Death Drive—James Dean

The last story about Jimmy

One morning a few weeks ago, I got a phone call from a well-known agent, who also happens to be a personal friend of mine. “Dave,” he said, “I am holding in my hand right now a story about Jimmy Dean that’s gonna . . .”

“Forget it, Phil,” I said quickly. “There aren’t going to be any more Dean stories in MODERN SCREEN.”

“But this story, Dave, it . . .”

“Look, Phil,” I said, “come September 30th Jimmy will have been dead two years. Why don’t we all just let him rest in peace? Furthermore, all of his close friends have already said everything important there is to be said about Jimmy. They loved him. They’ll never forget him. That’s it.”

“This isn’t written by any close friend of Jimmy’s. It’s by his mechanic, Rolf Wütherich. He is the only person in the whole world who was actually with Jimmy when it happened. Rolf was right there on the seat beside him. Well, he’s out of the hospital at last, and . . .”

“You mean this guy Rolf was in the actual crash?”

“That’s what I mean, Dave.”

“Well how did it really happen? I mean, what’s he say? I’d like to know that and so would our readers.”

“Meet me for lunch,” Phil said, “and I’ll let you read the story. Then you’ll know what really happened on Jimmy’s last ride.”

So Phil and I met for lunch. I didn’t say much to him—I was too busy reading the story. I left my sandwich untouched on the plate and my coffee got cold. When I was finished, Phil said, “What do you think?”

For a moment I had trouble focusing on his face. I was still inside the world of the story, still with Jimmy on that last tragic day. Then I said, “I’ll buy it, of course. And Phil, I’ve never thanked you for bringing me a story before. But . . . thank you.”

That’s how I came to buy another story about Jimmy Dean. It is probably the last big story that we will ever print on Jimmy. It begins on the next page . . .

EDITOR

In memorium—this second year since Jimmy Dean’s death—MODERN SCREEN prints this story by the man who was with him at the end . . .

When Dean, on September 30, 1955, raced to his death in his Porsche car, he was not alone. His mechanic, Rolf Wütherich, was in the seat beside him. Miraculously, Wütherich survived. He had to spend many months in the hospital. Here, for the first time, he tells the story of what really happened on that fateful day when his friend Jimmy Dean was killed . . .

I don’t think I shall ever forget that day in September, two years ago. That was the day I rode with Jimmy Dean to his death.

I was a service mechanic for Porsche cars, and I was a very busy man indeed—film stars like fast cars, and I was experienced as a racing car mechanic in major European motor races.

That’s how it happened that I was James Dean’s last passenger, on that awful day when he rode to his death.

When I first met Jimmy Dean, he owned a Porsche Speedster, a somewhat smaller sportscar than the Porsche Spyder he crashed in. The Speedster had carried him to victory at Bakersfield, Santa Barbara and other races. It was at one of these races that I first met Jimmy. I was looking over the Porsche cars—that was my big job as a mechanic—and Jimmy and I got to talking.

I had seen him driving in another race—he hadn’t been racing long, but he was a good driver: he had that essential feel for fast cars and dangerous reads. He had that sixth sense a racing driver can’t do without. We talked about his car for a couple of minutes, and then he took off—for a win.

Two weeks later, I was walking along Hollywood Boulevard when I saw Jimmy Dean coming toward me. This particular sunny afternoon opened the last chapter in the life of this boy whom millions loved—and still love. . . .

He was walking with that slow gait of his, a toy monkey on a rubber band hanging from his wrist, hopping up and down with each movement of Jimmy’s arm. Jimmy was in a completely carefree, happy mood. We shook hands, and we talked about—sports cars, what else? Jimmy wanted to enter the big-car class in his next race—the class for cars with the large, powerful engines. That was Jimmy’s big dream. And he told me about the big Bristol car he had ordered.

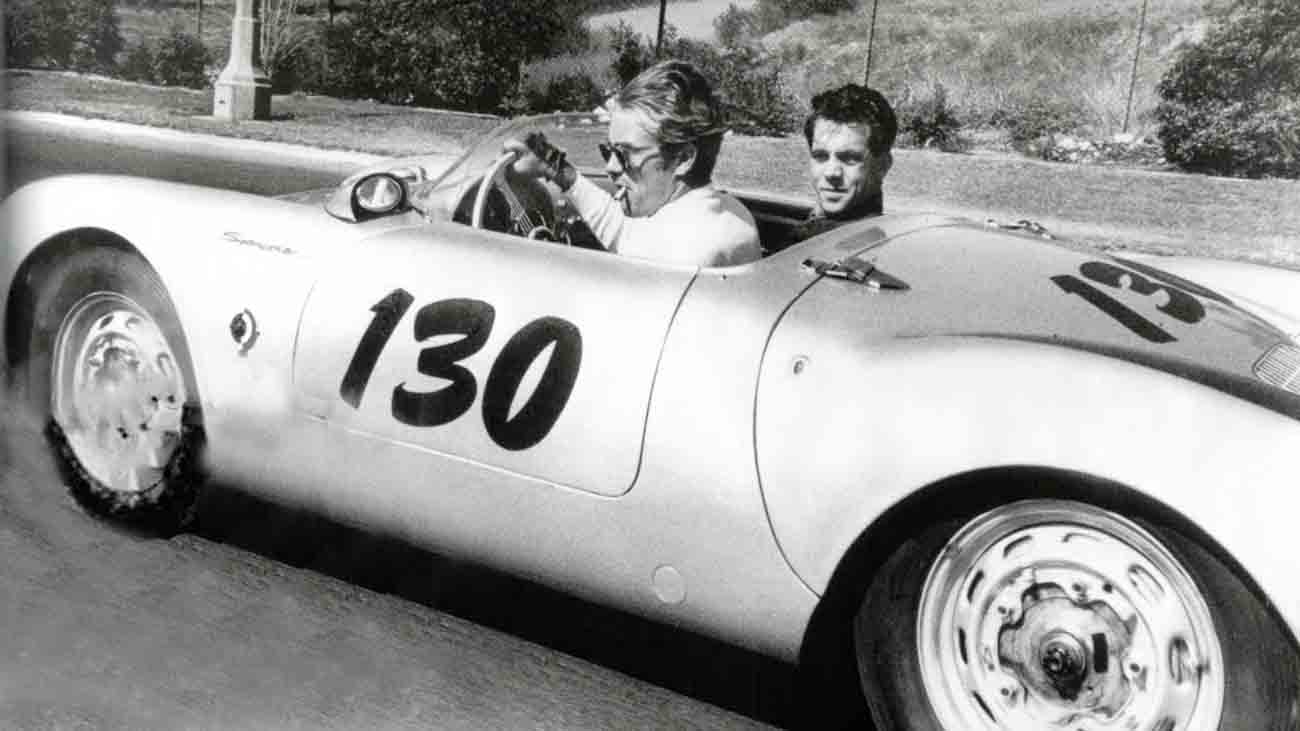

That was when I remembered about the Porsche Spyder we had on sale. I told Jimmy about this car—told him how powerful it was and that it might be just what he wanted to make his dream come true. Next day Jimmy was at the shop to look it over. It was September 19, 1955. He drove it once around the block. And really liked it. He made one condition before buying the car—he made me promise that I would personally check it before each and every race he took part in, and that I was to ride with him to all the races. Naturally, I said yes because I couldn’t think of anything I’d like better.

The last ride . . .

The filming of Giant was scheduled to end that same week. Jimmy’s contract didn’t allow him to enter car races during the shooting of a picture, so Jimmy wasn’t free to drive in a race till the following “weekend—the fateful weekend of October 1, 1955. He was going to take part in an airstrip race, about three hundred miles from Los Angeles. But time was running short, and before entering such a race a driver should really get acquainted with his car. The Spyder should have been driven by Jimmy for at least five hundred miles. That’s why Jimmy told me, “We won’t take the car by trailer to Salinas. We’ll drive there. You come along, and on the way you can check things.” We met that Friday morning of October 1st, in my workshop at COMPETITION MOTORS. It was only eight in the morning when I went to work checking Dean’s Spyder—the motor, oil pressure, ignition, spark plugs, tires— and all the rest of it. Jimmy paced the floor. Once he thought I was taking too long and he came over and tried to help me. I said “No thanks. You’ll only complicate things!” He walked away, with that grin of his, and thumbed through a But several times he came back and asked a thousand questions which I had to answer very exactly and in great detail. When the Spyder was all ready I fixed a safety belt for Jimmy on the driver’s seat. I didn’t fix one for the passenger’s seat: Jimmy would be alone in the car during the race. He sat in the car and tried the safety belt.

It was just before ten a.m. when Jimmy’s friends, film extra Bill Hickman and photographer Sandy Roth, showed up. They were to go with us to Salinas in Jimmy’s station wagon, a 1955 Ford. Jimmy’s father and his uncle Charles Nolan walked in and Jimmy drove his uncle around the block a couple of times. Charles put his arm around Jimmy’s shoulder and said jokingly, “Be careful, Jim. You’re sitting on a bomb!”

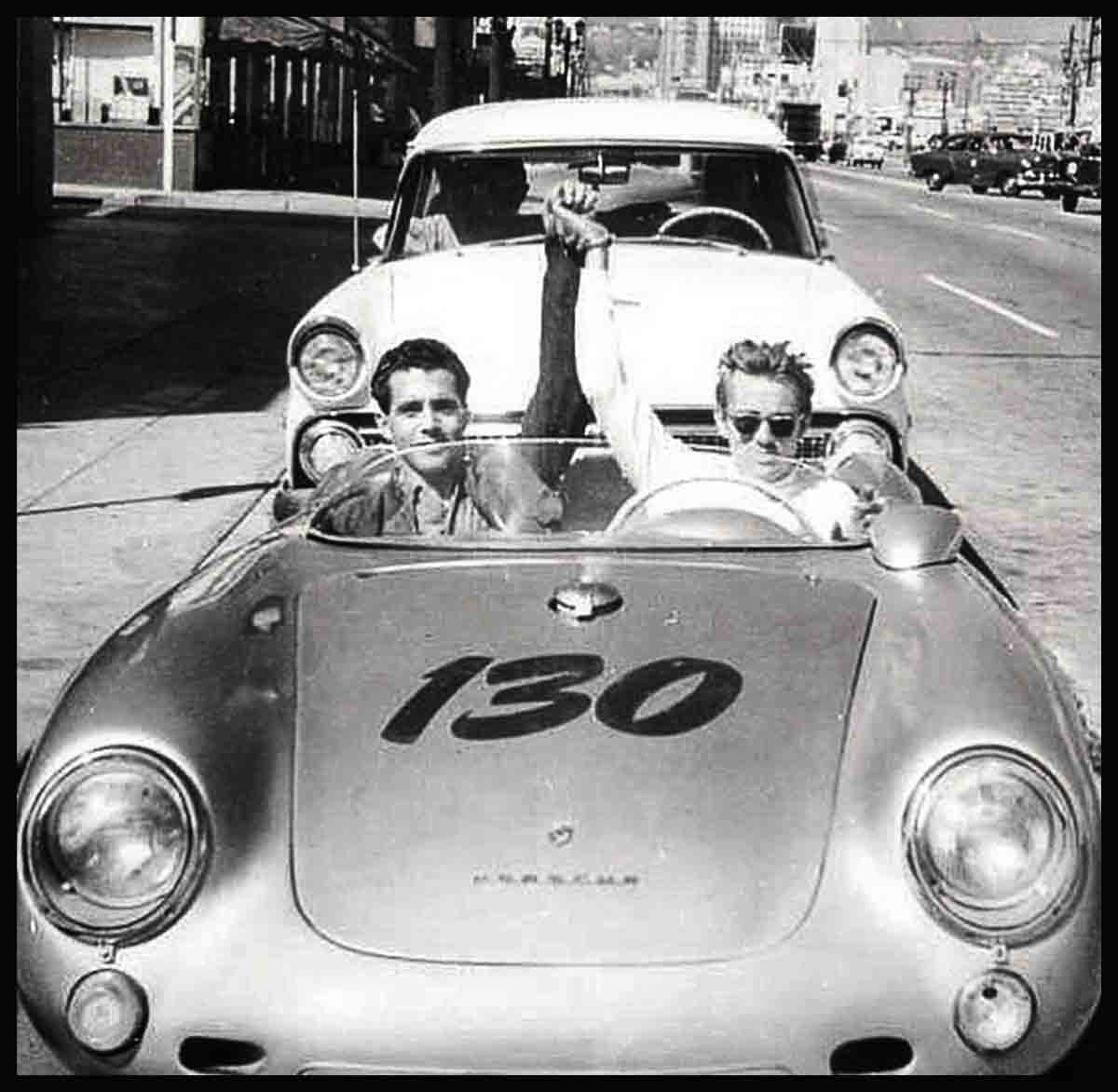

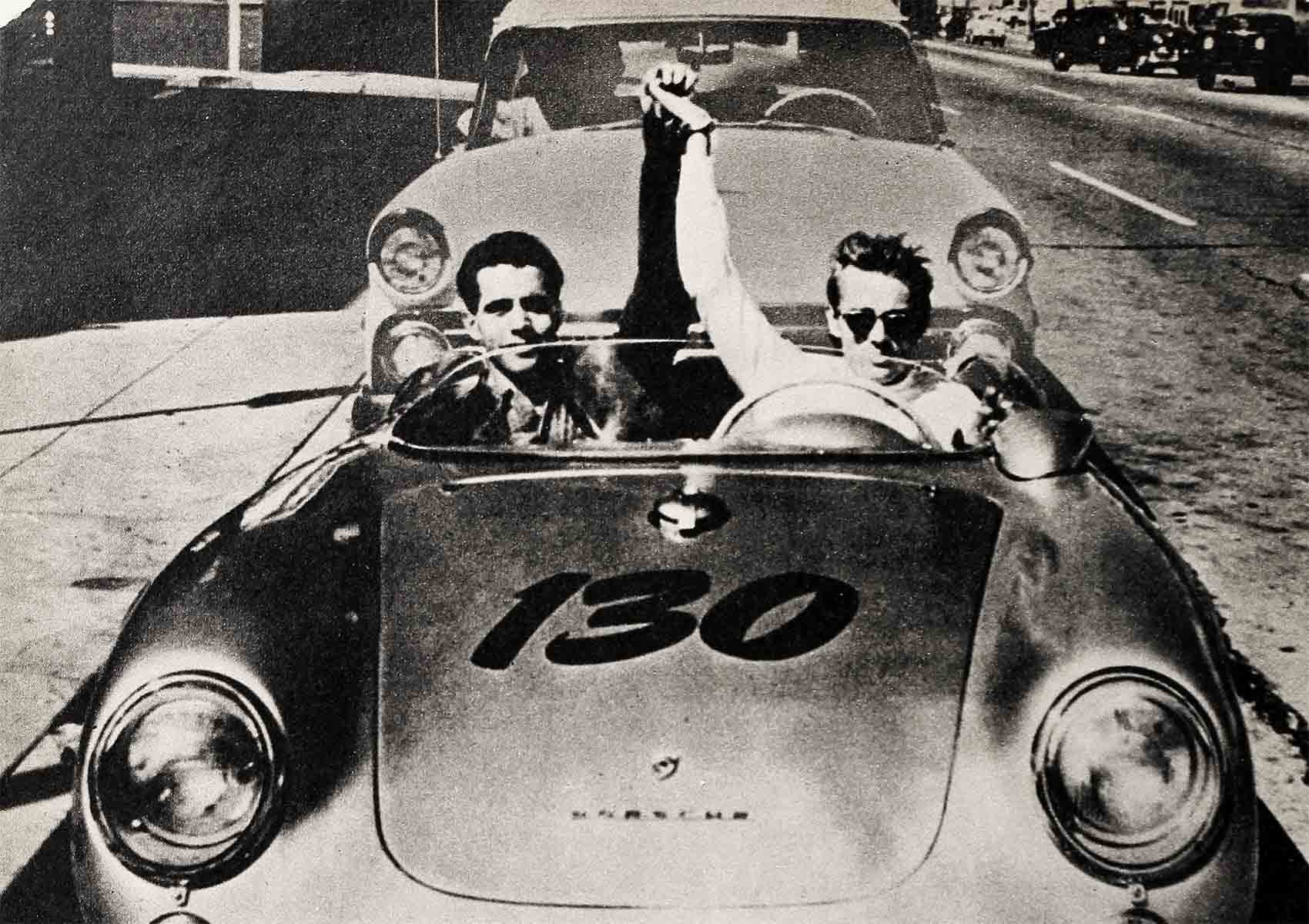

Around noon we were ready. Jimmy wearing light blue trousers and a white T shirt, threw his red jacket behind the seat in the car and fixed sun lenses to his glasses. At one-thirty we said goodbye to his friends, his father and his uncle, and I sat down beside Jimmy in the Spyder as Jimmy took the wheel. Someone took a last snap of us. Jimmy gripped my hand and pulled it up in some kind of salute. This was the very last picture that was ever taken of James Dean. The last picture of him . . . alive.

Traffic was very heavy at this time of day. We went out to Ventura Boulevard, filled up the gas tank and reached Highway 99, which cuts through the mountains between Los Angeles and Bakersfield. Sometimes we were leading, sometimes the station car with Bill Hickman and Sandy Roth took the lead. The sun was high in the sky. I listened to the sound of the Porsche’s motor—and it was purring. Jimmy kept nudging me again and again. “What’s the rev number?” “How’s the oil temp?” “You sure this is the right road?”

A warning to Jimmy

Jimmy Dean was very happy. We whistled and sang, cracked jokes, and Jimmy laughed loudest at his own jokes—in that way of his. We smoked one cigarette after the other, and I lit them for Jimmy, hunching low under the windscreen as the. wind tore along—almost taking the glowing tip of the cigarette away with it. Jimmy was in high spirits, and we felt like we had been very close friends for a long time. The setting was ideal—a very fast car on a sunny day with a long stretch of road ahead of us.

A few minutes before three we stopped at a roadside snack-bar. Jimmy ordered a glass of milk for himself and would not rest until I had an ice cream soda. I began to feel uneasy about the race—felt as though maybe I’d better warn Jimmy—“Don’t go too fast!” I said, my face dead serious. “Don’t try to win! The Spyder is something quite different from the Speedster. Don’t drive to win; drive to get experience!” “Okay, Rolf,” he said with a smile, a sort of smile that laughed at me and my fears for him.

A gift of friendship from Jimmy

“Give me the signs when I’m going over the rounds!” he said. Then he hesitated for a moment. He pulled a ring from his finger. It wasn’t an expensive ring—just some little souvenir he had picked up, but I knew he had a sentimental attachment to the ring. He handed it to me.

“Why?” I asked.

“I want to give you something,” he said. “To show we’re friends, Rolf.” I was touched. The ring just fitted on my small finger. My hand was much bigger than Jimmy’s.

After a while Jimmy’s two friends arrived in the station wagon. “Don’t let him drive too fast,” they said half jokingly, half serious, as Jimmy climbed behind the steering wheel again.

A few minutes later, there was a police car chasing us. They stopped us and handed Jimmy a summons—he was over the speed limit of fifty miles per hour. The police handed another summons to the driver of the station wagon. The funny thing was that Officer O. V. Hunter seemed to be much more interested in the gray Porsche than in his summons, and Jimmy answered all his questions as if they were two drivers gabbing over a cup of coffee. Before we took off again, Jimmy told his friends, “We’ll wait for you at Paso Robles. We’ll have dinner there.” Paso Robles was about a hundred and fifty miles along the road.

“Non stop to Paso Robles”

It was late afternoon. The road was one gray line cutting through a monotonous landscape—here and there a very slight bend, otherwise straight ahead. It felt like driving on an endless ruler. The only break in the monotony was at Blackwells Corners—a service station with a small store attached to it, in the middle of nowhere. When we reached Blackwells Corners a sleek, grey Mercedes was parked in front of the store, another of the racing cars on the road to Salinas. Jimmy stepped on the brake and we got out of the car. He took a close look at the Mercedes and chatted with the owner, Lance Reventlow, the twenty-one-year-old son of Barbara Hutton, until the station wagon caught up with us again. “How do you like the Spyder now?” Jimmy’s friends asked him.

The driver of the other car was a young student named Donald Turnupseed. When Donald found out that he was responsible for the crash, he broke down in tears. “I didn’t see him; my God, I didn’t see him,” he wept. Donald himself suffered almost no injuries.

Rolf Wütherich left the hospital on crutches. Three months later, he underwent a bone grafting operation, connecting his hip bones with an eight-inch silver mail and screws.

The ring Jimmy gave Rolf at Ridge Route was torn from Rolf’s finger when he was thrown out of the car. He still has a scar where the ring was. This ring—Jimmy’s gift of friendship to him—lies buried somewhere in the desert where Jimmy died. . . .

THE END

—BY ROLF WÜTHERICH

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957