The Boy Who Didn’t Belong—Bobby Darin

To a woman almost twice his age, he was the lover she wouldn’t let go. To teachers, he was the bright boy who often wouldn’t take the trouble to study. To himself, he was the guy who so hated the frustrations of each day that sometimes he wouldn’t bother to get out of bed.

Throughout his childhood and adolescent years, Bobby Darin was a one-man minority, the kid who didn’t belong. He says, “It was like being a displaced person.”

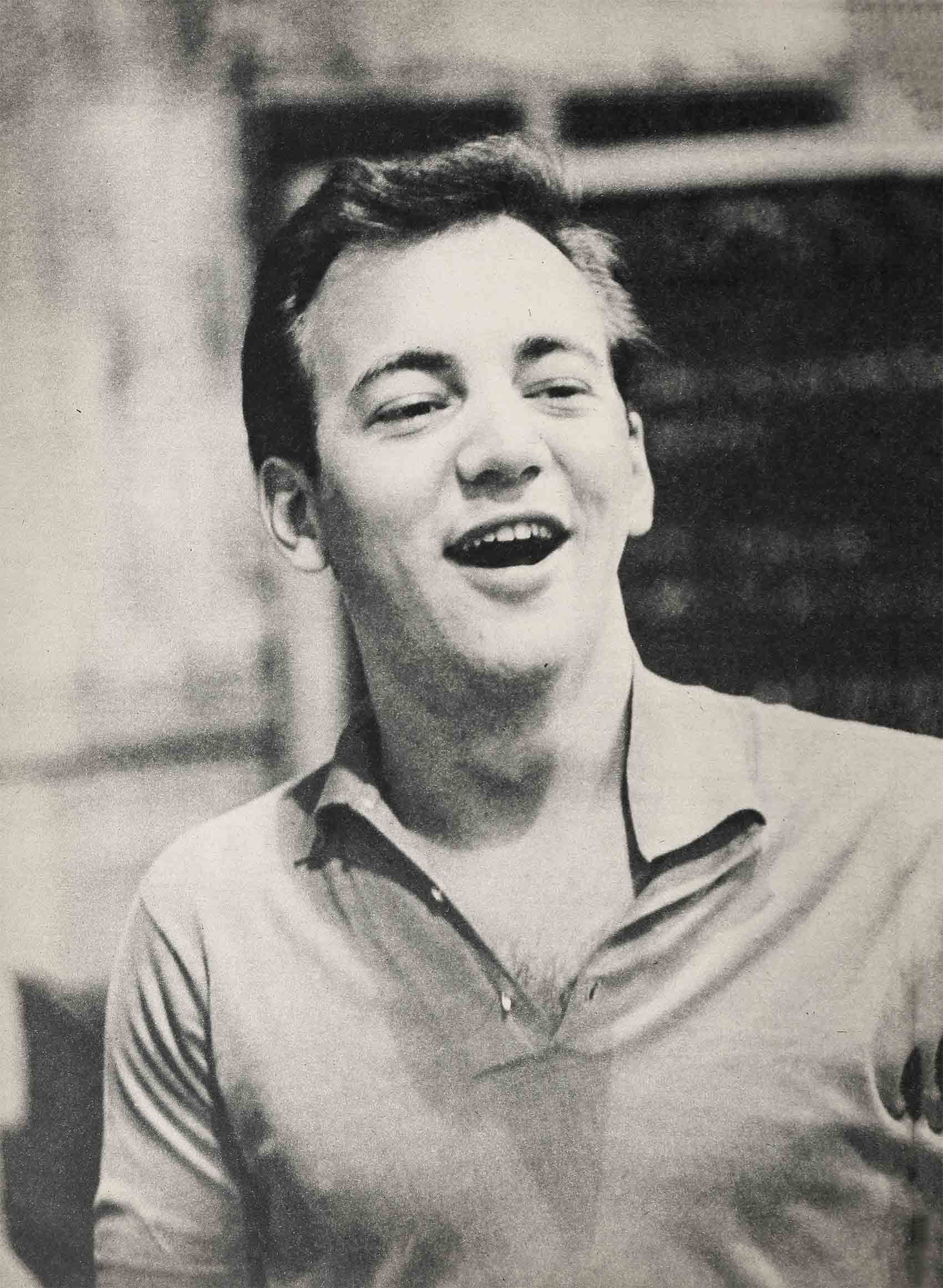

Today, Bobby Darin is still in the minority, but it is that glorious minority of top talent. Rebelling against hated situations gave him the drive to rise to the top. The record of what he has done is as reassuring as a handclasp to any young person whose ambitions set him apart in a lonely world of his own, for Bobby Darin is one who has found his place by turning his own dreams into reality.

During the past year, he has emerged from the large group of rock ’n’ roll singers to become an entertainer enjoyed by persons of all ages. His recording of “Mack The Knife” held Number One spot on the charts for weeks; he has an impressive contract with Paramount Pictures; he owns a recording company; he has harvested a crop of “top singer” titles; he has been the subject of Ralph Edwards’ “This Is Your Life” and is sought after to appear on as many major television shows as he will accept.

Yet despite this display of talent, there are those who, viewing his recent years, regard Bobby as a reformed beatnik. This makes Bobby boil. Recently, in a theater dressing room between shows, he stated his views most emphatically.

“I hate the word beatnik,” said Bobby. “Just because I was once down to my last pair of jeans doesn’t make me a beatnik. Before you call me a beatnik, you must define what a beatnik is. If, by a beatnik, you mean a guy who doesn’t care about anything, count me out. Even in my unhappiest days, I didn’t qualify. From the time I could walk, I knew what I wanted to do. I wasn’t more than two years old when I was marching around the kitchen, tooting a harmonica, being MacNamarra’s Band. Even then I knew I intended to become an entertainer.”

Bobby Darin, the dapper, poised performer, becomes the sharply analytical, intellectually angry young man when he speaks of childhood days. He was ready to fight the world for a chance to realize his ambition and, from the beginning, there was more to fight than one small boy, a loyal sister and a sick mother could handle.

Walden Robert Cassotto was born in New York City on May 14, 1937. His father, an Italian carpenter, died five months before he was born. “My mother was not a young woman,” says Bobby. “From that time on, she was ill. She couldn’t work. We had to go on home relief and she just hated it. She had always been able to accomplish so many things.”

With the pride of deep love, Bobby recounted them. Paula Walden had attended a small college near Chicago. “We’ve got a funny old picture of her on a bloomer-girl baseball team.” She had been in vaudeville. “Whenever I saw some one dance on television I was after her, demanding, ‘Mom, what step is that? Show me how to do it.’ ” After she married, she had taught school, held civil service jobs, done social work. “With such a background, you can see why we didn’t fit into some of the slums where we had to live after she was no longer able to work. Our neighbors had their troubles, too, many of them due to the lack of education. They couldn’t understand why an educated person should be on relief. Some resented us. They thought we were being snooty when we were just being ourselves.”

The gap widened when, at the age of four, Bobby contracted rheumatic fever. He was eight before he was able to start school. During these years, his mother and his devoted sister, Nina, read to him, talked to him, sang with him. Their teaching paid dividends. He completed six years of grammar school in four and finished at the head of his class. In junior and senior high school, however, his grades were only fair. “I never did come out even with the other kids in my class,” says Bobby. “First I was older, then younger, then older again. I loved to read and my vocabulary grew. The kids called me the walking dictionary and that didn’t make me many friends, either. I played ball when I could, but because of the rheumatic fever, that wasn’t very often. Again, I was a minority of one.”

About that time, a fourth important member joined the family team. Bobby’s sister, Nina, had grown to be a beauty, but her boy friends soon learned that the family was inseparable. Nina says, “I let them know that whoever married me got Mother and Bobby, too.” Charles Maffia, a refrigerator repairman, was the young swain who met the challenge and married Nina. Bobby acknowledges his influence by saying, “I’ll never be able to.repay the help he gave me.”

But Bobby’s dreams still set him apart. He entered the Bronx High School Of Science. “That was a sharp school where a great many academically gifted kids were out on a cold drive for straight A’s. I bucked for it just long enough to find out that I could hold my own, then I lost interest. I got no kick out of beating them any more. I didn’t care about A’s-in science; I wanted to learn music.”

Again, there were handicaps. “I was 18 before we latched onto a piano. I used the one in the school lunch room to learn to play. The only musical instruments we had—if you can call them that—were a harmonica and a beat up ukulele.” He borrowed a set of drums and organized a band. “I kept looking for some place in the world that belonged to me.”

He thought he had found it when he enrolled at Hunter College to major in drama and speech. He didn’t belong there, either. “The other kids in the dramatic society would go around quoting lines all day. I couldn’t remember a particular line for ten minutes. Instead, I was trying to dig deeper and understand what the author was trying to say about a character.”

He quit in the middle of the term. “I realized that something was bothering me and that it wasn’t going to come out as a result of books. The way I saw it, I was copping out from taking full responsibility for myself, using the excuse that I was getting an education. Going to college was only going to defer taking that responsibility for four years.”

He sampled the rigors of the road by touring with a children’s theater company, then returned to New York to try to get on the stage. He was keenly conscious that he was contributing little to the support of the family. Nina remembers, “Bobby shared whatever he had and he always tried to do something special for mother. Imagination was more abundant than money. He once celebrated a $30 a week job by bringing Mother one goldfish in a big brandy snifter.”

Bobby earned his keep by a series of unskilled jobs, such as cleaning drill machines in a downtown factory and cleaning guns for the Navy. He says, “I’d get a few dollars ahead, then quit to make the Broadway rounds. I wanted to be an actor, but nobody wanted me.”

It was then that he drifted into the love affair with the woman who was 31 to his 18. Bobby is still openly bitter about it. “She was a dancer. She had great plans for helping me with my career, but that woman was more mixed-up than I was. After six-months, I did break away, but I went into a deep spell of depression. For a year and a half, everything stank. I hate to think of all the days I wasted. I couldn’t face another closed door, and I couldn’t face myself. I was so mad at everything that some days I wouldn’t even bother to get out of bed.”

In that murky period, he didn’t realize that he had already started to put his rebellion to work for him. He is brutally honest about why he began to write songs. “It was the only way I had to get back at the woman for all the lies she had told and for what she had done to me.”

Those songs, plus a chance meeting in a candy store changed the course of Bobby’s life. An objective account of it comes from Don Kirshner, now a prospering young music publisher and singers’ agent. Says Don, “During summer vacation from Upsala College, I had happened to write a song which was accepted. The night that I met Bobby, I had my first publisher’s contract in my pocket. Actually, the contract didn’t mean a thing, but I didn’t know it then and I felt big. The mutual friend who introduced us said that Bobby wrote songs, too, and we went over to the friend’s house to listen to them.” The expansive hopefulness of that evening brings a smile now. Don says, “I thought Bobby’s songs were the greatest and I got carried away. I said I was going to make him into the top star of the country. The truth was that I had no more idea of how to sell a song than he did.”

Their first collaboration led only to deeper discouragement. “Bobby convinced himself that I was the one who was going to make it and at best, he’d only go along for the ride. He would vanish for days and the bunch of us who believed in him would have to hunt him up and start him writing again.”

Their first break was a contract to write singing commercials for a New Jersey radio station. “We got $500, which was more money than either of us had seen up to that time. Hearing our stuff on the air gave us confidence. Bobby began to believe more in himself.”

But Bobby’s nerves showed. Playing the clown had always been his defense when he felt he was the outsider. Don says, “Before going to see a new publisher, I’d always say to him, ‘Now Bobby, just take it easy. Everything will be all right.’ But like as not, he’d jump on the piano and sing at the top of his voice. Some thought it was funny. Others threw us out. Bobby never would play it safe.”

Two who gave him a sincere hearing were Connie Francis and her manager, George Scheck. Connie was just getting started as a recording artist, but she had long been a featured performer on Scheck’s TV show, “Startime”.

Recalling their meeting, Don says, “We went out to Connie’s home in New Jersey to demonstrate a song we had written. I was with a group of other people when I noticed that Bobby and Connie were deep in a conversation of their own. I listened, and they weren’t talking about music or the record business. They were talking psychology and philosophy. When Connie recorded our song, ‘My First Real Love’, it was important, even if the record wasn’t a big hit.”

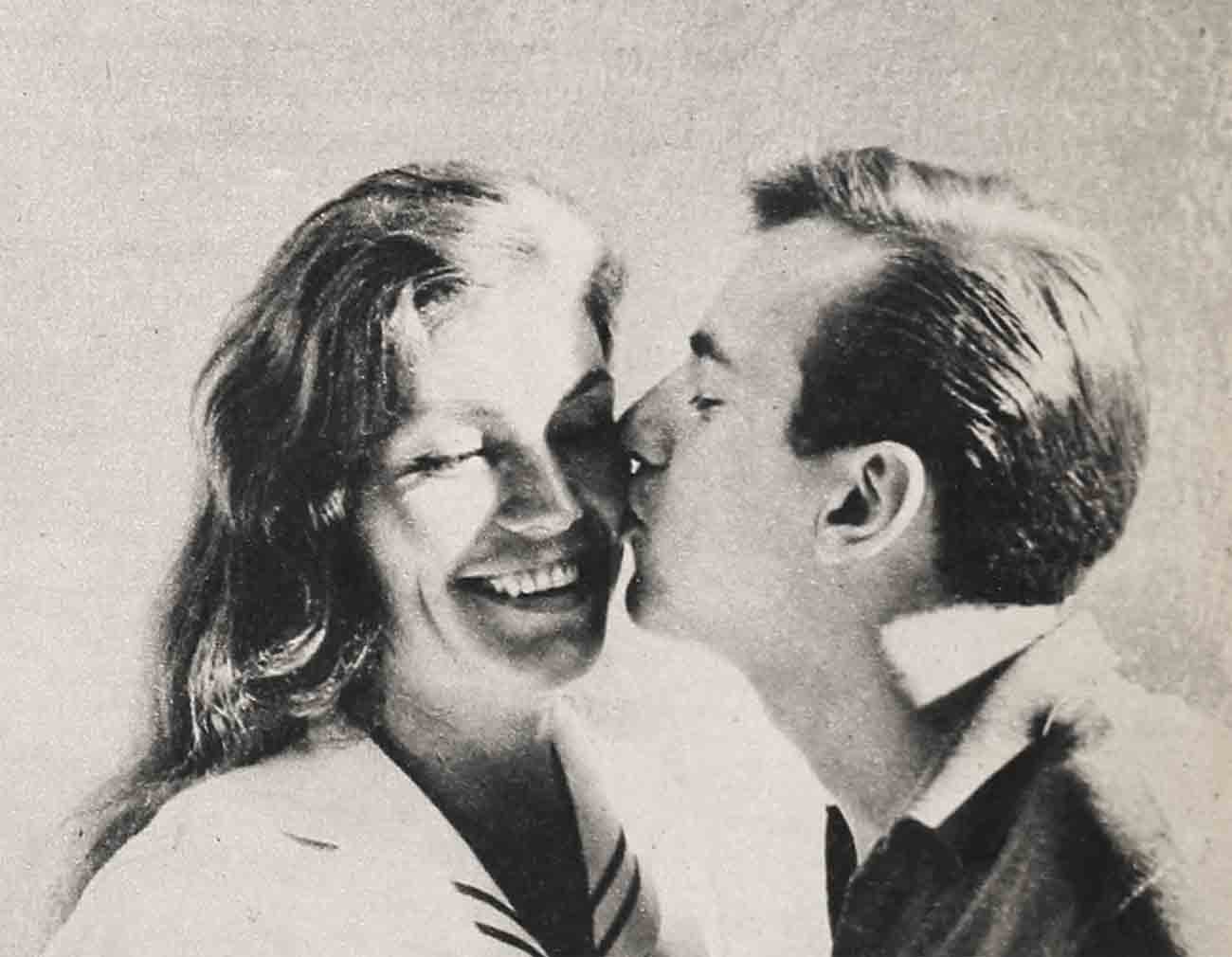

There have been many charming little stories told about the Connie Francis Bobby Darin association. Did Connie love Bobby? Did Bobby love Connie? There are those who say that for both, this was a strong attachment, but the questions are academic now, for both were very young and the romance turned to friendship before it got too serious. From it, however, both gained an understanding and a sharing of ambitions that neither had ever before experienced.

George Scheck got Bobby his first contract with Decca. They cut four records. All were bombs. Some of the sting was taken out of the failure when LaVern Baker and Gene Vincent turned tunes written by Don and Bobby into hits.

Don observes, “Even then, Bobby wasn’t happy. I realized that this guy would never be satisfied with just moderate success. He had to be a top star.”

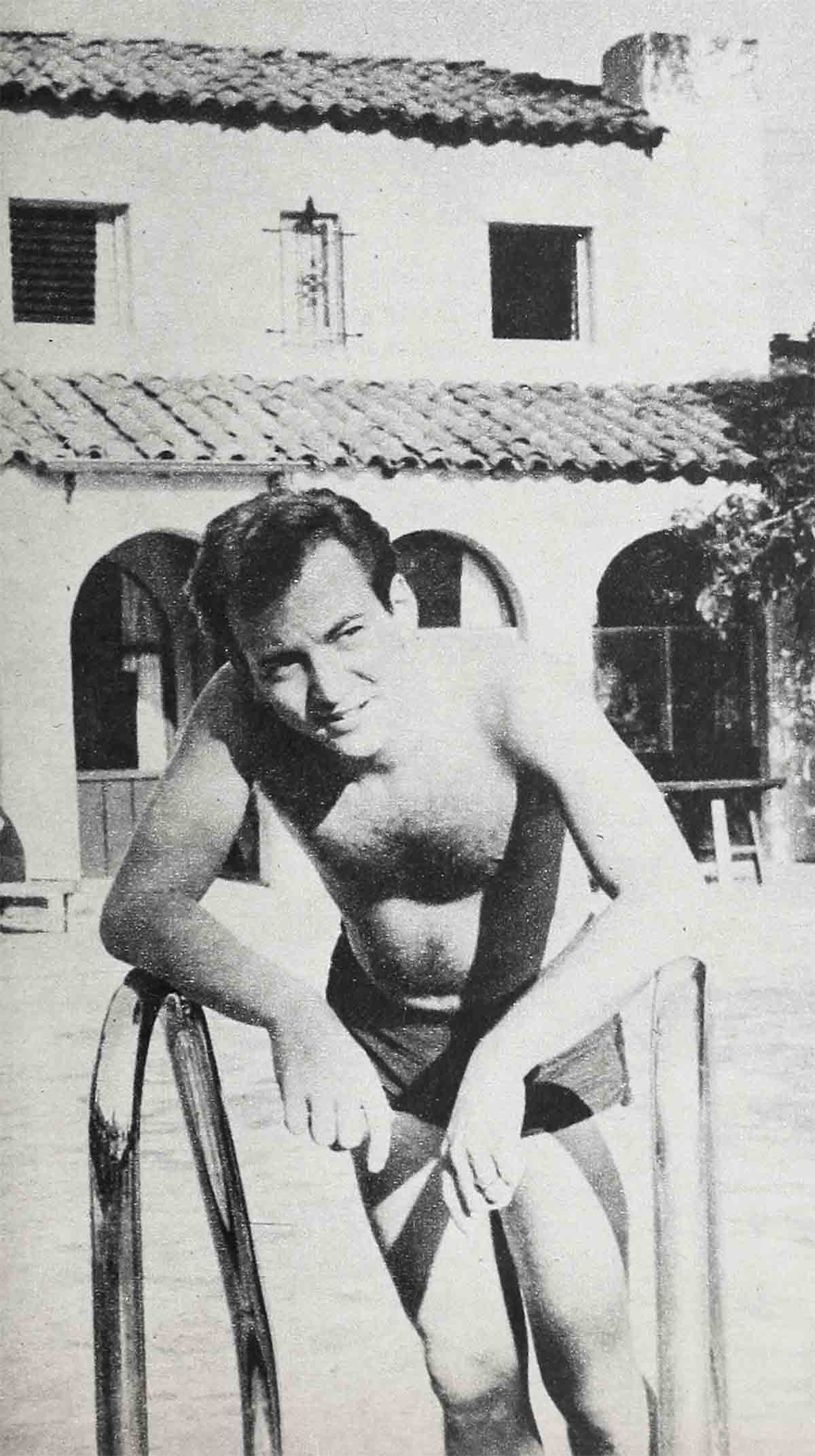

Bobby got that first hit with “Splish Splash” at Atco Records. He celebrated his gold record by buying a house at Hiawatha Lake, New Jersey, and moving his family—his mother, Nina, Charles and their children to the country. For him, this was the biggest of milestones. He says, “I had hated the places where we had lived in New York. Now I was able to do something about it. I had started to put my rebellion to work.”

There he had the joy of seeing his mother live out her last years in comfort and security. There, Nina and Charles continue to make the home that Bobby returns to between shows.

Social scientists have a saying, “Rebellion is part of growing up. Bobby Darin goes farther than that. He regards rebellion as his greatest asset.

He says, “I’m rebellious by nature. If I don’t like a thing, I won’t accept it just because that’s the way it has always been.”

Just griping about things which disturb him is no good, either, Bobby believes. “I could kick myself for all the time I’ve wasted just being sore about a situation instead of trying to change it. You’ve got to learn to use your rebellion.”

He cites two instances. “Some people in the entertainment business had me classified as a rock ’n’ roller and insisted that was all I could do. They said I couldn’t get as much as a night club booking out on Long Island and they laughed when I wanted to make an album. Well, I just made up my mind that I was going to shock the shoes off them.”

Bobby cut loose on that album called, “That’s All”. In it, he did ballads, swing tunes, standard pop songs and that offbeat number from “Threepenny Opera” called “Mack The Knife”. Some disc jockeys first played it out of curiosity alone. They wanted to find out just what kind of a fool this restricted rock ’n’ roller had made of himself.

They played it again because they liked it, and they kept on playing “Mack” until it was issued as a single and swiftly went to Number One. Bobby Darin had become an entertainer. The kid who couldn’t book into Long Island went into some of the top clubs in the country. The kid actor that no one would take for a walk-on role had his choice of motion picture contracts.

Bobby sums it up. “I said I’d show them, and I did. But to accomplish it, I had to do a little growing myself. I had to learn. That’s what I mean by using my streak of rebellion. By using it, I’ve found the place where I belong.”

THE END

—BY AMY LEWIS

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1960