting Joe’s friends, Vic and Marguerite Massi, or maybe entertaining Joe’s sister Marie and her daughter, down from San Francisco.

At these gatherings Marilyn does not expound on the virtues of Marlon Brando as an actor. She doesn’t talk about the excitement she felt when she watched Brando perform on the set of Desirée. Nor does she talk about the dance teaching of Jack Cole or studio politics.

By the same token, Joe does not discuss the various idiosyncrasies of Casey Stengel or Ted Williams’ batting average or the bases Jackie Robinson has stolen.

The DiMaggio family discussions are usually limited to immediate plans and problems: where to move, to buy or to build, the welfare of Joe’s relatives (since Marilyn has virtually no family and practically no close friends). By nature, neither Joe nor Marilyn is talkative. Nor do they crave excitement and wild times. They are a peaceful, very-much-in-love couple.

Marilyn did not marry for scintillating conversation, sparkling dialogue, or the furtherance of her career. She married purely for love, a family and a home.

“I never had these things as a child,” she says. “With Joe beside me I’m never alone any more.”

Loneliness is frequently a state of mind. When Marilyn was single there were hundreds of men in the motion picture industry intensely anxious to cultivate her friendship. But still, she was lonely because she felt in her mind that she belonged to no one. In case of illness to whom would she turn? In case of unemployment, who would lend a hand?

All of that is different, now. No matter how she fares in her career, Marilyn feels that she still has Joe, and this situation gives her more courage and independence and security than she’s ever known before.

It also helps her career immeasurably, since the studios rarely take advantage of a girl who has a financial alternative. Before she was married to Joe, Marilyn was suspended by her studio because she refused to make Pink Tights.

Marilyn’s salary at the time was $750 a week. The studio knew that she had saved practically no money, that sooner or later she would be hard up.

Once Marilyn got married, the situation changed completely. The girl had someone to support her. This called for new tactics. The studio signed Sheree North in an attempt to stampede Marilyn into Pink Tights, a script she had refused.

But Marilyn refused to be stampeded. She had Joe for a husband, and she didn’t care who the studio signed.

In the end, it was the studio that capitulated. Monroe was given a new contract, the lead in Show Business,and she was told to forget about Pink Tights.

This was her first triumph in studio negotiations, and Marilyn realizes that she won largely because she had a husband to back her up.

You can see therefore what Joe means to this girl, and why she is willing to live in two worlds on his terms.

When Marilyn is with Joe in San Francisco, there is no studio discussion whatever. She helps her sister-in-law Marie with the food, occasionally cooks spaghetti for Joe—he has taught her how—makes the rounds of the relatives, dines at the DiMaggio restaurant on Fisherman’s Wharf which is run by Joe’s brother Tom, and in short, she does everything to please her husband.

In most homes it’s the husband who goes off to work in the daytime and returns at night to the waiting arms of a loving wife. When Joe and Marilyn are living in Hollywood the setup is reversed. This doesn’t necessarily mean, as many detractors imply, that the marriage will founder. All it means is that Joe and Marilyn have developed a way of life that fits their own particular set of circumstances.

Right now their strong love is the bridge that spans Marilyn’s two worlds. Tomorrow it will be a baby, perhaps, and when the baby does come, Marilyn’s career will be relegated to third position behind Joe and bambino.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1954

No Comments