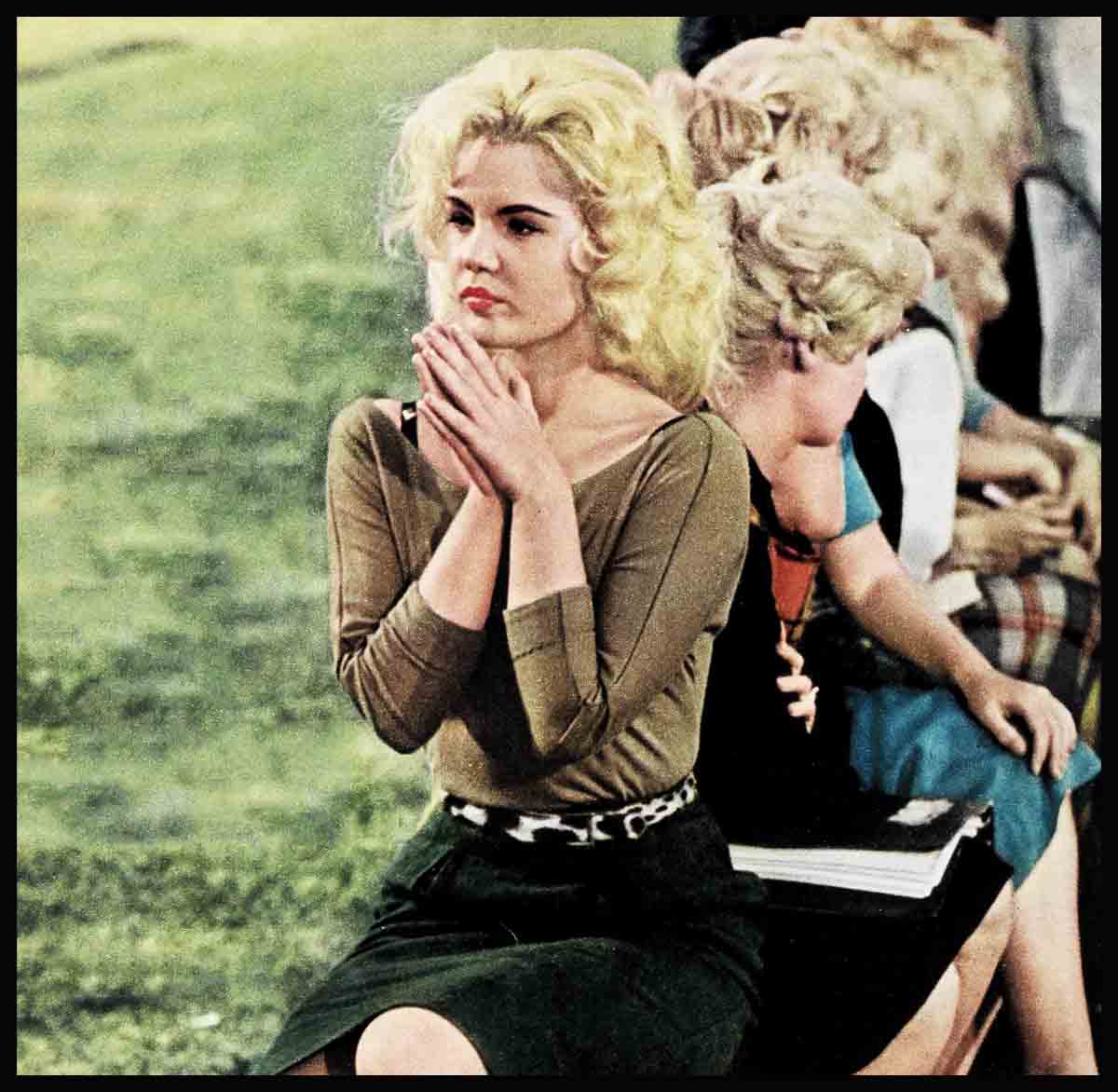

Tuesday Weld: “For Years, The Kids Wouldn’t Let Me Be Friends”

Almost all my life, I’ve been an outsider, desperately wanting to fit in but never quite able to make it. For as long as I can remember, there has always seemed to be barriers between me and other people. I was always standing on the edges of a crowd, so near I could reach out and touch them, yet never a part of them, because I didn’t have their price of admission—conformity. I was always considered different. Nobody took the time to really know me. Nobody sensed my longing for acceptance, the frustration, the hurt.

I began to create a world of my own. In this world, I could pretend that I was happy, loved, warm, secure, untroubled.

I guess the main reason for the things that happened, all started when I was three. My father died. We had no money left, and the four of us, Mother, my sister Sally, my brother David and me, had to live in a tenement building on the lower East Side of New York. My mother had to go to work to support us, and when I was three, I went to work, too, as a model. I had pretty dresses and shiny patent leather shoes and a warm coat and a handbag and a pair of tiny white gloves. I had to look nice when Mother took me on the rounds of agencies and advertisers, department stores and magazine offices. Everything I earned, that was left over from our bare living expense, was spent on clothes. I was poor, like the other kids, only I didn’t look it!

So the other kids would gang up on me and tease me. The boys would crowd around, push me and tear the black ribbon bows off my shiny Mary Janes. They used to follow me down the street, yelling things. I couldn’t understand why—I was just like them. Many times, on purpose, I’d rub dirt on myself and run outside and stand there hoping they would ask me to play. Sometimes they did. I was good at playing games that required make-believe. One of the favorite games of the girls, on the block, was playing movie star and, when they let me play, I was so happy I really put on a performance. I’d be Mrs. Cary Grant and we’d pretend we had just come home from some fancy party. I’d make up talk as I went along, and the others would follow me. It was wonderful, while it lasted, but as soon as the game was over they would leave me alone.

School was worse

When I started school, things got even worse. In the first grade, the kids in class used to tease me and call me teacher’s pet. I wasn’t. It’s just that I had permission to be absent when I got a modeling job, but he kids thought this meant the teacher liked me better.

When I was eight, we moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I started going to public school and made my family promise they wouldn’t tell anybody I had been a model. But I was still an outsider. I entered a fifth-grade class where everybody knew everybody but me. Besides, I’d been in and out of school so much, going on modeling assignments, that I hadn’t been able to learn as much as other kids my age. When I had to get up in front of the class to read, it was torture. I’d stumble over the simplest words, and everybody would laugh.

I kept looking for a way to belong. Most of the girls in my class were Brownies, so I joined the troop. I called myself a Brownie but I wasn’t one, really. We used to get together and cook things, only I didn’t know how. I’d never been taught. They laughed at my clumsy attempts until, one day, I ran home from a meeting and never went back.

When I was nine, something happened which set me further apart from the rest of the kids my age. Before, it had been my clothes. Now it was a case of Mother Nature playing games—I put on weight, my skin broke out in those red bumps that other kids don’t get till they’re 13 or 14. I was a mess—a real mess. I never knew, till a few months ago, but my mother had noticed this change coming on and that was one of the reasons why she had taken me away from New York.

The turning point

I was ten and a half when we went back to live on the lower East Side, in the very same tenement we’d left two years before.

I registered with the model agency, again, but I could tell they weren’t too anxious to have me. They kept sending me out on jobs but I was always too heavy, or too short, or too tall, or too something or other. I began to feel even more miserable.

But I kept making the rounds. A year went by and my skin cleared up and my figure lost its fat lumpiness. I looked at least fifteen—or so I thought.

I joined a little-theater group and met lots of people with whom I had things in common. We all had a desire to act or be, in some way, in show business. I met this group a few months before my twelfth birthday. I was determined that, this time, nothing would stop me from being accepted, so I decided to tell them I was sixteen. They were all older and I knew they wouldn’t want a 12-year-old around.

I began to wear heavy make-up, piled my hair on top of my head, put on high heels and tight skirts. I changed myself on the outside in order to be like the rest of the group. Kids my own age didn’t seem to like me, so I tried to find acceptance in an older world.

This was a turning point in my life. I began to live a lie. I began to deceive everyone I met, pretending to be something I wasn’t. By this time, we had been able to afford to move from the old neighborhood, so I could have had some of my friends over without being ashamed of my home. But I never did. I was afraid they’d meet my family and find out I wasn’t all I said I was.

I felt my real life was dull and un-interesting, so I began making up stories about myself. I told people I had been born in England, that I lived half the year with my family in a swanky apartment, and the rest of the year I had my own place. I told them I was going abroad. That I had been to Europe lots of times, and still found it fascinating. You can’t imagine the stories I told and, miraculously, my new friends believed me. They liked me. I was “in.” Everyone listened to me as long as I had interesting things to say, so I kept making up more and more lies until I was in so deep, I just couldn’t get out. It finally got to the point where I had to buy a notebook and write down all the things I told people, so I wouldn’t forget.

Besides wearing lots of make-up and older clothes, I looked for affectations I thought would help me seem even older. I started to smoke. I hated it. I literally forced myself to light a cigarette and puff nonchalantly. And somehow I even convinced myself that I was really like the imaginary girl I had created. I know, now, I was just a lonely, desperate child trying too hard to belong.

The road to unhappiness

Two years passed. I was in the thick of things; running around with a group of people, most of whom were twice my age. My work was coming along well. I had a little bit of success and I lived from day to day, suppressing any thoughts of the tomorrows. I had no idea that I had started down a road that would lead me to tremendous unhappiness.

In April of 1958, a few months before my fifteenth birthday, I arrived in Hollywood. All we could afford was a tiny cubbyhole of an apartment. Then, as I began to get work, we’d keep moving around from one place to another until it seemed that every time I finished unpacking, we were out looking for another apartment.

I didn’t know a soul in town. All I did was work, come home and feel depressed. In California, it isn’t easy to get places unless you have a car. In New York, I could hop on the subway or catch a bus and be with friends, but not now.

The first person I met out here, was Tab Hunter. I tried to act very sophisticated when I was with him and I had no idea he’d found out my real age, because this was before all the publicity began. He took me to my very first premiere. When we got there, we were interviewed. The man didn’t know me, so Tab introduced me and the man asked me to tell a little bit about myself. “How old are you?” he asked. I smiled and said, “I’m eighteen” without batting an eyelash. When we walked away, Tab said, “Oh, Tuesday, you know you’re only fourteen, so why don’t you admit it? You should be proud to be so young and have accomplished so much.” (That’s what my mother kept telling me but, at that time, I couldn’t see it that way.) I was so embarrassed, I started an argument with Tab and told him that I really was eighteen and that he had been misinformed!

Tab was pretty busy so I didn’t see him too often. Somehow, I drifted in with a crowd that resembled, at least on the surface, the one I had left in New York. They were all on the fringes of show business in one way or another. From the beginning, they seemed to like me. I guess they’re what’s considered a “wild” group. But, at the time, I couldn’t see it. If it hadn’t been for them, I’d have been alone. I found them fascinating, too. They used to talk about acting and philosophy, and about all their big plans. I didn’t know they were lying, anymore than they knew I was lying to them about some things in my past. I didn’t realize it then, but we were all pretty much mixed up for one reason or another.

My mother thought if I enrolled in high school and met kids of my own age, it would help me. I didn’t think it would, but I was willing to try. I enrolled at Hollywood High. It was a disaster!

The first day of school, I had an appointment for a job interview at 4 o’clock. I had to be all dressed up and since school wasn’t over until 3:15, I knew I wouldn’t have time to go home and change. So, I went to school dressed in “business” clothes—a black sheath, high heels and stockings. My hair was piled on top of my head, I wore make-up and carried my books and more make-up in a big black tote bag. I also wore black gloves, which were not only part of the outfit, but which also made it easier to carry the heavy tote bag.

When I walked into my first class, I could feel every eye on me. Then they began to whisper. I wanted to sink through the floor. Between classes, when I walked down the hall, kids turned to stare. They pointed at me and some began teasing and saying awful things. I couldn’t imagine why or what I had done. That afternoon, one of the teachers called me up after class and told me to remove my gloves, that my outfit was bad enough but that sitting in class with gloves was causing a big disturbance. I had started out in the morning wearing gloves and for some reason I had kept them on during class without even being aware of it. But when I was criticized for something I considered harmless, I had to fight back. When the teacher asked me why I wore gloves, I took a deep breath and told her I had to wear them because I had a contagious rash on my hands; that if I removed them, the whole school would catch my disease! She asked me what kind of disease I had. I told her it was called lacore and that I had picked it up in Mexico. Of course, I’d never even been to Mexico and, as far as I knew, there was no such word but, by this time, I didn’t care what I said!

I stayed at that school for a week. Naturally, once I’d made up my story, I was stuck with it, so I wore the black gloves every day. I also decided to dress as I pleased and wore heels, my hair up and clothes usually reserved for business appointments. The kids kept staring and the teachers kept picking on me, telling me I was creating a disturbance. One of them finally told me she didn’t believe I had a rash and to take off the gloves immediately. I refused. The principal sent for me. She told me I was not to come to school anymore in such a get-up, that it wasn’t right. Then she asked me why I couldn’t be like everybody else. Inside, my stomach felt like a butter churn. I wanted to cry out and tell her I’d been trying to find out the answer to that question since I’d been a child. Instead, I just looked at her and said I couldn’t be like everyone else because I was me. It turned into a real mess. When I walked down the halls, I felt as if I were the target for mass hatred. I had gone there hoping they’d like me, wanting to belong—but I couldn’t. I still didn’t understand why the other kids wouldn’t let me be friends.

Fortunately, I was able to leave and go to school at the studio. I was the only pupil in the 20th school, until Fabian came out to make a picture. I didn’t care about being alone in a classroom. It was heaven after what I’d been through!

Her worst enemy

Then the publicity started. Everytime I read something about me that wasn’t true, it hurt me inside. I got to the point where I felt that if people were going to write such things about me and hurt me, then I’d go ahead and do just what I wanted to, even if some of the things I did were “kookie.” I thought, by doing this, I would show them I didn’t care, but actually all I did was hurt myself.

Then I made “Because They’re Young” at Columbia; I was doing lots of TV shows and had a running part in the “Dobie Gillis” TV series. I didn’t have any time off, but the work turned out to be a blessing in disguise. After a day of school and work, I’d be too tired to want to go out. I began staying home more and more.

Home, was now a two-level house that we owned. For the first time in my life, I had roots—a place where I really belonged. I began to examine myself, and I discovered I didn’t always have to be running away.

I still went out with the group, occasionally, but now, after I’d been with them an hour or so, I’d start asking myself what I was doing there. I never had a good answer, so I’d get up and leave.

I began picking up hobbies and reading more. I enrolled in a modern dance class and began teaching myself the flute. Now that I had my own car, I sometimes took drives alone and just quietly thought about life and me and all the important things. I finally learned to discipline myself, and I’ve begun trying to find out what I’m really like.

I learned I’d been my own worst enemy. I discovered that I could have fun with people my own age; with people like Fabian and Dick Beymer. And I suddenly accepted the fact that I was sixteen—not eighteen, or twenty-five.

Ever since I made this discovery, life has suddenly become much easier for me. Even my relationship with my mother has changed. Before, I defied her—just as I did everything else—now, I no longer look upon her as an adult who doesn’t understand me.

Today, I think I’m on the right track. I still have quite a way to go and every once in a while, I find myself starting to go back to some of my old ways, only now I understand why and I’m able to stop myself. There’s one more problem to be solved, though.

I want desperately for people to know the truth about me. I want them to know what I’m really like and how I feel about things. I want them to know I am working hard to improve as an actress, and as a human being. I want to be liked and accepted for my talent and not looked upon as just a personality continually making offbeat news. I’ve done things that I wouldn’t do again if I had it to do all over, but I’ve never, never done anything or said anything to hurt anyone but myself. That’s what I want people to believe.

I hope it’s not too late for me to be accepted. I leave it up to you!

THE END

—by TUESDAY WELD (as told to MARCIA BORIE)

WATCH FOR TUESDAY WELD IN 20TH’S “HIGH TIME,” COL.’S “BECAUSE THEY’RE YOUNG” AND U.I.’S “THE PRIVATE LIVES OF ADAM AND EVE.” SEE TUESDAY AS SHE APPEARS ON CBS-TV, TUES- DAYS, 8:30-9 P.M. EDT., IN “THE MANY OVES OF OBIE GILLIS.” YOULL LOVE IT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1960