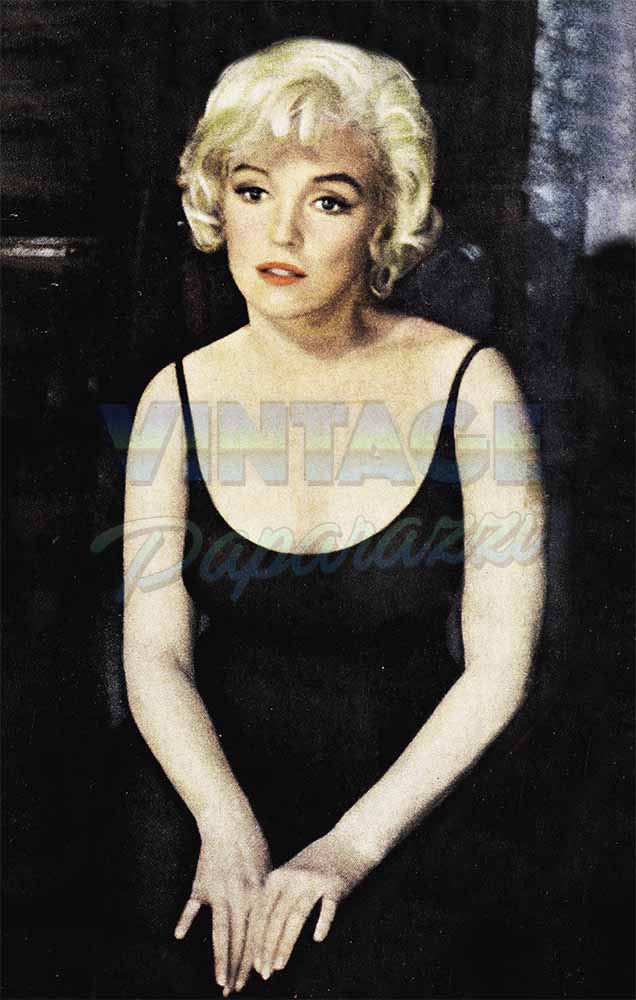

The Marilyn Monroe Mystery Grows

Nine months have passed since her death. And, still we feel an awful loneliness, an emptiness for her. For Marilyn Monroe.

Nine months have passed since her death—a summer waned quietly away, an autumn yawned, a winter blustered and a spring is being born around us, just about now. And yet she has been gone all this time. No longer a part of the seasons, of the world, of this thing called life. Though it is hard to believe. Very hard—when we read about her and talk about her and look down at a wistful photograph of her and when we watch her go through some of her glorious moments in not-so-old movies on TV and when-unavoidably, sadly as now—we simply think about her.

For nine months people have been asking: Why did she die? Why did she take her life?

But the answers are unimportant now.

Except for one—that she thought no one cared about her, she thought no one loved her or would, ever.

She was—this marvel, this outward- looking voluptuary. this so-called sex queen, this peer of Venus, this ever-to-be child who was christened by Hollywood at age nineteen with a sprinkling of champagne and a robe sewn heavy with spangles, this Marilyn Monroe. She was—in all reality and though few people realized it—a terrified and lonely young human being. Who—as one person has written— “stood alone at an empty mailbox for most of her life, waiting for a letter that might one day come and that might have written over its signature the small word: Love.”

In a way, the letter, the love letter, in fact the love letters did come—although Marilyn, perhaps afflicted with that blurred vision peculiar to some people who have been followed unmercifully by shadows, could not see them.

After all, there were people who adored her, and who told her so, day after day, time after time.

But—and this is the simple truth—they were in most cases busy people, with their own workaday cares and problems. Who, understandably, could spare only so much time for Marilyn. Who could profess only so much love for her.

And it was only after her death when they—like everyone else—realized just how much love this poor and unsure girl had really needed.

And then they wrote the words which, in life, she had never quite been able to hear. . . .

They wrote then—as they are still writing, nine months after her death—of her beauty, a beauty which Marilyn feared she was losing. And they wrote of it in the true terms of that beauty—as something timeless and ageless and unforgettable.

Dorothy Kilgallen, for instance: “You have left more of a legacy than most, sweet girl, if all you ever left was a handful of photographs of one of the loveliest women who walked the earth.”

Sidney Skolsky: “There were plenty of blondes before Marilyn. Since, there has been an army of blondes trying to be Marilyn. But the people knew the difference. The people knew.”

Nunnally Johnson, the producer: “She was a phenomenon of nature, like Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon. You couldn’t talk to it. It couldn’t talk to you. All you could do was stand back and be awed by it.”

A Photoplay reader (one of the thousands who has written to us about Marilyn since last August) : “At the beginning, I’ll admit. I thought she was kind of cheap- looking. It wasn’t Marilyn’s fault, I know now. It was the kind of roles they wanted her to play. Sirens and hussies and women of the world when she herself was so young. But Marilyn fought that kind of thing when she got big enough. And, slowly, she threw off the fakeness and she emerged as something real. I know a lot of people who didn’t like ‘The Misfits,’ her last picture. But I for one will never forget her in the final scene—when she stands there in that field and when she cries out to the men about to kill those horses. ‘Let them live. Please.’ A chill ran up and down my body which I can still feel when I think of it. She wasn’t dressed in a beautiful gown by Jean Louis for that scene. They didn’t have her hair fixed in any special and artificial way; in fact, they let the wind blow it around, just natural. They didn’t use any tricks. They just let her stand there and say the words and be herself as she felt the scene. And there she stood, just Marilyn Monroe as she was, crying out for mercy, crying out like a tiny Mother Earth for the salvation of all of humanity, and she was real in that scene. And a woman. And the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.”

They wrote now not only of her perfections, but of her “flaws,” if such they must be called:

Natasha Lytess, friend and coach: “There was more to Marilyn than met the eye. The trouble was that when people looked at her, they immediately figured her as a Hollywood blonde. It wasn’t their fault, though. Marilyn’s soul just didn’t fit that body.”

Mrs. Lee Strasberg, friend and coach: “Marilyn had the fragility of a female but the constitution of an ox. She was a beautiful hummingbird made of iron. Her only trouble was that she was a very pure person in a very impure world.”

They wrote now of her intelligence, of her intellectual impact—highbrows whom she feared had always laughed at her during those years when she had tried so hard to read all the “important” books and “understand” them and be able to “discuss” them.

Max Lerner, the distinguished columnist, for instance: “It is hard to think of the movie world or the American life without her as part of the landscape. When you said Marilyn you never had to add the last name. She was of our time and place and of our cultural bone.”

Diana Trilling, the distinguished literary critic: “Among the very few weapons available to the artist in the monstrous struggle, naivete can be the most useful. But it is not at all my impression that Marilyn was a naive person. I think she was innocent, which is very different. To be naive is to be simple or stupid on the basis of experience, and Marilyn was far from stupid. No one who was stupid could have been so quick to turn her wit against herself or to manage the ruefulness with which she habitually replied to awkward questioning.”

A senior editor on Time magazine: “Marilyn was never more than Hollywood’s plaything, when she might have been its lesson and guide. What things she had to say were never heard because her voice was a dog whistle in a town accustomed to brass bands. Her misery was less the price of living up to an image too big for her than living down the reflections of her own abysmal past, and her inability to share the lessons it taught her.”

They wrote now of her courage.

Someone on Vogue magazine: “She emerged from the hoyden’s shell into a profoundly beautiful, profoundly moving young woman. That she withstood the incredible, unknowable pressures of her public legend as long as she did is evidence of the stamina of the human spirit.”

A Photoplay reader: “I try to imagine sometimes what it must have been like for her—having to glossy herself up for public appearances, having to prove she was sick when she said she was, having to read some of the terrible things people wrote about her, having to smile for waiting photographers after a miscarriage—when her heart was really breaking— having to see one of her marriages wrecked after admitting practically publicly that she was in love with a certain married man and then having that man leave her. I try to imagine sometimes what it must have been like for her, having to live like that. And, trying, I find myself shuddering. How could she bear it?”

They wrote now of a genuine feeling of guilt for having ignored Marilyn’s courage.

Hedda Hopper: “In a way we’re all i guilty. We built her up to the skies, we loved her, but left her lonely and afraid when she needed us most.”

They wrote now of her tiny personal charms which, on screen, the paste of makeup sometimes succeeded in hiding and which were sometimes vulgarized by the hugeness of CinemaScope and Panavision and what-have-you and which one could only see on face-to-face contact.

Richard Meryman, an editor on Life: “If Marilyn Monroe was glad to see you, her ‘hello’ will sound in your mind all of your life—the breathless warmth of the emphasis on the ‘lo,’ her well-deep eyes turned up toward you and her face radiantly crinkled in a wonderfully girlish smile.”

A Photoplay reader: “I saw her once at a premiere here in Chicago. I stood no more than three feet from her when her car pulled up and she got out. I thought she’d be a snob about all this and bored—after all, this must have been the thousandth premiere she’d attended. But when she got out of that car, I couldn’t resist saying something to her. So I said the only thing I could think of in all that excitement, ‘Wow, you’re for real.’ I know it was a stupid thing to say. But she heard, and she smiled at me. And she said, ‘Gee, I sure hope so.’ And we both laughed for a moment, a very nice moment together.”

They wrote now of her very personal movie magic, and the career she felt was slipping by her—but which, in actuality, never would.

Natalie Wood: “When you looked at Marilyn on the screen, you didn’t want anything bad to happen to her. You really cared that she should be all right and happy.”

Someone on Time magazine: “Vague, troubled, shy . . . all the same she was a star; and it hardly matters that she never quite became an actress.”

They wrote now of her sweet and genuine innate capacity to be a good friend —to the young and the old, the famous, the friendless and those little heard of.

Mr. Isadore Miller of Brooklyn, her former father-in-law: “She was a kind, good girl. She helped a great many people, and their names will never be known. She was charitable because there was charity in her heart, not because she wanted thanks . . . At the President’s birthday ball last year, I remember, she said I was her date and when we went up to the President of the United States, instead of saying, I’m pleased to meet you, Mr. President,’ she said, ‘I want you to meet my father-in-law.’ I’m sure that she was thinking about the thrill I was getting instead of etiquette. That’s the kind of girl she was, my Marilyn.”

Peter Lawford: “She was always gay, she made our parties when she came. She was honest, marvelous. They say she was naive. Well, perhaps Marilyn was naive in one area. She gave so much of herself to others, was so eager to do things for people, that it made her vulnerable to pain. There wasn’t a mean bone in her body.”

Carl Sandburg, the poet: “She had vitality, a readiness for humor. She was a warm and plain girl. The first time we met it was as if she wanted to see me as much as I wanted to see her. We hit it off and talked long. The last time I saw her I didn’t rise and escort her to the elevator when it was time for her to leave. I’ve never been good at manners. But I am eighty-four years old. I hope she forgave me.”

They wrote now of having known her well years ago, when she first got started on her career in the movie business.

George Jessel: “I made her first important test for a movie. I took her to her first Hollywood party, given by Louis B. Mayer for Henry Ford II. I have a picture of us in front of me right now. She had nothing to wear. We had to dig up something for her from the Wardrobe Department. Yet, she was the most beautiful girl at the party.”

They wrote now of having known her only fleetingly, but memorably.

A Photoplay reader: “I lived not far from her East 57th Street apartment house for a time, when I was working as a secretary in New York. I would see her sometimes at night—coat collar pulled high, kerchief on her head—as she walked a small dog in a small, nearby park. I knew she was a great film star and- often bothered by pests and so I never approached her, not even to say how much I admired her. But one night I happened to be at the park, just taking some air. I happened to be wearing a new coat I’d just bought, a black and white tweed car coat, not expensive, but nice enough. And do you know—but she looked at me that night. And she smiled. And she walked over to me and said, ‘I hope you don’t mind, but I must say how pretty that coat is, and how becoming on you.’ She, Marilyn Monroe came up to me. And she felt very free to say that she admired something about me.”

Joseph Spadare, a public relations man on Long Island: “It was in Amagansett, a few summers ago. I was driving and she was walking down the road with a child. So I did a double take, I backed the car around and I said, ‘Are you Marilyn Monroe?’ She was wearing dark glasses. ‘How did you recognize me?’ she said. I told her I just did and she said, ‘Do you want me to take my glasses off?’ and she did, and then she said, ‘Why don’t you pull the car over, we’ll talk.’ And I did. We talked for a long time. It was very personal, very sweet. She was a nice girl . . . with dungarees . . . out in the country . . . with a child.”

They wrote now of her intense love for children.

A friend: “It was the great tragedy of her life that she could never have a baby. She never spoke about this to anyone. But the tears, they always touched her eyes whenever she looked at someone else’s infant.”

Alan Levy, journalist: “She said to me once, about her three former stepchildren (Robert and Jane Ellen Miller and Joe DiMaggio Jr.), ‘I take a lot of pride in them. Because they’re from broken homes . . . I can’t explain it, but I think I understand about them. I think I love them more than I love anyone. I’ve always said to my stepchildren that I didn’t want to be their mother—or stepmother—as such. I wanted to be their friend. Only time could prove that to them and they had to give me time. But I love them and I adore them. Their lives that are forming are very precious to me. And I know that I had a part in forming them.”

They wrote now of the one man who had truly loved her—a man who somehow hadn’t been able to show it, not all the way, not one hundred per cent, while she lived.

A reporter for Newsweek magazine: “Three times each week, a florist delivers six long-stemmed roses to Marilyn Monroe’s crypt at Westwood Memorial Park. The sender: Ex-baseball star Joe DiMaggio, second of Marilyn’s three husbands. A cemetery official told of the flowers, adding: ‘Mr. DiMaggio said they were to be provided forever.’ ”

They wrote now of their own feelings of loss.

Again, Diana Trilling: “I think my response to her death was the common one—it came to me with the impact of a personal deprivation but I also felt it as I might a catastrophe in history or in nature—there was less in life because she had ceased to exist. In her loss life itself had been injured.”

Again, Isadore Miller: “I lost a daughter when she went. She was like my own.”

Again a Photoplay reader: “I think about that Saturday night when she sat there alone, contemplating death and thinking only sad thoughts—I feel, as I’m sure countless others do, that if only / could have been there to talk to her, to remind her of the things she had to be happy about, to remind her that we all of us have our problems. To at least just talk to her, so she wouldn’t have had to feel so alone and maybe to say to her. ‘Don’t do it. Please, don’t do it. You’ve got so much to live for, and we’ll all miss you so much, and there must be another way. There must be another way . . .’ ”

And so they wrote.

And wrote.

These past nine months.

Of Marilyn.

To Marilyn.

Letters . . . letters . . . all the letters she ever waited for and all signed: “Love.”

They were the letters Marilyn Monroe had waited for in life and had never received.

—ED DE BLASIO

See 20th’s upcoming new film, “Marilyn.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1963

zoritoler imol

23 Nisan 2023I like what you guys are up also. Such smart work and reporting! Carry on the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my site 🙂