Junior Femme Fatale—Natalie Wood

The girl and the boy sat on the ground in deep concentration, a Scrabble board between them. After a while, the girl slowly pushed a group of letters into place.

“Are you sure that’s a word?” asked the boy.

“Of course I’m sure.” said the girl. “I know I’ve seen it somewhere.”

“I guess we should have brought a dictionary,” said the boy dubiously. “I’d like to see if it’s in there.”

“I wasn’t so certain about your last word, but I didn’t say anything,” the girl pointed out with feminine logic.

It was a typical conversation. It might have been a typical scene—two blue-jeaned figures on somebody’s front lawn, perhaps in Iowa. However, this girl wore an Indian costume and this boy was dressed as a cavalry officer, and they were in Monument Valley, Utah, which seemed closer to nowhere than almost anywhere else.

The hot sun was beating down and the girl put her hand to her sunburned arm.

“Hurt much?” the boy asked.

“Not much,” she grinned. “Not very much.”

Then they heard her name called. “They’re ready for you,” the boy said. “That’s what you get

for being a movie star. No time for Scrabble.”

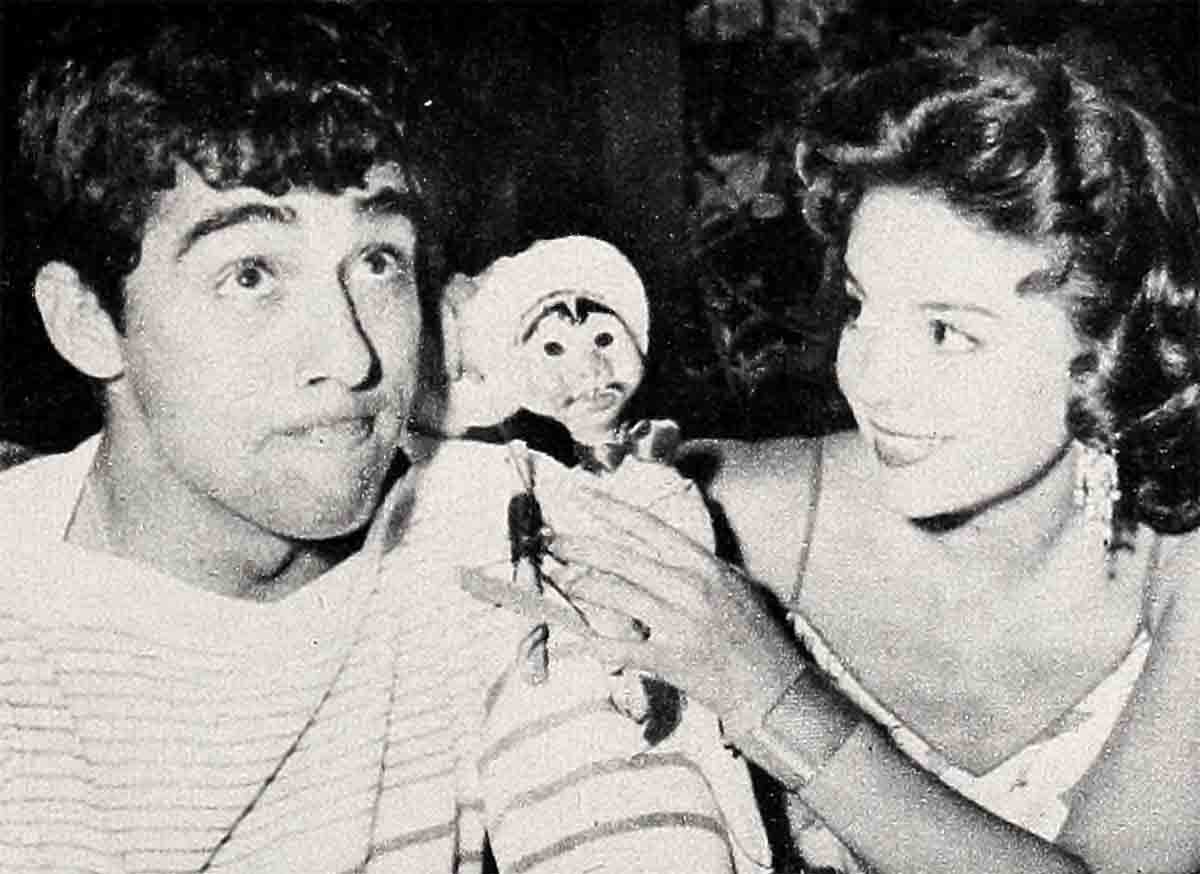

Natalie Wood laughed, got up and went toward the set. Pat Wayne picked up the Scrabble board, put away the pieces and followed to watch her do a scene for “The Searchers.” Despite his teasing, Pat was on the sidelines to see all of her scenes. “Because she’s such a good actress.”

Pat had been on location for a week by the time Natalie had arrived. She’d climbed out of the car and had seemed glad to be there. And he figured that when a girl had joggled a hundred and eighty miles over the tired dirt roads that led to Monument Valley—well, she had a right to temporary sunstroke.

Granted, there was a plain and peaceful beauty about the desert. But there was entirely too much peace for a teenager. Company nearer his own age would help, Pat had felt.

On some nights at the lonely trading- post location—when the day had been extra hot and the work had been extra hard—Natalie, her sister Lana, and their mother retired early and fell into bed from exhaustion.

Other nights, however, Natalie and Pat took turns diving into the post dictionary and exchanging “I told you so’s” and “I’m sorry’s.”

There was no place to go, no sights to see, nothing to do. When playing Scrabble grew boring, gin rummy set in. The two teenagers, missing their usual rounds of social activities, reached the mutual conclusion that things were pretty dead. “Another thing you get for being a movie star.”

“If a good part goes with it, I’ll take it.” Natalie was putting it mildly. Come desert, sun and sandstorms, or the quiet of Monument Valley, she wouldn’t give up her career for the world. She couldn’t, because it is her world.

A comparative newcomer, Pat’s a rising young star who is just beginning to learn the acting trade. Natalie has been concentrating upon her career since the time it was only a dream to her. Even as an infant her talents couldn’t be checked. When she was a mere three months, she got into the habit of howling at night, and her mother and father took turns getting up and rocking her. Then, one early morn, her father hit upon the idea of humming to his wailing daughter. This proved successful—until Natalie was four months old and began humming back.

She was three when her dream of a career began. Each morning, she would borrow finery from her mother’s wardrobe and totter toward the garage on high, reluctant heels. If asked, however, she would have told you that she was on her way to the world’s largest motion picture studio, where the world’s greatest pictures were being made.

Inside the garage was a desk, long banished from the house. Approaching it, little Miss Wood would stop for a moment to mull her daily problem. Then, having made her decision, she’d announce it to the desk. “This morning I’m Bette Davis.” It was a difficult choice, but she was comforted by the fact that after lunch and a nap she could always return and be Lana Turner or Sonja Henie. And when she grew up. . . .

A year and approximately a half-inch later, Natalie, then Natasha Gurdin, was on her way. That was the year 20th Century-Fox made a picture called “Happy Land” and sent a location troupe to Santa Rosa, California, where the Gurdins were living.

Looking over the crowd of local sightseers one morning, director Irving Pichel glanced down and discovered a pair of large brown eyes squarely meeting his own. On the pixie face was a button of a nose and a smile that was something to behold. “Hello there,” he called. “Come talk to me.”

Natalie came running, climbed onto his lap and immediately began the conversation. When she stopped to catch her breath, Pichel inquired if she could also sing. “Oh, yes,” she replied. “I listen to the radio and know a lot of songs.” She was singing one of them for him when her mother found her.

Pichel gave Natalie a small part in the picture to see how she would react to the lights and cameras. Her chore, he explained, was to drop an ice cream cone and burst into tears. It was then that Natalie chose to be a realist in her make-believe world. “That’s nothing to cry about,” she told him. “Mother can always buy me another one.”

Then she added helpfully, “But I’ll cry if you want me to.” After which she dropped the ice cream cone and wept her heart out.

When the picture ended, Pichel promised to send for her when the right part came along. For two years he wrote letters of encouragement while Natalie waited. She was six when he suggested that the family come to Hollywood, for their daughter surely had a future in movies.

The Gurdins debated the move. Could Natalie be an actress and still have a normal childhood? Could she, as an actress, grow up to lead a normal life as an adult?

The familiar image of a child star is a frightening one and, in some cases, rather accurate. The movie moppet, many claim, is a pint-sized princess in the lavish scheme of Hollywood royalty and comes to know it far too soon. She fights for good roles rather than toys and learns to steal scenes instead of cookies. She goes wading in her own private pool and when it rains she can always stay inside and walk barefoot over her little ermine jacket.

She grows up in a world of worshipping adults and grows too fast, yet somehow never quite enough. She forsakes her kiddie car for a Cadillac, and public school is the building where she drops by to pick up her high school diploma, after years of semi-private tutoring.

She’s constantly surrounded but, nevertheless, in the midst of a crowd she’s aware of being apart from it. A wage-earner since she recited her first lines, she longs to declare her independence, and an early marriage is the most logical means of breaking parental ties.

At an age where most young people are selecting vocations, hustling off for higher educations, or breathing the first whiff of orange blossoms, the former movie moppet may be stepping into a divorce court to tell a tale of marital failure. For the movie child, too often, life is just a bowl of mixed emotions.

Realizing all these things could happen to Natalie, the Gurdins faced a difficult decision. But if, by chance, this was the rule, they vowed that they would raise an exception. And so they went to Hollywood.

Natalie was given the role of a German girl in “Tomorrow Is Forever.” She first signed a contract with Universal-International, then with 20th Century-Fox. Following this, she free-lanced. “Wherever she worked,” says Mrs. Gurdin, “I made it a point to ask people not to praise her too much or treat her as a motion-picture star. And the same held true at home.”

Today Natalie, herself, points out, “I was in the very fortunate position of being a child actress, not a child star. I had all of the benefits and none of the drawbacks.”

There were lessons to be learned along the way. One of the most memorable was on temperament. In one of her pictures, Natalie was to make each of her appearances with a puppy in her arms. Now if there is anyone more adept at scene-stealing than a child, it’s a dog, and the leading lady was quick to recognize the double threat. “I will not have that child in a scene with me,” she raged and promptly had Natalie and her canine friend written out of half the script.

Natalie took it philosophically. “When I grow up,” she assured the puppy, “I’m always going to be kind to child actors and dogs.”

When she was eleven, Natalie was signed for “The Star.” “It was while working with Bette Davis that I realized there was more to acting than being in pictures and reading your lines,” she says. “I discovered that the best way to learn was to study the people with whom I was working—the directors, the stars. It’s not so much what they say as what they do.

“I learned that the main thing is truth. You have to ask yourself, ‘Is what I’m doing real? Is it what the person I’m portraying would do?’ If it isn’t, it’s superficial. You can be criticized for a lot of things, but not for giving an honest performance,” she concludes.

“Natalie has always had a very professional attitude toward her career,” says Nicholas Ray who directed her in “Rebel Without a Cause.” “To keep a sense of balance and a sense of unity is difficult when you’re alternating between the fantasy world of pictures and the realities of everyday living. Natalie has had to do this and she’s done it well. Older and stronger and more experienced people have cracked from trying.”

When she wasn’t working, Natalie attended regular school, in addition to being tutored on the studio lot. “I missed out on many of the problems in school, where boys and girls are undecided as to what they want to do,” she says. “I knew what I was going to do. It was a matter of studying and working toward that goal.”

Natalie admits that, when she enrolled in Van Nuys Junior High, she got off to a grim public school beginning. Having previously skipped a grade, she was younger than the other students in her class, and she arrived bedecked in ruffles and pigtails. The girls looked down at her from their well-heeled heights, straightened their tight, tight skirts and applied another coat of lipstick. Obviously, said their manner, the newcomer was an infant.

Natalie rushed home sobbing. “Mother, we’ve got to go shopping. I just can’t wear these clothes any more.”

She convinced her parents that a tight skirt was a necessity, but her father was against any lipstick. After a lengthy discussion, they compromised on a pale pink shade which she faithfully wore at home Occasionally, however, when she came from school, her mother would notice traces of bright red on her lips.

During those years, Natalie went to parties and dances, acquired new friends by the dozens and now and then allowed other members of the household the use of the family telephone. Every so often she’d announce that she was having a slumber party. Mrs. Gurdin will never forget the time Natalie forgot to pas: along the information and twenty-five girls showed up with blankets and pillows. “They threw them on the floor and slept there,” Mrs. Gurdin recalls. “I didn’t mind. We had a larger house at the time there was plenty of room, and we got used to the noise.”

Although she has her share of girlfriends Natalie has admittedly preferred the company of boys since an early age. This preference may stem from an unhappy experience at the age of five when she and another neighborhood siren vied for the affections of one Douglas Olsen, also age five.

Douglas was an obliging beau who willingly divided his time between Natalie and her rival, Renee. The girls, however, held a dim view of his impartiality. Whenever Douglas played with Renee, Natalie would swing into action. She’d call his mother. “Mrs. Olsen, will you please have Douglas come right home and then send him over to play with me?” she’d request.

Renee’s campaign was somewhat less devious. One afternoon while Douglas was sharing the back-yard swing with Natalie, the lady being scorned picked up a stone and took aim. The next fellow Natalie saw was the doctor, who examined the lump on her aching head.

But all was forgiven when Douglas asked Natalie for an honest-to-goodness date. She demanded a formal gown for the occasion, got it, and accompanied Douglas and his mother to dinner and a show.

These days, Natalie prefers to go out with actors. Perry Lopez, Nick Adams, Raymond Burr, to name a few. And Tab Hunter is a favorite date, now that he’s back in her good graces. It was when she was fifteen that she began to worship the ground Tab walked upon. He was her favorite star and she kept a scrapbook to prove it.

Natalie then decided that having the same agent should be of some advantage, and she hounded him to arrange a date with her idol. After a while, Tab consented with an unenthusiastic, “Okay, okay, I’ll take the little girl to the benefit next week.”

When he called for her, he offered his arm. Natalie almost refused it, since it happened that Lori Nelson was on his other arm. At the end of the evening, Miss Wood came storming through the front door. Her first words were, “Mother, take that scrapbook away! I’ll never collect Tab Hunter’s pictures again!”

Natalie frequently has crushes. “But I’m always conscious of the fact that I don’t think it will get serious,” she says. “I’m not thinking of marriage just now.”

At the moment, she is not domestically inclined. When she was eight, she baked pies, made beds, helped clean house and thrilled to the sight of soapsuds in the dishpan. Recently, she attempted to broil a steak and nearly smoked the family out of the house. “Domestically, I must be going backwards instead of forwards,” she observes with no trace of regret.

“When I do marry,” she continues, “I don’t want it to be on the spur of the moment. But right now, if I even started thinking of marriage, it wouldn’t work. I don’t want to get serious for three or four years. I’m too interested in my career and having a good time dating a lot of boys.”

That she takes time out for serious thoughts is obvious to those who have encountered Natalie during such moments. After the making of “The Searchers,” Pat Wayne had a hearty respect for her acting, Scrabble and gin rummy ability. He also made another observation with which Hollywood and the public agree. “Natalie strikes me as being older for her years than most teenagers,” he says admiringly. “She acts older, thinks older. She’s—well, she’s so much more mature than other girls her age.”

Natalie’s opinions astound many who meet her for the first time. There was, for instance, the reporter who was rounding up star quotations. He wanted a teenage theory and approached Natalie with the query, “What custom would you do away with, if you had your choice?”

He waited, wondering if it would be parental supervision, curfew, homework?

“I’d abolish capital punishment,” replied Natalie.

As one friend put it when he heard of her retort, “Natalie isn’t one for picking up a paper and turning straight to the comic section.”

“Most kids read the newspapers and know what’s going on,” says Natalie. “Teenagers have a lot more intelligence than they’re given credit for. What they need is more understanding.”

“Rebel Without a Cause,” the picture which introduced her to the world as an ingenue, is a plea for that understanding. And careerwise, as well as otherwise, it was a turning point in her life. “I call it my first picture,” she says, “because the rest don’t really count.”

“Rebel,” with Natalie, Sal Mineo and the late James Dean, is a picture that touched not only the lives of those connected with the filming, but the lives of the millions who have seen it. Since its release, Natalie’s fan mail count has soared to ten thousand letters per month, and among those letters are messages from mothers as well as teenagers. “My youngster has been to see the picture seven times,” wrote one. “I’ve seen it eleven.”

Parents write to say that they send their children to see “Rebel,” children write to say that they send their parents. “I learned so much from the picture,” says Natalie. “We all learned—about juvenile delinquency, parent-child relations, parent-teacher relations. That was something in itself.”

The moment she heard that the picture was planned, Natalie went after the part. “She sensed the importance that it would have for her career,” says director Nicholas Ray. “So did a lot of other girls who were trying to get the role. I must have interviewed at least a hundred actresses. Yet there was something about Natalie . . . a quality of reality.

“I tested around fourteen or fifteen girls. But in spite of the fact that the transition from child actress to ingenue is a very difficult step and the odds are usually against anyone being able to make it, it seemed to me that Natalie was the one who could do the part—and also show the most promise for the picture and the studio.”

That Natalie was concentrating on the role soon became obvious. Several weeks before she was told that the part was hers, Ray received a telephone call from a young stranger. “Mr. Ray, we don’t want you to be worried, but we’ve had a little accident.”

“Who is we?” inquired the director.

“A friend of Natalie’s and I—and Natalie. Well, sir, we were coming down Laurel Canyon and skidded. . . .”

“Where are you now?”

“I don’t want to worry you, but we’re at the emergency hospital in Hollywood . . . and Natalie may have a concussion.”

“Have you called her doctor? Her parents?” asked Ray.

“No . . . we thought we’d better call you first.”

Giving instructions to telephone Natalie’s family, Ray then phoned his own doctor and headed for the hospital. He and the Gurdins and the physician arrived at the same time. Natalie was examined and it was found she didn’t have a concussion.

The group went into the room where she was being treated. Natalie beckoned to Ray. “Do you know what the intern called me?” she whispered. “He called me a juvenile delinquent.” She gave him a weak grin. “Now do I get the part?” she asked.

“This was no scatterbrain speaking,” says Ray. “Just a very determined girl. And an intelligent girl. She’s a student and a bright one.

“During production we had the problem of school—of being able to work with her only three-and-a-half or four hours a day,” Ray continues. “It was Natalie’s senior year and she graduated that June with a very high average. But, in the meantime, she was going straight from geometry and other studies into playing her role. That takes a lot of concentration, preparation and stamina.”

During school, Natalie and Sal Mineo pulled a joke on their teacher. And, for a while, they thought it was a fine one. The instructor had to leave the classroom and, while he was gone, he received a phone call.

Whoever was on the other end of the line claimed to be the head of the Board of Education. However, pupils Wood and Mineo were certain it was their teacher, with voice disguised, checking up on them. Consequently, they began telling some pretty ridiculous tales about him. Then they began to worry.

“What if it was the head of the Board of Education?” asked Sal.

“Then we’ve done something awful,” replied Natalie. They were both fond of the fellow.

They sweated it out for a week, then discovered that they had been right the first time. The teacher had placed the call to himself. Then Natalie went into her act. “This is terrible,” she moaned. “We called the real Board of Education and told them we didn’t mean all of those things we said about you.”

Now it was the teacher’s turn to worry.

On the whole, however, the set was a serious one. In “Rebel,” Natalie found a new approach to acting. She went into more detail than she had ever done before—relating the part to herself, making it real to herself. “We covered as much of her personal history as possible, anything we could use to associate with her role,” says Nicholas Ray. “The characters in ‘Rebel’ were made up, but we gave them backgrounds of familiar things.

“We discussed the character of her father—a man very different from Natalie’s own father. She had no relationship to the character at all, but she had known fathers like the one in ‘Rebel’—the kind who had to be a hero to his family and ridicule his daughter’s friends.

“If a line of dialogue sounded wrong to any of the kids, we always made a change,” Ray adds. “On the other hand, they had the kind of talent that could make what seemed like corny lines become a part of them, as if they’d always said them. They weren’t playing effect or result. They were playing from the inside out.

“Natalie did some growing up during the movie. But she hasn’t grown faster than the average child,” says Ray. “By living so much of her adult life in an adult world, perhaps she does have a little more poise and self-assurance. But it comes from accomplishment. There’s a stubbornness which results from accomplishment, and it says, ‘I have the right to ask.’ Everybody does, but so many are intimidated.

“What’s so refreshing about Natalie is that her poise can break in a second. It can happen at any time. I was at her home the other night to watch a TV film Sal Mineo made recently. Sal was there, cracking jokes. Some of them were pretty corny Natalie fell right into it and went into hysterics. She was having a ball.

“The playwright who was with me found it difficult to believe that she was a girl who could play mature parts.”

Yet Natalie had proved it to the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. For, only a few nights before, she had received an Oscar nomination in the supporting actress classification.

She hadn’t been nervous about the event—not at first. “Why should I have been?” she asks. “We went to watch the other people get the nominations. I never thought I had a chance.

“Jo Van Fleet is my favorite actress and I was clapping so hard when they read her name that I didn’t hear them call my own. I still remember trying to get to the stage, climbing over so many people’s feet. Then I wrote my name on the board and we had pictures taken. After that I was in such a trance, I didn’t know what was going on for several days.”

Natalie, now eighteen, is the youngest actress to be nominated for the supporting actress award since Bonita Granville got the nod for her performance in “These Three”

“What took you so long?” one of her friends teased. “Bonita was much younger.”

“Bonita’s nomination happened twenty years ago,” grinned another real pal. “So you see it’s taken a fairly long time for another kid to make the grade.”

But that’s what you get when you’re a movie star—and your name is Natalie Wood.

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956