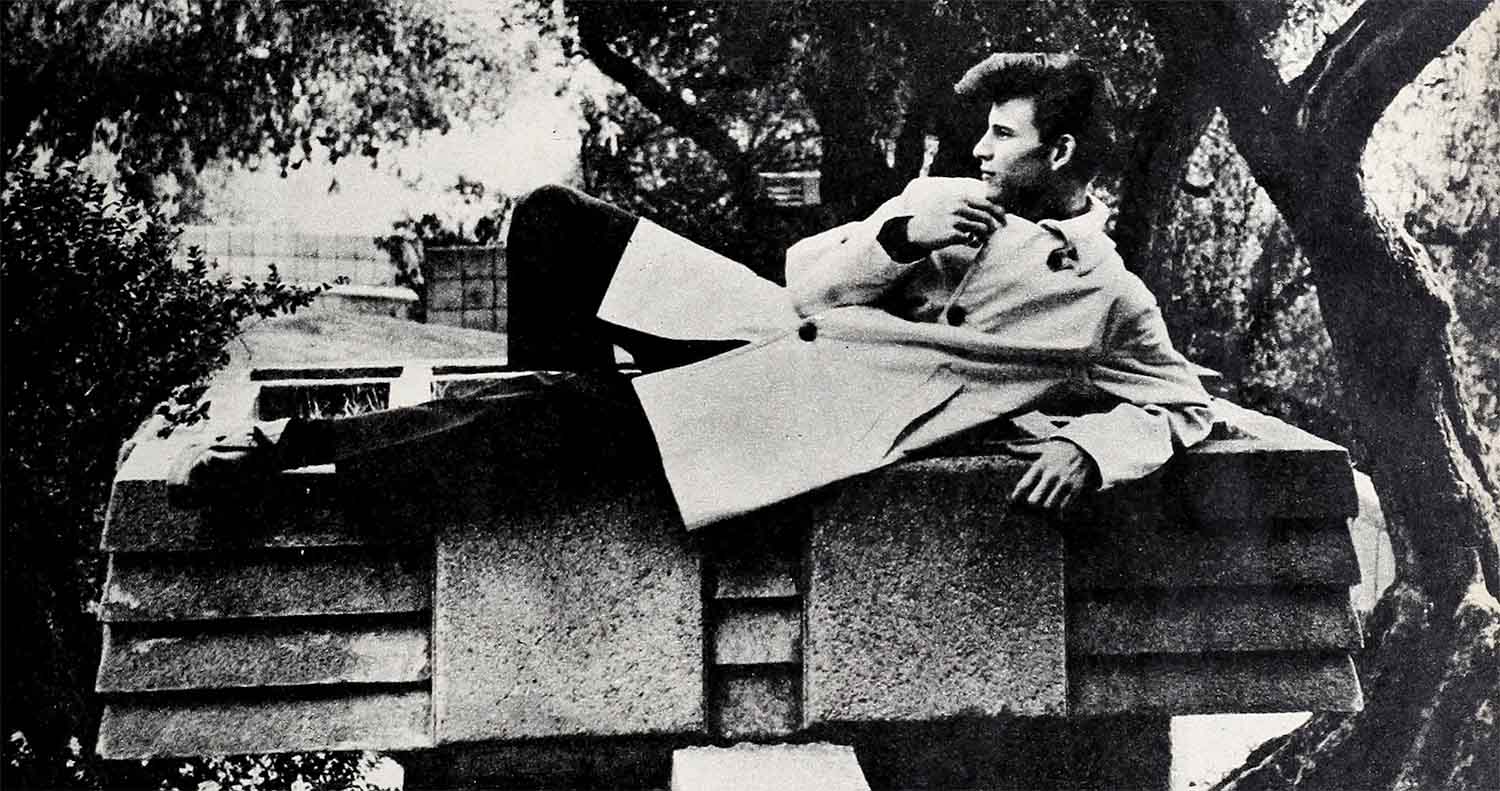

“What Can Anybody See In Him?”

When I turned into the driveway of her home, that night, and cut the engine, I was scared. I looked okay—I was wearing my good black suit and I had my dad’s car and I had enough money so I didn’t have to worry about what she wanted to do, but the truth was, I didn’t know Ann very well. She’d come to Philadelphia, from New York, a month before. She was the smartest girl in the class, and the prettiest, too. She had dark hair and big eyes and she wore cashmere sweaters with a single strand of pearls. From the first day, I had sort of admired her from afar and I couldn’t believe she had really agreed to go out with me. I was worried sick. All I could think of was, “What am I going to say?”

As I sat at the wheel trying to get up the courage to go to the door, my mind raced back to the time when I was ten and on the Paul Whiteman TV “Teen Club.” I’d been scared then, too. And I was remembering the day, just about a week before, when I’d walked into the school cafeteria and heard a girl say to a bunch of the other kids, “What can anybody see in him?” That remark still kind of haunts me. Whenever I’m scared, I repeat that question to myself and right away I start getting depressed. But this was my first big date since that remark and it was kind of extra tough for me.

A dog barked, somewhere, and I came to. It was ten past eight. She’d think I wasn’t Corning. I ran up the steps, two at a time, and rang the bell. I was afraid her father was going to answer the door. I never know what to say to fathers. After they’ve shaken your hand and said. “Sit down. Sit down, my boy,” there’s always a dead silence and I kind of squirm inside. But Ann answered the door herself. She looked so cute in a pale blue dress, her hair up in a shiny ponytail.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m all ready.”

“Good,” She slipped on a coat and we went down the steps and I helped her into the car. I wanted to tell her how pretty she looked but the words just wouldn’t come out.

“It’s a lovely night,” she said as we drove off.

“It sure is ” That was a brilliant answer, I thought miserably and then added something just as stupid. “I’m glad it didn’t rain.”

“Mmmmm.” Ann settled her head against the back of the seat. “This your car?”

“No, it’s my dad’s.”

“It’s nice. I like convertibles.”

“Me, too.”

“Where are we going?” she asked expectantly.

“I don’t know I thought maybe you—” I could tell already she was disappointed and a little bored. You can always tell. “Doggonit,” I thought desperately, “give me a chance, Ann! It’s just that I’m kind of shy. I’ll warm up in a little while, honest!”

But it doesn’t seem to me that I ever did. All evening long, just as I’d get ready to say something, she’d turn her head or speak.

We ended up at a Debbie Reynolds movie. Debbie is Ann’s favorite star. We had ice cream afterward and played some Bobby Darin and Frank Sinatra records—they’re favorites of mine—and then I took her home. She was polite at the door and thanked me but I knew she’d never date me again.

When I got home, I tiptoed up to my room. My grandparents were in bed and so were my mom and dad. The house was so quiet. I wished Bunny was there. Bunny is a cocker spaniel I had once. He was blond and had green eyes that glowed in the dark. I loved that dog. Whenever I was depressed, I’d cuddle and pet him. But Bunny wasn’t there. And I was alone. I didn’t see how I could face Ann in school the next day. She probably thought I was a drip and a bore. And I could hear that strange voice saying, over and over, “What can anybody see in him?” I put my hands over my ears but it didn’t stop. Then I began pacing up and down the room. A few moments later, I stopped to look in a mirror. ‘I’m not too bad looking,” I told myself, “but nothing special, I guess.” And I found myself sighing. “Maybe they’re right,” I thought.

Nearby, stood my set of drums. I picked up one stick, wanting to hit the drum the way I felt I wanted to hit out at the world. My parents had given me those drums the Christmas I was fifteen. I longed to play them to beat away the frustrations, the hurts, the mixed-up emotions. But instead, I just rubbed my hands over the smooth wood of the drumsticks.

My first love

I was crazy about drums. They’d been my first love. You didn’t have to talk to them, they talked to you. I always smile when I remember how I used to drive my poor mother crazy banging on her pots and pans, and it was awful how I cracked the arms of the leather chairs in the living room using knives for make-believe drum sticks.

Maybe Ann would have liked me better when I was little, I thought wistfully. I wasn’t so shy then. I was only nine when I first stepped onto a night-club floor to entertain; and I’ll never forget it. When I saw the master of ceremonies standing in the spotlight holding that hand mike, my heart started banging like crazy. But I wasn’t shy and quiet the way I’d been with Ann. I was—well-scared just for the moment, especially when he announced, “We have a little fellow sitting in the audience—Bobby Ridarelli!” But as soon as I got up to perform, I was relaxed. Maybe it was because so many people were cheering me and wishing me well. Maybe that’s the answer to the problem—although I didn’t think about it until years later—maybe all you need is one person or one occasion when you know there’s someone who believes in you, who thinks you’re something special, and then you’ve got your confidence for always, whatever anyone may say.

I remember I did impersonations of Johnny Ray, Louis Prima and Dean Martin, and the audience seemed to like it. It was like I was two people. When I was performing I wasn’t little Bobby Ridarelli at all, I was a performer, confident and sure of myself.

“Give me another chance, Ann,” I thought, that night. “I’d like you to tell me all about yourself, and I’d like to tell you all about me. How I love rock ’n’ roll and Frank Sinatra and my grandmother’s pizza pies, What fun it was being a little kid and growing up in Philadelphia; playing drums in the school band and performing in the variety shows; going outside after supper, on warm summer evenings, and playing ‘cops and robbers’ with the kids, or ‘take-a-giant-step.’ Oh, I wasn’t perfect, Ann, I got into mischief, too. Like the Hallowe’en we tied ropes to people’s doors so they couldn’t get out. Gee . . . I loved Hallowe’en. You could get away with a lot then. But you know something funny? Sometimes, even when I was real little, I’d feel I was wasting time just playing. Often, I’d go home and practice the drums, sitting in my room for hours and hours. I was determined to succeed, to get ahead. And everyone said I had talent. So, I’d watch performers on TV and try to copy their style, if I liked it, and see if I could learn what it was that had made them successful. I think some of the other kids thought I was crazy. But it made sense to me. I’d always wanted to be somebody, be a big success, make enough money to help buy a house for Mom and Dad and get him to retire from his foreman’s job.

I was growing sleepy, my eyes began to close.

I woke, the next morning, surprised to find myself lying across my bed still dressed! At school, I purposely avoided Ann. I went into the cafeteria at noon and got a bowl of tomato soup. I kept my eyes down. I felt like everyone could tell what a dismal flop I’d been the night before. Ann was sitting a few tables away with a group of friends and they were laughing real loud. I could feel my cheeks getting hot and I was more embarrassed than ever. Then, they were quiet and suddenly I felt a hand on my shoulder. I looked up and it was Ann. She asked if she could sit down and I nodded yes.

I was so surprised, I didn’t quite know what to say for a moment. I guess she must have sensed this, because she looked at me so kindly and said, “I hope you didn’t mind my coming over like this.” “Nope,” I gulped. “Please stay.”

“I don’t know quite how to tell you,” she began. “I guess I wasn’t—well—very nice last night.”

‘‘That’s all right,” I said softly.

“You didn’t think that . . . that we were laughing at you over there, did you? You kept looking over in such an odd way.”

“Of course not.” I shrugged but I was sure I gave myself away.

“Ann—” I said, “I wanted to tell you—”

She touched my hand ever so lightly. “It’s okay, Bobby. I was sorry I didn’t tell you last night—I like you.” She smiled. “Next time you pick the movie.”

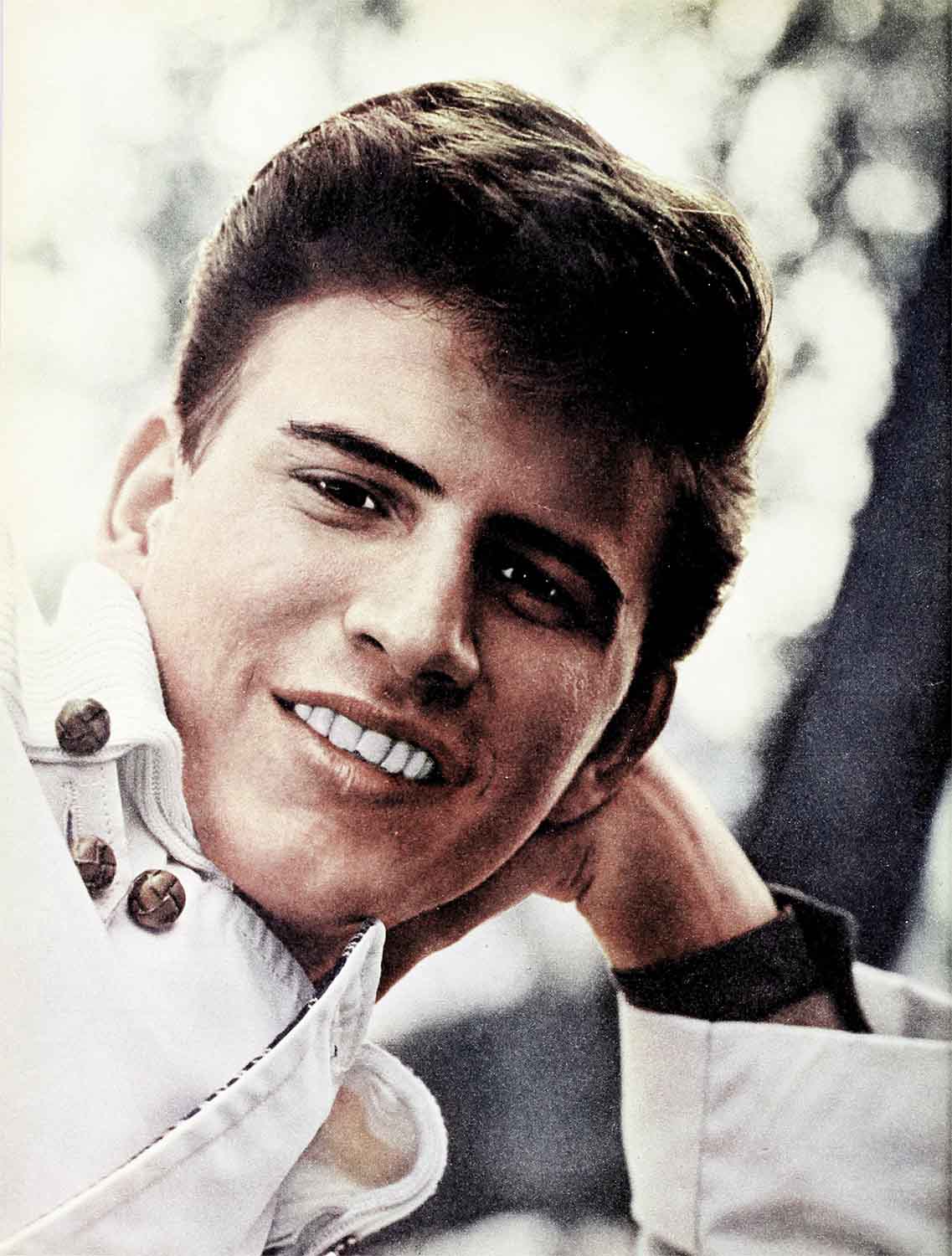

I smiled back at her. “You know, Bobby,” she said. “when you smile like that, you get, well, sort of a glow about you, as though you’re happy from ’way inside. It makes you seem kind of special.”

Suddenly, my heart was flipping and I was grinning like a Sweepstakes winner. I felt I could conquer the world. I felt maybe I was something special after all, if only to Ann. It’s like I said, I’ve learned, now, it just takes one person to give you confidence.

It wasn’t long after that, that things started to break for me. I was signed by Cameo Records and was lucky enough to have some hits like “Wild One” and “I Dig girls.” But when you get something you want in life, you sometimes have to pay for it with something else. The company Ann’s father worked for sent him abroad and she and her family went to live in England. Then I had to make so many appearances, I had to leave the Catholic school I’d been attending for ten years. I felt pretty bad, that last day, and when my family suggested a tutor I thought, “Me . . . a tutor?” It just didn’t sound right. But, sure enough, I got one, and even though I felt rather stupid, at first, I finally settled down.

From then on, most of my time was taken up with tours. I was with “Dick Clark’s Caravan of Stars” for six weeks of one-nighters, traveling from Texas to Canada. Then I did “Greatest Stars of ’59.” Frankie Avalon was with this one. Frankie and I at e great friends. We grew up together. He used to live only about a block from my home in Philadelphia and, at first, we were both just like the other kids. But then the two of us moved on.

I love the tours. Besides, the audience reaction inspires you. Even the squealing. You feel closer to the kids. TV is great, too, but the closeness isn’t there. On a stage, you feel kind of confident when you see the audience out front screaming for you and rooting for you. Sometimes I pick out a face in that audience—maybe a pretty girl with cute blue eyes or silky hair—and make-believe I’m playing just to her. She looks up at me as though I’m kind of special and suddenly I forget again all those fears I had about being a nobody and a bore.

When you’re in the theater, you work extra hard because you feel you owe it to the fans. They’re the ones who put you where you are. I’ll always be devoted to them. Even when they get a little out of hand. Sometimes they get excited and run up to the stage with cameras, but the M.C. usually knows how to handle them—and as a performer you have to understand it. When they like you, I guess they feel they’re a part of you.

It can get kind of rough, though—boy! Sometimes, they have to call the cops out. The kids don’t mean anything by it but there are so many of them and they get so excited. once, in Scranton, they pulled me to the ground and all the buttons came off my jacket. They wanted something belonging to me—a handkerchief, a comb—anything. They even grabbed my hair, and ten hands pulling at once—that hurts!

I always look forward to getting home to Philadelphia and my own group of friends who know me real well. I don’t feel shy or uncomfortable with them. We hang out in the corner soda shop and talk about what happened while I was away—did Anthony break up with Charlotte—things like that. We play records a lot. I especially like the jazz groups. I’ve got so many records at home, that they’re going to run me right out of the place! When I’m on the road, the distributors give them to me. I haven’t even heard half of them.

I’ll have to admit, though, I’m still shy when I meet new people. I still squirm inside and have trouble making conversation. Now that I’m eighteen, maybe I should be getting over it, but maybe I never will completely. Maybe it will always take me a little time to warm up, “like the engine of a car,” my mom says. All I ask is that people give me a chance and don’t judge me on a first impression.

Like when I did the Danny Thomas TV show. I had never met any of the cast before, and when I wasn’t on, I’d sit quietly in a corner, observing. The first few days, I think they thought I was holding back, and then, one afternoon, the director said, “Okay, Rydell, on your feet. Not so much noise over there,” he added a little sarcastically. Suddenly the whole set was quiet, everybody was watching and waiting to see what I was going to do. I was in the mood to kid back so I twisted up my face, put my hands in my pockets and said playfully, “So, fellas, what’s there to stare at?” They all laughed and the walls were gone and we were friendly.

If it weren’t for Frankie . . .

Actually, I do like to have lots of people around me and I love parties—all kinds— it’s just that maybe I’m quiet because I still don’t always think I have much to offer. I had a birthday party last April 26th. I was eighteen. We had a huge fancy cake from the bakery, but there was one from Mom and one from Grandma, too. They always bake me cakes. It’s like a family tradition. It was a swell party—about forty people. I liked it because I knew everyone so well. And in a crowd like that, you never have a chance to get lonely or shy. I remember when I was on the coast, for two weeks, to do the Red Skelton show, I didn’t know a soul and I really had the blues. I’d go down to a pool and swim a little but it wasn’t any fun being all alone. I didn’t know what to do, or who to talk to. I’d just sit watching everyone else have fun. I guess if it weren’t for Frankie Day I’d have gone nuts. Frankie Day is my manager. He found me in Atlantic City when I was down there with Frankie Avalon, who was playing trumpet with a group called “Rocko and His Saints.” I was fourteen then. It was a Saturday night and I sat in with the Saints and played drums and sang. Frankie Day said he thought I had something, and asked if he could see my father. I was so excited I wanted to run all the way home.

When he asked Dad if he could manage me, my dad wasn’t very impressed. He was kind of discouraged at the time. People had always been building dreams for me and nothing ever came of them. I’d get real depressed, too—go close myself in my room and play records and not talk much, and that worried Dad. But Frankie managed to convince him he was sincere. He even got Dad to let me shorten my name from Ridarelli to Rydell, which seemed kind of strange-sounding at first. But I grew to like it. It sounds sort of grand. Then we really went to work.

You know, for over two years, I had to take dancing and voice lessons, and I learned how to sharpen my performance. Things didn’t happen overnight, for me. As a matter of fact, my first three records were big flops. But then “Kissing Time” came along and things have been good ever since. The mail is coming in real good now, thank goodness.

When I do date, I like to take in a drive-in movie or go dancing. I love to jitterbug. The faster the better. I can get by with slow dancing but I’m not very good, although I don’t think I’m as self-conscious as I used to be. Like I was that time with Ann. But it still hurts when a girl turns me down or looks bored—even for a moment.

I’ve thought a lot about girls since that day I dated Ann and dated a lot of them too. I’ve even formed opinions, I know now that I like a girl to have a nice personality, a good sense of humor, dress conservatively and not wear too much make-up. I prefer small girls because I’m only five feet eight and weigh 120 pounds.

Sometimes I think maybe I can even afford a car of my own now. I want to get a T-bird. I like them because they’re small and powerful. I still don’t have that house for my folks, either, but I’m getting closer all the time. A movie would really do it, although I’d have even less time for dates than I do now. Movie schedules are pretty hectic.

Sometimes girls ask me if I’m superstitious. I’m not a bit, but the fans send me rabbits’ feet and charms. One girl sent me a medal blessed by the Pope. I wear that all the time.

I like it when they send me things. Or even just letters. It reminds me that they still believe in me and want to hear me. I guess we all need to know this in some way or another—that people want us and believe in us. It helps us get over those rough spots in life . . . like that time for me when those girls made me feel two feet tall by remarking, “What can anybody see in him?”

THE END

HEAR BOBBY RYDELL SING ON THE CAMEO LABEL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1960

No Comments