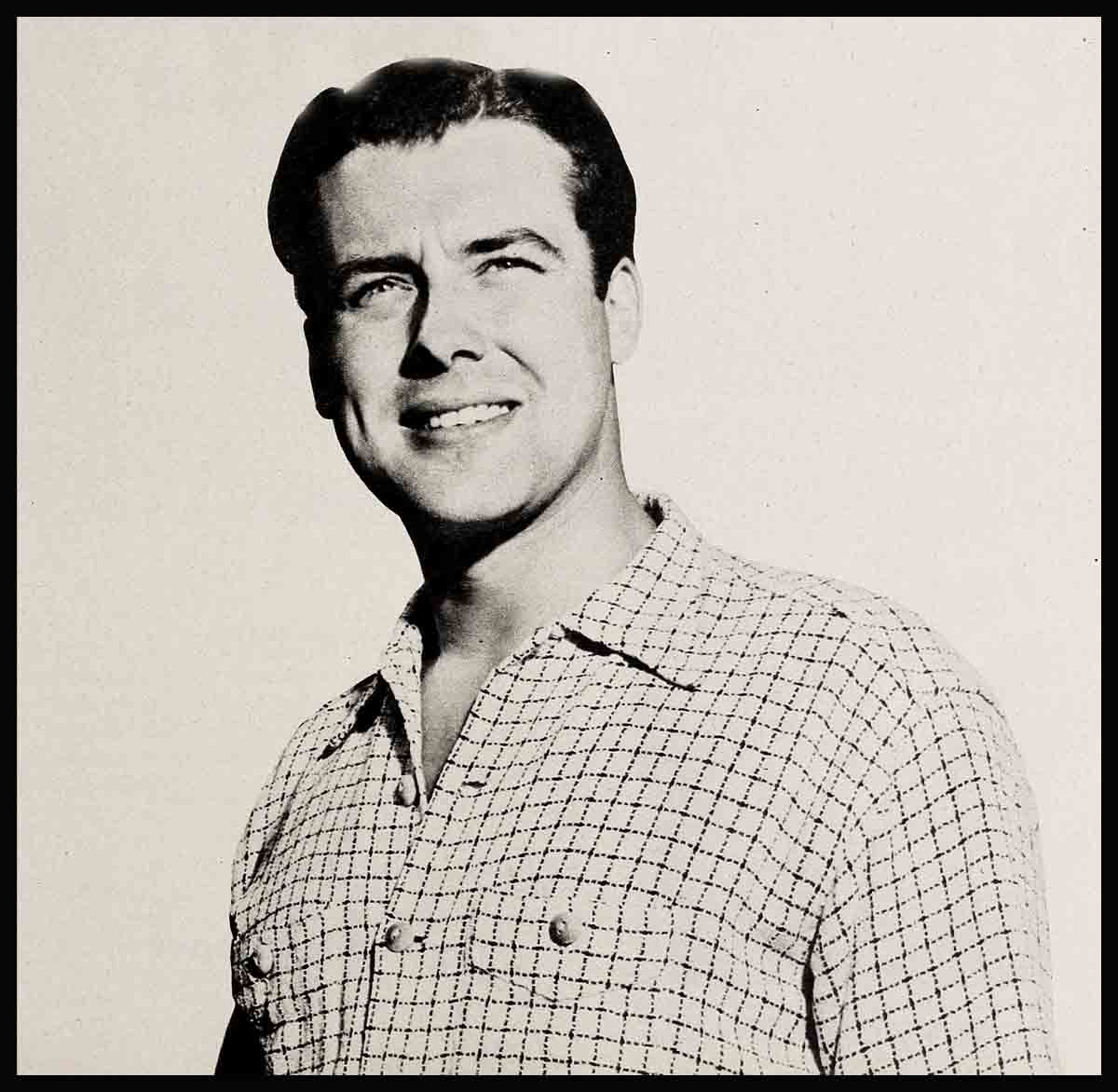

The Years Between—Richard Greene

You couldn’t even have called it dawn, really. The sun was just a shallow gold rim at the edge of the horizon and the English country road was grey in the half-light. But the young man peddling along on his bicycle whistled as cheerfully as if it were high noon. His name was Richard Greene, he was a lieutenant in the Royal Armored Corps, and—having looked in vain for a place to live in town—he was trying to find a room in the country for the most beautiful girl in the world—his wife.

He came to a pleasant looking stone farmhouse set in a grove of budding maples. Dick got off his bicycle and surveyed the place thoughtfully. It looked nice, all right.

He walked slowly up the path and around the house. He knew better than to try the front door of a farmhouse. From the thatched barn came the moo of a cow, and a dozen baby chicks crowded around Dick’s feet. Behind them strode a gaunt woman, with an icicle gaze and a red, weatherbeaten face.

“I beg your pardon,” he said feebly. “I—I’m looking for a room for my wife. We’ve been married since Christmas Eve. I’m stationed over at the camp three miles from here, and I thought—I mean this looked like such a nice place, the kind Pat would like—but of course I don’t blame you at all.” He finished, breathless.

“Now, now, slow down, young man. How much were you thinking of paying?”

“I hadn’t thought, actually. Whatever you say.”

The farmer’s wife muttered something under her breath. It sounded like “a fool and his money are soon parted.” But fifteen minutes later Dick was peddling triumphantly to town.

Back at the barracks, Dick took a goodnatured ribbing. “Easy for a matinee idol like you,” the boys said. “I think I’ll try telling the next old hag I ask that I’m Clark Gable!”

left his career behind . . .

Actually, of course, it a never occurred to Dick to mention that he was the Richard Greene who had made pictures in both England and America before the war. His career had been successful, certainly, but he had put it behind him when, in September, 1940, he left Hollywood, to go home and enlist in the British Army.

Some of his friends told him then that he was crazy. “You’ve got a bad leg from that car accident you were in a while ago. Use that for an alibi, and stick right here. America isn’t at war, and you’re just going good. You’ll make a fortune.”

“It wouldn’t be enough to buy back my self-respect,” Dick had said quietly. “I don’t like war any better than the next man, but England’s my country.”

He enlisted as a private in the ranks of the 27th Lancers. Promotions came, but slowly, as they do in the British Army. Then the leg injury he had suffered in Hollywood was aggravated by an added strain during training.

“Sorry, Greene,” his superior officer told him. “No combat duty for you, after this injury. Your leg wouldn’t take it. You’re eligible for medical discharge now, if you like,” the officer went on briskly. “Or you can stay in the Army and do non-combat work. There’s plenty of it to be done.”

Dick was silent for a moment. A discharge would mean that he could go back to Hollywood and take up where he’d left off. Probably the money he could make and contribute to the British cause would help a lot more than the non-combat work he could do. Damn it all, he hadn’t sacrificed his career and come over here and gone through training just to sit the war out at a desk!

That mood lasted about ten seconds, then Dick grinned. “I’d like to stay in the Army, sir.”

He wondered a little as he said it, what Pat would think. Because by now he was married to Pat Medina. She was half-Spanish and half-English. He had met her late in 1941 when he was given a temporary release from the Army to make a propaganda picture at Denham.

One day Dick was strolling across the set of another picture they were making there. He noticed a beautiful girl talking to the director. Soft black hair to her shoulders, smooth peach-colored skin and lively dark eyes.

“Not bad,” he said to the friend with him. “Not bad at all.”

The friend laughed. “Our national genius for understatement. That’s Pat Medina and she’s not only beautiful, she’s a good actress.”

“Know her, do you?” Dick asked, very, very casually.

“As it happens, I do. Come to dinner at my place Thursday, night and you can talk to her all evening.”

Thursday night came, and at the party Dick sat down by Pat who was looking chic, cool and detached in a black dress that flowed smoothly around every curve.

“A bit silly to talk shop so violently, isn’t it?” he offered, as the babble of the other guests’ voices rose and fell around them.

Pat pounced on that like a puppy on a bone. “What’s silly about it? We make a living out of acting. Why shouldn’t we talk about it?”

Dick swallowed. “Sorry,” he said. In a moment he made an excuse to get over to the other side of the room. The girl was beautiful all right, but what a disposition!

So that was that, and Dick forgot about it. But a couple of weeks later Dick was in London for the weekend. On the street ahead of him some GI’s whistled appreciatively at a girl crossing Trafalgar Square. A girl with smoky black hair and tawny skin. A girl named Pat Medina.

Dick found himself walking faster and faster. Not that he really wanted to see her, of course. And not, he thought wryly, that it would do him any good if he did. She obviously hadn’t thought much of him. Still, she might be willing to have a drink.

Fifteen minutes later, over sherry, they were both wondering how they could have been so wrong. Pat was wonderful. She bubbled like champagne, with a dry wit and delightful charm.

“You certainly didn’t like me the other evening when we met,” Dick said eventually. “What did I do wrong?”

an explanation . . .

Pat explained. “When I got to the party everyone was having a fearful row, and I felt left out with no one to argue with. Then you came in so I started on you, thinking it was the thing to do. Only you wouldn’t argue, you just went away.”

Dick laughed. “We seem to have made a botch of things, between us. Let’s make up for it by having dinner together tonight.”

So they went to Dick’s favorite restaurant, but since it was London in war-time they had to “queue up” for a table. By the time they got one, an hour later, they were in love. By the time they’d had dinner, they were engaged. On Christmas Eve they were married in a ceremony that left out all the pomp and circumstance but left in all the beauty and solemnity.

There couldn’t be any honeymoon. Dick’s picture was finished and he was back in the Army. But they had three days together in London. Three days to catch up on all the things they wanted to know about each other. To recall and compare their childhood Christmases, when they had never dreamed that any Christmas could be as wonderful as this. To make love, and argue, and make love again. Three days to be happier than any two people had ever been before.

Then Dick had to join his regiment in Yorkshire, while Pat waited in London. But now he had found this bedroom in the old stone farmhouse, and Pat was arriving tomorrow, and life would be heaven again.

He had one awful moment of misgiving when she stepped off the train. She looked so elegant, so completely out of place among the dumpy country women who followed her. What was he doing, bringing a girl like Pat to live on a farm, with nothing to do but wait for him to come out from camp?

He needn’t have worried. The minute he kissed her, he knew somehow that everything would work out. That as long as they were together, nothing else would matter to either of them.

And Pat in slacks and a sweater, with her hair blowing in the wind as she cycled along a country lane, bore little resemblance to the svelt, bored actress he had first met. She was happy and carefree and her sense of humor carried her over the rough spots.

“Our landlady doesn’t approve of me,” she confided to Dick. “I’m sure she doesn’t believe we’re really married. She said ‘What do you expect me to call you?’ and when I said ‘Mrs. Greene’ she positively sneered!”

“She has a heart of gold under that sneer,” Dick assured her, laughing. “And I’ll bring out our marriage certificate and put it on the mantel over the fireplace.”

That fireplace was their delight. They sat in front of it during the long evenings, reading, talking, holding hands. It was all very romantic—until eleven P. M. Then the farmer’s wife would come in and make the same little speech every night.

“If anyone wants to use the ‘conveniences,’ they’d better do it now before I lock up.”

The “conveniences” was her euphemistic term for the outside plumbing.

One day Dick came downstairs in the morning looking very preoccupied.

“I just remembered that they’re showing Kitty Foyle at camp tonight,” he told Pat. “They’ve never shown a picture I was in before, and I’m terrified. Suppose the men hiss!”

Pat howled with laughter. “I think it would be too funny,” she said unfeelingly. “A new sort of mutiny—one you couldn’t do a thing about, Lieutenant Greene. I must come to the picture.”

“Don’t you dare! It will be quite awkward enough, without that.”

But at eight o’clock there was Pat, in a scarlet coat that made her look like a young gypsy queen, her eyes dancing with mischief. They sat together in the back row, while Kitty Foyle unrolled and Dick squirmed.

embarrassing moment . . .

There was a general turning of heads when he first appeared on the screen. Dick wondered gloomily if any of the four generations. of acting Greenes who had preceded him had had to cope with any situation like this. He thought back to the previous most embarrassing moment of his life. It was when he played his first stage role, that of a spear-carrier. Dick had decided really to make a production of that spear-carrying. He had leaned against the wall, started an animated, if silent, conversation with another spear-carrier, and made gestures like Barrymore playing Hamlet. He had visions of the director calling him over after the performance and saying “No more walk-ons for you, Greene. From now on you’ll have good parts.” The director called him over, all right. He said “Greene, you’re fired!”

But this experience was even worse. Dick dragged Pat away before the picture was over. He worried all night. Suppose when he gave orders the next day, the men just laughed! They didn’t, of course. In fact, some of them said “Very good picture last night, sir.” Dick felt better.

That was why he was delighted when, in 1943, he was offered a chance to tour France, England and Belgium with an Army company of Arms And The Man. Pat was in it, too, which made everything wonderful.

In December of 1944, Dick was given a medical discharge by the Army. Less than a year later he and Pat were in Hollywood where Dick was to make Forever Amber.

They came over on a Liberty ship. The weather was bad and the trip took far longer than they had expected. Pat says she spent all her time on deck alone, singing “Sentimental Journey.” Dick was busily playing poker with the GIs on board—and winning. Some months later he went into 21 in New York and the captain who showed him to a table was one of the men he had won it from.

“I couldn’t afford to play with him now,” Dick says, grinning.

forever delay . . .

The first few months in Hollywood he was terribly restless. Everything seemed to conspire to delay the shooting on Forever Amber. Dick was one of the few members of the original cast retained when they started all over again. Twentieth had originally suggested that he should play Carlton, the man Amber really loves throughout the picture. But he himself felt he was better suited to Almsbury, Carlton’s friend, and that was the role he eventually played.

At last Amber began really to roll, and Dick was happy again. It was good to be back before the cameras, making a big picture. Even the beard he had to wear didn’t bother him—much.

But Amber was over, eventually, and the restlessness set in again. Dick had agreed with his studio that he wouldn’t make any quickies which might beat Amber out as to release date, since they’d all figured his first post-war appearance should be something flashy.

So he went home and sat. He knew he was going to do Britannia Mews, at some point during the next year, but the point seemed far-off, and if it hadn’t been for the new house, he couldn’t have stood the inactivity.

The new house took a lot of thought, and a lot of time. It’s in Coldwater Canyon (Beverly Hills) and it’s two-story Georgian. It’s set back off the street about sixty feet, surrounded by privet hedge, and it has a small pool on the front lawn.

Pat did a couple of pictures while Richard fidgeted—Moss Rose, and Foxes of Harrow—both loan-outs to Fox from Metro, where she’s under contract.

She’d come home at night, and Dick would sigh. “Fine thing. My wife rushing off to work every day, while I hang around and worry about how three men lay the green carpeting, and the way they’ve remodeling the wood-work upstairs.”

“You’re an idiot,” she’d say briskly. “Amber’ll be out any day now, and then—”

The small brown Pomeranian called “Amber” would wander in at this point, and hearing herself named, would act foolish and ingratiating, and what could Dick do but laugh?

“I guess I’m a crank,” he’d say. “Don’t know when I’m well off.”

Now Amber’s been released and the period of waiting’s over. It’s just a question of what comes next. The Greenes discuss this, evenings.

“Maybe a play,” Dick says. “A New York play—but serious, not a comedy—”

And the way his eyes light up, his wife could cry. Because here is a guy who loves to work, and gets excited by the prospect, and there’s something so marvelously eager about him that he can’t help communicating the excitement.

But they’re British, so they don’t talk emotionally. Pat simply says, “A play would be lovely,” and her eyes say all the rest.

THE END

—BY VIRGINIA WILSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948