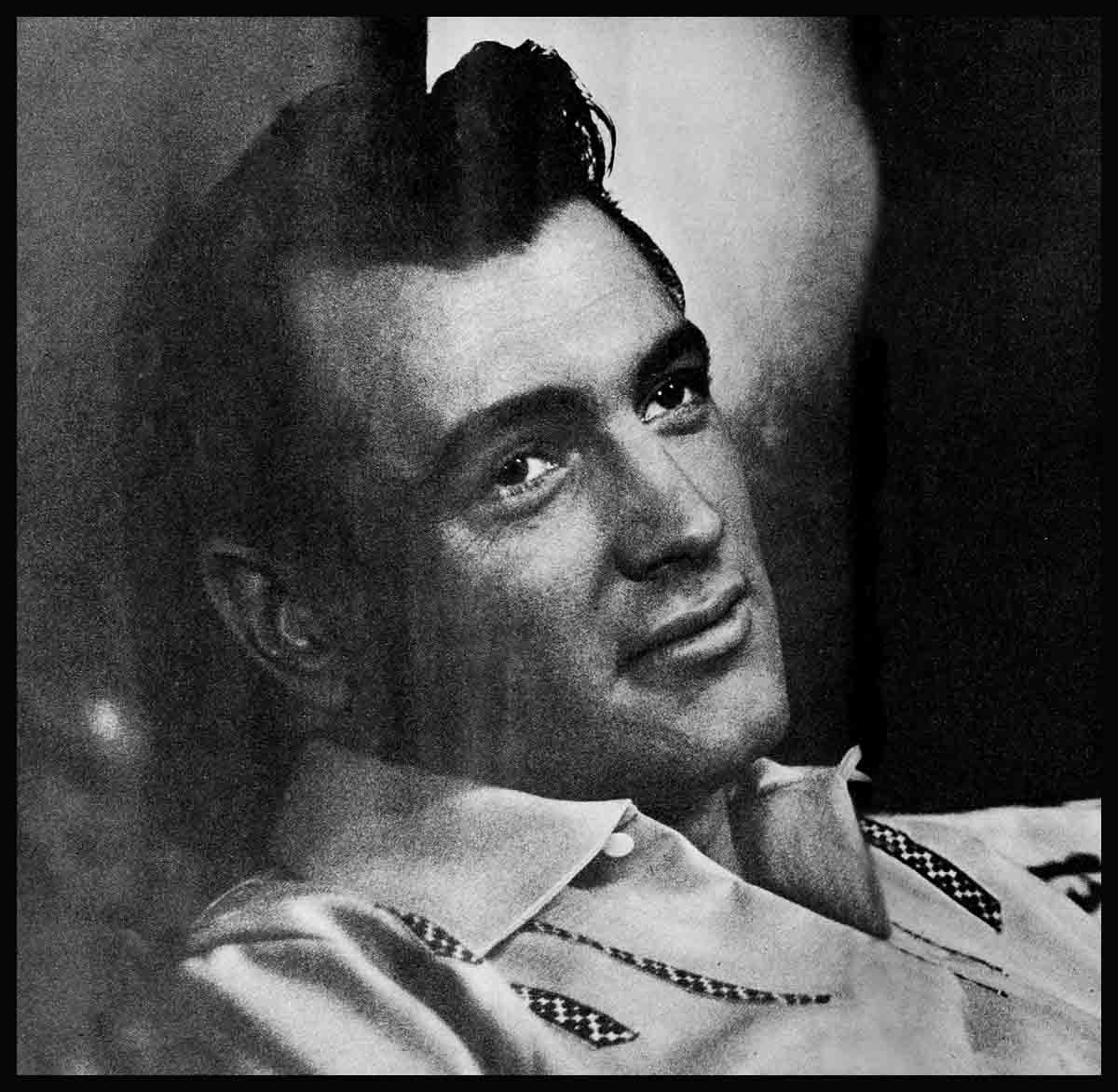

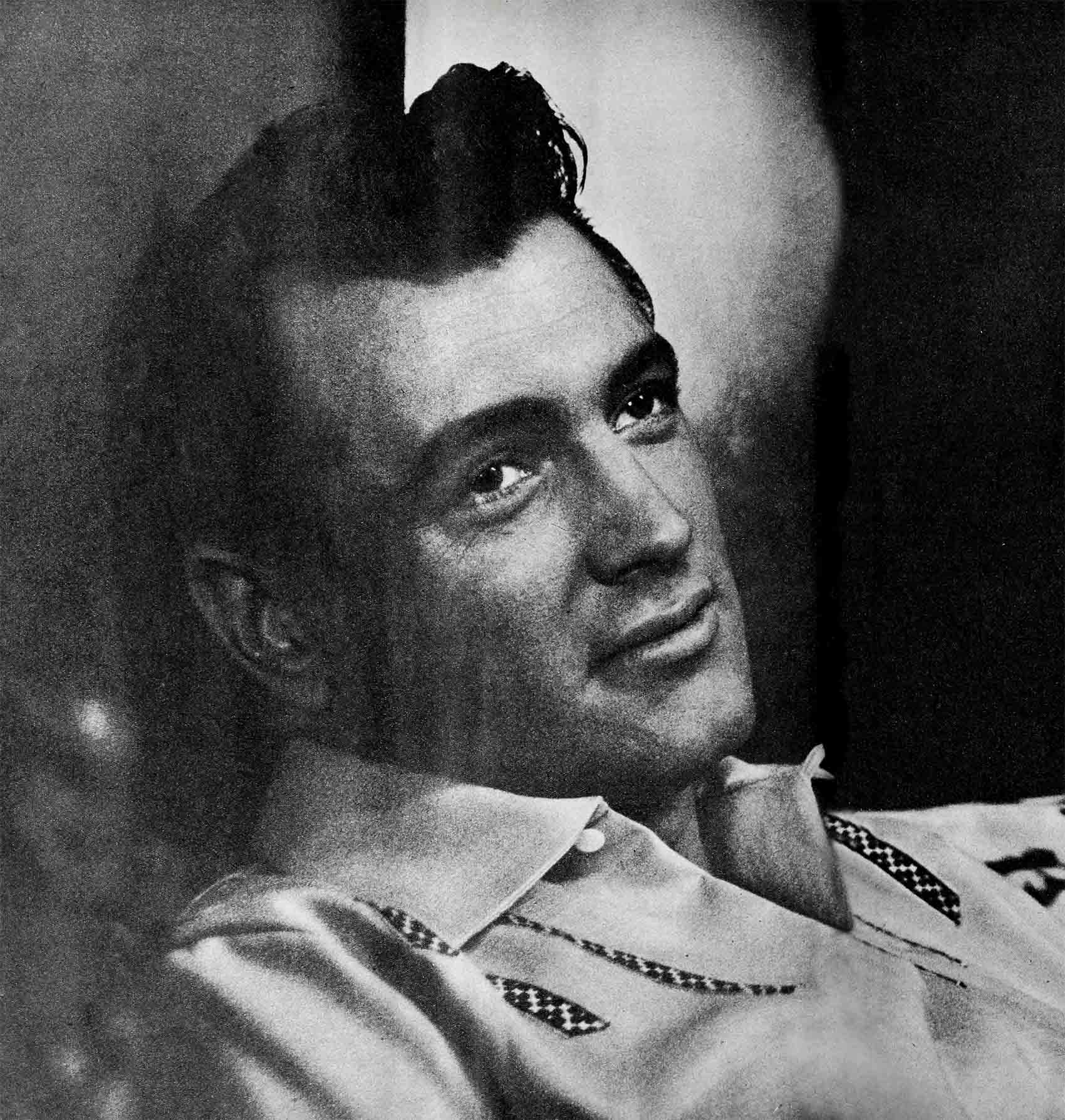

A Long Way From Home—Rock Hudson

Rock Hudson turned the key to the lock of his hotel room door and quietly let himself in. Walking over to the telephone he lifted the receiver and asked, “Is the dining room still open?” At the answering “Si, signore,” he ordered his dinner, reflecting for a moment on how much he would have preferred a thick broiled steak and a heaping helping of mashed potatoes this evening. “Ah well,” he sighed, “When in Italy do as the Romans do.” And this was close to Rome.

He replaced the phone in its cradle and the familiar leaden sensation he’d come to know as loneliness overtook him. It was funny, he thought, how long Phyllis and he had looked forward to this trip to Italy for his role in “A Farewell to Arms.” They’d listed the museums and art galleries they’d walk through “till their legs would ache,” planned gay side trips to Naples, Sorrento and Capri, and anticipated the glorious weekends they’d be spending together, always together; but things hadn’t worked out that way at all.

They’d traveled as far as New York when Phyllis had become ill. “Must be something I ate, no doubt,” joked Phyllis before she’d visited a doctor and Rock’s concern had changed to alarm when he’d diagnosed it as hepatitis and sent Phyllis to a hospital. The rest of it was a blur of Rock’s leaving for Italy alone, and daily wires and letters and telephone calls, first to a hospital in New York, and then to another in California. There was the shock of the cablegram telling him that Phyllis needed an operation, and the comfort of that phone call to California with Phyllis assuring him that surgery had been minor, that it had been successful, and that she was going to be all right.

He’d stopped spending his week-ends hunting for a villa for them to share, and had thrown himself into his work, welcoming the almost daily script changes that kept him on the set till 8 o’clock every evening. But the hour or two of silence when he’d return to his hotel rooms in the evening were the worst part of the day. Then his loneliness and his longing for Phyllis became so acute that he could taste it, touch it, feel it.

Slowly, he walked over to his portable typewriter on a desk in a corner of the room and inserted a fresh piece of stationery. “Dear Phyll,” he started pecking out on the typewriter keys. And suddenly, he wasn’t lonely any more.

In the years before his marriage, Rock had seen a lot of rooms. There were the rooms of the small apartment he’d come home to from school—quiet, empty, lonely, while his mother was at work. There were the rooming house rooms when he’d arrived, friendless, in Hollywood. They should have been a refuge in the strange, new, busy town. But they weren’t. There were the hotel rooms on the personal appearance tours, the ones he’d ambled back to when the rest of the gang had said goodnight. Large rooms, small rooms. square rooms, oblong rooms, some with cracks in the ceiling that you could count. But in one respect they were all alike. They were lonely. And so, for a while, se the house he’d finally been able to buy.

He’d always wanted a home of his own. Yet he found that furniture, a stack of books, and a hi fi set didn’t make a home. He’d come in from the studio, toss his tie on a doorknob, rummage around in the icebox and have a solitary meal on whatever he found. He’d turn on the hi fi, sprawl in the overstuffed chair, thumb through a script, have a one-sided conversation with his dog. Then, invariably, he’d get up, climb into his car and take off. No place in particular. He never seemed to know where he was going, what he was looking for. After a while and many miles, he’d go home again. Home? Well, back to the dark, empty house.

And then, everything changed.

He’d always shuddered at the way they put it down in books. The light in the window, the little woman at the door, the roast in the oven, dinner by candlelight, the kiss as you stepped through the door. Somehow, writing to Phyllis, it was easier to express it. “Darling . . . this is what happened today.” And in those six words, you managed to sum up a marriage pretty neatly. Someone to talk to. Understanding. Someone to share things with, so you might never be lonely again. Only, somehow, letters weren’t as good as the real thing. They made you miss a person more.

Very often now he’d disappear early and the click of typewriter keys could be heard coming from his room. Some days, he’d walk away from a take and vanish into his dressing room. Photographer Bob Willoughby found him there one day. Willoughby wanted to get some pictures, wanted Rock to take a walk around the village. “If they don’t call me again before I finish this letter,” Rock agreed, and bent his head to the small, portable typewriter he carries.

“Writing to your business manager?” asked Willoughby.

“Nope,” said Rock.

Willoughby began to focus his camera and fish for caption material. “To your agent?” he inquired.

“To my wife,” said Rock. “And it should have gone yesterday.”

The following day was Sunday and more still pictures were scheduled. This time Willoughby met Rock at his apartment. When he walked in, he found a familiar scene. Rock at desk. “Same letter?” said Willoughby.

“Same person,” said Rock. “But this is today’s letter.”

There was a lot to write about . . . from Rome, from the locations, Misurina and Udine. There was the key gag. She’d get a kick out of that one. When he’d arrived in Rome from the states and climbed off the plane, Al Hix and the production manager had been there to meet him. “Somebody told me to give you this key,” said the production man.

He gave him the key and he and Hix stood there while Rock began to roar. They were, to put it mildly, puzzled. So he told them about the time he and Jack Diamond, head of Universal-International’s publicity department, had gone away on a publicity tour. Rock was continually losing the keys to his hotel rooms. It got to a point that, whenever Rock put his keys down, Diamond would pick them up. He soon had quite a collection of keys, and material for a running gag. Rock would go into a hotel in Milwaukee and ask for his key, the one he hadn’t had a chance to lose. The clerk would hand him a key from the hotel in Chicago.

Months later, in the airliner en route to Italy, the stewardess walked up to passenger Hudson. “Someone asked me to give you this,” she said, handing him a key. It was the first of a series, as he soon found out. So he wrote about it to Phyllis.

When she failed to mention it in her next letter, he figured that possibly she hadn’t thought it so funny after all. Fora while it puzzled him. Then one night, Al Hix walked up and handed him a key. This one looked familiar. Rock looked at Al. “Why this is the key to our front door.”

“Brought you a note, too,” said Hix, producing same.

Rock tore open the envelope and read the words on the card. “Don’t ever lose this key. Phyllis.”

Rock was a devoted, though long distance, husband. When the nurses left, and Phyllis was on her own, he sent a cable to Demi, their dog. . . . “Take good care of Mother. Father.” Then he sent one to Phyllis and signed it Demi. After that, he called.

“As for our publicity work,” publicity man Hix will tell you, “the picture layouts were like none I’d ever been on. The cameraman took pictures of Rock and Rock took movies of the scenery to send home to Phyllis!”

Rock did his job. But as another, less sentimental member of the company put it (After prefacing his remarks with, “Mention my name and I’ll track you down and strangle you.”): “Rock was worried. Plenty worried. He was itching to fly right back to Los Angeles. If he’d gone, the company would have been in one terrible spot. That Phyllis is all right. Both she and the doctor were on the phone, telling him to stay. But he was ready to go. The guy was dying to go.”

The crew member clammed up for a moment, Hudson-style. “The phone calls helped,” he finally said. “When we were on location in the villages, it was hard to get calls through, so Rock had one placed all the time. Sometimes he talked to her twice a day. When the call would come, somebody would hustle down to the set in a jeep or on a bicycle and get him.”

Members of the crew who had never met Phyllis came to know her. Sometimes because of the things he’d say. Often because of the things he didn’t say. In the villages, after work, there was no place to go, nothing to do. So the men in the company would get together and talk. And the conversation would turn, as such conversations do, to their wives. Joe (a very fictitious name) would discuss his wife’s tendency to nag. Sam (for obvious reasons, an equally fictitious name) might fondly growl about how his wife was a living shrew. They’d turn to Rock. “Hudson, haven’t you any complaints about Phyllis? You’re thousands of miles away, fellow. Now’s the time to get them off your mind,” they’d say, faces straight.

Hudson would grin. Once somebody piped, “Rock, the trouble with you is that you haven’t been married long enough. Or maybe it’s that you haven’t been married often enough. No wife is perfect.”

The Hudson grin broadened. “Mine comes pretty close.”

After a while, you could feel their attitudes change. Some of the members of the crew started coming in to Rock with suggestions. Sam asked, “Say, did you ever stop your car at the top of the hill just off the main road? What a view! I bet Phyllis would like it.” Rock thanked the man, drove out there and happily started to snap away.

Another time, Joe came up to him and queried: “Phyllis like sweaters? I found a nice shop in town.” Phyllis would indeed like sweaters, and Rock chose three beautiful hand-knits to send home.

And there was the teasing, too. One payday when everyone went off in a hurry to change their checks into lire, one of the cameramen on the picture stopped Rock to say, “Boy, maybe you ought not to cash your check. Maybe you ought to just convert it to stamps.” Good naturedly, Rock grinned. “What about the phone calls?” he asked. “Would you pay for them?”

The cameraman winced. “Mister, I’ve already got a mortgage.”

As the picture started drawing to its conclusion, Rock started counting the days. Soon, the letters and the conversations and the kidding about his letters would be over.

Soon, if Phyllis completely recovered from her hepatitis, she would join him for a holiday in Majorca and they’d make up for the fun they’d missed. And after that, there’d be Hollywood again, the place where he drove up a winding road every night to a modest little hilltop cottage. Inside it, a girl with dark hair and laughing eyes waited. He could reach her by turning a lock with a golden key. It was a key he’d never lose.

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957

gralion torile

11 Ağustos 2023I’m still learning from you, as I’m trying to reach my goals. I absolutely enjoy reading all that is posted on your blog.Keep the information coming. I liked it!