You Haven’t Heard The Half About James Dean!

James Dean and I sat in his plush white Porsche, sipping a Coke at Hamburger Hamlet on the Sunset Strip. We’d just finished a long hard day on the set of “Rebel Without a Cause” and were in that delightful state of silence that only comes when the air is slightly tangy, the company really companionable and you’ve had a terrific day at the studio.

“Hi, Jimmy,” said a man who appeared to be a little older than either of us. Jimmy flushed slightly and said apologetically, “I’m sorry, I don’t think I know your name.” It was not only an apology to the man but to me, too.

The man gave Jimmy his name, and I could tell by the expression on Jimmy’s face that: this recalled nothing and with very good reason—he’d never met him before. Jimmy listened politely as the man explained he’d been sitting in the drive-in when we arrived and couldn’t help hoping that a fellow actor, who’d succeeded, would give him a few tips on how to get his foot in a studio door.

With that quick sympathy Jimmy has for a person trying, they were soon off comparing notes. I sat and listened and, as I did, I grinned all over. I thought, What a whale of a lot of things people don’t know about James Dean.

Jimmy, an oddball? Jimmy, sullen?

The first time we met was while Jimmy was making “East of Eden” and I was working on an adjoining sound stage where he had several pals. We were introduced when he came over for a visit. He was nicely dressed in well-pressed slacks and a sport shirt, was polite and intelligently interesting. There was nothing strange about him.

Six months later, in an old abandoned theatre in Los Angeles, the two of us were working on a television script that was to be my first grown-up role. I had been cast opposite James Dean and, like everyone else in Hollywood, I had heard the stories. I was, frankly, afraid of him. During the morning absolutely nothing out of the ordinary happened. The two of us worked, took our breaks when the director called them and finally lunchtime rolled around.

It had been a long time since I’d walked in this particular neighborhood, so I made my way through the crowds, hoping I’d see a little restaurant. There was no roaring motorcycle with brakes screeching to a stop to announce the fact that James Dean was following me. He simply caught up to me and asked, “Mind sharing lunch?” We found a cafe and, like actors, gabbed about the script we were working on and the show. During the four days we worked together, I brought my portable radio, tuned to the classical music Jimmy likes, and he brought hamburgers—which I like.

“Eden” made Jimmy Dean into a juvenile delinquent. I shudder to think what “Rebel Without a Cause” is going to do. In one terrific scene Jimmy, carried away by rage, knocks his father down the steps into the living room and almost kills him. Poor Jim Bachus—who plays his dad—really thought he was going to finish him.

In “Rebel,” both Jimmy and I play disturbed teenagers who go wrong from lack of sympathetic understanding and turn to each other for comfort. But there’s no sense diagnosing Dean a delinquent and explaining his symptoms in unloved terms.

“I had a happy childhood,” Jimmy will tell you. After his mother died—he was nine—his dad sent him out to live with his sister and her husband in Iowa. They were thoughtful, religious folks—Quakers, I believe—and owned a farm. It was a fine place to grow up, to go to school. Although Jimmy never had any aspirations for farming, the only rebelling he ever did was to skip cleaning the chicken coops once in a while. In school, he was an A student in art, an easy mixer, the class athlete.

After graduating from high school, Jimmy headed west to California and Santa Monica College for a degree in Physical Education and, he hoped, later a basketball coach’s job. He’d won the Indiana State Dramatic Contest as the best high-school actor and this started him thinking. When a junior, he switched to UCLA and law. One day, he says, he finally faced facts. He quit school to tackle Hollywood. This was no cinch.

Hollywood didn’t exactly welcome Jimmy Dean with open arms. He managed to get an usher’s job at CBS-TV, landed a one-minute TV commercial for a soft drink (Jimmy danced around a juke box, sang the ad—for $30). An agent helped him get a few bit parts, but that was all. In one Rock Hudson film, he had two lines. (I bet Rock was surprised when Jimmy reminded him when they met for “Giant.”)

Realizing he wasn’t the Hollywood matinee-idol type and lead roles were not destined to come to him fast, Jimmy pocketed his last few dollars and climbed aboard a cross-country bus for New York. Arriving in New York, he made the round of Broadway producers, getting nowhere in a hurry. Finally, he turned to TV agencies, wangled jobs as an extra. At one time, he was a stand-in for contestants on “Beat the Bank.” They tested the consistency of custard pies—later to be thrown in jest at contestants—by throwing them first at Jimmy.

Jimmy says there were plenty of nights he’d walk up and down Broadway, alone and pretty despondent, sure he’d never make it. Plenty of times, too, when he didn’t have the rent or food money. Temporary jobs—and a series of little miracles—helped tide him over.

His first break on Broadway came in a rather peculiar way. He was told one evening of a job opened for a crewhand on a sloop—and he needed a job. Besides, the skipper knew someone who knew someone who might arrange a tryout. What could he lose, Jimmy decided. He took the job, got the tryout, won the role—and the play, “See the Jaguar,” was a flop. It did one thing for Jimmy though—it brought tv leads, gave him money for good drama coaches. With his top performance in the hit play, “The Immoralist,” he received rave notices, won the David Blum award for the most promising newcomer of 1954 and caught Hollywood’s eye. Not easy? Jimmy’s the last one to tell you it was. I doubt whether he’ll ever forget those days or the people who had faith in him.

Believe it or not, Jimmy’s a sentimentalist. I remember a hot afternoon, soon after we started shooting “Rebel.” We were sitting around, killing time, while the lights were being adjusted and readied. I hardly knew Jimmy then, so I busied myself with a manicure. I think he was reading a book—on astronomy or bull-fighting, I don’t remember which. Neither of us said a word. There was only the constant hum of voices, directions and moving apparatus in the background. Then, quite by accident, I looked up. Jimmy was sitting with the widest grin.

“Penny for your thoughts?” curious.

“Aw, guess,” he teased.

“Thinking about your new sports car,” I offered.

“Nope.”

“Your new stallion?” I guessed, knowing Jimmy was forever running down to Santa Barbara after work to ride and exercise Cisco.

“Nope,” he answered, arching his eye-brows in that funny way he does when teasing.

“I got it,” I fairly screamed, delighted because I felt I’d outwitted him. “Your new sixteen millimeter movie camera.” Jimmy had bought it only yesterday. It cost two hundred dollars with special lenses and I knew he had saved up for it.

“Nope,” he said quietly, in his soft-spoken way. “Remember that scroll? The one I got from the folks back in Grant County? I was just sitting and thinking how nice it was for those three thousand people to sign the scroll, to tell me they liked my acting.”

Jimmy’s proud to be an actor, don’t ever doubt that. But it’s not for the fame, the glamour, the money. It’s the sense of achievement, the thrill of doing a good job. “I’m an actor not a personality,” he’ll complain, sometimes giving the wrong impression, getting labeled non-cooperative, ungrateful.

I had plenty of opportunity to see how grateful Jimmy Dean is to his fans. “Rebel” was shot all over Los Angeles and we had a chance to meet a lot of people. For one sequence we used the Planetarium and some high-school students. I had a late call the first morning so I arrived at the Planetarium after Jimmy.

Rushing to makeup, I turned the corner full speed, came to a dead stop! Sitting in a big old trash can was the star of “Rebel”—Hollywood’s newest, brightest, most talented boy actor—James Dean. Crumbled up in an awkward ball, he busily signed autographs, exchanged stories—very obviously unaware that he’d been pushed there, and equally unaware of his position or dignity!

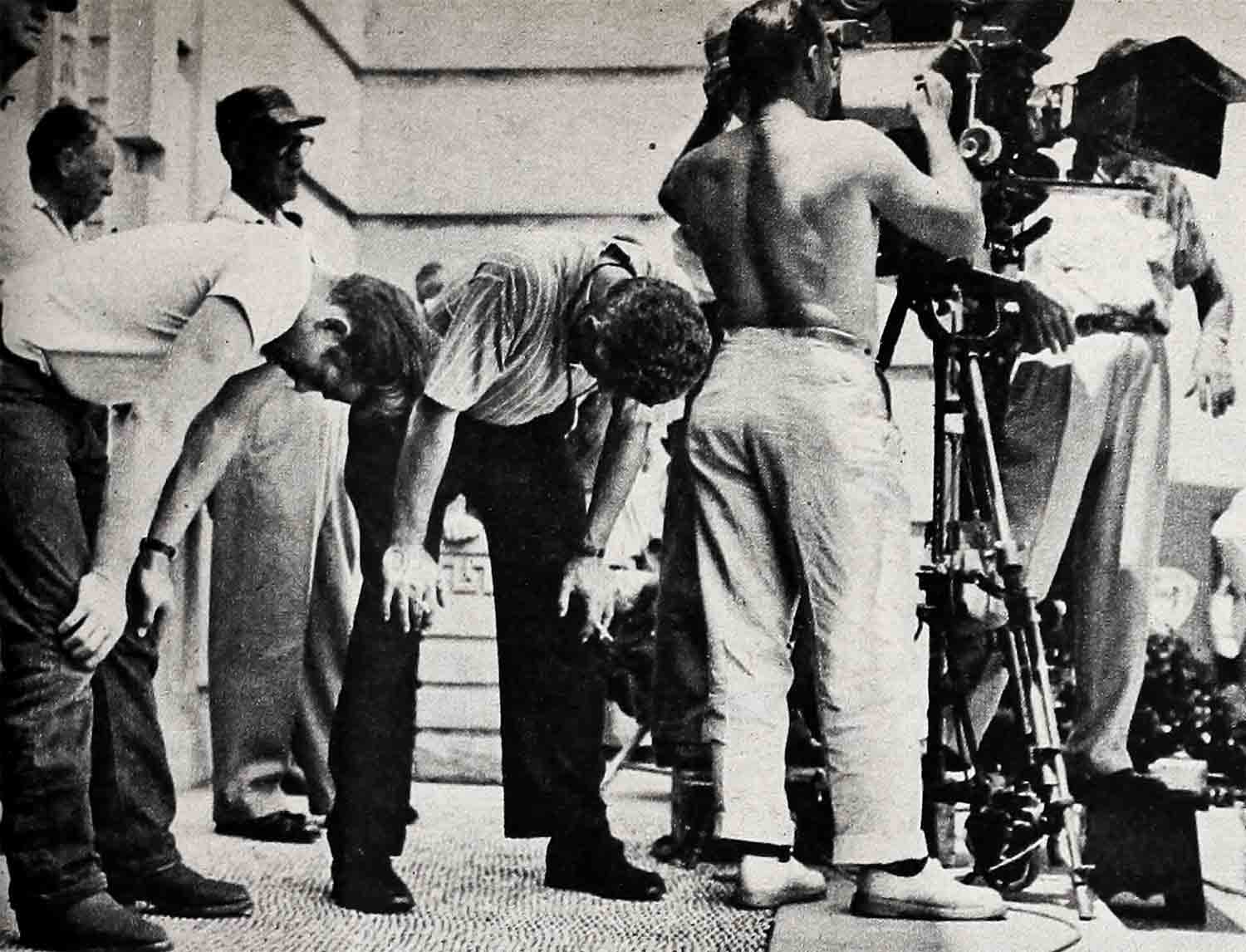

Photographers have been reported to complain that Dean is uncooperative. If so, that doesn’t explain the twenty minutes I had to wait for him to go to lunch.

Everything was humming along smoothly and we all found ourselves working a little longer than usual one morning. When lunch was mentioned, we realized we’d have to cut it short, so I hustled my belongings together, plus Mr. Dean, and we started for the commissary. I hadn’t noticed, but Jimmy, in his uncanny ability to sense people’s needs and problems, did. Standing off by the camera were three women, one shyly pushed her companion toward us.

“Can I do something for you?” Jimmy asked.

“Would you mind—posing for a picture for us—” she hesitantly inquired.

“Sure,” obliged Jimmy.

He hammed it up with me, stood on one foot, clowned around, posed and postulated until their hearts were content. A shutter bug himself, he offered composition suggestions, pointed out camera angles and gave tips on lighting—while I starved.

When I badgered him, in a deathlike whisper, about my hunger, he looked surprised. Then, like a little boy, said, “Aw, we’re having fun.”

Despite stories, Jimmy Dean does have fun. Acting can be fun. In “Rebel” I play my first grown-up film role and I also get my first kiss—from Jimmy. There’s no sense denying it, I was a little nervous.

“You look green,” Jimmy complimented me while we waited for the signal to begin the love scene. “And you know how green photographs in color.”

I managed a grin, I think. I really can’t remember. I felt like a fighter before a match—let’s go in and get it over with. Jimmy was saying something, but all I could think of was, “Is this the way—should I do it the way I rehearsed? Maybe that was too smooth. Maybe I should fumble a little.”

“Come on,” coaxed Jimmy. Suddenly I realized we were on. Complete silence. Then—“Roll,” shouted the director and the camera began clicking.

It was Jimmy’s move. I listened to him and felt almost inspired. He played it so gently, he brought out the best in me—under the circumstances. Then came the kiss. I heard the director call “Cut,” but the cameras seemed to be grinding away. I didn’t exactly know what to do, but I had no choice. Jimmy held and held and held. Might as well enjoy it, he kidded afterwards as I turned from green to red. But the nervous spell was broken. His kidding did it; I relaxed and the rest of the shooting went like a breeze!

Comes a big dramatic scene, Jimmy’s the opposite. Boy, is he intent. I didn’t know what he was going through the first time he prepared for an important scene.

“Hi, Jimmy, what are you doing?” I asked. He mumbled something—and completely unlike him—made it plain he wanted no conversation. He was kind of working himself into the role. Flaying his arms about, going through a bicycle-type movement with his legs. “I’m concentrating,” is all he said.

“By doing that?” I asked, sure that he’d be worn out before he began the scene. Patiently, he put up with me. “It gets me in form.”

I left him. By the time the cameras rolled, he was no longer Jimmy Dean. He was the confused, rebellious, unwanted Jim of “Rebel.”

Something went wrong, lights or camera position, and the director called cut to the scene. Jimmy stood where he left off, motionless. Then—and I remember this clearly—one of the fellows went up to him and started to kid. Wow! Was Jimmy furious. He made it clear, between breaks, no talk. He has to stay in “character.” This is true even when it takes a whole day to complete a scene.

Later that afternoon, Jimmy was scheduled to finish the sequence. It was hot, the cast had worked hard all day and most of us were exhausted. I had one idea—shared by the rest of the cast and crew—let’s go home. “For those who aren’t in the last scene, scram,” came the welcome reprieve.

For some reason, we hung around for a few minutes—and I’ll never forget this experience. Cameras rolled, the set quieted and Jimmy began—to go into one of the most tragic, heartbreaking scenes I’ve ever seen. One by one, members of the cast returned and stood, gripped by the tremendous emotional impact of the moment. We were carried away. At the end, not one of us could honestly confess there weren’t tears in our eyes. It was electrifying.

Director Nick Ray asserts Jimmy is the finest actor for his age he’s ever directed, also adds that, contrary to reports, he’s a breeze to handle. For his fine work and cooperation, the production staff gifted Jimmy with a bicycle. As for me, I’m greatly indebted to him for his stimulation and help. There’s no question, Dean’s great talent.

For the future, Jimmy hopes to direct. For the present, he hopes to act, to vary his roles, to grow as an individual, learn as a professional. He studies acting techniques, writing, photography and the stock market! To direct and produce, he grins slyly, you need money, too. With his new Warners contract, he’ll do nine films in the next six years. He’d like to return to the stage, maybe try Hamlet some day. This year, he may wind up playing Romeo for a color featurette for Warners. Talks about doing the life of Harry Greb, the middleweight fighter of years ago, too. He and stand-in Mush Callahan, the champion ex-fighter, were forever “getting into shape,” for the role.

Jimmy’s 5 foot 10 and looks short (“because I slump,” he says), but he’s amazingly strong. Always a good athlete, he keeps in trim by swimming, playing volleyball, sailing and deep-sea diving. Ask, “Tennis anyone—boxing, riding, baseball or basketball”—and you’ve got a partner. But his chief love, I think, is bullfighting. Someday he wants to get into the ring himself.

I don’t mean to imply that Jimmy isn’t a character. He is—but a pretty interesting one. He’ll hardly say a word in a crowd until someone mentions architecture, hi-fi, sports-car racing or music. Then try and stop him. Question him about himself, he’ll answer straight. Show some ulterior motive, he’ll clam up even if you’re a V.P. in charge of world news. He can talk about carburetors in one breath, discuss William James’ pragmatic philosophy in another and be off on the subject of design two minutes later. If he has a free moment, chances are you’ll find him behind a serious book or buried underneath a pile of travel folders. Mention music and he’ll go mad—over native African rhythms, Beethoven’s Ninth or progressive jazz. Take a drive with him, and you’ll be tuned in to classical music. Jimmy studied violin as a child, has picked up his studies again with Leonard Rosenman, who was his roommate in New York and is now a Warners composer. Invite him to Sunday dinner, he’ll accept. What’s more, he’ll win your parents over with charm and intelligence.

An oddball, did you ask? Yes, if you call talent odd. A weirdy? Maybe, if you don’t like individualists. Sullen? Never! Jimmy Dean’s too busy living to sulk.

THE END

—BY NATALIE WOOD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955