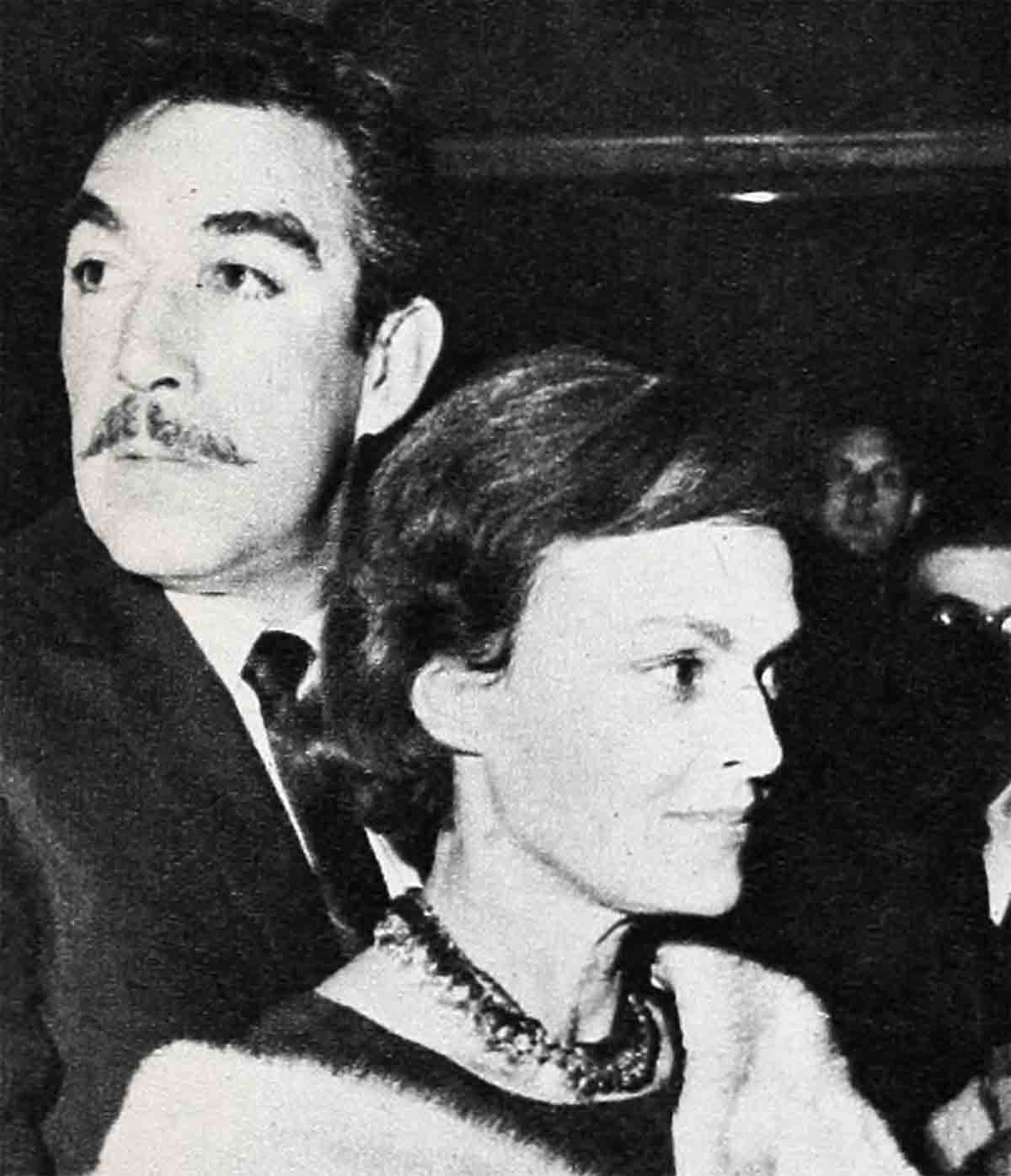

Anthony Quinn’s Love Child

This is less a story than a portrait. A portrait of a sinner. A portrait of one who has brought shame and suffering upon his wife and children, of one who has violated the precepts of religion and ethics, and one who stands accused before the world that watches him.

And, yet, of one who, in a time of testing, a time of trial, has found his finest hour. It is a portrait of a man. Of Anthony Quinn.

On the fourteenth of June, 1963, Anthony Quinn publicly admitted that he had fathered an illegitimate child, a son born to an Italian woman he met while working abroad—away from his wife—for more than a year.

“The child is mine,” Anthony Quinn said. “I can not deny him. I want him to bear my name and to be one of the heirs to whatever estate I have. It will be difficult for my four other children to accept. My wife has been deeply hurt. But my responsibility is to my new son.”

He said it and then was silent. He made no excuses, offered no sign of remorse. And the world, presented with the cold, sad facts, did what the world has always done—it judged the deed.

It is natural, of course, that the world should do so. The religious heritage, the moral standards of mankind are in the keeping of society—which is simply another way of saying in the keeping of all of us.

But for any one of us to judge truly it is not enough to know the facts—we must understand the man.

“You should judge a man,” Quinn once said, “by what he wants to give to the world and to life. You should judge him in his own culture and on his own level.”

This, then, is a portrait of Anthony Quinn. A portrait in his own culture and on his own level.

He was born in poverty and in danger. His birthplace was Chihuahua, Mexico; the year was 1915, a time of turmoil and revolution. His father was Frank Quinn, half Irish, half Mexican, a fighter with the revolutionary army of Pancho Villa. His mother, Manuella Oazaca Quinn, daughter of an ancient Aztec family, rightly feared for her life and her son’s. When Anthony was not yet two months old. She strapped him on her back and walked five hundred miles across Mexico to the American border. In this country she supported herself and her baby by the only means open to a Mexican woman—picking fruit and berries, following the harvest from place to place. Anthony was several years old before his father joined them.

(In Paris, where Quinn met the press, a reporter asked why he felt compelled to acknowledge a child another man might have denied. “I grew up without a father for the first few years,” Quinn replied, “and I know what complexes grow from it. I don’t want this child to have to go to a psychiatrist because he wasn’t wanted.”)

When Anthony was twelve his father died. The boy left school to wash dishes, dig ditches and work in a mattress factory to support his family.

The future stretched bleakly before him. He was poor and without education. Already he dreamed of becoming an actor, but he had nothing with which to implement his dream. He was not handsome; his eyebrows were bushy, his nose crooked, his mouth too small. A defect in the structure of his tongue gave him a speech impediment that only an expensive operation could remedy. He was painfully aware of local prejudice against Mexicans; even his Irish name did not save him from insult and abuse. The world was not a kindly place for Anthony Quinn.

Wants to want child

(“I want this child of mine to feel loved, and wanted,” he said in Paris. “I don’t want him to grow up feeling a sense of rejection.”)

When Quinn was seventeen, he talked a surgeon into performing the necessary tongue operation on credit. And he undertook his own education, reading voraciously, haunting museums and theaters. At twenty-one he became an actor, playing a Cheyenne Indian in “The Plainsman.”

In the quarter-century that followed, Quinn appeared in nearly one-hundred movies, more than any other major star. He became an “actor’s actor”—equally convincing as an Indian, a Mexican, an Eskimo, a Greek guerrilla, a cowboy, a hunchback, a king, a punchdrunk fighter and a circus strongman. He won a pair of Academy Awards—for “Viva Zapata” and for “Lust for Life” (in which he gave a brief but unforgettable portrayal of Artist Paul Gauguin. Accepting that Oscar. Quinn told the members of the Academy: “Acting has never been a matter of competition to me. I am only competing with myself. Thank you for giving me a victory over myself.”

In his chosen work, Anthony Quinn never took the easy way. On the set of “The Plainsman” he met the adopted daughter of Cecil B. DeMille.

Three weeks after meeting Katherine DeMille, he married her. Now on the Paramount lot lie could have had any role he demanded. All he had to do was ask.

A man’s honor

And so lie did what lie had to do. He walked away.

Turning down the offer of a $150-a-week contract, more money than he had ever seen, he left Paramount. He did not, he said, care to be known as the boss’s son-in-law. He preferred a long hard struggle. to lie won or lost on his own.

“What matters to me is a man’s honor, his responsibility to himself and to society. and the respect that is due his dignity,” Quinn said.

Tony and Katherine had been married four years when their only child died, accidentally drowned in a pond. Anthony Quinn took the tragedy badly. His life seemed for a time to stop. His friends said they wouldn’t have been surprised if he had refused to have more children, he had been hurt so deeply.

But he and Katherine had four more children, and he told each one of them: “Don’t ever play it safe. If you do, you’ll miss all that’s due you in life.”

Life could hurt Anthony Quinn. It could mold him. But it could not destroy him.

Out of poverty and ugliness and tragedy, a strong, brave, proud man had emerged—a man of passion, a man of impulse. A moment’s whim could carry him away; a sudden desire had to be satisfied, and satisfied that minute. Perhaps he remembered how death had snatched away his father and his firstborn child; perhaps he thought that if he failed to achieve his heart’s desire at once, at the very moment of longing, time would suddenly run out.

Caught up in the excitement of a poker game, he once bet everything he and Katherine owned—their car, their bank account, their house. He lost it all.

Years later, he suddenly decided to sell the house he and Katherine had virtually built themselves, to pack up the whole family and move to Italy. Before the impulse faded, a buyer was found and the sale consummated. But a few weeks later, passing the house one night, he was overwhelmed with a flood of memories: every tree, every wall seemed precious.

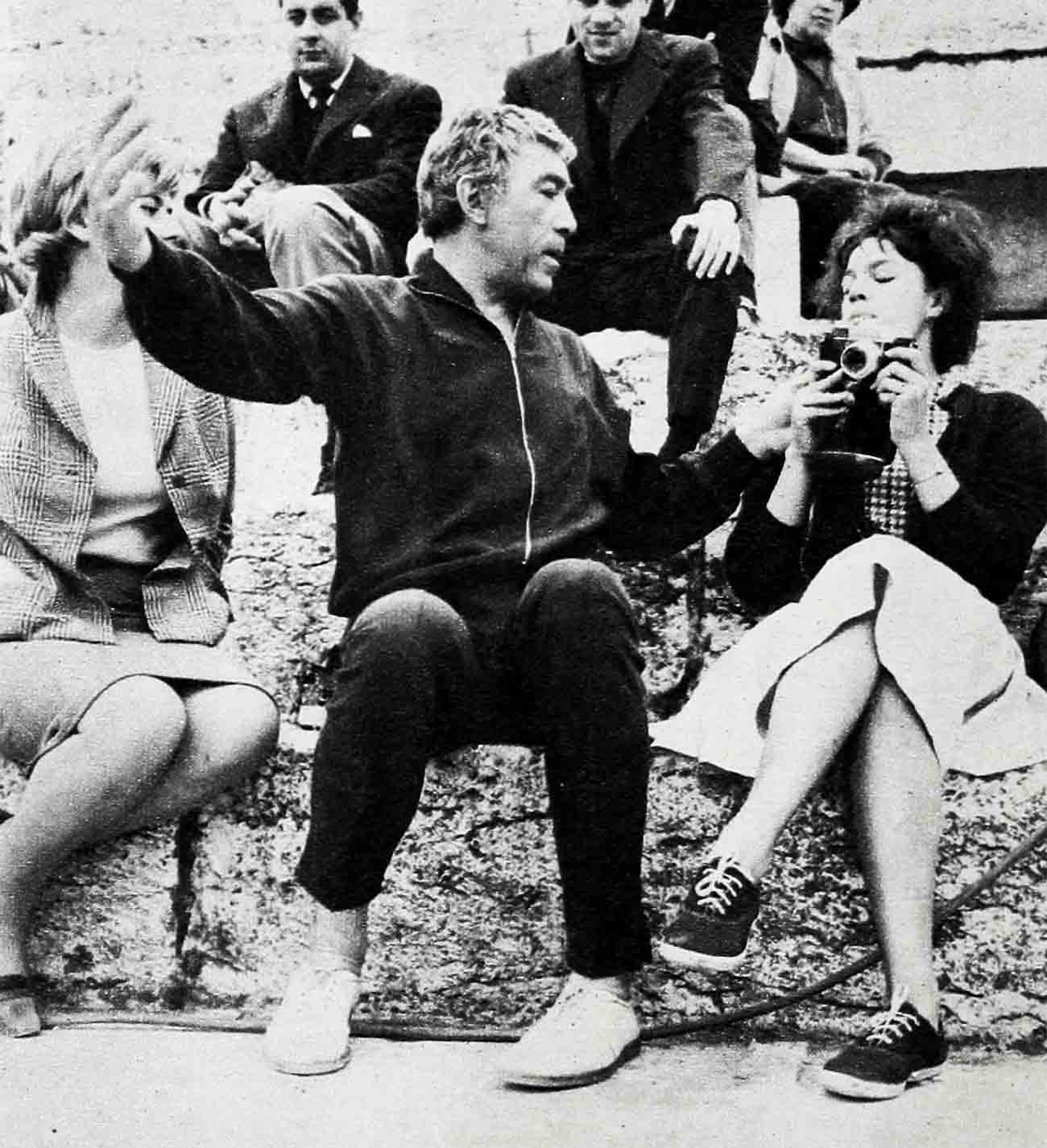

Later still, in Italy, he was stopped on the street by an excited man clutching a dog-eared manuscript. The man had a proposition: would Quinn act in a movie for no salary, playing opposite an unknown actress, in a story about a half-mad waif and a sadistic man? He would be paid for his services if the picture were a success. When the preposterous suggestion was made, Anthony Quinn was a major star with two Oscars to his credit. His time was worth money. But on impulse, he said yes. The man was now-famous Director Federico Fellini. The film was “La Strada.”

A man of impulse? Yes. A man too quick to plunge, too passionate to pause? Yes. But something more.

Anthony Quinn never considered shirking the price of his follies; he paid for what he had done and never whined at the cost.

He faced his poker losses by month after month of backbreaking work until he had earned back every cent he had gambled away.

He cheerfully, joyously paid $4,000 more than he had received for his home to buy it hack again, and considered the money well-spent.

He was able to look back on “La Strada” as one of the great accomplishments of his life, and to think of the pitiful sum he finally received from it as more than adequate reward for his work.

As good as you’re bad

Anthony Quinn once said: “You can only be as good as you dare to be bad.”

In March of 1963, in Italy, a baby was born. He was baptized Francesco Daniele. The infant’s mother was Jolanda Addolori, a twenty-eight-year-old blond woman from a noble Venetian family. The infant’s father was Anthony Quinn, and he was faced with the supreme test of his convictions.

He could, as so many men in his un- happy position have done, deny the child and its mother. He could—as many movie stars have done—pay heavily in cash to support his child in return for a guarantee of secrecy. In the eyes of the world, the child would have had no name, no father. It would be, like millions of illegitimate children, anonymous and lost. And Anthony Quinn would never have had to face an accusing world.

All he had to do was trade his child’s hope for his own safety.

He chose instead to face the world, to inflict the unwelcome, necessary pain on his family and himself—and by so doing, to save his son.

“When it comes to important things in life,” Anthony Quinn has said, “I consider myself a kind man. I really do not care what anybody else thinks—I try to find the truth and live by it.”

The truth was that the child was his own flesh and blood, and that Anthony Quinn could not find it in his heart to deny him. “Everyone,” he said, “will simply have to understand.”

This, then, is Anthony Quinn’s portrait. If he has repented, he has not said so; if he wants forgiveness, he has not asked for it. But this is a portrait of a man who can stand tall before the world, knowing that at the moment of truth, he chose the only way he honestly could.

“I have done a lot of looking and thinking in my time,” said Anthony Quinn once. “I think I have something to say. When I do, I hope I have the guts to be honest.”

This, above all, is the portrait of an honest man.

—THE END

See Anthony in “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Behold A Pale Horse,” for Columbia.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1963

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023Hi this is kind of of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding expertise so I wanted to get advice from someone with experience. Any help would be enormously appreciated!