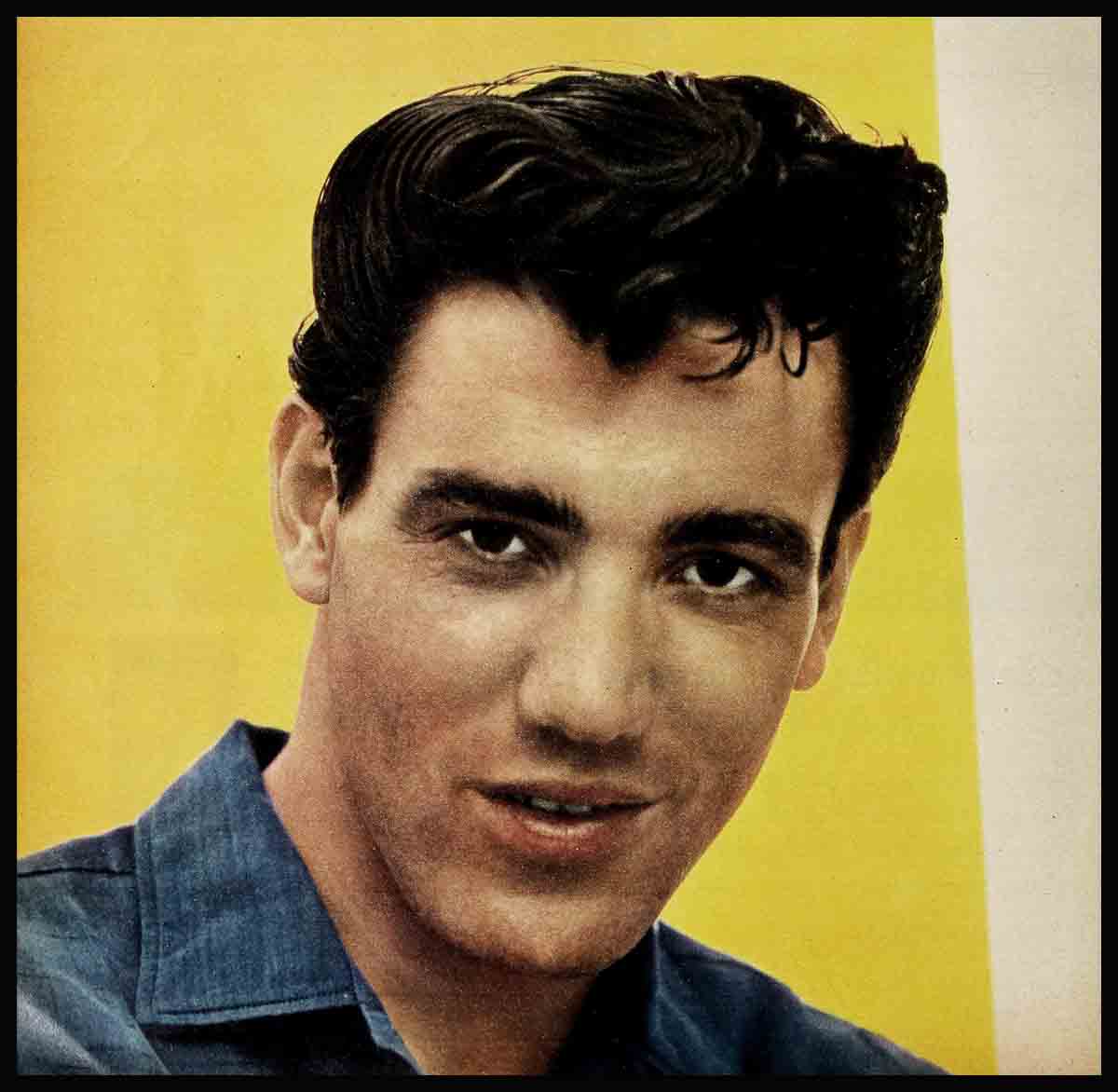

The Complete Life Story Of Jimmy Rodgers

One gray afternoon—barely a year ago—a slim, dark-eyed fellow named Jimmy Rodgers stopped his beat-up convertible before a dinky cottage in a rundown part of Hollywood. He switched off the radio, lit a cigarette and slumped down behind the wheel to think. He had some news for his wife Colleen inside, but he didn’t know quite how to tell her.

Colleen was just out of the hospital and still too weak to walk. There wasn’t any food in the house, unpaid bills cluttered the table and about everything Jimmy had, including his car, was hocked.

Six months had passed since he brought his bride and his guitar to Hollywood hunting a break as a singer. All Jimmy wanted to do was sing, but a married man had to face facts: he hadn’t made it.

Jimmy braced his sagging shoulders, pushed back his rebellious black hair, pulled up the corners of his mouth and went inside.

“Well, honey,” he began bravely, “Looks like I’ve finally got myself a job.”

“Where, Jimmy?”

“Why—uh—,” he stalled. “It’s just for a while, understand—until we get on our feet. That Standard service station up the street. He says if I come in Monday—” “No,” she checked him.

“Look, Colleen,” he blurted desperately. “It’s either that or the papermill back home!”

“Never! Jimmie, I married a singer and a good singer. That’s what you’re going to do. We’ll just hang on,” she stated firmly. “Something’s going to happen. . . .”

That same week something did. Jimmie Rodgers was called to New York to make a trial record. It was Honeycomb. Before a month was out he was famous and on his way. Today Jimmie has three more hits and a best-selling album. His bookings stretch from here to eternity. He’s been on every big TV show that counts. He has a movie contract at MGM. This year, Jimmie will make over $200,000—and that’s just the beginning.

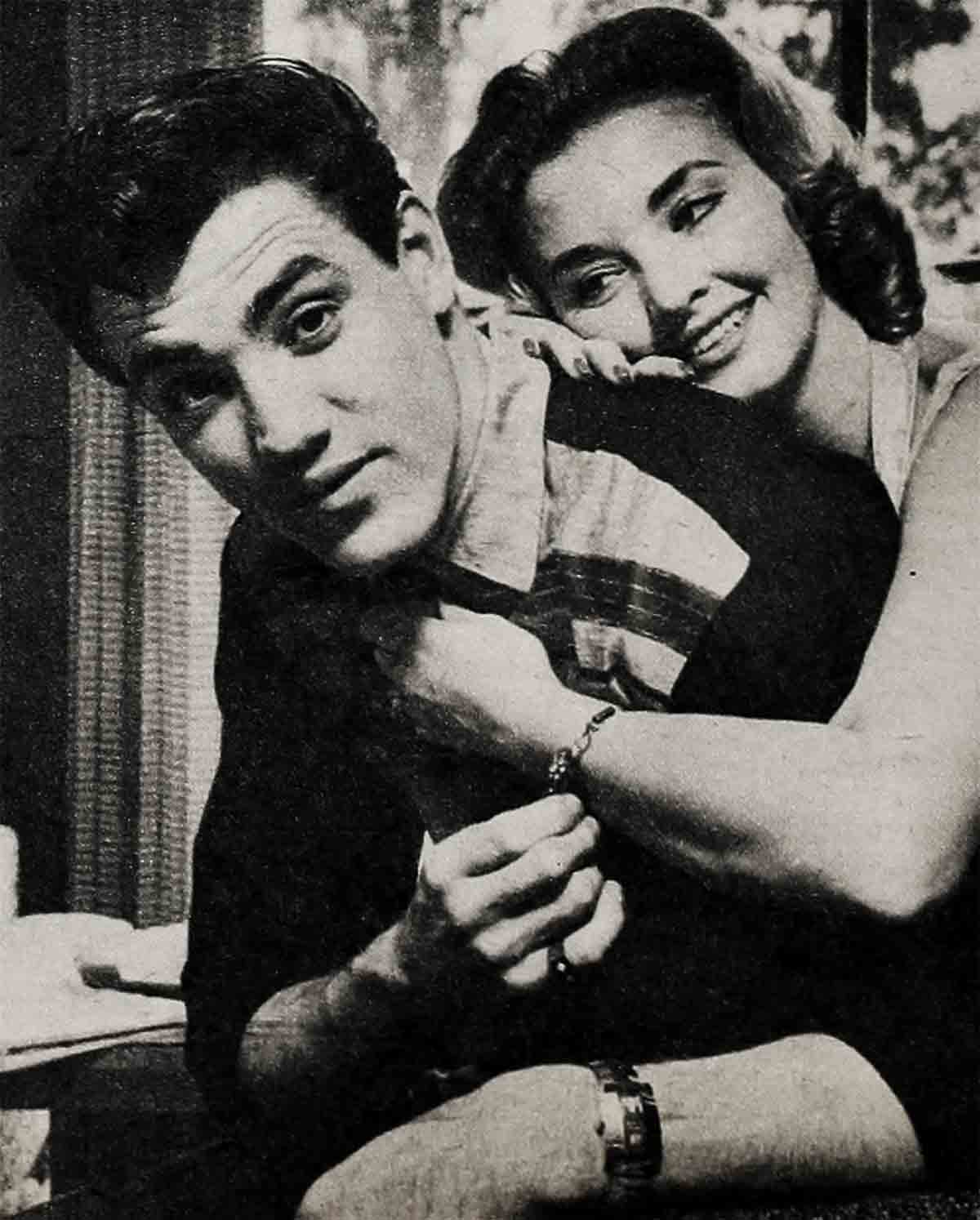

Jimmie and Colleen’s story is one of true love, faith and plain, old fashioned devotion.

Because, when Colleen courageously bolstered the belief in himself that was beginning to waver in Jimmie Rodgers, she was only paying him back in kind. Two years before, when Colleen desperately needed reassurance, hope and love, Jimmie was there.

That was after the foggy night when Washington state patrolmen lifted her out of a smoking wreck on a highway. In the broadside crash, Colleen’s ribs were broken, her spine twisted and some internal organs ruptured. Worst of all was her face. It was smashed almost beyond recognition.

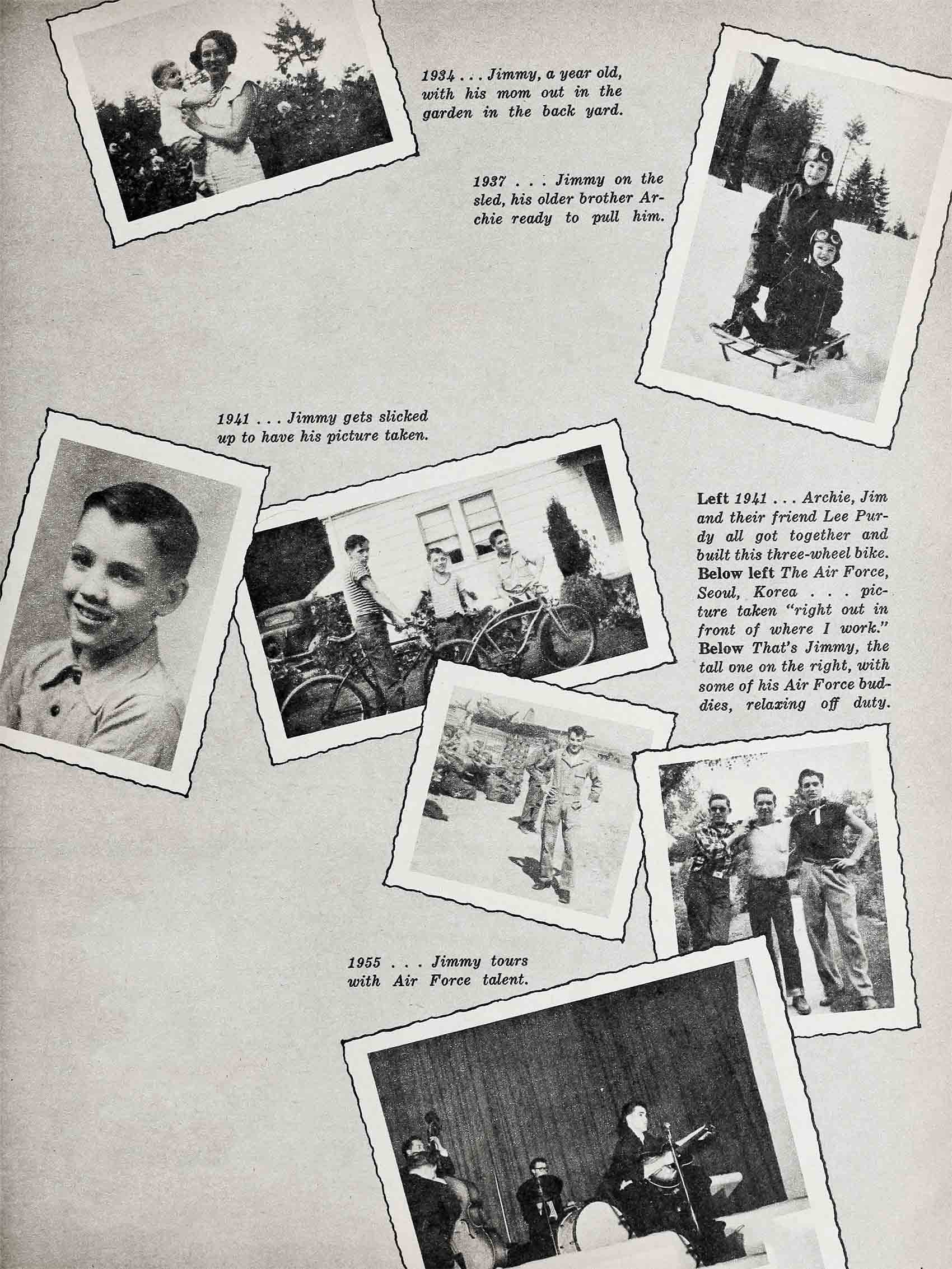

1937 . . . Jimmy on the sled, his older brother Archie ready to pull him.

1941 . . . Jimmy gets slicked up to have his picture taken.

1941 . . . Archie, Jim and their friend Lee Purdy all got together and built this three-wheel bike.

1941 . . . The Air Force, Seoul, Korea .. . picture taken “right out in front of where I work.”

1941 . . . That’s Jimmy, the tall one on the right, with some of his Air Force buddies, relaxing off duty.

1955 . . . Jimmy tours with Air Force talent.

Unwanted

The highway tragedy was especially sickening. Colleen was the prettiest girl in Camas. In fact, she was so beautiful that Hollywood had already discovered and made her a starlet with a bright future. She was on a visit home when the accident occurred and, ironically, was to return to Hollywood the next morning. Hollywood would never want her again.

But Jimmie Rodgers did. He wanted her more than ever. And forever.

Jimmie wasn’t with Colleen that tragic night. But he had been two nights before. He’d taken her into Portland, Oregon, sung to her until dawn and confided his hopes and dreams. When he took her home he had given her his heart—and Jimmie doesn’t give that lightly. Although he was past twenty-one, Colleen was the first girl, and, from then on, the only one. To Jimmie, her beauty wasn’t only skin deep.

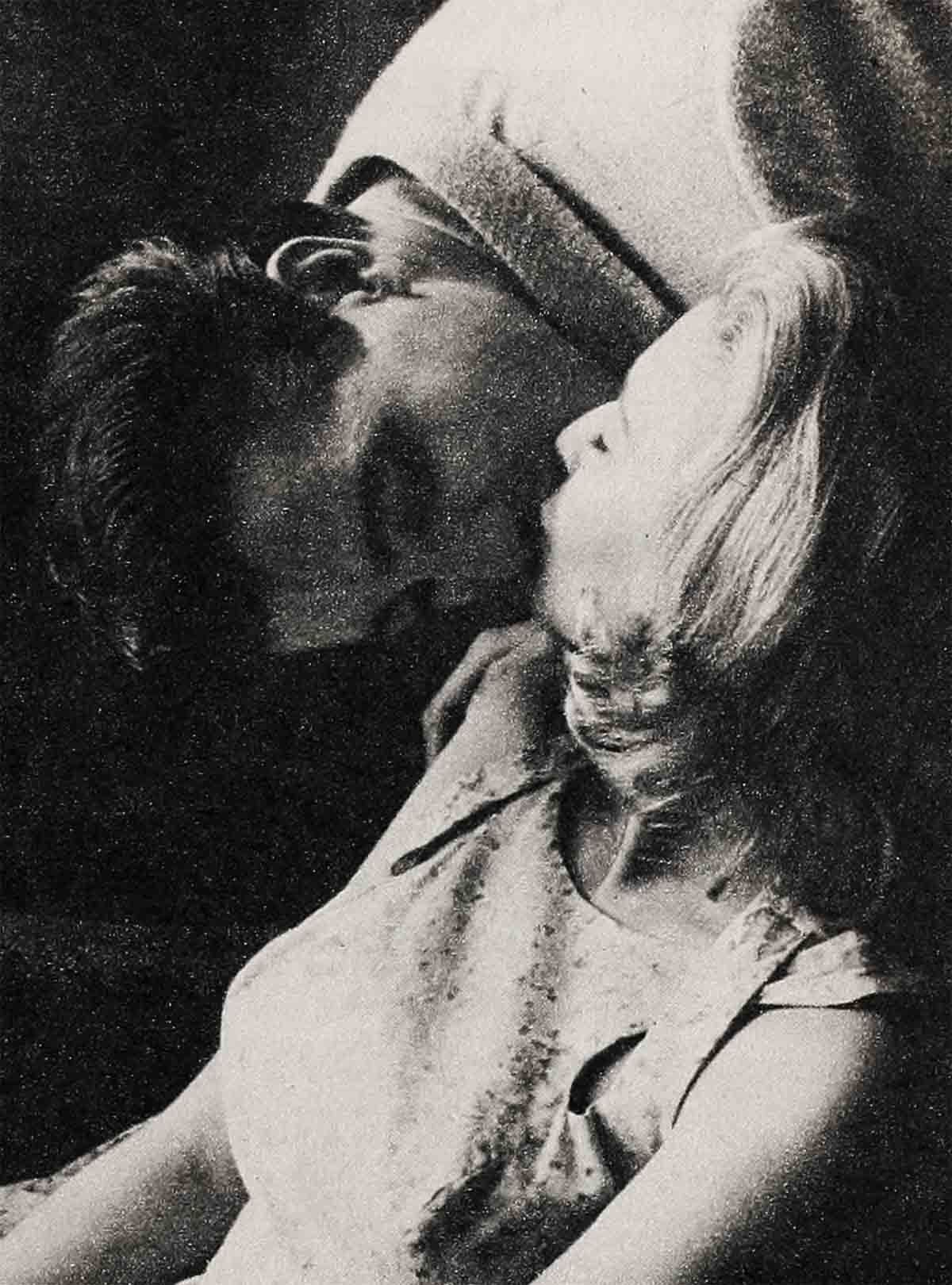

For a year, as surgeons worked to restore Colleen’s health and her face, Jimmie courted her in the hospital. Most of that time she was wrapped in bandages, with a plastic mask covering her shattered features. Seldom could she even walk. But in her pain and in her shock, Colleen could still give what Jimmie Rodgers had to have—encouragement and inspiration. In that year, with her urging, Jimmie made his start as a singer, developed his style and won his spurs. When Colleen was strong enough, he married her and they came to Hollywood.

By now, the miracle of modern plastic surgery had brought back much of Colleen’s beauty, just as the success Colleen inspired has restored Jimmie’s belief in himself and his future.

When Jimmie Rodgers sings, I’m Just A Country Boy, it’s no mere lyric. The country is bred in his bone, blood and fibre. It comes out in Jimmie’s clear, unpretentious voice, his raw-boned good looks, gentle, soft spoken manner and his uncomplicated values and virtues. Right is right with Jimmie, and wrong is wrong. Anger is anger, love is love and loyalty, loyalty. No sophisticated frills clutter him or his thinking—and he’s not likely to collect them. Jimmie has been just himself from the time he was born in the timber country of Washington, September 18, 1933. His folks came from pioneer stock.

Jimmie’s granddad, on his mother’s side, fought with Teddy Roosevelt in the Rough Riders and, after that, drove cattle in Texas. Jimmie’s mother, Mary Elizabeth Shick, was born on a ranch and is part Cherokee Indian. Brought to a Washington farm as a little girl, she sat in a one-room schoolhouse next to a sturdy boy named Archie Rodgers, whose forefathers had hit the Oregon Trail West. When she turned eighteen she married him. James Frederick was their second son, although they’d hoped for a girl to balance the family. Maybe it was just as well that he was another boy.

Depression days

Because things were rough with Mary and Archie Rodgers then. The Depression was bumping rock bottom, and Archie eked out a living working for the CCC. Later when things picked up, he hired on at the big Crown-Zellerbach plant in Camas. He still works there, and so do Jimmie’s mother and his big brother, Archie, Jr., four years older. When he was big enough Jimmie worked there, too. It was back to that mill that his thoughts turned in desperation a year ago in Hollywood.

The first home Jimmie Rodgers remembers is a dingy paint-flaked shack in Tidland Heights, out towards the woods from Camas. He had to toddle outside in the freezing winters to the privy and, on Saturday nights, his mom heated kettles on a pot-bellied stove, then poured hissing streams into a galvanized tub on the kitchen floor. She scrubbed Archie and Jimmie together, once a week, whether they needed it or not. Jimmie was a fat little guy until the big ice storm when he was four. Then he contracted double pneumonia and almost died.

That night the doctor couldn’t walk up the steep, slick path to their lonesome house. He crawled up on hands and knees, and Jimmie remembers the ice-crusted bag he opened before bending over his tight, wheezing chest with the stethoscope. The doctor stayed all that night and all the next day until the crisis passed. He couldn’t take Jimmie to the hospital; there wasn’t any, anyway.

After that, Jimmie Rodgers dropped his baby fat and seemed to stop growing. All his boyhood he stayed runty. Jimmie weighed only 99 pounds as a sophomore in High School and today, although he pushes six feet, he fights to keep 140, gulping malteds with raw eggs almost every time he turns around. It’s just a fix with him now, but back then it was a real problem. “I hated being a runt,” remembers Jimmie. “So I did everything I could to prove I was as good as any other kid.” Mostly, where he lived, that meant a scrap.

Little tough guy

Jimmie’s long, string-pickin’ fingers are still crooked from the times he busted them flailing out for his honor. He had his head split open four times. His cheeks were chronically striped with cuts and his eyes framed with purple shiners. He didn’t always fight fair and didn’t feel bound to. “If a big kid—even Archie—was beating me up, I grabbed a club or a rock and let him have it,” admits Jimmie. “I wasn’t fighting for fun.”

By now he can control the flash temper, but as a kid what he chronically saw was red.

Jimmie’s mortal enemy was a German boy named Alvin—bigger, of course—who lived across a field. They were constantly engaged in bloody combat. “I guess I developed my voice,” allows Jimmie, “yelling insults at Alvin from my back porch. He cussed me back in German, and I never figured that was exactly fair.” Stealthily at night he’d raid Alvin’s yard for his toys. Next day, he’d find his mother’s flower garden stomped. And that really hurt.

His mom’s gladioli were the only dependable asset the Rodgers boys had until they became men. Glads were Mary Rodgers’ specialty. In the rich soil and moist Northwest climate she grew giant stalks of every variety. Archie and Jimmie worked the year round in the beds. In the fall they’d dig the precious bulbs, husk and divide, tag and store them and then replant that winter. When summer brought the crop of gorgeous blossoms, they’d pack them in a wagon and pull it to Camas. On street corners the flowers went fast at fifty cents a bunch. Sometimes between them Jimmie and Archie would collect $100 a summer—and that meant their clothes for school.

Money was always scarce, it seemed, around the Rodgers’ house, even though everybody worked. When Jimmie’s dad came home from the paper mill, his mother left for the night shift in the bag factory. “I wish I had a penny for every meal I’ve cooked and dishes I’ve washed,” smiles Jimmie. “I’d be rich.”

Still, it wasn’t all drudgery and Jimmie looks back on his boyhood with a special fondness. His country was a kid’s paradise. All around him tall pines pierced the sky, deer bounded, rabbits scurried and quail whirred away with heart-stopping surprise. Jimmie could hike in the summer days to Lacamas Lake or Dead Lake to fish for trout, bass and perch. The swimming was great in Sandy River.

You ask Jimmie Rodgers when he first began singing and he can’t rightly remember. “Why, I guess I’ve been singing all my life,” he says, a little surprised at the question. It’s almost the truth. Music and song were as much a part of the Rodgers family daily fare as food.

Mary Rodgers played the piano and sang with a silvery voice. Jimmie’s father liked to sing, too, and even Archie. They gathered around the piano after dinner and on Sunday afternoons to sing the old sings that Western people love. In a way it was their only home entertainment. There was no TV then, of course, and half the time the battered radio was out of action. As soon as he could wobble to his feet, Jimmie joined the group, piping first a song his mother taught him:

There must be little Cupids in the briny.

There must be little Cupids in the sea. . . .

In first grade at Forest Home School, Miss Schimmelpfennig, the teacher, used to crook her finger. “Jimmie Rodgers,” she’d say, “The kindergarten children are about ready for their naps. Come here and sing them to sleep.”

Jimmie never had to be urged. He’d sit down by his wriggling wards and happily croon Danny Boy or Let the Rest of the World Go By until they fell asleep peacefully. Pretty soon Mrs. Inez Russell, the music teacher, was taking him over as her special project. It got so that every youth singing group in town had Jimmie Rodgers out front, leading with his cool, clear boy soprano. He was a regular in the Christian Church school choir every Sunday.

Oddly enough, the other guys never razzed Jimmie about his singing. Because what Jimmie sang were the songs they’d heard from their fathers, mothers and grandparents, and when he sang them it was like waving a state flag.

Singing wasn’t all he could do, of course. Jimmie was good in his studies. He caught Archie—who’d been sick a year and flunked twice—in sixth grade. Later, they graduated from Camas High in the same class. Reed thin but wiry, Jimmie still was a fair country athlete, too. He played top basketball, football and starred on the tennis team.

Jimmy drew a blank

In romance, though, Jimmie Rodgers drew a blank. He never had a date all through high school. At dances he’d sing to the girls but he didn’t dance with them. Why? “Well,” explains Jim, “I didn’t have a car, I didn’t have any money, I didn’t have time and I didn’t have a girl I cared for.” Funny part was, Jimmie had already met the girl who was to mean more in his life than anyone ever could. But he certainly didn’t suspect it then.

He was playing one afternoon with the Pollack brothers, in their barn out in the country, riding the plough horses, when the little girl down the road came over and made herself a pest. Colleen McClatchey was her name, and she was as Irish as it was. “A blonde, blue-eyed, freckle-faced monster,” was how Jimmie first remembers Colleen. They tried to shoo her away but she stuck like gum. Finally, to get rid of her, they tied her to a tree and told her they were going to burn her at the stake. All through Camas High Colleen McClatchey followed Jimmie three grades behind, and he never knew she existed. But there were plenty of things Jimmie Rodgers didn’t know about then.

Even when he graduated, at seventeen, Jimmie was as vague as the average teenager about what he’d do for a living. If you’d have told him that strumming a guitar and singing those old time songs would make him rich and famous he’d have called you crazy.

After high school, most guys around Camas counted on the paper mill for a living. Some joined the service, as Archie did, three days after graduation. Jimmie Rodgers did both, as things turned out, with an unhappy crack at college thrown in.

It might have been the Aaron Music Award he won on graduation day that made him try to swing a classical music education. Clark Junior College in Vancouver, thirteen miles away, had a good music department. So Jimmie worked that summer as fifth hand at the. Mill, bought a $200 Ford and that fall checked in at Clark. He left home at 7:00 in the morning, got out of school at 3:00 o’clock, drove home and took on his heavy mill chores from 5:00 to midnight. He lasted seven months before he was skin and bones and falling asleep in his classes. He thinks what made him finally figure what’s the use was his voice teacher’s verdict: “You’re wasting your time—you’ll never be a singer.” How could anyone arrive at that conclusion? It’s sort of funny—Jimmie’s voice didn’t change for keeps until late. In college, trying to sing exercises, he sounded like a mocking bird with the croup.

Jimmy joined the Air Force and was sent to Japan next with Supply, but it was so dull dishing out gear over a counter that he promoted a transfer to Korea. In Seoul, Combat Cargo Training kept him loading freight and passengers on planes, twelve hours a day. One GI passenger heading for home, proved to be a passenger for Jimmie.

He spotted him lugging a guitar bower the plane and swearing as the clumsy box banged his other baggage. Jimmie saw opportunity and grabbed it. He bought it for ten bucks.

Until then, Jimmie Rodgers hadn’t touched his pads to a string or sung a tune outside the shower. “I’d been too busy,” recalls Jimmie, learning a thousand things—including how to control my temper.” For hot-headed, independent Jimmie Rodgers, Service discipline wasn’t easy. Right off, in basic, he bumped another trainee on a stairway, and got a name he wouldn’t take. Jimmy knocked him headlong down the steps, bounded down after and stomped him—Indian fashion—right into the hospital. Don’t think Jimmie got off easy for that. But he mellowed. “I finally learned to count ten,” grins Jim.

Barracks jam

Now, with his ten-buck guitar he started fooling around with the old tunes again. Soon you couldn’t jam your way around his bunk at the barracks. A band called The Melodies was swinging things around the Officers’ Club, and rec halls, finally copping second prize in an all Korea barracks contest. Jimmie sang, of course, and tickled his guitar along with a piano, drums and fiddle.

Whenever he got lost in a song Jimmie Rodgers also got homesick. When Jimmie sings today, done out in a tux, at some big city spot like Hollywood’s Moulin Rouge, he’s really back in the timberlands of Washington. It was that way in Korea. And just about then he got a box of cookies and a note from a girl he knew at home, doing her bit for the boys overseas. “Hope you enjoy these, Jimmie,” she wrote. “Colleen McClachey helped bake them.” As Jimmie remembers, he got just two cookies out of the box in the scramble. But as he munched them he mused, “Colleen McClatchey—wonder how that kid turned out?”

It took Jimmie Rodgers some time to find out. He came back stateside July 4, 1954, and dropped by Camas on leave. Colleen was out of town. Jimmie Rodgers wound up his service hitch in Nashville, Tennessee, as base dispatcher loaded with the responsibility of as many as forty planes in the air at once. But he still found time to win the talent show and, in a national service contest at Langley Air Field took second. A female impersonator—of all things—beat Jimmie out for first prize. Still, that showing told Jimmie Rodgers part of what he wanted to know.

“At last, I knew what I was going to try to do when I got outside.” To prep himself he sang on week ends at the Club Unique in Nashville.

But then he went back home to Camas and started a ninety-day sweat. Inside that time he could take over his old job at the mill and not lose seniority. In the ‘same period of grace, he could re-enlist in the Air Force without losing his rank. “I tell you, I chewed some on that one,” says Jimmie. “I had just $200 saved up and I was past twenty-one. I guess I still didn’t believe that singing was really a man’s work.” Very soon he found out it surely was.

Jimmie also found out that Colleen was in Hollywood—with a contract at Universal-International. Audie Murphy, himself, had discovered her working in a Portland hospital. Jimmie eased out a low whistle when he heard that. “I guess that crazy freckle-nosed kid turned out all right,” he said.

One afternoon Jimmie dropped by McClatchey’s Cleaning Shop with a jacket. “How’s Colleen doing down in Hollywood, Mrs. McClatchey?” he asked.

“Just fine,” she told him. “But, she’s here now—right in back. Don’t you want to say ‘hello’?”

Jimmie said more than ‘hello’ when he saw Colleen. He blurted, “My goodness—how you’ve changed!” That night he took er out for a cup of coffee, then got an idea. How‘d you like to drive into Portland? There’s the swingin’est little band there that you ever want to hear!”

All night long

That was the night Jimmie Rogers still remembers as strictly a case of Cloud Nine. They went to the Yalta Club and stayed until 4:00 in the morning listening to the throbbing rhythms around them and, as far as Jimmie was concerned, to a deeper beat from inside himself. It was the first like that he’d ever felt. They went on to another all-night spot and wound up finally at 7:00. “I sang all night long,” sighs Jimmie in recollection. “I was in heaven.” He was also in love.

Next day Jimmie’s head hummed with melodies that his heart echoed. They told him two ringing truths: He’d never be happy in any other job but singing—and he’d never love another girl like he loved Colleen.

She’d promised Jimmie another date before she left. In between Jimmie went over to Seaside, Oregon, and into the Sandbar Club. He practically forced the hillbilly band there to let him sing, and he sang as he never had before—all night long. By morning he had a job at $65 a week. Jimmie called his folks with the news, but he made them promise not to tell Colleen McClatchey. He wanted to tell her that triumph himself, when he drove back for the date. But there wasn’t any date. When he came home Colleen was in the hospital. She’d almost made it safely home from a dance in Seattle—but not quite.

It was a poignant courtship those next few months for Jimmie Rodgers. “I knew Colleen wouldn’t want to see me or any of her friends,” he says. “So I stayed away. But I sent her notes and flowers and little gifts and I tried to be jolly and keep her spirits up.” Later on, when she could be moved, he took her out for drives into the country they both loved so much, even though it stabbed his heart to see her lovely face covered with bandages.

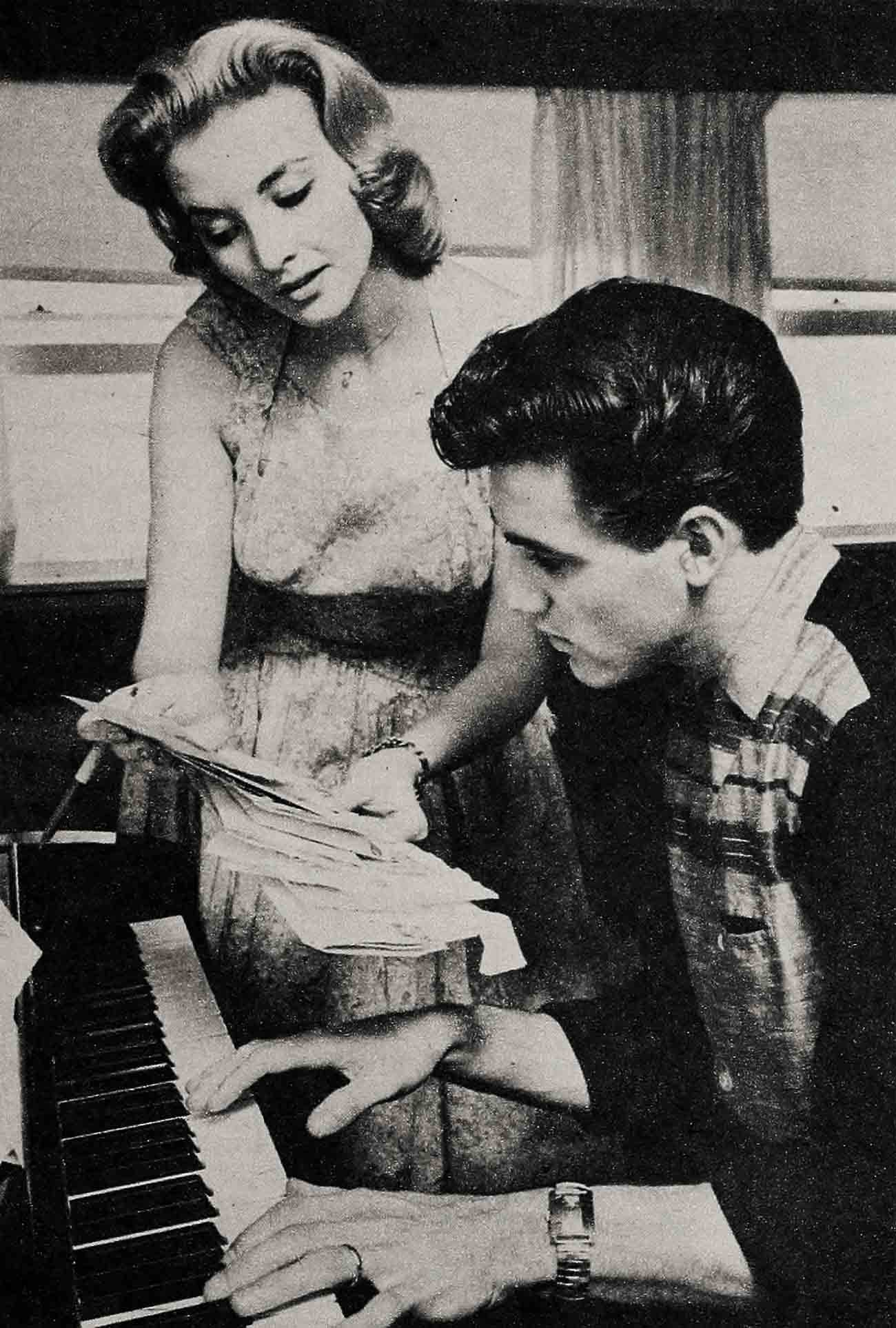

But if Jimmie worried secretly about her, Colleen didn’t. Her anxieties were about Jimmie Rodgers. Jimmie was still singing with the hillbillies at the Sandbar.

“You’re too good for hillbilly music,” she told him. “You ought to go on your own. You can make it. When I get out of here,” declared Colleen spunkily, “I want to see you doing a single—Jimmie Rodgers and his songs!” Before she was through with the hospital, Colleen got her wish. Although what she saw made her burst into tears.

One-man band

That was up in Wenatchee, Washington, at the Elks Club, where an agent in Portland booked Jimmie sight unseen at the fabulous figure of $150 a week. He’d driven up all by himself, excited and trembling with what he thought was the Big Break at last. The manager met him the minute he walked in. “Where’s the rest of the band?” he asked.

“What band? I’m a singer. me,” stated Rodgers.

“You mean,” exploded the boss, waving his hands wildly around the room, “you and that guitar are going to make all these people dance?—How?”

“I don’t know, Mister,” confessed Jimmie Rodgers. “But I’ll sure try.”

Jimmie junked the guitar at first, sat at the piano and sang. Nobody moved. Desperately, he yanked a chair out to the middle of the room, called for a spotlight, introduced himself and explained the mix-up. Then he sat down and went to work.

He mixed up the old songs with rock ’n’ roll, pop, hillbilly and what have you. But even to things like Danny Boyand Cool Water he gave a dance beat. When Jimmy had time to look up the dance floor was jumping. The manager came over and patted his back. “Son,” he said, “I don’t know how you did it, but it looks like you’re in.”

But Jimmy was more than just ‘in’ and earning his $150. That night, working forty-five minutes out of every hour, he hit on something new that has been Jimmy Rodgers’ trademark ever since. He became a ‘folk-swinger.’

All that week—as a one-man dance band—he packed them in. “People came just to see if it was true!” grins Jim. One who came—even though it was a big effort—was Colleen. She was still wearing a mask to fill out her face. That’s when she cried—not for herself, but for Jimmy.

His left wrist was raw from sliding up and down the guitar neck. His fingers were oozing blood. You can still see the scars.

After that, Jimmy Rodgers didn’t have any trouble finding a job in those parts. He went to the American Legion Club next, with a drummer to help carry the load. He broke all records there and at the Fort Cafe in Vancouver, Washington. People started coming from miles around. But Jimmy’s fairy godfather turned out to be right across the street.

Chuck Miller was a veteran song-and-piano man from the East. One night Chuck came over himself to hear Jimmy. The minute he heard Jimmy it was no longer a mystery. He knew talent and he recognized a new singing style.

Jimmy gets an angel

From then on Chuck Miller became Jimmy’s volunteer praise agent, advisor and financial agent, too. Back in New York Chuck talked up Jimmy and his style around the pop recording set he knew. Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, then with Mercury, were especially interested. So before long, Chuck Miller wired Jimmy $300 from his own pocket, with the message, HOP A PLANE, HONEYCOMB.

All the way back to New York the propellers seemed to drum that tune. When Chuck took him around the record offices, it was Honeycomb he sang for them. Later, of course, it became the tune that made Jimmy big. But not that trip.

“Well get hold of you later,” is what he got everywhere, but that didn’t cash out at the bank. Jimmy stayed nine days while Chuck staked him. Then he flew back to the Fort Cafe. A telegram was already there from Chuck, telling him to get down to Hollywood, if he could, and look up Chuck’s agents there. Maybe the Golden Gate for Jimmy was out West.

Jimmy bought that idea, but he had to settle something first. Those few days in New York away from Colleen had proved that without her he was nothing. He bought an engagement ring, took Colleen out for a drive and, at a stop sign, begged, “Here, Honey—put this on— please.” She did. They were married in a double-ring ceremony January 4, 1957, in Portland. At the time, Jimmy Rodgers’ fortune amounted to exactly five dollars. He worked at the club until he had $200 coming, then they drove to Hollywood.

Things looked all right at first. Jimmy hooked a job the first week at the Keyboard Club, and Chuck’s agent lined him up for a few TV guest spots. Then—nothing. But Colleen, hungry and sick as she was, said, “No—hang on. It’s coming.”

Call it a woman’s intuition, maybe. But even as she spoke, ‘it’ was already on the way. Back in New York, Hugo Peretti was frantically trying to locate Jimmy in Hollywood. He’d started his own Roulette record firm and wanted to tee off with a new singer. He remembered Honeycomb, but the bee had buzzed off. Nobody knew where Jimmy Rodgers was.

Of course, they finally tracked him, and that was a day Jimmy Rodgers won’t forget. “It was two o’clock in the afternoon,” he recalls. “And all morning it had been gray and foggy. But when that voice said, ‘We’re sending $300—can you come back and record Honeycomb’—I looked out the window. You know what? The sun was shining bright!”

He drove East with Colleen and, with his honey by his side, Jimmy didn’t have much trouble cutting Honeycomb. But there wasn’t any advance and toward the end they got down to dining on tootsie rolls and collecting coke bottles to cash in at the flea-bag hotel where they lived. Then a lucky $700 he made on the Arthur Godfrey Talent Scout show paid their bills and left enough to drive home on.

In North Platte, Nebraska, stopping with Colleen’s relatives, he got the verdict. “You’d better get set for a disk-jockey tour, Jimmy,” advised Hugo; “Honeycomb’s starting to move.” It moved, all right—clear on past the million mark.

“Ever since then,” grins Jimmy, “it’s been wonderful. And it’s been murder. . . .

The wonderful part, of course, has been Jimmy’s terrific success. “I love it, because I love to sing,” allows Jimmy, “I wouldn’t really be happy doing anything else. But it’s sure been no vacation.”

Jimmy hasn’t had a rest since the ball began. Most of his play dates have been one-nighters, so he’s been hopping all over the country like a flea, leaving one plane for the next, dressing out of a suitcase, getting along on six hours’ sleep, dropping pounds and collecting an ulcer. Whenever she can, Colleen travels with him, because, “I like to know she’s in the audience,” Jimmy Rodgers reveals. “She’s my good luck piece.”

Right now, the only family the Rodgers own are two toy poodles—Bivi, a white, one Colleen had before they married, and a black one, named Honeycomb, naturally. They’re camping in a small rented house perched above the Sunset Strip, with a black Thunderbird and a white Plymouth in the garage. But they aim to buy a bigger place and fix it up, “when the dust settles.”

The Rodgers haven’t been to one Hollywood shindig and that’s only half of it. Neither Jimmy nor Colleen dig the social bit in the slightest. In fact, about their only good friends among the entertainment set are Tommy Sands and Molly Bee. Sometimes, when there’s a breather, Jimmy takes Colleen dancing to the Cocoanut Grove. But, neither care about drinking. The other night some business friends dropped in and Jimmy hastily called his manager, Bill Loeb. “How do you make martinis?” he asked. Bill gave him the proper formula for gin and vermouth. “And you might drop in an olive or an onion,” he added.

The guests almost es Jimmy filled their drinks with chopped scallions!

“Actually, I don’t need much to make me happy,” says Jimmy Rodgers honestly. “I’m grateful for all the luxuries I never dreamed about that have come my way, of course. I want to keep on singing and have people like to hear me. I want a home someday near good hunting and fishing—maybe a boat to fool around with, too. I want some children, if we can have them. But mostly, I want to do as much for Colleen as she has done for me.”

In his pocket, Jimmy keeps a silver medallion and he wouldn’t think of singing a note without it. Colleen gave it to him when she married him. It’s engraved with the prayer, GUIDE MY DESTINY.

The face on the medal is that of St. Genesius, patron saint of entertainers. But to Jimmy Rodgers it’s the face of Colleen, the girl who has guided his destiny since he put it in her hands and, always will.

THE END

Jimmy is scheduled to be in MGM’s SNOB HILL.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1958