The Loneliest Bride In Hollywood—Christine Carrère

This is the first story we’re running about Christine Carrère. We think it will be the first of many. Christine is very French and very pretty and very much one of the most lovable young things to hit Hollywood in a long, long time. As we go to press, she has just completed her starring role in A Certain Smile, from the novel by another young French girl, Françoise Sagan of Bonjour Tristesse fame. Christine is now rehearsing for her second American picture, Mardi Gras—in which she plays opposite Pat Boone. But enough of the present for now! Let’s go back a little instead to Christine and a certain night in her life not too long ago. . . .

It should have been one of the greatest nights in Christine’s life—stepping off the plane from Paris and smack into Hollywood, the flashbulbs going off, the flowers, the fuss, the quick trip to the hotel to freshen up and then the quick trip to the party where all her favorite stars, Gary Cooper and Lauren Bacall and Van Johnson and dozens of others, had gathered to greet and welcome her and wish her well in her first American picture.

It should have been a great night for Christine. And it was, in a way. At least, at the start.

Except that the moment finally came—a few hours after the party, after the laughter and toasts, the being surrounded by all that glamor and all that glitter—when Christine was alone, terribly, suddenly, frighteningly alone.

It came a little while after she’d fallen asleep, in the middle of the dream.

It had started out as a nice; sweet dream. . . . She was young, just a little girl, and she was in Paris. She and her mother were in the living room of their little apartment and her mother was opening a big be-ribboned box and was about to show her daughter a party dress she’d bought her. Christine was excited. She laughed and she tugged at her mother’s arm and she urged, “Vite, Maman, hurry!” But then the noise had come. It came from outside the window and over the tiny garden, very soft at first, like a baby’s wail. They had both looked toward the window at the same moment. Then her mother put down the box and turned to Christine. She had been smiling before, but there was terror in her eyes now. “Come,” her mother said, rising and taking her hand, “it is the Germans in the airplanes and we must go to the shelter!”

Christine half awoke now on the sound of the word “shelter.”

But she did not awake completely, and still the dream was there. And as it continued she could hear the noise from out the window growing louder and louder, not like a baby crying anymore but like the stark announcement of death’s approach. And she could see herself being dragged out of the apartment and down the street, she and her mother running crazily toward the sign that read abri—shelter, the other people pouring out of their houses and running too, the blood-red glare of the sky on the other side of Paris where the Germans had already dropped some of their bombs.

Finally, the wailing noise grew so loud that it woke Christine, really woke her.

“Philippe!” she shrieked, as her eyes snapped open.

The room was pitch-black and she could see nothing. She reached out, desperate, to the other side of the bed.

“Philippe!” she said more softly. For an instant, everything was confusion. Half her mind knew that this had all been a dream—that she was a big girl now; that the war with the Germans was long over; that she was in Hollywood, California, far from France; that Philippe was not there in bed beside her.

But the noise, the wailing noise. That was not part of any dream. That was real. The noise, the terrible noise. Where was that coming from? And why did that not stop?

She jumped out of the bed and groped through the darkness to a window. It was open slightly. She pushed it open all the way and listened.

Slowly, very slowly, she realized that the noise was coming from a fire engine that had since passed the hotel and was now miles away, its siren still piercing the still night air.

Her first instinct was to laugh.

Except that she couldn’t laugh, and so instead she began to cry.

“Philippe,” she said again, whispering the name this time through her sobs as she stood there, staring out the window. “Oh, Philippe—” she said, as if she were calling for someone to come be with her and comfort-her and, with his arm around her waist and his lips against her hair, dissolve the ache that filled her young lonely body.

But no one came.

“It is silly to cry like this, is it not, Philippe?” she said anyway, just pretending. “I remember my mother used to say to me when I was very little that if you cried about anything at night, alone in your room, you should immediately think of something happy that has happened to you. ‘And puff!’ she told me, ‘the tears will vanish!”

Christine nodded at the memory of that advice.

And then, still standing there, she searched back in her mind, way back, for some of those happier moments.

They came to her in flashes.

Boys, I like

Like the day, when she was six or seven, at her uncle’s farm in. Burgundy. . . . Her uncle had a beet-sugar farm. He also had a young son and two daughters. When Christine arrived on the farm for a short vacation—a vacation from school and from the war that raged in the north of France—she was introduced to her cousins and then told to run off and play with the girls.

“There are two things I do not like,” Christine told her amazed uncle on the spot. “One is arithmetic. And the other is girls.”

And so Christine galloped off with her boy cousin, out to the fields to meet some other friends who were playing there.

For the next three hours they all played a farm version of soccer, using the big, heavy sugar beets as the ball.

When the game was just about over, Christine’s uncle came out from the barn where he’d been working to see how his niece was enjoying herself.

“But my child—” he said, stunned, when he saw her. She’d just taken what must have been her fiftieth fall and was covered with blood and bruises. “You must not play like this!”

“Uncle,” Christine said, taking his hand and smiling a strange smile, “always in Paris I have gone to school with girls. As I said, I did not like them. And always I wondered about boys, whom I did not know. ‘Would I at least like them?’ I asked myself. Well, uncle—I do. So please let me play on with them.”

The man had no choice but to laugh and say all right.

He had stayed around, Christine remembered, long enough to see her score three more goals and get herself two more cuts. . . .

Another happy memory

And—Christine remembered, too, now—there was another happy time on another day, years later, and with another boy. Actually, the boy was approaching young manhood, being about nineteen years old to Christine’s fifteen. Actually, too, Christine had no use for this particular boy because he was known in the neighborhood as the young handsome Don Juan and Christine, still a tomboy at heart, didn’t like anything or anyone romantic.

But she had just had an appendectomy and she was in the hospital and this boy had come to visit her and she knew she must try her best to be pleasant.

So, whatever he would say, she would answer, “Oh, yes?” And, “Oh, is that so?” And, “Really—well, how interesting.”

She was, in truth, not really interested in anything about him, so suave, so slick, so much the type all the other girls—silly things—were always mooning over.

But then, just before he left, he leaned over her bed and kissed Christine lightly on the forehead and he said, “You know, you are a very pretty girl.”

For the first time in her life, Christine blushed.

“No,” she said, trying to cover the blush with her words—true words, she thought. “I am quite ugly. Look, my face is chubby and there is nothing distinctive about it and—”

The boy shook his head. “You are so pretty,” he said, “that if you were older, I would come call on you—often.”

With that, he kissed her again and left.

And with that, Christine reached for a mirror and began to study her face.

When her mother came to visit her a little while later, the woman was amazed.

“What have you done to your hair?” she asked, coming toward the bed.

“I have pinned it back a little,” Christine said, “like the true Parisiennes are wearing theirs.”

“And what is that on your lips?” the woman asked, coming closer and closer.

“I know, Maman,” Christine said, “I must not wear lipstick until I am seventeen years. But the nurse had some in her purse and I asked her if I could try it, just to see how I will look when the time comes.”

Her mother shrugged.

“Maman,” Christine said seriously, in the tone she always used when she was about to confess something. “Maman, I am beginning to grow old.”

“Old?” her mother asked.

“Well, older,” Christine said. “And I think—I think I now like boys.”

“But you always liked boys,” her mother said, very matter-of-factly. “The soccer, the water polo—”

“Yes, Maman,” Christine said, nodding, interrupting her, “but now—I like them in a different way.”

The woman looked at her, stunned for a moment.

And then, suddenly, she began to laugh.

The garden party

How we both laughed then, Christine remembered now, this first night in Hollywood, standing by the open window, thinking back. “But how Maman didn’t laugh that afternoon the next year when I came home and told her about the charity garden party and the movie stars and the producers and what they had all said to me. . . .”

The party was held in a movie producer’s garden in the heart of residential Paris. Every top movie personality in France was invited. Not invited was a young wide-eyed girl, by this time one of the top movie fans in France. Her name was Christine. And to get into the party, she just kind of walked in.

Her reason for doing this was two-fold: she wanted to see her favorites in person and she wanted autographs.

She’d been sneaking around the place for almost an hour and had already seen most everybody there and gotten a padful of autographs when two men and a woman, sitting sipping champagne at the far end of the garden, signaled her over.

Christine recognized one of the men as Noel-Noel, the great comedian. She’d already gotten his autograph, a long time back. She was confused. “You want me?” she called out.

The three nodded.

Praying suddenly that one of the other two people was not the host or hostess, ready to boot her out of the garden, Christine walked toward them.

“You see what I mean?” Noel-Noel asked, taking Christine’s hand in his. “You see?”

“Yes,” said the other man, who turned out to be producer Jean-Paul Paulin.

“She is lovely,” agreed the woman—Jacqueline Audry, another producer.

“What are your measurements, Mademoiselle?” Noel-Noel asked.

“I don’t know,” Christine said nervously.

“Whatever they are,” said Paulin, watching her, “they are good.”

“And what is your name?” Mme. Audry asked.

“Christine de Borde,” the girl said, methodically, as if she were answering a job questionnaire. “My father is the Count Ivan de Borde. He is a gentleman farmer and long separated from my mother. I live with my mother.”

“And you would like to be a actress?” Mme. Audry asked.

“No . . . At least—I never thought about it.”

“You are a student?” she was asked.

“Yes,” Christine said. “I go to the secretarial school.”

“You like it?”

“I do not like it at all,” Christine said. “But since the war we have been poor. My mother must work and I realize I must help her, so I am studying to be a secretary. It is an obligation and I realize I must be happy at it. It is something I must do.”

At the very moment she said that, a quality in Christine—a warm, sad, bittersweet quality—came shining through.

“You see?” Noel-Noel said triumphantly, turning again to the others.

And again the others nodded. . . .

Mama is skeptical

A few hours later Christine was excitedly telling her mother, “The woman producer said to me that I should come tomorrow to the studio for a film test and that if it was good she would put me into a movie.”

“You are sure this was a woman producer?” her mother asked, skeptically.

Christine described Mme. Audry and what she had been wearing, from her beautiful hat right down to her beautiful shoes.

“Well,” her mother said—and then she thought for a moment. And then, with great finality, she said, “No, you may not be an actress. The cinema is not a good business and too many young girls like you are led into it with promises and then let out with nothing but a broken heart!”

And that should have been the end of that. Except that for three days running, Christine—suddenly intrigued with the idea of visiting a real movie studio and making a real test—bothered her mother so much that she finally gave in.

It was on a Friday that Christine phoned the producer saying that she could come for the test. The following Monday she made the test, and by Wednesday she was called back to the producer’s office.

“This is fantastic, I know, Christine,” the woman told her, “but I think you are an actress.”

She handed the girl a script.

It was for a picture called Olivia.

In it was a part for Christine, a small part, but the kind that can do wonders for a young actress.

As it turned out, this particular young actress ended up doing wonders for the part.

And so began a beautiful career for the newly-named Christine Carrère.

And so also began the strange chain of events that would eventually lead to her meeting the young man named Philippe.

She didn’t like him at all at first.

As she explained it in a letter to a friend, one of Christine’s very few close friends:

This morning I started work on a picture called SPRINGTIME IN PARIS. My co-star is Philippe Nicaud. You remember how I used to idolize him on the screen? Well, he is terrible to meet. He is good-looking, yes; but not really so great-looking. And he is so self-assured, so certain of himself—unlike myself, who is more quiet, and a little insecure. And yes, he is a good actor—but that, too, he knows. Honestly, my only reaction to him is: “Here is a man who is very happy with himself!” Well, you know how I feel about that type—

In her next letter, written about two weeks later, Christine wrote all about the progress of the picture and the fun she was having making it. There was only one reference to Philippe Nicaud this time. It read:

Oh yes, about him—we’ll be working together soon. And I can’t say I look forward to it.

Not long after, in her third letter, Christine wrote:

I have always liked and respected you, my good friend, but I think you are very silly to say that I have some sort of ‘feeling’—as you put it—about Monsieur Philippe Nicaud. I feel absolutely nothing.

And then, almost immediately after that, followed the fourth letter:

It was a difficult scene I was working on all day today with Philippe, our second scene together. Both of us were having a little trouble with it. And then, do you know what happened? He asked me if I would have lunch with him, so we could talk about the scene, he said. At lunch we talked about the scene and then we began to talk about ourselves. And do you know what? He was so nice to me and so helpful. After a while I realized that though he is a strong person he is not that strong—and that some of his attitudes which I didn’t like are really used by him to cover up the feelings inside him about not being so sure of himself. Anyway, he asked me to have dinner with him tonight. And this will surprise you—or will it?—but I said yes!

That evening with Philippe turned out to be the most wonderful Christine had ever spent.

And that evening led to another, and another.

Finally came the evening a few months later when—sitting together in a small Left Bank restaurant, their dinner over, sipping the remains of a small bottle of sparkling red wine—Philippe asked Christine to marry him.

“But there are things about me you should know,” Christine said, suddenly flustered.

“Oh?” said Philippe.

“I don’t like the color green,” Christine said.

“Neither do I,” said Philippe.

“And I hate to travel on airplanes.”

“I have always preferred the train myself,” said Philippe.

“And in my spare time sometimes I like to write novelettes. Only—until I write one I like very much—I will never let you read it,” Christine said.

“I promise not to ask,” said Philippe.

“And about my cooking,” she continued, “I know all French girls are supposed to be good cooks: I am, too. But I don’t like it. I give too much of myself. Then if it’s no good I want to cry—and, believe me, sometimes it is no good.”

“I have a very simple appetite,” said Philippe.

He looked into her eyes and took her hand in his.

“Will you marry me, Christine?” he asked again.

“Yes,” Christine said, radiating happiness. “Yes. . . .”

Hollywood beckons

But word from Hollywood interrupted their wedding plans. The word was simple: Twentieth Century-Fox wanted to test Christine in their London studios for the lead in Françoise Sagan’s A Certain Smile.

It was marvelous news in a way. It would mean Hollywood. It would mean co-starring opposite someone like Rossano Brazzi. It would mean everything a young actress could ever hope for.

Yet it was sad news, too—news that could mean not only putting off the wedding, but being separated from Philippe for month upon month upon month.

Christine didn’t know what to do.

Philippe persuaded her to make the test.

Somewhat reluctantly, Christine flew to London. In the back of her mind was the strong belief that she wouldn’t make it. After all, she knew no English—and hadn’t that held her back once before, the time she’d been considered to play opposite Kirk Douglas in Act of Love? And if you only half heartedly wanted something, weren’t the chances pretty slim that you would get it?

But when Christine arrived in London, she really worked on the part. For days, she worked on two scenes. She learned her lines phonetically because although she couldn’t read the English spelling, she could learn the sounds. Then she took her test and the prints were rushed to Hollywood.

And, a few days later, a contract was rushed from Hollywood back to Paris.

“Sign it,” said Philippe, who had just been notified that he too had landed a plum part—the romantic lead in a stage play called The Pretender. “Sign it, and we will be married anyway. And what will happen after that, will happen. . . .”

The wedding, a few months later—after Christine had gone to Hollywood to perfect her English and prepare for the picture—was small and lovely. So was the bride. She wore a dress, with a bolero top and short tulip skirt designed by Dior, a veiled hat with a pony-tail of white satin roses, and carried a tiny bouquet of white roses and lilies-of-the-valley.

The church ceremony was held at Notre Dame Auteuil, with one near-mishap: when it came time for Philippe to reach into his pocket for Christine’s ring—in France it is the bridegroom who carries the ring, not the best man—it wasn’t there. Philippe was sure he’d put it in his pocket and he searched and searched. Finally, hopefully, he tried the other pocket and everybody present—especially Philippe—breathed a long sigh of relief when he came up with the tiny gold band.

Then Christine and Philippe and their forty guests drove to a small inn outside Paris for a champagne reception.

It was a beautiful party. And everything went beautifully, too, until it came time for one of the guests to make a toast. Lifting his glass, he spoke about this fine young couple, so much in love, embarking on their great voyage through life together. Then he reminded one and all that they should be proud that the play Philippe had just opened in was the hit of Paris, and that they should be proud that Christine would be leaving in just four days for the United States of America to play the lead in a great motion picture.

“It is a shame,” he started to say, “that they will be separated—”

Never let go

Christine never heard the rest. She was too busy now fighting back the tears. She managed to smile when the speech was over, as everyone applauded and drank to their health. But then she reached under the table and clutched her husband’s hand hard and she swore to herself that she wouldn’t let go of it until that night, so few nights away, when she would have to board the plane and leave him.

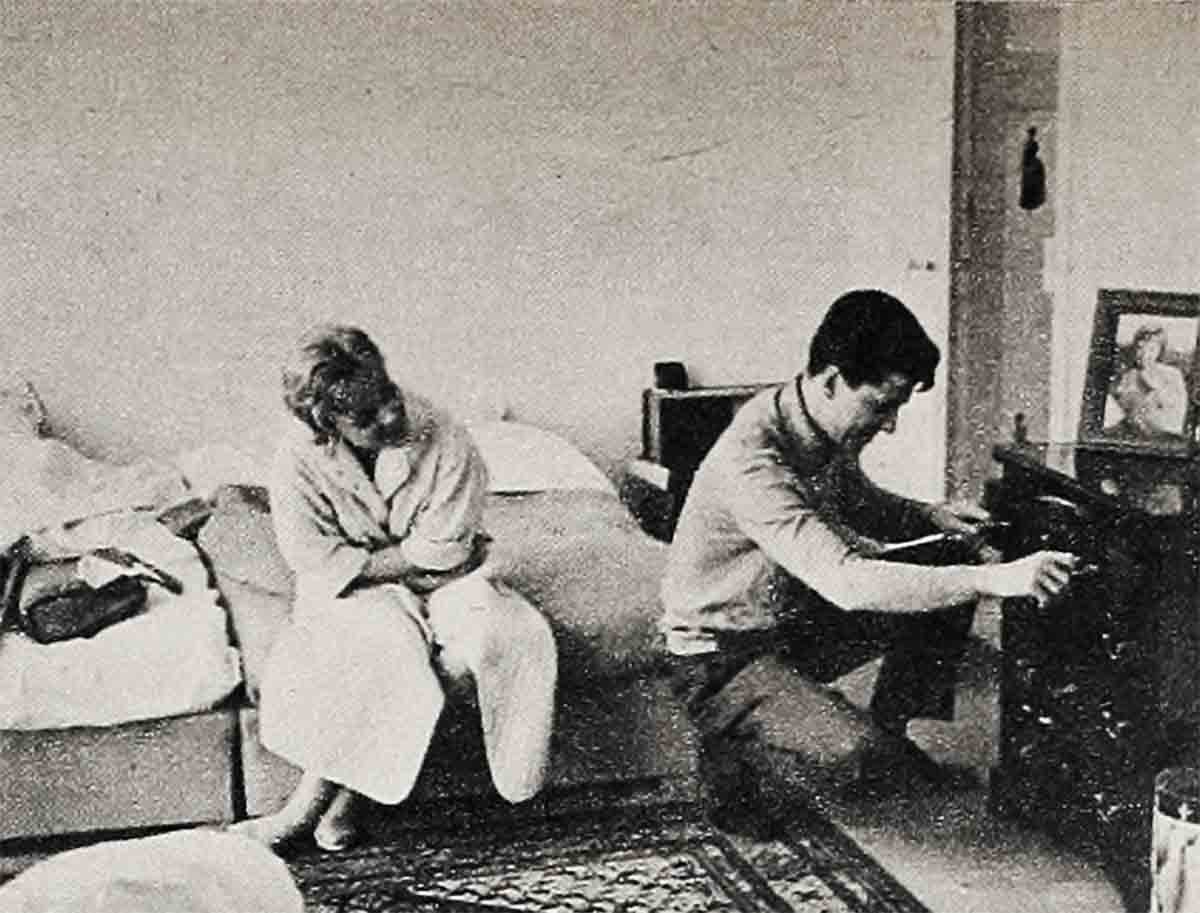

Their honeymoon was as wonderful as it was short. They spent it in their new five-room apartment, right there in Paris. They had no furniture yet—nothing but a couple of beds, a couple of chairs, a few dishes and kitchen utensils. But who cared? They had each other. And they had their big terrace overlooking the city below. And on the two evenings when the weather was nice Christine prepared dinner—simple, as she had warned Philippe, just steak, potatoes, pastry and coffee—and they ate on the terrace. And then, as night fell, they continued to sit there, just the two of them, watching the lights of the city go on, then looking up at the stars as they too went on. And they whispered to one another the things that people in love will whisper, trying to fill into those few days and nights what they knew would soon be only a memory. . . . The morning after her arrival in Hollywood—and exactly five mornings after her wedding—Christine got down to the business at hand—namely, to begin to work on her role for A Certain Smile and to try to wipe out the loneliness she was already feeling for Philippe.

For those next few months Christine was the loneliest bride in Hollywood.

Except that it would have been hard to tell if you didn’t know her very well.

“At night, Christine was always alone,” someone who does know her has said. “After a week she moved from the hotel to a small apartment. And after she got home for the day and made her dinner, she would either sit and study her script or her English, or go out for a walk, or turn on the little television set in her bedroom, and lie down and watch until she fell asleep. . . . But then day would come again and Christine would come to the studio. And so anxious was she to learn and be friendly, and so delightful a girl is she, anyway, that you would never know what she really felt about being separated from her Philippe. Of course, there were times when she’d be smiling a little more glowingly than other times. And if you pressed a little, she would tell you, ‘Oh, I spoke to my husband on the telephone last night!’ or ‘Tonight, Philippe will call me and we will be able to talk for a while!’ But other than those times, as I said, it was always a little hard to tell how she felt.

That smile

“And then,” the friend went on, “came the day, midway through A Certain Smile, when the studio decided to shoot part of the picture on location—in France. I was with Christine when she was told this. And to try to describe her expression would be like my telling you about my first trip to the moon. Let me just say that it was a combination of everything wonderful and happy and thankful in life, all put together in one pretty little face.

“The trip back to Europe must have been a dream come true. I don’t know exactly how much time Christine and Philippe had together in their new apartment. It was no more than a couple of weeks, tops.

“But in those couple of weeks they lived, the way some people never live, no matter how much time they spend together.

“And when Christine came back to Hollywood, finally, to finish the picture and begin work on another, she was in all truth a different person.

“Yes, she still spent her nights alone.

“And she was, no doubt, still lonely for her husband.

“But I think she learned something from that happy, though short trip back home.

“She and I got to talking about it. Philippe was still in Paris with his play; Christine was here for another few months with her new picture, Mardi Gras—a big bang-up musical with Pat Boone, Tommy Sands, Gary Crosby and June Blair.

“At one point she smiled and said, ‘You learn that the miles mean nothing when there is love at both ends of those miles.’

“Then, quickly, she changed the subject.

“But that smile she’d been smiling, that certain smile of Christine Carrère’s—that remained.

“And it was good to see that, at last, everything was très okay!”

THE END

Christine will soon be in 20th Century-Fox’s A CERTAIN SMILE and MARDI GRAS.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1958