Fame Cloaks The Lonely Heart

The train pulled slowly into the station. It was a small town, quiet, unimportant. A few people got on, a few descended to the platform. The train paused several moments, then lumbered off. The town receded into the distance and the past.

During those few moments Kim Novak pressed her face eagerly to the window. She was watching the shabby railroad flats drift by; watching a man hawking newspapers; watching a little girl straddling a ragged picket fence and waving to the brakeman. She thought about the little girl, living in the commonplace railroad town. “I wonder if she’s happy here,” Kim murmured wistfully. And then she wished for the little girl a life as full and rich as her own: Happiness and all the things she ever wanted.

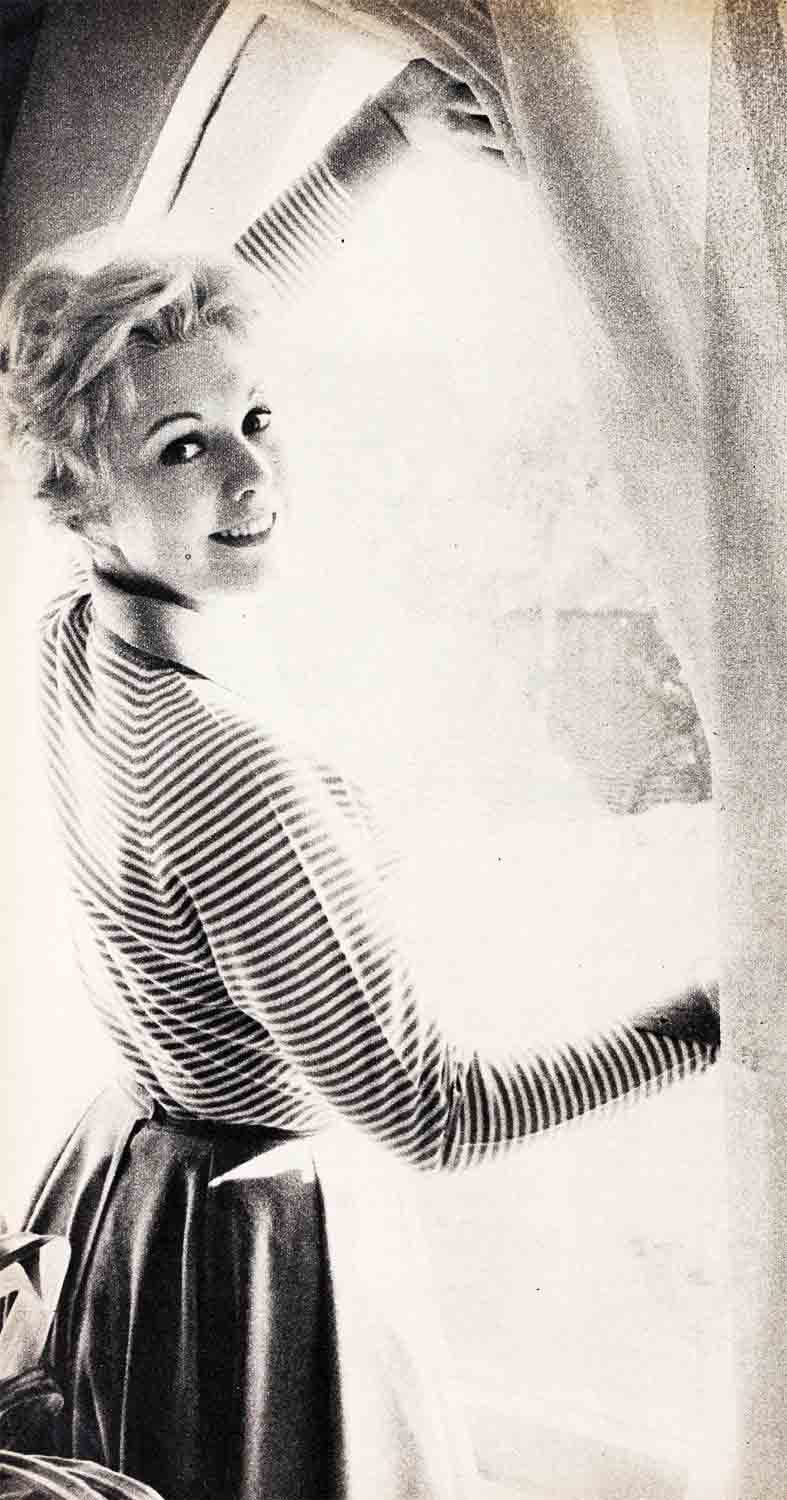

In Kim’s world of premieres and lovely dresses and handsome escorts, it may seem odd to wonder about a strange child living in a strange town. But Kim is different from most of us. Her imagination likes to wander—often into the far corners of other people’s lives. When she was a little girl on Chicago’s Sayre Street, she peopled it with make-believe inhabitants; endowed inanimate objects with souls and thoughts of their own. Shy, fearful of strangers, the real dramas of life did not touch her; only the drama of living within herself. She could pour out her heart to a rose or weep over the death of a leaf that fell from a tree. Perhaps that is why, today, she can give such sensitivity and warmth to a make-believe movie character, as she did in “Picnic” and “The Eddy Duchin Story.” Or why she can wonder so poignantly about a lonely little girl on a picket fence in a railroad town.

AUDIO BOOK

Little Marilyn Novak had wished for a gang to belong to. She’d wished to be popular. To be beautiful. To have a pretty dress, store-bought. To marry a prince. But most of all she had wished to belong, to be accepted by the crowd.

Although she could not then know it, her wishes were to come true on a staggering scale, far beyond anything she had ever envisioned or even could humanly fulfill. And in that lies the fateful irony.

Today Kim Novak is more popular than she can believe possible of herself—and privacy is a luxury she cannot afford. She is beautiful—and must slave to make the world forget or at least ignore it. She has glamorous clothes, yet she has neither the time nor even the desire to wear them. She has no time for anything that is frivolous or dilatory, that is not work or the preparing for work. Today she is caught up in a feverish drive to earn the fame that is already hers—and in that she has no time to live or to love.

Kim Novak’s star has risen far beyond the heights envisioned by the little dreamer of Say re Street. And Kim Novak is consumed with an unrelenting need for Kim, the actress, to catch up with Kim, the star.

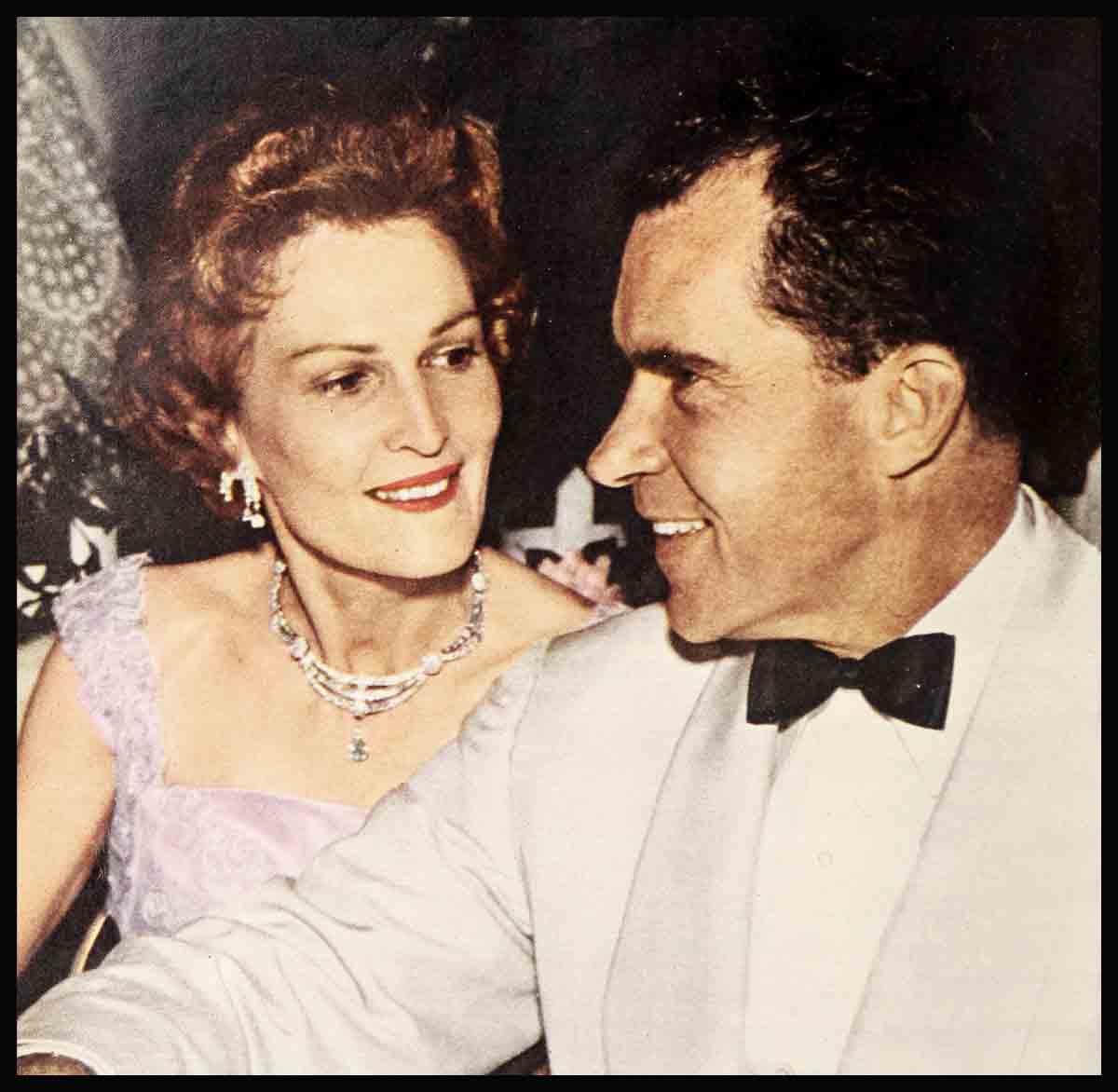

Phenomenally, with only six pictures behind her, Kim is starring in the “Jeanne Eagels” story, a difficult dramatic role coveted by every top actress in town. Immediately thereafter Miss Novak, who has never sung or danced professionally, is joining professionals Frank Sinatra and Rita Hayworth in “Pal Joey.” As a result, she is working too many hours a day, both on and off camera.

“It’s now or never,” Kim says. “Things won’t wait. I’m not bucking for anything. I’m just trying to do the best job I can.”

Perhaps the reason for this is that Kim still feels left out. In her own mind she does not belong to the group in which she now lives—the group of talented, able people, the real craftsmen of the movie industry. Desperately she is trying to be one of them. Others may be as well known as she, but they have more ability. “Someone else could just step into ‘Jeanne’ and do it right,” Kim says. “But I have to work. I have to catch up with my fame.”

Unfortunately, Kim is at a disadvantage. She didn’t start as one of the dedicated; movies fell into her lap without half trying. “I never starved to act,” she says. “I never painted scenery. This wasn’t a burning thing from childhood for me, as it has been for so many others. I didn’t fight for it. But today it’s in my blood, and I want it to stay.”

To Kim’s friends it seems as though the contest is an inner one—Kim against herself; Kim against her feelings of inferiority; Kim against her fears of never being good enough. They are afraid her standards are too high, that she expects too much. They have seen her become ill with fright and anxious with worry over a new role. Her friends are concerned, and rightly so. Kim is driving herself at an inhuman pace.

Mac Krim was one of the first to speak out. “Look, Kim,” he said, “your health comes first. The human body will only take so much.”

But Kim doesn’t listen. “I can’t help it,” she says. “I have to do this now. After ‘Jeanne Eagels’ I’ll take it easier.”

This is what she said after “Picnic.” This is what she said after “The Eddy Duchin Story.” Mac thinks that this is what she will say after “Pal Joey.”

What Kim seems to fear as much as not making the grade, despite all her hard work, is not being wanted by the public after a while. She is obsessed by a feeling of impermanence. It is actually a basic disbelief in her own popularity. People don’t really like her, she reasons; they just think they do—now. The fear wells up in her stronger when she imagines that at the height of her artistic achievement she will be box-office zero. All the work will have gone for nothing. It does no good to point out her fabulous success to date—how she was polled number-one box-office star by Box Office Magazine itself. Her first reaction was simply, “Ridiculous! It couldn’t be true!” Then, when she finally believed that it was true: “Do you realize, now all I can do is go down?”

Not, however, in the experienced opinion of producer-director George Sidney who’s directing Kim Novak in both “Jeanne Eagels” and “Pal Joey,” and foresees a long and sparkling future for her. “Like Jeanne Eagels, Kim Novak is a natural,” he says. “She has that golden thing you can’t give anybody if it isn’t there. Kim was born with the magic called talent.

“We wouldn’t have made the ‘Jeanne Eagels’ story without Kim,” Sidney says. No other actress was considered for the title role in the picture he describes as “the story of the rise and fail of a meteor who came out of nowhere and blazed across the sky too fast and broke into a thousand pieces. That was Jeanne Eagels.

“Kim is in essence very much like her. Kim has depth and with it the same kind of spirit, the freedom and abandon, the same latent ability that made Jeanne Eagels the great actress of the American theatre.”

But although “Eagels” is in the vernacular an “Oscar part,” Kim says she isn’t driving for an Academy Award. “I don’t believe in making goals. Then you’re just disappointed. But whatever I do, I give everything. That’s the way I am. I can’t understand anybody doing any job and not doing the best she can.”

Which is all too true, Kim’s friends say, of “Kim, the perfectionist.”

Mac Krim learned early in their acquaintarc? how determined Kim can be about any project. Mac plays polo and Kim, who’s mad about horses, would ride along and cool off the horses with him. One day she insisted on hitting a ball off a horse.

“Oh no you don’t,” he said.

“If you do it, I can,” Kim insisted. Whereupon she grabbed a helmet and a mallet and took off—right over the horse’s head.

“Kim took a nasty spill. She was bruised and shaken up, but she insisted on remounting immediately. Not many girls would do that. This I liked very much,” Mac recalls.

Ironically enough, it was the same determination—with another goal—that was to take Novak out of Mac Krim’s life so much of the time later on.

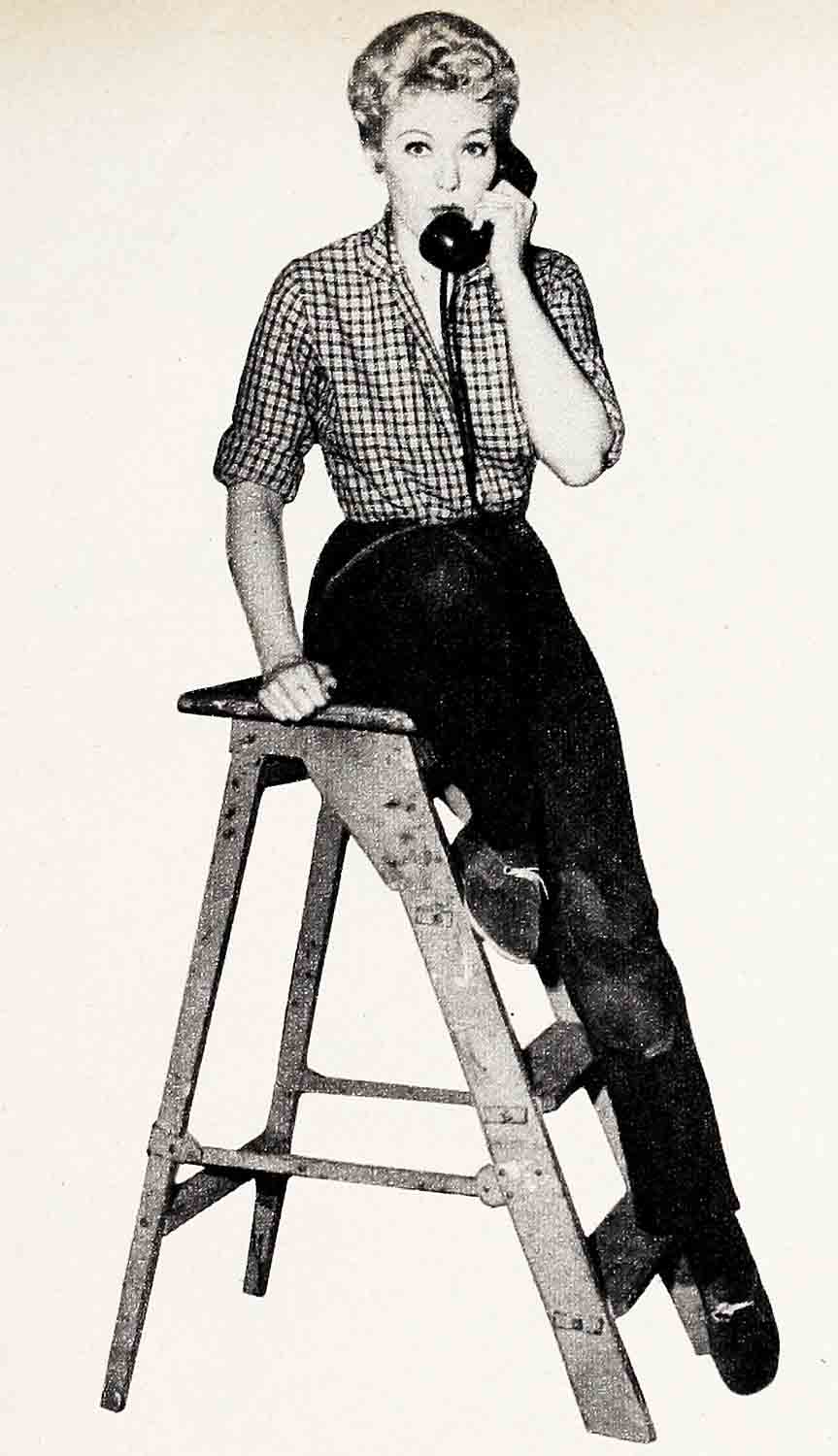

“Kim is so conscientious about her work—I can’t tell you. At dinner Kim’s studying her script. Riding along in the car, she’s reading her script. Before she started ‘Jeanne Eagels’ Kim was studying dancing for ‘Pal Joey’ four hours a day. When I picked her up at night, the kid would come limping out of the studio.”

“Take your shoes off,” Mac would say when Kim crawled wearily into the car. And as he recalls now, “She would have Band-Aids on her feet, and blisters. They would be bleeding.”

“Nobody works as hard as Kim,” agrees Norma Kasell, Kim’s secretary and her long-time Chicago friend, who first encouraged a shy, insecure teenager to take up the modeling that eventually brought her to Hollywood. “Kim would dance so long and so hard, she’d dance herself right out of her shoes and not even notice. Kim would stay with a step until she got it if it took all night. Kim loses herself completely in whatever she’s doing, and it has to be right—exactly right.”

Kim is a brutal critic of her own performances. In a projection room she will agonize over even a wrist movement that appears awkward to her. When a reviewer of one of her earlier pictures remarked that Kim essayed such-and-such role “and looked beautiful throughout,” Kim was in tears. “Who cares about looking beautiful throughout,” she said. For Kim, her beauty is just one more obstacle in proving she’s an actress.

When she isn’t working before the cameras, Kim takes drama lessons from Benno Schneider at the Columbia studio from ten a.m. until noon, dancing lessons all afternoon, singing lessons from seven to eight p.m. (or before ten a.m.). Two evenings weekly she spends four hours working with Batomi Schneider’s drama class. The other three evenings she usually rehearses for the class. Dinner? Often a hot cup of soup and a hamburger she picks up at Googie’s en route home to change clothes.

“If I fix something at the apartment, I relax and let down. This way I don’t lose my momentum,” explains Kim. “When I let down, I let down all the way. Then I can’t do anything more. I have to keep right on going now. It’s the drive that keeps you going.”

However, for all Kim’s “drive,” the physical hardships, long hours and loss of sleep almost caught up with her. The studio had been working against time from the beginning, to finish by the first of March in order to keep commitments with Frank Sinatra and Rita Hayworth for “Pal Joey.”

Costumed scantily as a hootchy-kootchy dancer in the carnival scenes, Kim worked during rain sequences and freezing nights. When a studio worker tried to put a coat around her between scenes, Kim said, “I’ve got to get used to this—without the coat—so I can go right into the scene.

“This one is exceptionally hard,” Kim continued. “I haven’t slept more than three hours a day since we started. After we get through working, I have to have my hair done, and with this elaborate hairdo, that sometimes takes four hours. By then it’s midnight if we are working days, and I’m due back at the studio by four or five a.m. We shoot Saturdays. And on Sundays I’m supposed to rehearse. We never have time to rehearse on the set.

“I came to work one afternoon at two-thirty and I didn’t finish until the next day.” At eleven the next morning Kim was driving across the ranch lot when another player hailed her with, “Just Corning to work?” She’d never been home.

“I don’t intend to do this from here on,” Kim said earnestly, meaning every word at the time. “At first I’ve had to work hard to make up for lost time. But I’ll let down after this one. Not during this,” she said quickly. This was “Jeanne Eagels”—Jeanne too worked this way.

Kim feels a double responsibility in playing the part of the famous actress whose name is legend in the theatre today. As she told a friend, “I have got to do it right—I’m Jeanne Eagels.”

Kim has dedicated herself to this portrayal, yet part of her is the sentimental girl from Sayre Street, Chicago, who feels she may be missing something, the part who says, “For three years now I’ve been working on the day of my birthday. We worked New Year’s Eve and I went home and fell asleep at nine p.m. On Christmas afternoon I had to come in and get my hair done and rehearse some dialogue changes. This is a little too much . . .”

Then as usual come Kim’s famous last words, “But after this one—I’ll let down.”

During this one, Kim’s dressing-room walls are taped with clippings of Jeanne as Sadie Thompson in “Rain.” She has talked to everybody who ever knew Jeanne Eagels on the West Coast. She has had long sessions with her understudy, whom she found still living here. Together with Norma Kasell, Kim has combed every library for material about Jeanne. They had amassed two scrapbooks full. “I’ve read every line ever written about Jeanne. You have to do this to know the person, to become the person,” says Kim.

From the beginning Kim’s chief anxiety concerned the latter tragic sequences when the famed actress had resorted to alcohol and dope. Driving along Wilshire Boulevard with Mac Krim one night, Kim had said suddenly, “How will I do the alcoholic bit? You can’t act a part unless you’ve lived it.” Then she startled him, saying seriously, “Mac—you’ll just have to get me intoxicated some night.” Although it would never materialize, it would have been a double performance—neither of them drink.

Determined to stay in character emotionally, particularly in this challenging characterization, Kim told him conscientiously that she wouldn’t be seeing too much of him during the picture. Particularly during the latter sequences. “I’ll be horrible then. I don’t want you to see me that way.”

But during this happier time of the story, Kim Novak was bubbling along, typically keying her own mood to that of the character she’s portraying.

Kim admittedly lives emotionally within that person as much as possible. And she would have little interest in Kim Novak for the time being. “I’m living Jeanne Eagels’ life now and I think that’s enough. I’m not Kim Novak at the moment. And what interests Kim Novak doesn’t interest me,” she says frankly.

“But we have much in common,” Kim goes on. “Jeanne was mercurial and sensitive, and with me everything changes too. My moods, my attitudes, the way I feel towards people—everything.”

With Kim’s wealth of imagination and emotion she sometimes gets so deeply within the character she’s portraying, it’s difficult for her to pull out—even if she would. During the filming of a dreamy death-mood sequence in “The Duchin Story,” Kim terrified a friend one night with her strange expressions and behavior. “What’s wrong with you?” her friend said.

“Oh—please forgive me,” Kim said. “I can’t get out of the Duchin bit.”

Kim can’t understand how more experienced stars can turn emotions off and on at will. To her close friends Kim explained when she went into “Jeanne Eagels” she wouldn’t be seeing too much of them. “I’ve got to stay in character,” she said. “I can’t be Kim Novak at night and be Jeanne Eagels the next morning.”

And a lovely serious-faced Kim was saying now, “I believe you keep a part of all the people you portray. Sometimes I think I’ve left Kim Novak somewhere along the way.”

Not too far away. Not too far from the shy little girl named Marilyn who wrote poetry and lived within the vivid world of her own imagination peopled with lucky clowns and governed by a magic wishing tree. A little girl who used to recite her stories so graphically the teacher would protest to her mother, “Marilyn’s imagination is inflaming the other children. Unless she stops, I’m not going to call on her.”

This imaginative child did not have her roots in an exciting stage or screen background but in a quiet old-world family.

Kim’s father, Joseph Novak, a former history teacher, later became a freight dispatcher for a railroad. She had a wonderful practical down-to-earth mother. And Marilyn’s beloved Grandmother Kral was an immigrant from Prague, Czechoslovakia, who handed down to this little girl her own reverence for a worn black rosary.

Not too far from this background is Kim, the girl who worries when today’s star-pressures close in so fast there’s no breather to share life with those who mean much to her. As one who is close to her says, “Kim feels badly because there’s so little time to be with all the friends she used to see. She worries. Will they understand?”

Not too fast, or too far, is the meteor that is carrying Kim Novak into fame’s clouds today to bring her back to earth, rescued by her own substantial earthy heritage.

Kim is grateful for her early life. “I don’t regret those years. They add to my happiness today,” she says. “Because of them I can appreciate today even more. We never went without food. We always had the necessities—just no luxuries. And today it’s a big thrill to be able to afford a few.”

In spite of long hours and the wearying demands and the fierce pressures, today is a big thrill for Kim Novak. To all who consign her to a vale of tears as a “melancholy blonde,” a “bewildered beauty” and the like, she says, ‘I’m not unhappy. I’m working with emotion all the time. I’ve always been quick to laugh and cry. When things unhappy happen—and in this business they always seem to be happening—I cry. I’m not good at shrugging it off when something goes wrong. I show how I feel. But when it’s out and over, I don’t go around brooding or boiling under the surface as many others do.

“There are all kinds of happiness. And I’ve had all kinds. But I’ve never had the work kind, and this is what I want now. Perhaps people think I’m unhappy because I don’t do things that spell happiness to them. I’ve done all that. In college I belonged to a sorority and I went to dances. I’ve gone out a lot since, and I’m not through. I’m still going to live it up like crazy.

“But today, my work is my happiness. Believe me, if I were to get dressed up in party clothes—which I hate doing—and go to large parties, this would make me very unhappy. I don’t like being out with crowds of people. I have to be with a lot of people all the time in my work. I’ve taken a little cottage down at the beach now and that’s for me. Just give me a script to read and an open fire and I’m happy—

“And when I’m happy—nobody could be happier,” laughs Kim. “Last week I was so happy,” she recalls typically. “it was a beautiful day. I went swimming in the ocean—the picture was going great.

‘I’m a moody and impulsive person and I go along with whatever I feel like doing at the time. Right now I want to work. This is work? A love scene with Jeff Chandler?” she says laughingly. Then she answers her own question about motion pictures. “This is work—but it’s my happiness now. The only kind of happiness I haven’t had is being married,” says Kim. “But that will come.”

Jeanne Eagels was happy too this day. “During this carnival sequence with Jeff she’s at the very peak of her happiness,” Kim says of Jeanne. “It’s the happiest day of her life—but she doesn’t know it. After this—no more.”

And suddenly her two worlds are one.

“Maybe it’s the same thing with me,” says Kim. “It may be when Mac and I were playing miniature golf last year and riding bicycles on Wilshire Boulevard. Right then may have been the happiest days of my life. Someday I may look back and know this. But today—you don’t know.”

Today there isn’t time to know. “I’m a one-way girl,” Kim says in her own honest way. “This would be a very bad time for any man to be interested in me.”

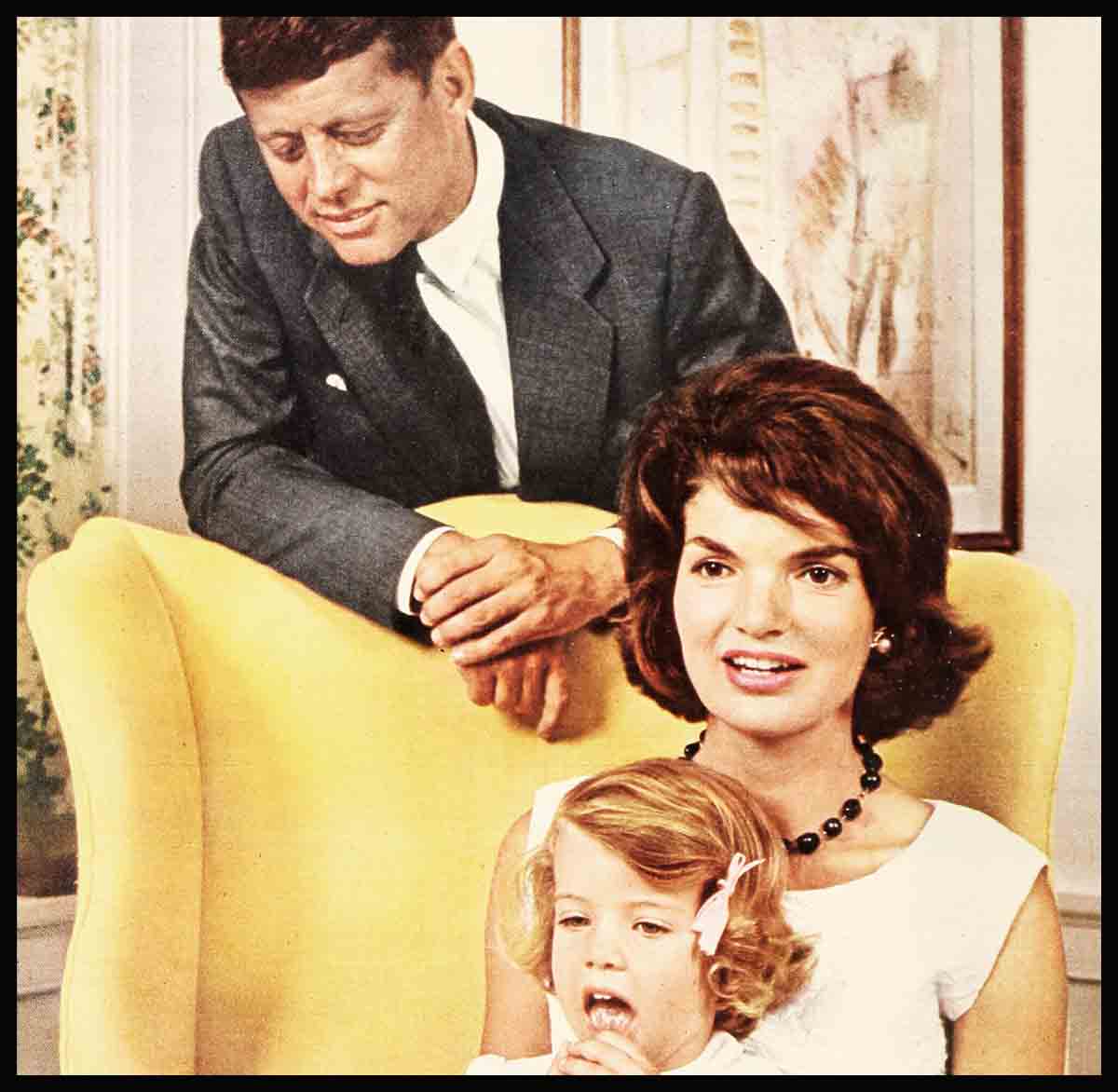

Gossip columns linking Kim with any number of various swains are a source of mystery to her. She’s dated Sinatra briefly, but there have been only two men presently in Kim Novak’s life, each important in his own way. Mac Krim, Bel Air sportsman and investment broker, of whom Kim says, “He’s just a wonderful guy.” And Count Mario Bandini, wealthy young Italian businessman, who was an exciting beau during Kim Novak’s whole European adventure, when she attended the Cannes Film Festival last year.

Kim met the charming, intelligent Bandini at a luncheon in Rome. Although columnists keep referring to him as a Count, he told Kim that he was not a Count—that over there they just referred to him that way. Their first date was to go to a palace ball, with dreamy-eyed Kim in white swirling chiffon, surrounded by dignitaries and titles on every side.

Mario Bandini was a devoted, intelligent, charming escort, joining Kim and her publicity representative, Muriel Roberts, in Venice, Cannes, Paris—wherever they were, whenever his business interests allowed. He’s associated with romantic memories of Maxim’s and Harry’s Bar and lilacs and Venetian gondolas and Neo-politan songs.

“Count Bandini—they’ve even got me doing it—Mario’s coming in April,” Kim informs us. “He was coming Christmas but I was working and he postponed his visit. He’s a fine person, nice-looking, gallant, just the way you think a European man would be. Just the kind of man I wanted to meet when I knew I was going over there.”

Kim will make no predictions about what will happen. Personally, she leaves her future to any prophets who dare. But it’s doubtful whether Mario Bandini, or any European, would compete with—or understand—the world that is Kim Novak’s now.

This world nobody could understand perhaps as well as Mac Krim, who knew Marilyn Novak when Fame tapped her for a chosen child. He helped give her confidence during those first months when she needed it most. He understands Kim’s dedication to a goal, to proving her place in that world. And watching Kim’s star rise he must know that world could someday be without him.

Once, back in Chicago, a little girl had wished for a prince—but there’s no time and no place for one in the kingdom into which Kim has been projected so rapidly. She’s a one-way star in a one-way sky. And how do you stop a meteor in its flight?

But there are times when the two worlds of Kim Novak meet and are one.

Kim Novak was Jeanne Eagels Christmas Eve. But when the cameras stopped rolling and the sound stage darkened, and Hollywood put all its magic away, a weary Kim told Mac Krim, “I want to go where it feels like Christmas, where there are children. Do you want to go with me?”

They were soon in the car heading for Rolling Hills, where Norma Kasell lives with her husband and three children. Kenra, nine; “Little” Kim, six; and Kristin, aged two. “Big Kim” idolizes “Little Kim,” who’s quite a personality in his own right. Blond crew-cut, all-boy, and a wide grin. “You came first—I was named for you—” Kim tells a delighted little boy.

“We’re having quite a few people over,” Norma Kasell had explained on the phone to Kim. Old friends from Chicago. Two couples, one with four redheaded little boys. Still want to come?”

“Oh yes,” Kim said. They sure wanted to come.

It was a real folksy evening. Neighbors dropped by and the house bulged with old-fashioned family cheer. They sang, they taped everything anybody could think of to say, and they were having so much fun making Christmas for the children that all present decided to spend the night there.

For a small house—this took some spacing. The children were bedded down on the floor, and the adults spent most of the rest of the night wrapping presents for them. Kim finally got sleepy and went to bed in a single bed in one of the rooms, Little Kim blissfully asleep on a pallet on the floor beside her bed.

Around dawn a Chicago father decided to look in on all his redheads and make sure they were tucked in. “I can only find three of my boys!” he said. His five-year-old was nowhere around. The search was on. They found him sleeping on the shoulder of a beautiful blonde. He’d climbed into bed with Big Kim. And Jeanne Eagels was nowhere around.

This is the Kim Novak who wished upon a tree and got magic beyond measure. The lonely girl who longed to be part of the crowd and who today belongs to millions.

The Kim who won’t draw the blinds of her bedroom because the dawn is “so crispy new—the most beautiful time of the day.”

The Kim who rides on the back of the wind. Who loves to lie on the beach at night and count the stars in God’s heaven—and forget her own.

THE END

DON’T MISS: Kim Novak in Columbia’s “Jeanne Eagels” and “Pal Joey.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK

zoritoler imol

25 Nisan 2023Its like you read my thoughts! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the guide in it or something. I feel that you just can do with a few percent to force the message house a bit, but other than that, that is great blog. A great read. I will definitely be back.

vorbelutrioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023I truly enjoy looking through on this site, it contains superb posts.