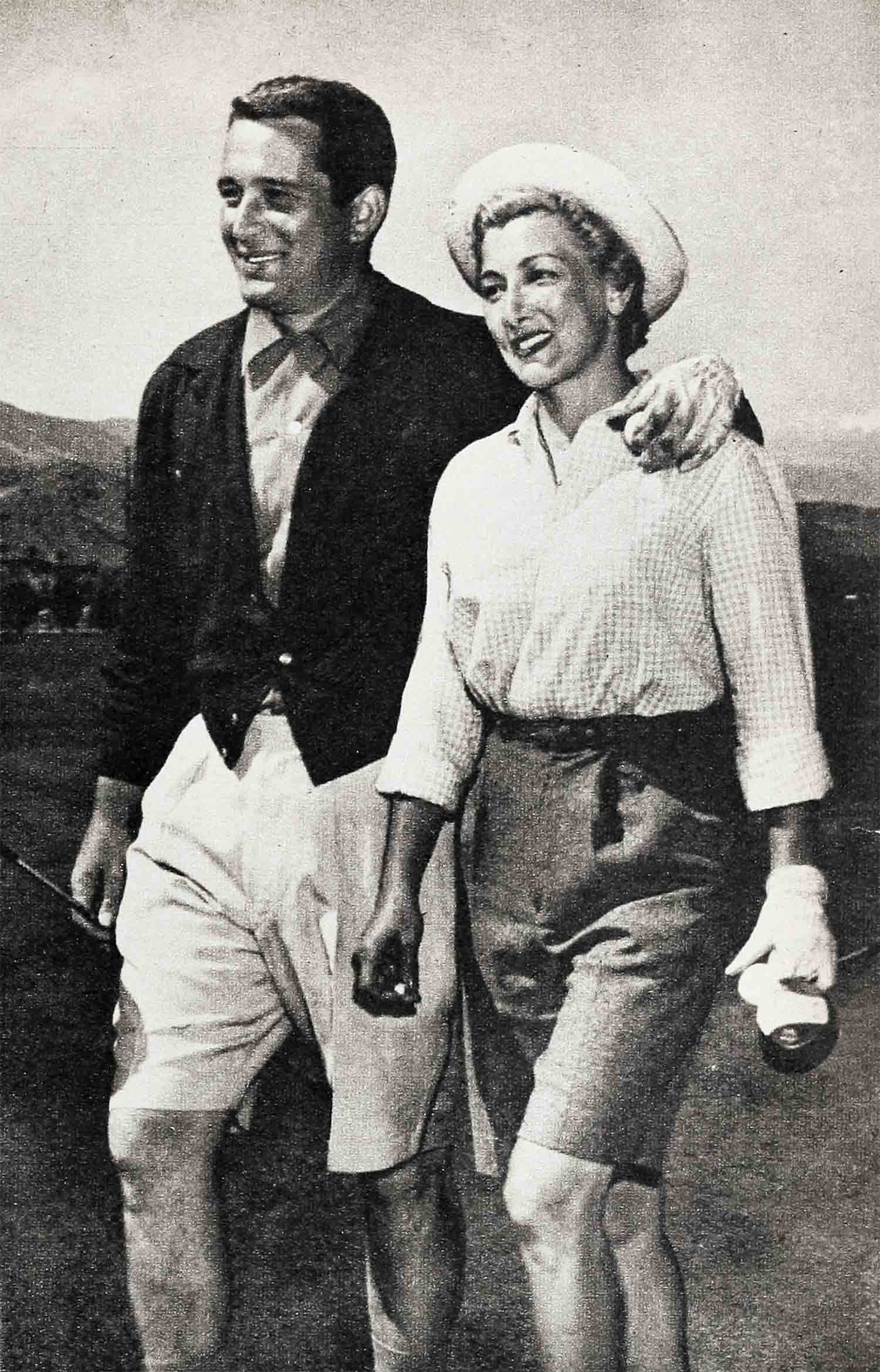

Happy 25th Wedding Anniversary Perry Como and Roselle Belline

This is a simple story.

In July, 1958, Perry Como will have been married for twenty-five years. To the same girl.

Year after year, for twenty-five years, he has created a love story that people in show business talk about—and wonder at.

And, really, it’s such a simple little story. . . .

And here is how this tale of love began. . . .

They met at a weenie roast, Perry Como and Roselle. “Everybody knows that by now,” Perry grins. “I must have Said it a thousand times. You’d call it a barbecue now. Only we said weenie roast. . . .”

But because this year is his twenty-fifth of marriage to Roselle, he clasps his hands behind his head in the familiar Como gesture, and leans back, and remembers—a little more.

He was fifteen that hot, sticky summer, and he was apprenticed to a barber. Days he learned his trade, clipping hair, applying hot towels to the soot-laden faces of the coal miners of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. He liked it well enough. A good respectable trade. But evenings—evenings were his own. Evenings he left the steamy shop, fled the sizzling streets. A friend of his had a dump truck—a glorious possession. When the sun went down and dinner was over, he would honk the horn in front of the Como house until Perry came out.

“Where to?” Perry asked one evening.

The friend leaned out the cab window. “Weenie roast. Got your guitar?”

Perry nodded and they were off. Stuffed with good Italian spaghetti, it never occurred to them to be too full for frankfurters and rolls, sauerkraut and pickles. Half an hour later, the truck jammed with high school kids, they turned off into the woods and made camp by a creek. There they were joined by other kids from other high schools, from neighboring towns. They built a fire, left it to swim, and then returned to it to dry off and toast their food. There were all kinds of kids in the crowd. There were the shy, love-struck ones who sat in the shadows, hand in hand. There were the ones who were the life of the party, howling with good humor, thrusting franks into the flames and charring them.

And a girl named Roselle Bellini who laughed and chattered and was never very far from the center of things—and who always, somehow, was the one to rescue the weenies just in time, and take into her own capable hands the rest of the cooking. Without, mind you, ceasing for one second to laugh and chatter. And a little way away, at the edge of the circle, there was Perry, his dark hair falling over his forehead, strumming his guitar and singing. One by one,

listen. One of the last to leave the gaity by the fire was Roselle—sparkling, brimming with life. But in the long, lazy evenings, it began to strike Perry that the group around him had an unfinished feeling until Roselle ambled over too, and lowered her laughing eyes, and fell silent.

Portrait of Perry as a young man

It would have surprised the good folk of Canonsburg to know that ‘that nice, quiet Como boy’ considered himself something of a hell-cat at the age of fifteen. But it wouldn’t have surprised them at all to learn that from his place in the shadows he watched Roselle Bellini and thought about her and began to fall in love with her weeks and weeks before he got the courage to ask her out.

After that, there’s nothing to tell them that could be a surprise to the neighbors—because they saw it all. They sat on their front porches and nodded benignly when the Bellini girl and the Como boy strolled by, her hand on his arm, on their way to the center of town where Roselle would draw out her weekly half-dozen books from the lending library, and Perry would pore intently over sheet music for guitar and voice.

And the neighbors happily would peer through lace curtains when the ever-useful dump truck roared down the quiet street where the Bellinis lived, and cock their ears to hear the sound of a little boy, Dee Bellini, racing upstairs to shout: “Roselle! Roselle! Your fella’s here again!” And they would joke, seeing the two of them together—Perry so quiet and slow-moving even then, Roselle so bubbly, her lips never still—they would say: “She’s the one with the barber’s temperament!” And, “I do declare—it is amazing the way opposites attract!”

Amazing—yes. But to Roselle and Perry, at fifteen, it was the most natural thing in the world. They discovered in each other a wealth of riches that neither possessed alone. To Perry, Roselle was a princess out of a fairy tale—a princess in bobbed hair and middy blouse—utterly charming, utterly gay, drawing him out of himself, awakening his sense of humor, making him laugh, making him sing. And to Roselle, accustomed to the cheerful racket of a big house full of five children, there was a depth of peace and contentment in being with Perry that she had never known before. He made her a little less frantic, gave her time to look at herself, to think about life and what she wanted from it. To channel her tremendous energies and point them in one direction. A direction marked: Perry Como—this way.

They knew very soon that they were in love.

Love in a small town

What happens to a boy and a girl in a little Pennsylvania town when they fall in love? Well, mostly they wait till they get out of high school, and then, if the boy has a trade, they get married and settle down. And surely no one ever had a better chance than Perry and Roselle to do just that. In their last year in high, Perry worked after school in the barber shop, earning pocket money, perfecting his skills. Roselle would wait for him until closing time. Then the evenings were theirs to spend together. By the next year, seventeen years old and out of school, Perry was an incredible, unbelievable success. He had a shop of his own now, and the miners poured into it as if it were a saloon instead. The neighbors had been right—the Como boy wasn’t as talkative as folks expect a barber to be. But they had forgotten his other talents—and the fertile imagination of the Bellini girl.

Perry Como was the only singing, guitar-playing barber in Canonsburg—and possibly in Pennsylvania!

His take-home no longer amounted to pocket-money. It came to a hundred, a hundred and a quarter a week. Big, big money in 1929. Enough to remove any financial burden from his parents’ backs. Enough to treat Roselle to steak instead of hot dogs, take her dancing instead of swimming. Enough so that when the Depression hit, devastating Canonsburg as it did the whole country, there was a backlog to carry the Comos through. A profitable business, indeed.

So why weren’t they married? 1929 came and went, 1930, ’31, ’32. Pennsylvania got back on its feet. Roselle was no longer needed to help at home. Everything was perfect—except for one thing. Roselle, patiently getting Perry’s dinner in his mother’s kitchen and then watching it

get cold on the table because Perry was late again, wasn’t sure that this was the life for either of them.

Too much work

When Perry hired first one and then another assistant, she regarded it less as a sign of prosperity than of his being over-worked. No amount of big money could make up for the tired rings under Perry’s eyes. This new life had everything—except fun. Except the satisfaction a woman feels knowing that her guy is doing what he loves to do, what is right for him. And what was right for Perry? Who knew?

Ask Dee Bellini, Roselle’s little brother, now grown-up and an important member of the Como Enterprises, and he’ll tell you—“Perry? Why, I wouldn’t say it was a case of Perry’s being worried about becoming a professional singer. It was more—he didn’t know if he was a singer!”

Turn to the official biographies, and you are told that Perry’s friends urged him to audition for the Freddy Carlone band on a vacation in Cleveland. That as a joke, Perry did it. That in the same lighthearted spirit he gave up, having won the audition, $125 a week at home for $28 a week and a future of one-night stands. But read between the lines. A young man in love, wanting to get married, makes that kind of break for only one reason: his girl wants him to, his girl knows that deep down he wants to do it. That was spring, 1933, when Perry left with the band. In July Roselle took a bus to Cleveland to spend a day with him.

There, she looked for herself at what Perry had described with such worry: the sort of barren, cheap hotels he lived in now, the bus he traveled in with the band, the meagre amount of groceries that $28 would buy. And there, the girl who had turned down comfort and tranquility at home with the joyful knowledge that this was right, this was fun—there she married her guy.

The next day they went back to Canonsburg. While Roselle went home to tell her folks and pack a bag, Perry went to his house.

Look, Ma

“I walked into the kitchen, and I said, ‘Ma, I’ve got something to tell you.’ And she took one look at me and said, ‘You don’t have to tell me anything. I know. You got married.’ Happy? I guess next to Roselle and me, she was the happiest person in the world. Why not? Roselle was like a daughter to her.”

With rice tumbling out of their hair, they rejoined the band. And for three years the Bellini gaiety, the Bellini laughter brightened buses and cheap hotels and hamburger dinners, while Perry built up a name in the Cleveland area. And then one night in 1936, he came home with news. The Ted Weems band wanted him—at a stupendous $50 a week. It was a bigger band, a bigger chance. But—if life had been rugged with the Carlone band, it would be a hundred times more so with Weems. Weems played the whole country.

“How wonderful!” said Roselle, starting to pack . . . packing for the next seven years.

“And in all that time,” people asked Perry, “didn’t she ever complain, ever want to quit?” Perry would roar with laughter. ‘“Roselle—complain? Listen, you don’t know my wife. I mean—this is a woman. She doesn’t let you know every little thing that goes on through her mind—she laughs. She enjoys. No, she doesn’t complain. I was the one who worried.”

The Weems band was in Chicago when their first child, Ronnie, was born. That was 1940—seventeen years ago. Most girls in 1940 didn’t have babies one day and spring out of bed to care for them the next. Usually, their folks were there to help out for a while, to be at the hospital, to take over the housework. But Canonsburg, Pennsylvania was a long way from Chicago in 1940. Roselle had her baby without benefit of family—and spent her time telling a frantic Perry that it was “all right, honey,” while he agonized.

We didn’t worry . . .

And when, three months later, the Bellinis were finally able to get together the time and the requirements for a good-sized trip to see their new relative—everything was fine. The long engagement in Chicago had given the Comos what was almost a home—an apartment with a baby in it. Looking back now, Dee Bellini says, “Sure it was rough some of the time. They didn’t have everything by a long shot. But Perry—he was singing. And Roselle was always an adventurous girl. We didn’t go away worried from our visit to them. They were having a ball.”

They didn’t know what was to come. They might have worried if they had. For Ronnie was scarcely six months old when the next big break came along. The Weems band was to play New York—the Strand Theatre. And on the same bill was Ann Sheridan, The Oomph Girl. This was big-time—the biggest. This was the time for Perry Como to be heard in New York. And he came home to the apartment and looked around at the clutter of baby things, the bassinette, the crib, the drying diapers—and shook his head, telling Roselle about it.

“We can’t take a baby in a bus. . . .”

Roselle studied him for a moment. “Well,” she said slowly, “I suppose Ronnie and I could stay here—”

Perry’s head jerked up. They had known each other for thirteen years, been married for seven. And they had been together for all of them. “Are you nuts?” said Perry. “No soap. I’d rather not go.”

It was the answer Roselle had been wanting. Having gotten it, she discarded it and settled down to business. She took out a piece of paper. “Listen, honey, I have an idea. . . .”

The next day Perry bought a car. He and Roselle ripped out the back seat. Long before Nash thought of it, the Como’s had the first auto in the country with a bed in the back. And on that bed, tucked in securely, safe from bumps, cooing cheerfully, Ronnie Como rode to New York with his parents. And from New York to the midwest, and back to Chicago, and to California and Texas. Perry drove, and Ronnie gurgled, and Roselle heated his bottles on the hood over the boiling engine. They crossed the desert, and Roselle piled ice into insulated bags and air-conditioned the car for her husband and baby. And in every big city in the country, Ronnie Como was pronounced by doctors: thriving, growing, happy.

What a little boy needs

You won’t get Perry Como to talk about what finally called a halt to the ball. Maybe it was because in 1942 Ronnie was two years old, and a two-year-old boy doesn’t need a bed even though it’s a comfortable one that’s rigged up for him in the back of a car—he needs a yard to run in, friends to play with, a house in which to put down roots. Maybe it was because the Ted Weems band was breaking up, and a married man with a family needed security. Or maybe it was simply because one day he caught Roselle looking at a copy of House and Garden—and for once, her eyes weren’t laughing. It doesn’t really matter what it was. Whatever the reason was, in 1942 Perry Como started looking for another barber shop to buy in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania so he could give his wife and child what they had not had, what for love of him they had never asked for—a home. And while he was dickering over terms for a likely-looking location, while he was practicing his shaving stroke and trying to remember what it felt like not to sing—the miracle happened. CBS radio wanted him for a sustaining show at $100 a week, and RCA Victor wanted him to make records. It meant that they could live in New York, rent a house, put down roots—and it meant that Perry could sing. It meant that luck was with them, that miracles still happen—or maybe it meant that the world is not entirely topsy-turvey after all, and nice people do sometimes come out on top.

It has been quite a few years since Roselle Bellini Como has had to darn socks on a bus or heat baby bottles on a car motor. Ronnie, the well-traveled infant, is away from home again now—in Notre Dame. Roselle and Perry have two other children, David and Terry, but they are growing up, not in hotel rooms but in a beautiful home in Long Island—a home to make up for all the years of homelessness. And every night a good-looking, exceedingly rich, exceedingly popular forty-ish man comes home to her there.

Perry sums it up

Ask Perry Como what Roselle means to him after twenty-five years of marriage. And in this, his twenty-fifth year as her husband, he will tell you, “Oh—I can’t give you an answer, just like that. There are lots of things. Like—she takes care of me. Of everything. I leave in the morning and I know when I come home at night—things will be the same—good, quiet—the way we like them. She does that. She can do everything—the marketing and the cooking and bringing up the kids—and do it well.

“And when I come home—well, after twenty-five years, we don’t tell each other every tiny thing. She doesn’t tell me how many times David didn’t come when she called, and I don’t necessarily tell her which camera loused up which scene today. But—we’re together. We sit and talk or we watch television—it’s good to sit quietly with someone you love, to be together. What can I tell you about her? She’s a strict mother. She says no, and the kids know it’s no. But loving—well, Ronnie’s away in college now, you know. And he wrote home he caught cold. Well—my wife practically ate her heart out over it. Who’s going to give him his aspirin? Who’s going to see he covers up his throat? I mean, what can I tell you about a woman like that? I’ll tell you this—she’s there. That’s it about Roselle. She’s always, always there.”

And always, always will be. For this is a woman who doesn’t need what she doesn’t have to keep a man—even a famous man, to make a marriage last for twenty-five years. A woman who gives abundantly of two things: love, and herself.

We said at the beginning this was just a simple love story. That’s all it is. And as such, it gets a simple ending, but in this case an ending as true as true can be. . . .

And so they lived happily ever after.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1958