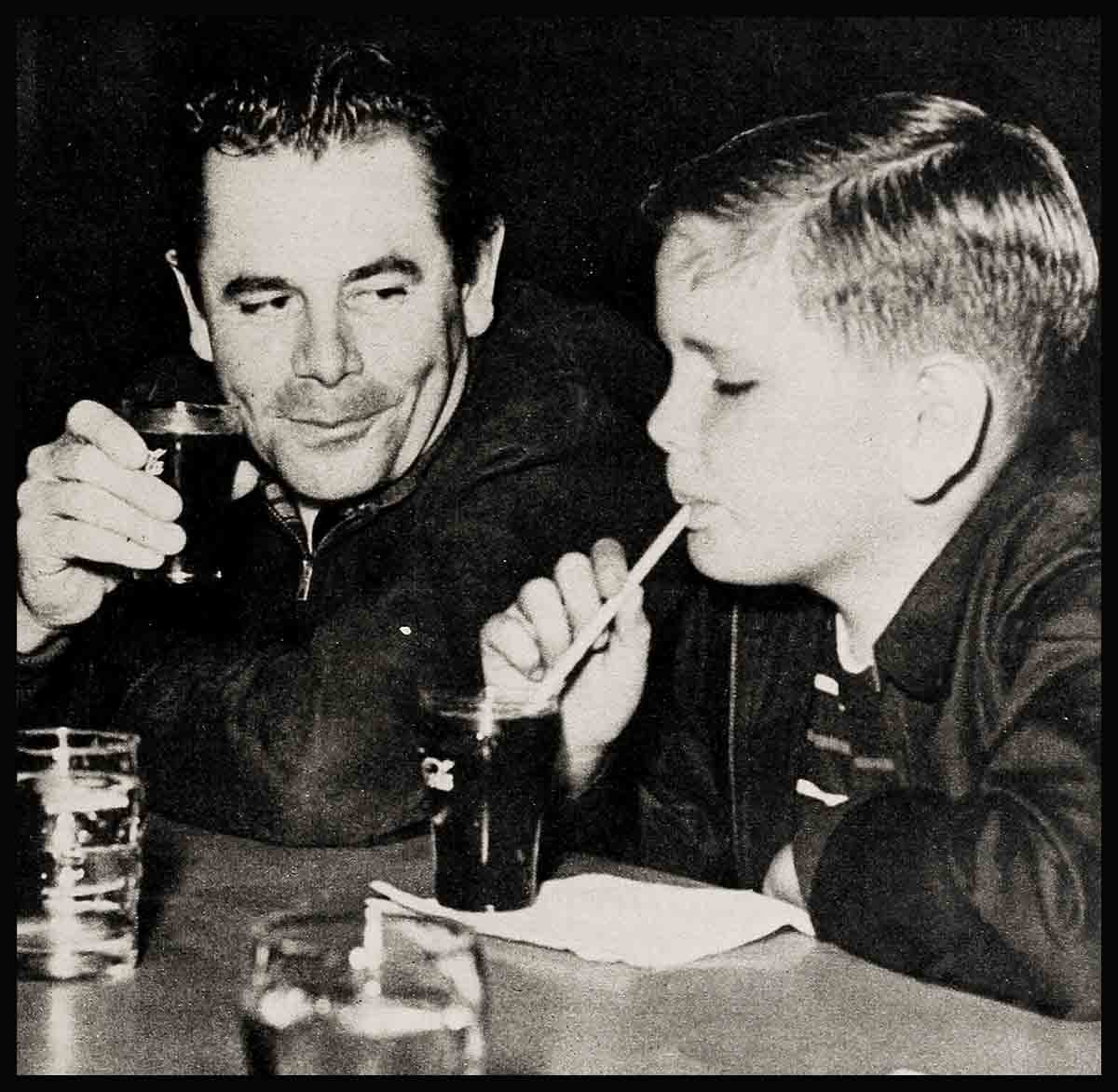

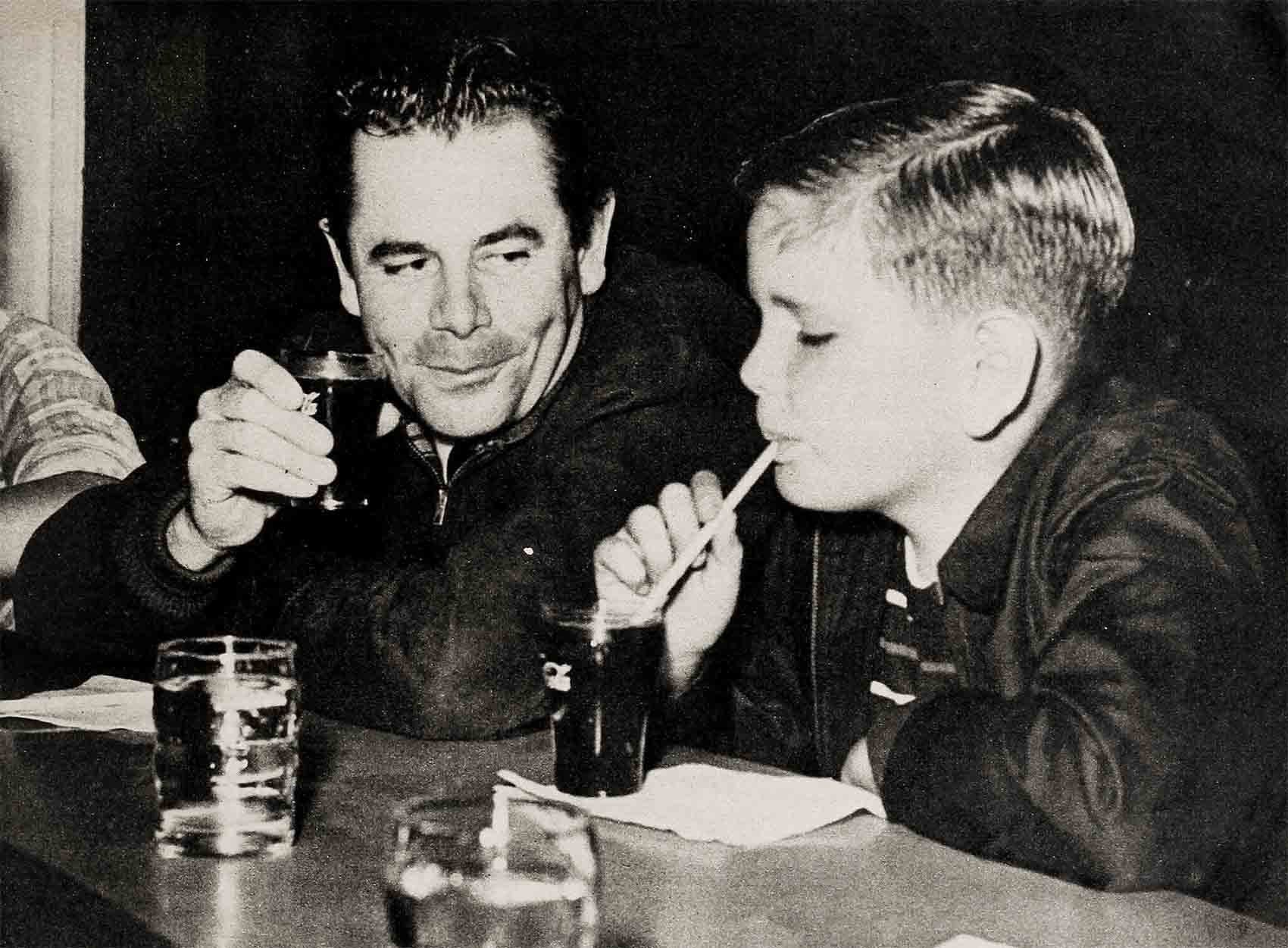

Like Father, Like Son—Glenn Ford & Peter Ford

A terrifying object swooshed suddenly into the velvet sky over Beverly Hills, spitting blue flame and hissing ominously. Briefly but gloriously it dipped, darted and corkscrewed crazily around the roofs and gables of mansions belonging to such eminent citizens as the Fred Astaires, David Selznicks, William Wylers and James Masons. Then it clanked to burnt-out oblivion.

Windows had lighted up like Christmas trees in this select residential section. Doors flew open and telephones jangled, as one private number dialed another. What was it—a flying saucer? Had push-button war begun? Neighbors in bathrobes chattered like squirrels and peered into the heavens.

One calm householder merely yawned and kept his eyes on his TV set. “It’s nothing to get worked up about,” he reasoned. “Just that Ford kid down the street.”

“Which one?” his wife asked him.

It was a legitimate question. Down the line in a big brick house a couple of Fords are growing to look and act like each other more and more every day. At that tense moment the pair of them, a husky nine-year-old called Pete and a tall thirty-six-year-old called Glenn, stood rooted in the darkness of their backyard, staring at each other with expressions compounded of rapture, fear, wonder and guilt.

“Dad,” exclaimed the one named Pete. “It worked!”

“Yeah,” admitted Glenn a little shakily, “it sure did. Come on,” he suggested, “Jet’s duck into the house before the cops come. I thought you wanted that cigar can and the old movie film for a stink bomb.”

“Well,” explained his son, “it’s like this: you cram the film into the can, poke a big hole in the top, light it and it’s a stink bomb. But if you put little holes in the bottom, stick in a fuse, put on fins and rig up a couple of boards to launch it—then it’s a space rocket.”

“I see.” “Dad,” pursued Pete, “have you got another empty can and some more of that old film?”

“Not on your life.”

“Then—uh—can I have that chemistry set for my birthday—I’ll keep it in the hut.”

“We’ll see.”

“Dad,” queried the youngest Ford, “what you staring at me for?”

“Oh, nothing,” grinned Glenn Ford quickly. “Nothing at all.”

Flashing through Glenn Ford’s mind even as he ducked a fatherly decision was the picture of another kid, skinnier and with darker hair, but about the same age and with the same adventurous thrust to his jaw. A kid named Gwyllyn Samuel Newton Ford who also had a hut out in his backyard in Santa Monica—with a chemistry set inside. Glenn was thinking about the time he traded a World War I helmet for a big can of a “chemical” he could add to his set. The label was gone and the can was rusted shut. He and his friend decided to open it. Inside was a hunk of crumbly stuff that glowed when you knocked it off. Luckily, he’d had sense enough to use gloves and it was great rubbing the junk all over the hut, making luminous skulls and crossbones on the wall, until suddenly the chunk started hissing and smoking. They beat it outside with only a second to spare before it exploded, caught the other chemicals and blew the whole shack to splinters. The chunk was pure phosphorus.

“Mum’s the word about the rocket,” he told Pete. “Now, let’s say our prayers and hit the sack. I’m sleepy.”

More and more, it seems to Glenn Ford, he looks at his son Pete, and it’s like looking in a mirror. He sees himself and something else—his own second chance at life. It’s a gratifying, even thrilling, view most of the time, but a little scary, too. That second chance is important to Glenn. Pete is the only child of two only children and it looks as though he might remain the last of the Fords. No wonder his old man stays awake some nights staring out the window and adding himself up. Pete is no longer a baby; he’s growing up and sizing up. His dad is still his hero but, as Glenn sometimes puzzles a little wryly, “How can you stay the right kind of a hero when your checkered past keeps jumping up at you?” Like just last summer down in the jungles of Brazil.

Glenn was there on location making The Americano. Pete was there and Ellie, too, because of a chance remark his kid made. When Glenn came home with his travel plans Pete had asked, “Say, Dad, what’s it like to ride on a train?”

That handed Glenn Ford a jolt.

“You mean you’ve never been on a train, pal?” he gasped. But even as he said it he knew it was true, and for a special reason he felt shame and neglect.

His own dad was a railroader with the Canadian Pacific, and as a kid trains were the most glamorous, exciting and wonderful objects in the world to Glenn. Even today when he hears a distant whistle or just the tinkle of ice in a water pitcher, it brings back those dining car sounds of his boyhood and makes him itch to climb aboard. At the studio they’ve long since given him up for any other kind of travel. The company flies off to locations—as they did last year to Oklahoma for The Human Beast—but not Ford. He climbs happily aboard a rattler and they can count on him to show up two days later, cinders on his collar and rapture on his face. The first Christmas present Pete had was an electric train. The first book Glenn read to him was about a choo-choo. And what had his boy just said?

“Look,” Glenn decreed a little firmly, knowing that Ellie would have to be pried loose from home with a crowbar, “this family is going on a trip.”

So they had three delicious days on the Southern Pacific to New Orleans and then took a boat—Pete’s first—around to Rio, settling finally in a comfortable cabana at Guaraja beside the most beautiful beach in the world. But right at their back door was the Mato Grosso, daddy of the world’s jungles. That’s where Glenn worked and naturally Pete insisted on being by his side. Soon Glenn began to wonder if his family excursion idea was so sound.

Because where Pete wandered happily with his bug jar and butterfly net was also where panthers prowled, tapirs and wild hogs roamed, cobras, coral snakes and all kinds of poisonous things slithered. How Glenn ever played a part with Pete on his anxious mind, hell never know. Sure, he would have been as venturesome himself at that age, if he’d had that chance, but now he wasn’t that age.

The inevitable scare came when he took Pete and Ellie fishing on the bank of a tropical stream. If fish didn’t bite, as these didn’t seem to, Pete’s impulse was to wade in and see why not. They had all been eating apples and tossing the cores into the sluggish waters and suddenly there was Pete, in above the knees before he could be stopped. Glenn looked and his heart froze. Something glided at the speed of a torpedo right toward his son. A cavernous mouthful of jagged teeth yawned open!

What happened next is still sort of a blur in Glenn Ford’s memory. He screamed, “Pete!” and leaped off the muddy bank, meeting his thoroughly scared son halfway out of the water. Glenn threw him the rest of the way, then sank to the mud, trembling. The crocodile was going after those floating apple cores, but it might have been something else.

“Won’t you ever learn not to take chances? Suppose that crocodile, suppose—” Glenn sputtered. “You’ve got to be careful, boy! That was just plain crazy wading in that river. A stupid, dangerous thing to do—”

“Look who’s talking,” a voice cooled him down. Ellie’s. She was hugging their son, acting calmer but every bit as shocked. “The man who climbed the Matterhorn and pierced the Iron Curtain!”

That wave came over Glenn again. Here he was bawling out Pete for taking risks and—well—he knew exactly what Ellie referred to. It wasn’t the Matterhorn. It was Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Europe, and if ever there was a silly, reckless escapade that was it, for sure.

He was in Switzerland that year making The White Tower. It was winter— avalanche season—and what he knew about climbing Alps you could put in your left eye. But there was that big, beautiful, challenging hill and sometimes romantic Welshman Ford gets wild ideas from playing in moving pictures. So he found himself one day panting at the very last hut. From there you made a dash for the top—and if you didn’t get back before dark, chances were you’d never get back.

Glenn shuddered to recall it. A sudden blizzard, a slip, miscounted minutes for a greenhorn and—well, there wouldn’t be any pop today for Pete. As if that wasn’t crazy enough, he’d tackled the Aguille du Midi next—not so high but even tougher. That 100-to-1 luck was with him again. In fact, the plaque the Syndicate of Guides gave him for his climbs was Pete’s treasure. But Pete didn’t know the details.

The Iron Curtain thing was even more impulsive and rash. That was after The Green Glove in France, only three years ago. He was thirty-three and should have collected some discretion. But one thing had led to another. First he’d visited an old service pal in Munich and heard about the big DP camp at Fernwald down the line, where 25,000 cooped-up, homeless people milled around, hungry to hear about the Land of the Free. So he went down to raise some hopes. Elated by that experience, he got the bug to see Vienna. He bought a ticket on the Orient Express and at Innes, where the trains enter the Russian sector, talked to a G.I. sergeant named Blum.

“Hmmm,” frowned the sarge, looking at his passport. “With all these names, ‘Gwyllyn Samuel Newton Ford, known professionally as Glenn Ford’—chum, you’ll be a pigeon. The Russians won’t get it so they’ll toss you in jail just to make sure. Better lose the idea.” After a round or two of vodka it was, “You really want to go to Vienna?” And of course he’d said, “Sure!” Then the guards told him how to get on a cattle car, turn up his coat collar and not show his passport at all—sometimes it worked. But this time it didn’t. They caught him and hauled him before the American consul.

But then what did he do, after seeing the sights of Old Vienna, but get this stubborn idea to take home a rock from the Blue Danube to add to his collection from the Tower of London, Henry VIII’s castle, Alcatraz and scattered points he’d already visited. The American side was cemented in, so he strolled across the bridge to the Russian bank and filled his pockets. As he was bending over something jabbed him in the ribs—a rifle. On the other end was a red star boy. He made unmistakable gestures meaning “Gimme—and come along.” Well, Glenn lost all the Blue Danube pebbles except one which he hid. It is in his garden today. But to get it and Glenn free the Department of State had an awful hassle. The consul told him, “It’s crazy Americans like you doing crazy things around here that cause all the trouble.” He reminded Glenn that a newspaper reporter named Bill Oatis was then in jail somewhere nearby just for trying to get a story, not rocks. But Pete never knew how close his dad came to being another Oatis case. Pete might have been answering questions, “Where’s my Daddy? Oh, he’s over in Siberia mining salt!”

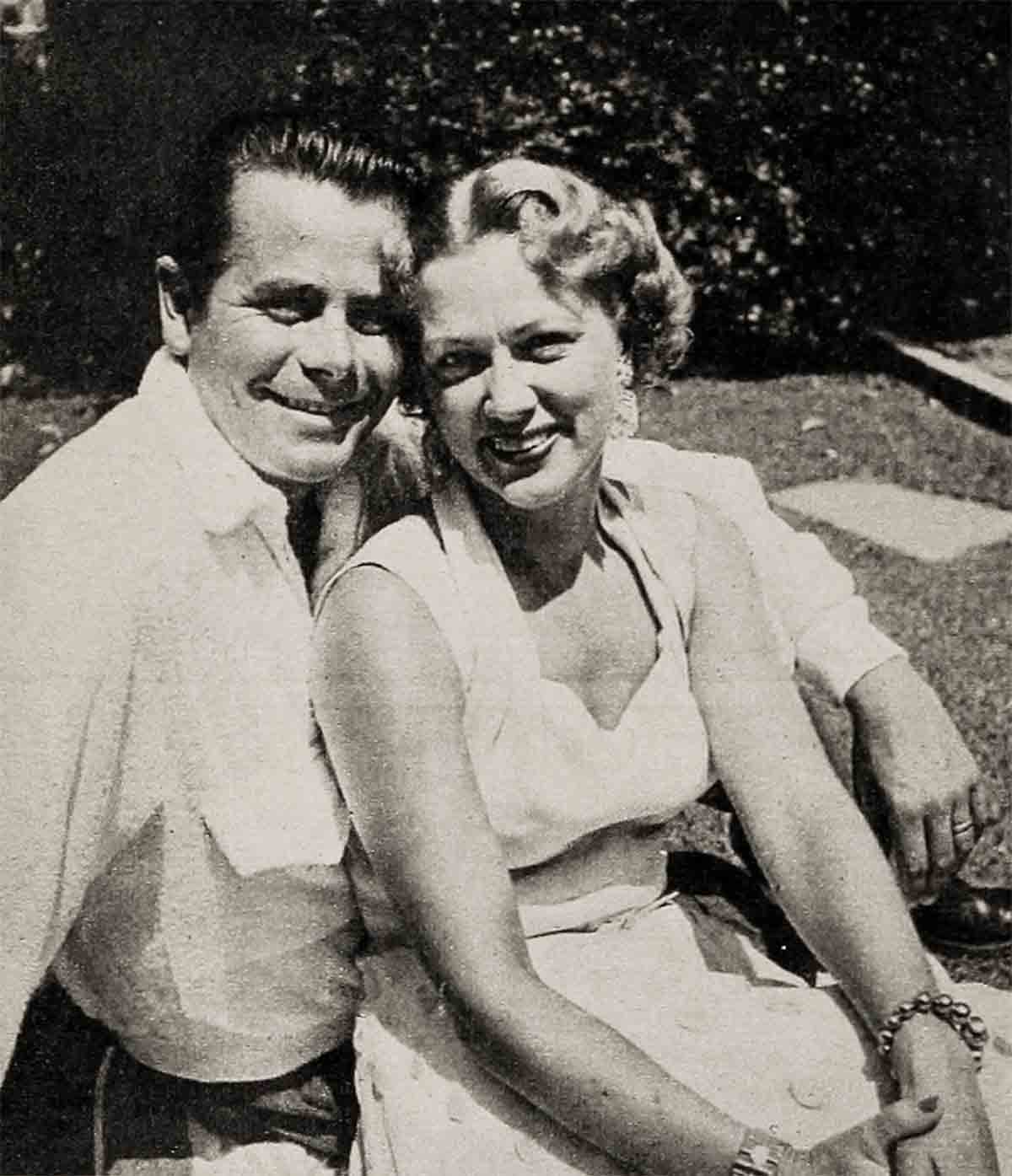

At such introspective moments Glenn Ford sometimes wonders if he’s a model block for the chip he sees before him. Actually, of course, Glenn is going through a common soul-searching sooner or later encountered by all fathers of sons. Actually, no dad, in Hollywood or elsewhere, has been closer to his son. And no parents—because Eleanor Powell has something to do with it too—have done a better job by starting a boy in the fundamentals. For faith, health and character, Peter Newton is an example of conscientious homework.

Pete has yet to go to bed without saying his prayers with either Ellie or Glenn, yet to miss grace at dinner. The Presbyterian church in Beverly is a family must, with Pete singing in the boys’ choir and Ellie teaching a Sunday school class. One look at Pete’s sturdy build—he’s going to be a bigger man than his pop—attests to the patience and ingenuity expended in getting him to clean up his plate. Setting the right example almost fattened Glenn out of pictures until he learned the ruse of heaping his own plate with impressive but low-caloried hunks of lettuce.

In matters of discipline and physical courage Glenn has been a stickler. When Pete gets cracked with a baseball and starts to water up, Glenn is prone to yell—to Ellie’s horror—“No tears—not unless I see the bones sticking out.” Being a hard-headed Welshman himself, he has encouraged thrift in Pete, a penny a pound for wood he stacked, fifty cents for the weeding job, etc. Pete is already a good business man. In Brazil when he uncovered a particularly repulsive but harmless giant beetle, the director got ideas to have it crawl over Glenn’s sweaty face in a scene. “I’ll rent your bug, Pete,” he offered.

“How much?” asked Pete, and haggled the dollar offer up to three. Back home the money he had collected went into an ancient power mower for his dad. He dug it up for five bucks around the neighborhood. And although it cost Glenn a hundred to make the thing run, he was proud of his kid.

Glenn knows that besides bugs Pete has collected the right instincts by now. He’s not worried about that or about the way they are instilled. You’re the right kind of guy and your kid can’t miss. You give him security, teach him manners, consideration and honesty, how to handle himself and how to stay away from danger. You feed his early hungers, prod his inquisitiveness with toys, flood him with books if he’s a bookworm like his dad, buy him records if he likes music like his mom. Give him love, understanding, encouragement and care. Simple enough. But what dents a wrinkle in Glenn’s brow these days are the nebulous issues, the yes-maybe-no problems a pop faces when a subtle yet all-of-a-sudden change takes place in his house.

Pete Ford will be ten on his next birthday, in fifth grade next year and already Glenn’s pride and joy is beset with vague questions. He’s knocking his brown head against the world, having scraps with the boys, puzzling encounters with females, angling toward the track he’ll follow to manhood. Glenn knows that now is the time for him to pitch the right answers Pete’s way. But how can you serve them up except from your own experience? After all, you have only a few opinions you’ve gathered on debatable subjects, some right, probably a lot more wrong.

The other day Glenn came home, riffled through his mail and held a lacy heart-shaped object in his paw, wondering who had sent him a Valentine. Then he saw the scrawl. It wasn’t for him; it was for Pete. A gypsy girl made goo-goo eyes on the other side. “I’ll be your loving, wandering Valentine,” it read. “Guess who.”

Glenn mused. Well, this was what had come of giving in on dancing school. It wasn’t much of a family issue really. He just thought Pete was too young to get exposed to that school of social manners and dancing. But Ellie snorted, “He’s nothing of the sort. I’m not going to have my son grow up a tanglefoot like his father.” So he gave in. After all, Ellie had accomplished a thing or two in the dancing department and had a right to feel strongly on the subject. Glenn was thinking guiltily, too, that in all their married life they’d been dancing exactly twice—at Mocambo once, Ciro’s once. He’d walked around the floor those times, as usual. Never had learned to dance worth a nickel, since—wow, this was ’way back—his first public performance.

He was in first grade at Venice, California, right after they had moved down from Canada, and there was this May Day pageant. The teacher dreamed up a kiddie take-off on The Merry Widow. Because he had black hair that could be slicked down they picked him to play John Gilbert and that was great because the girl chosen for Mae Murray was a taffy-topped cutie named Elaine Shaeffer, his dream of dreams. But at rehearsal when he rapturously pranced out with Elaine the teacher said, “No, Glenn—no! I didn’t say ‘walk out’—I said ‘waltz out.’ ”

“I can’t dance,” he’d blurted.

“I can!” piped up a freckle-faced guy named Vernon, his arch rival for Elaine. So Vernon waltzed dreamily in the spotlight while Glenn sulked in the corner of the big production, ignominiously dressed as a clown and feeling every inch the part. Maybe Ellie was right at that. But now look. Girls!

“Hey, Pete,” he called a little later. “Uh-how do you get along with the girls?”

“Okay, I guess. Why?”

There might be a way to stall this off a little longer. “The way to handle girls, Pal,” said the voice of experience, “is to play hard to get. Keep aloof, pay them no mind. They love it.”

Pete nodded without much reaction and Glenn forgot the whole thing. Just what followed he’s not quite. sure. But at Miss Ryan’s Pete is the beau of the ball, a snap dancer who has the girls fluttering around him like butterflies, including such cuties as Van Johnson’s daughter, Ann Sothern’s, and Pete’s special throb, Edgar Bergen’s Melisse. What his dad would like to know (but doesn’t dare ask him) is, did he follow the advice, or didn’t he? Glenn has evidence—less happy to be sure—about another word of wisdom concerning manly affairs he passed on.

He’d noticed unmistakable signs when Pete came home from school—ripped shirts, scuffed knuckles, scratches here and there and once the beginnings of a black eye. He’d seen Pete right at home wrestling around with this and that kid. “He’s turning into a little roughneck,” concluded Glenn. “Got to stop this.” Again a memory bulb lit up. His coach at Madison School in Santa Monica had a system. When kids tangled in the schoolyard he drew a ring, put them inside and made them fight it out. Glenn had been in that ring only once. That was because of an argument with a much bigger kid, and miraculously he’d been able to dust him off. After that, he noticed, nobody picked on him and life was a breeze.

“Look Pete,” he counseled. “I don’t care how many fights you get into but there’s just one rule: See that you always pick a bigger guy than yourself to mix with.”

Pete stopped brushing his hair and struggling with his tie. “Why?” he inquired in amazement.

“Because,” said Glenn, “it creates respect. Now, at this party you’re going to this afternoon—when you walk in look around for the biggest boy there. If there’s any trouble make it with him. From then on your problems will be over.”

About a half hour later the phone rang. A highly indignant hostess shrilled in his ear, “Mr. Ford, I’m sorry, but you’d better come get Pete. He has just created a terrible disturbance.”

So Pete was in the car, mussed up again and chewing his lip. “I didn’t do anything wrong—just what you told me to, Daddy.”

“What was that?”

“Why, like you said. Right off I picked out the biggest guy there and I told him, ‘I can lick you.’ ”

“What happened?”

“He knocked me f-flat on my ear!” sputtered his son.

And I knocked you out of a party, Glenn groaned to himself.

The trouble is, Glenn realizes at such anguished moments, that you forget your words are literal gospel. Before you pop off, you’ve got to stop and think, “I’m this little guy’s hero. He thinks I wrote the book.” And since you didn’t and can still learn a lot yourself—why, this hero role is the roughest ever. That’s how it seems to Glenn, and he’s played plenty of other hero roles for the cameras (done all right, too) which is another thing that turns a black hair grey for Glenn as Pete sheds his kidhood and looks around.

Since the day Pete was born Glenn has been hipped on one thing: Pete was going to have a normal American boyhood, just as he’d had. There’d be no puffed-up movie star’s kid around his house. Not that Glenn Ford has anything against movie stars. He has enjoyed solid, satisfying success, collected a healthy bank account, interest in some oil wells and paper mills, and a devoted wife, Eleanor Powell, who was a very big screen star herself. Glenn and Ellie have been super wary from the start against spoiling Pete. They know how easy it is for an actor’s only son to get high falutin’ ideas.

Despite their comfortable station in life, Pete has never been pampered. He didn’t have nursemaids; he had his mother and dad to take care of him, busy as they were. Glenn even pitched all by himself once when Ellie went off to dance in London—and came back spurning five-figure paychecks and junking her career for keeps because, “It isn’t worth it to leave Pete.”

Glenn has kept the home atmosphere plain—even sometimes sternly severe. There’s still a rule that if Pete breaks a toy, he either fixes it himself or does without. He has had the responsibility of tidying his room since he was six. He earns his own Christmas money. Last year he came home with a flashy gilt compact for his mother, encrusted with glass diamonds and rubies. Ellie uses it and prizes it more than another she owns that’s the McCoy.

The only time Glenn indulged Pete was with the swimming pool, and in a way he earned it. When he was only six, Pete asked Glenn about that.

“Tell you what,” Glenn said. “When you can swim the length of the Beverly Hills Hotel pool, turn around without touching and swim back, you get your own pool.” Soon after, Pete took his dad down to the hotel and proved he could do it. So the pool went in.

For a long time Glenn managed to keep Pete in the dark about what he did for a living. When he’d go off to the studio it was just “on business.” But sometimes he had to rig up at home in high-heeled boots and a Stetson. Then he told Pete, “Got to go help a man with some horses.” Pete got the idea his pop was a ranch hand, which was okay with him. He was nuts about cowboys, and Glenn could remember when he had thought Tom Mix was a far greater man than the President of the United States. So he kicked the gag along. The only pictures he’d let Pete see were outdoor ones where he rode a horse. The first set he took Pete on was The Redhead And The Cowboy. Pete began to compare his dad with other two-gun heroes like Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry—and especially his TV favorite The Range Rider, Jock Mahoney. Glenn suspected that comparisons weren’t rating daddy so high.

So when he’d watch The Range Rider with Pete, and Jocko would pull a particularly death-defying feat, Glenn would scoff, “Ah, that’s easy. I can do it better than that.” Or if Pete admired a certain horse, he’d say, “My horse is twice as fast and smart.” But he got skeptical looks and sometimes a “Yeah?” And it began to get his goat. After all, Glenn is human.

The thing ate on him so that he collared Jock, whom he’s known for years and asked, “Do me a favor, will you?”

It wasn’t long after that seventy kids were whooping and tearing around the Ford home at Pete’s birthday party when the doorbell rang and there—wonder of wonders—was the Range Rider himself, pistols, fancy boots, buckskin shirt and all.

“Hello, hombre,” he greeted Pete. “Does a cowboy named Glenn Ford live here?”

“Yuh-yes, sir. He’s my father,” gasped Pete, as the seventy gaping revelers crowded around. “I’m his boy, Pete Ford.”

“Well, now, you’re a mighty lucky boy.” Jock played it to the hilt. “Matter of fact, I’ve come out here to thank your dad.”

“What for?” Pete tingled to his toes.

“What for?” boomed the great man. “Why, sonny, your father taught me everything I know. He’s the greatest cowboy of them all!”

Of course, such deceptions no longer work. A fourth grader at El Rodeo public school in Beverly Hills knows a thing or two. If he doesn’t, the kids tell him. So of course Pete came home one day with an awed and questioning look in his eyes.

“Dad, are you a movie star?”

“Don’t know about that,’ said Glenn. “Let’s say I make my living as an actor.”

“Gee,” Pete whistled. “I wanna be an actor, too, when I grow up.”

Well, there it was. Like father, like son. Was there ever a kid who didn’t want to be what his dad was? Glenn had wanted to be a railroad engineer just like his dad, and if the Fords had stayed in Quebec he might have been. What could you expect of a boy whose parents were both entertainers? He checked up. Yep, there it was in old Pete—the same imagination, which his dad had subconsciously stimulated from babyhood. All Glenn’s tall tales and poses were catching up on him. He didn’t tout Pete onto his spinach any more with tales of his friend Cecil, the seal, who lived under the house and brought it in especially for him to eat. He didn’t hide chewing gum in the magnolia tree and tell Pete it grew. there just for him. He didn’t make up a hair-raising bedtime story each night about his—Glenn’s—astounding prowess with rod, gun and wild-bucking broncos. He didn’t have to. Pete dreamed up better ones.

Last summer down in Brazil staying at a fazenda (like a ranch house) Pete knocked out a front tooth when, playing pool with another kid, a cue ball bounced up and smacked him. But what did he tell the gang when he came home? “See this tooth? I lost it in a fight with a panther. He clawed it out before I finally got him.” And right before his own dad too, without batting an eye. Where did Pete confidently announce he was going next with Glenn? The Fiji Islands, no less, and following that a tiger hunt on elephant back with the Maharajah of Hyderabad and then a big game safari in Kenya. And who had given him those ideas and someday would have to make them good? What had Ellie always said when Glenn racketed off on those location trips to Europe, North Africa, Yucatan? “Don’t worry about me. I’m never really lonesome when you go away. You see, I have two Glenns.” Umhm—and both with itchy feet.

“No, Pete,” Glenn said, “you don’t want to be an actor. Anything but an actor.”

“Why?”

“Well—” How could he tell his boy that the odds were too long, a million to one? How could he tell the kid who worshipped him that he, Glenn Ford, had made it only by the rarest luck? How could he say what he really felt, “I still don’t know how it happened to me. It’s still just playing cops and robbers.” But Pete liked to play cops and robbers, too.

“Oh, it’s a hard life,” Glenn lied. “Look, isn’t there something you’d rather do?”

“I like music. How much do musicians make?”

Too close. “Oh, not much. Two or three bucks a day,” he cut it way down.

“How about a doctor? I saw that bill on your desk—twenty-five dollars. Did the doctor get that just for looking at you?”

“Well—he has to know a lot to look at me.”

“How much do doctors make?”

“Forty or fifty thousand a year if they’re good.” Glenn built that one way up.

“I’m going to be a doctor,” decided Pete.

Glenn started to smile—but it wound up a frown. He’d talked Pete right into that. He felt a little ashamed of himself. What business was it of his what Pete wanted to do? What difference did it make whether he was a doctor, lawyer, plumber—or actor—so long as he was a good one and, more important, a good man? He’d find his way and in his own way. Pete is his son, but Pete is a person, too, part of a million other people stretching way back into time. The trouble with fathers like himself, Glenn decided, is that they overplay their parts—like ham actors.

You’ve got a son and you’ve got a second chance and that is both a privilege and a responsibility. But it’s no mandate to make over anyone in your own image, even if you could. That’s the danger of looking too closely and trying too hard. Sure, you die a thousand deaths trying to do the right thing, but the right thing is not steering him but backing him up. Funny, you worry about teaching Pete, and all the time he’s teaching you. What was it that poet wrote? “He doesn’t die who has a son.” Well, you don’t live unless you have one either, thought Glenn Ford.

“All that stuff’s a long way off, Pete,” he said. “Let’s see what’s for supper.”

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1954