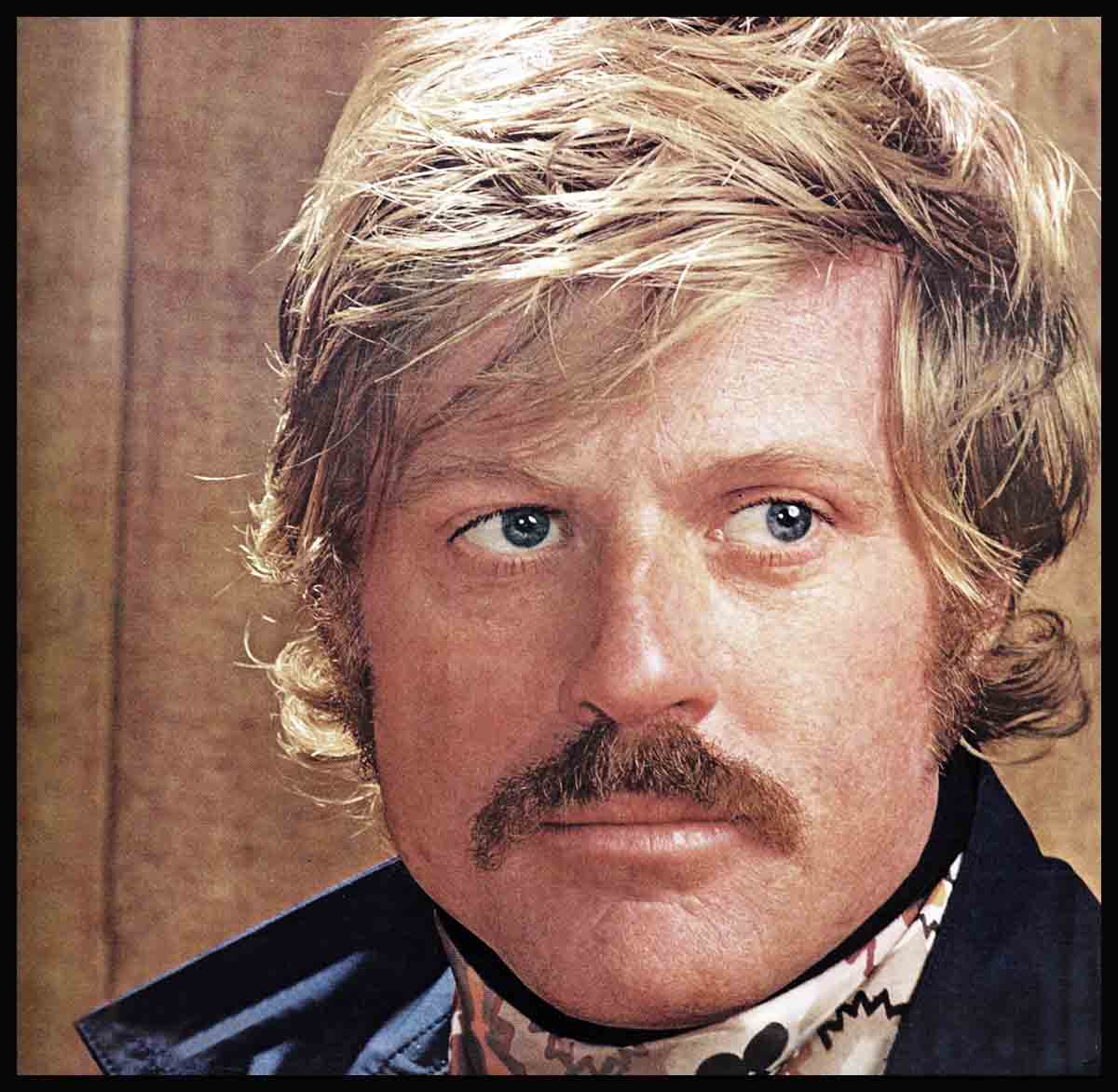

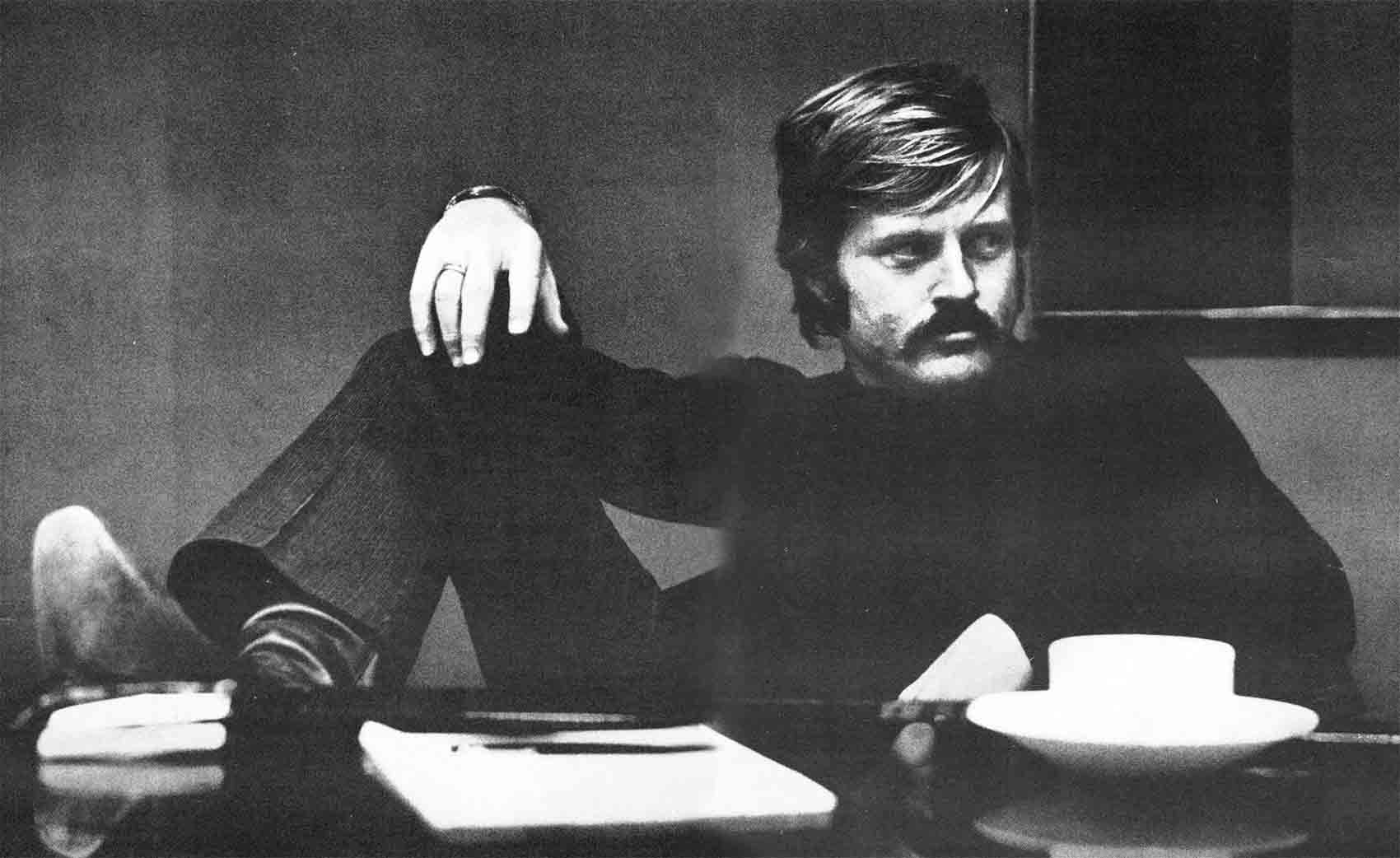

Robert Redford Riding High

Since the beginning of his career over 10 years ago, the movie industry believed in Robert Redford’s future. So, for that matter, did Robert Redford. The problem was that they could not agree on what the exact nature of that future should be. To settle the argument, Redford stayed stubbornly off-screen for two years, and when he emerged recently as the Sundance Kid (in collusion with Paul Newman’s Butch Cassidy), it was evident who had won. The film is one of the season’s mightiest hits and he is now contending with a slew of promising new projects. Two more films are already in release, Downhill Racer and Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, both critically admired and potentially profitable. Some people think he stands a fair chance of becoming one of those rare stars who sums up, all by himself, the spirit of his time—as Brando did for the ’50s, as no one quite did for the ’60s. In any case, Robert Redford is riding very tall in the saddle just now. And, as is his manner, very easy.

Why it isn’t easy to be a friend of the Kid

As I should have known, Redford finally has me right where he wants me. For years I’ve been telling him there are good journalists as well as lousy ones, that someday someone would put him down on paper, not an image. “No way,” he would gloom, his eyes going slitty, his face clenching as I know it does when a press agent towing a journalist heaves alongside.

So, of course, the challenge became irresistible, and here I am. The deadline is 24 hours off, the space, naturally, is not all I had hoped for, and I have about 50 pages of false starts piled up on the desk next to me. It now seems unimaginable that I actually volunteered for this assignment. I’ve always known better than to write pieces about people I know. And if I were going to start doing so, I certainly wouldn’t begin with the Scarlet Pimpernel. Now I’m beginning to hear his laughter, half sympathetic, half mocking: ‘“Really looking down the barrel, aren’t you, Dad?”

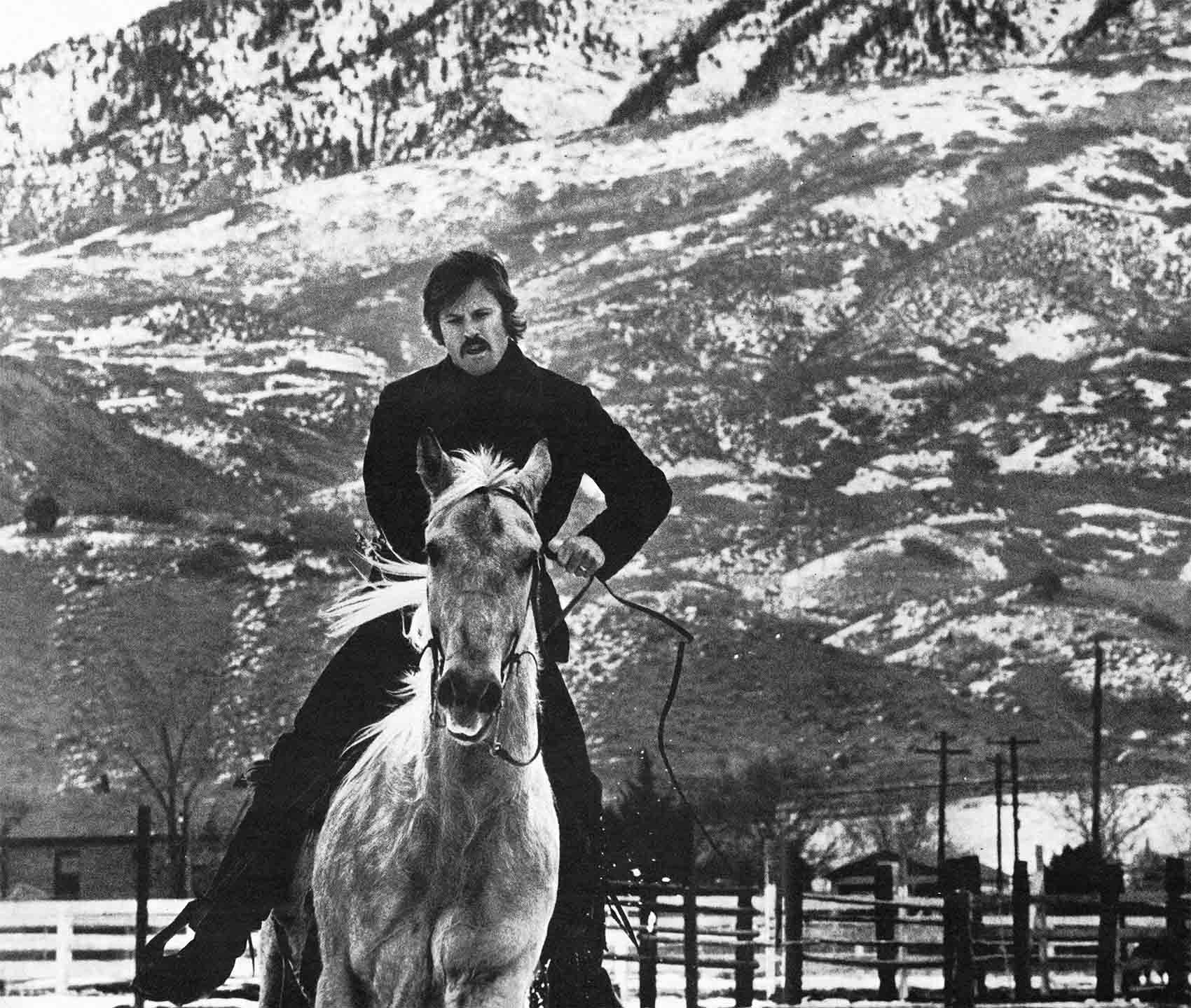

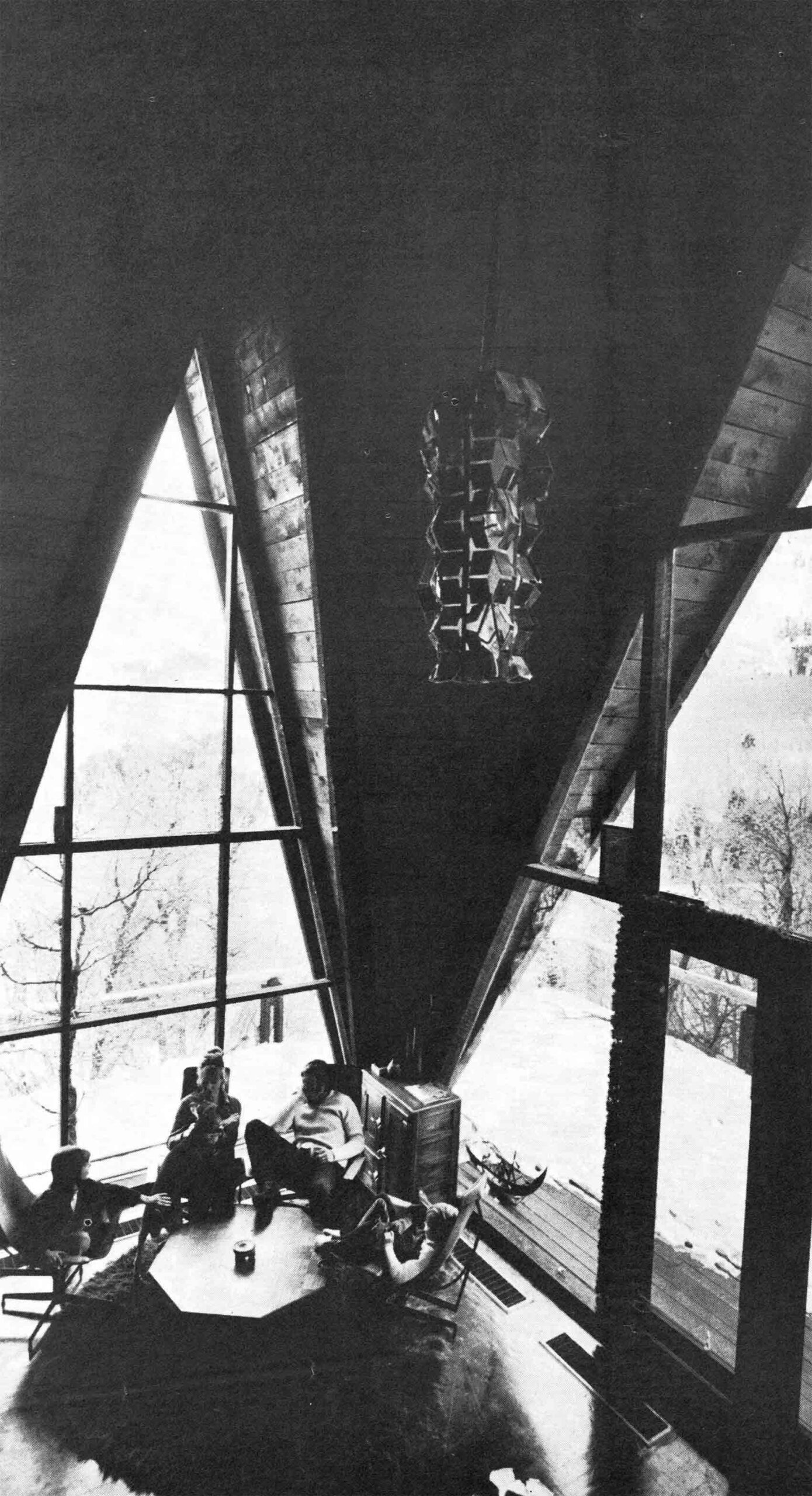

Yes, dammit. But come to think of it, that’s the basic thing about Redford. Just standing there in his socks, just existing, he goads and tempts and bugs and dares you into ventures and adventures you would normally not dream of undertaking. Looking down my particular barrel, I’ve been consoling myself thinking about all the other friends he’s put in similar spots. There’s Hal Holbrook, the actor, placed uneasily atop a horse at Redford’s Utah place and very nearly getting crushed when the animal (who, like all of Redford’s string, knows a dude when he sees one) decided to roll over on top of him. Then there’s Stan Collins, one of his partners in Sundance, the ski lodge down the road, bucketing out of control up a mountain trail on Redford’s motorcycle and cracking a few ribs when he involuntarily dismounted. And let us not forget the very nice phone call one of his producers made to thank Redford for his weekend in Utah. He expected to be up and around in just a few days and the hospital had just told him his partner, who had joined them on an eight-hour ride through the snow, would probably be discharged in a day or two if there were no further complications.

The casualty list is endless and if you are Redford’s friend you learn to accept the inevitability of a certain amount of pain and humiliation. It is never really his fault. He surrounds himself with all this terrific stuff—skis and water skis, motorcycles and Ski-Doos, horses and racing cars—and he is so competent with all of them, so obviously has fun with them and so obviously wants you to share his pleasures that you just have to try.

He is, of course, the soul of sympathy after disaster strikes, instantly turning accident into anecdote in which victim becomes hero. A comic one, of course, but center stage for all that, and esteemed for avoiding the only truly reprehensible crime in Redford’s book— “taking the pipe.” At the very least it consoles you to remember that Redford himself is the cheerful anti-hero of many of these tales: the time he drove the Ski-Doo over the cliff, the time the motorcycle flipped out on him, the time the boat he was hauling came unhitched and appeared amazingly in front of his car, the time the accelerator on his Porsche got stuck at floorboard level as he gunned down the mountain road. He tests himself as he tests his friends—to see if the cool is still there. And the quickness. And the sense of fun.

Does all this suggest his idea of pleasure, not to mention his system of values, has not progressed much beyond adolescence?

I hope so. And I hope no one thinks it’s a bad thing. As individuals, the best value system we ever have is when we are kids, when honor and integrity are everything and we have the strength and the will—and the anger—to defend them. I’m pretty sure Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is such an enormous success because Paul Newman could not resist (any more than anyone who likes Redford can) being drawn into a re-creation, however temporary, of an adolescent relationship with him, both offscreen and on. The movie has a lot of flaws, but right here, at its human center, it rings true as true can be. The horsing around, the readiness to try new gags, new places, adventures, the easy, mostly trusting way kids have with each other. That truth is what has given it its large, loyal audience. And it is what has finally made Redford the star everyone has been predicting he would be for a decade.

Actually, one might have predicted this movie would be the big one for him. For long before he played the Sundance Kid he was in the habit of referring to himself, in his many self-satirical moments, as “the Kid.”

It is said that the reason adolescents put us uptight is that they remind us of “the life unsquandered.” Redford is good at that. He even does it to me and I’m only three or four years older than he is and don’t especially think of my life as squandered. He does it to others who have no better reason than I do for feeling bad about the way things are going. Among his friends there is a ’steady grumble of crocodile concern about him. He’s working too hard. He’s not working hard enough. He is self-destructive. He is self-indulgent. He misses planes. He’s always late for appointments. He shows up in fancy restaurants without his wallet or without a necktie. (Does he own one? I can’t honestly say.) No one, it will be noted, complains of any real hurts. He is, in fact, a singularly loyal, generous, unobtrusive and undemanding friend. All he ever does (without meaning to) is remind you of pleasures postponed, risks untaken, life not lived quite as fully as you intended when you used to think of yourself as “the Kid.”

“The only trouble with Bob,” says a lady who knows him, “is that sometimes he’s just too dazzling.” What she means is that there are times when it is simply intolerable to have him breezing in and out of your life (“Hiya, Chief, so long, Ace”) passing through from someplace he makes sound marvelous to someplace he will make sound wonderful. These moments of envious bedazzlement generally occur when you are in a temporarily weakened condition— when all the children have been on penicillin for a week and aren’t getting better, when your accountant has just called to tell you your tax bill was a little stiffer than he had originally estimated. In such dreary contexts Redford stands there with his trim, tan, healthy exterior wrapped around a nervous system entirely innocent of booze, cigarettes and Miltowns and something inside you harrumphs disapprovingly. Damn fool ought to watch his step.

It makes you feel for the people who have to do business with him. All your typical movie magnate has ever wanted to do to Redford is press an inordinate amount of money on him for doing something he’s good at and even sometimes likes to do, namely act in a movie. Whereupon the mogul is informed that Redford has taken himself and Lola and the children to Europe for a few months, leaving behind only the sketchiest instructions as to when, how and where he is to be reached. Whereupon the mogul starts imagining him, all shaggy and sloppy, in some Greek fishing village where they don’t have a telephone and the last time they saw a movie was when somebody packed The Birth of a Nation in on muleback 40 years ago and nobody understood it. Whereupon he starts thinking about how the telephone is like permanently grafted to his ear, how nobody ever lifts the film cans off his back and how only yesterday he actually believed an item in the Hollywood Reporterthat his own flacks planted. Experiences of this kind can lead to very dark reflections about squandered lives. And to a degree of irritation with the person who causes them. Damn fool ought to watch his step.

To which Redford replies, “I don’t like working a lot and I don’t really respect the profession, the business of being an actor. I have no need to be a star. All through my career people have been telling me, ‘In three years you’re going to be the biggest star in Hollywood.’ I’ve got all these plaques naming me the star of tomorrow. But I never did believe it.”

The words are the stuff of fan magazine interviews, but Redford has stuck to them. I watched him do it for two nonworking years and there was neither stupidity nor bravado in the performance. Just a stubborn sense of who his best self is. He was almost as hot then as he is now, for he had just repeated on film the role he created on Broadway in Barefoot in the Park. Scripts piled up and in due course he chose a thing called Blue. A week before its start date, he walked out on it. Unforgivable, especially since money had changed hands. Suits and countersuits were threatened. The people who are paid to fret over him did a regular production number, in which the rest of us joined in. I thought maybe he was making up his mind about the whole movie star thing. I was wrong, but not as wrong as the people who thought he was just being childish. What he was doing was redefining, in terms that would suit him, the nature of stardom.

He was entirely unmelodramatic about the whole thing, and remains so in retrospect. “People said I wasn’t tending my career when I walked out on Blue and turned down all that other stuff. I thought I was.” Until then, he had been choosing parts, not films; now he was insisting on having something to say about the property surrounding him onscreen. “They throw that word ‘star’ at you loosely, and they take it away loosely if your pictures flop. You take responsibility for their crappy movie, that’s all it means. So what I said was, since you say I’m responsible if my name is above the title, then give me responsibility. That’s all.” One loves Redford, among other reasons, for the enemies he makes. I have a single, controlling image of Redford during the holdout. Before it began, Lola had scheduled a complete renovation of their New York apartment, thinking he would be out from under foot, making a movie someplace or other. But, of course, he wasn’t. Most of the furniture disappeared, workmen appeared and started tearing down walls. A fine coating of plaster dust settled over all. In the midst of this chaos Redford perched on one of the few remaining chairs, snapping his brisk putdown into the ever-busy telephone. He was going broke that way, but he didn’t stop until he got what he wanted.

He didn’t want anything outrageous or elaborate. He didn’t want to do Oedipus at Colonus as a musical or Hamlet as a western. He had, however, acquired a vision—that’s a critic’s pretentious word for it, not his—of man, of this nation (“Oh, wow,” I hear him saying), and he wanted to put some of it onscreen, that’s all.

His vision is one of self-creation. His background is suburban Los Angeles, middle-class striving and it was not good enough. Neither were sports, except as an outlet for unused energy and competitive instincts. By the time he was 15, he and his brother had identified themselves as “soldiers of fortune.” They were good at things like sneaking into movies, indeed anything that had a No Trespassing sign on it. Once they climbed the tallest structure in Westwood, the sign for the Fox Village Theater, learning it was “a big, big feeling to be on top of something.” But unscrewing the light bulbs in the X was an anticlimax.

College (the University of Colorado on a baseball scholarship) was worse. Redford lasted a year, most of it spent on the road, not exactly a Dharma Bum, but discovering what Kerouac and all the others who tried to poeticize this experience in the ’50s discovered: that a car hurtling through the night on a straight stretch of prairie road is a kind of mobile Magic Mountain for the poor man—silent, detached, a place to discover yourself.

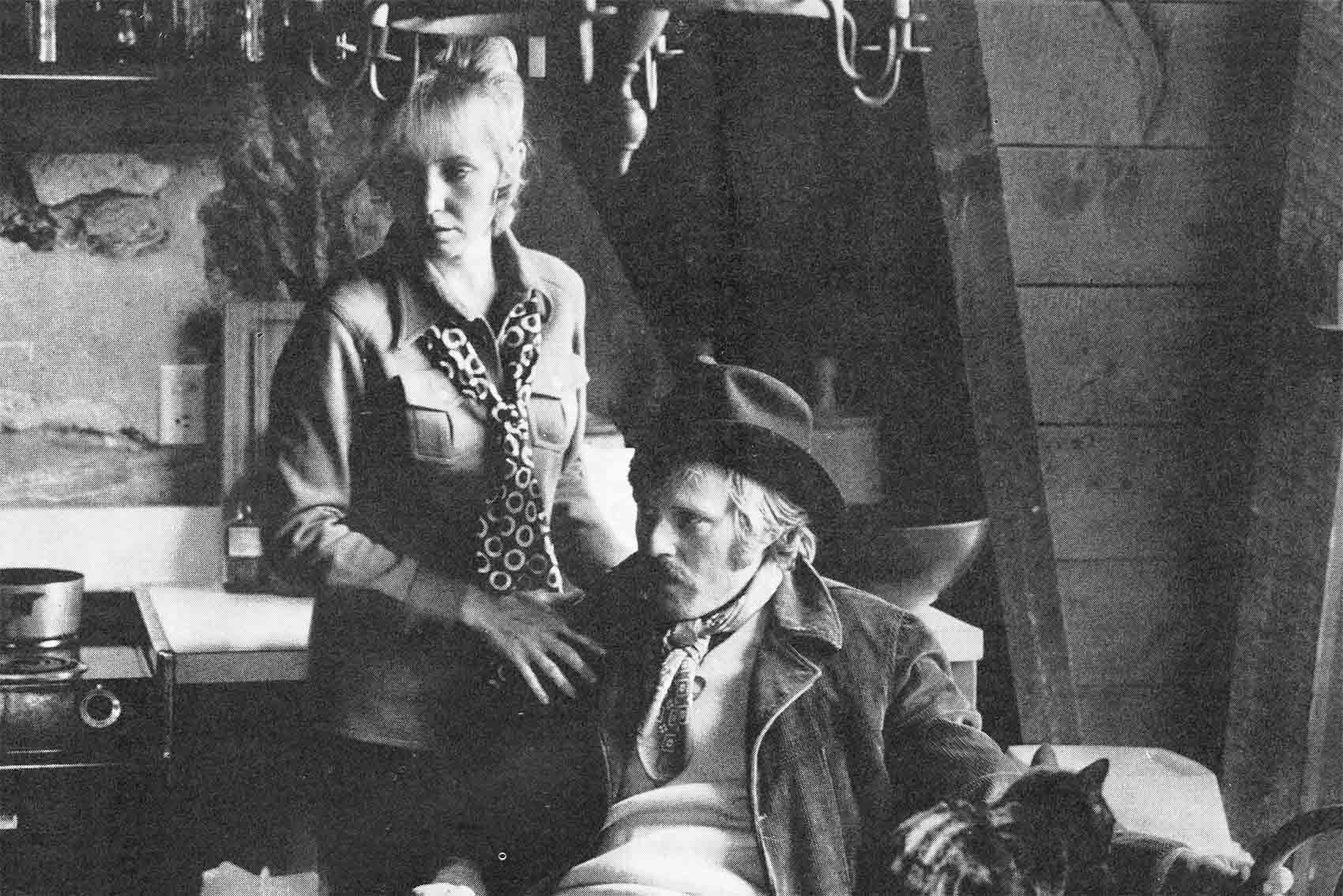

Redford had always drawn and painted—“the only way I could express myself”—and someone at Colorado told him he ought to try Paris, the art schools there. He earned the money for the trip in the L.A. oil fields, stretched his Yo-Yo string to Europe, snapping back a year later broke. He was back in the oil fields, vowing to get out and never again work at a time-clock job, painting gloomy pictures— “eyes gouged out, blood dripping”—when he met Lola. A Mormon, good, small-town, traditional, positive virtues and values. She was in town for the summer, sharing an apartment in Redford’s building with girl friends from Provo. One night she and her friends came giggling in search of wickedness to the crazy cave of Redford and roommate. They asked to see his paintings, but Lola was the only one who really looked. I once asked Redford what he thought was going to become of him in these years. “I didn’t know,” he said, “but I was always sure I was going to come out all right.” It is the right Mormon answer, and since that faith was built on energy and thrives on good old-fashioned free enterprise and competitiveness and knows all about wandering in the wilderness, they turned out not to be an odd couple at all.

By the time they married, Redford was studying acting. He had enrolled in the ANTA school in New York, thinking he might like to be a stage designer. He moped through a required acting course, daring the teacher to involve him. One day the man somehow angered him and Redford did a freak-out interpretation of a scene from All My Sons. He ran around the room screeching his lines, and slobbering, and pulling people out of their chairs. For a climax he did a flip off a ballet barre and jerked the instructor out of his chair to yell the final lines into his ear. “Fine,” said the instructor. “Now let’s see you do it again.”

He did. “Everybody’s got a bear in him,” Redford says mildly. “It’s all in getting him out and then controlling him.” He slips the bear out so smoothly and coolly now that you never see it happening. Lola says she has never been aware of his learning lines or studying a part. This is all I’ve ever heard him say about technique: “I just plunge in.” I think he sees a part as he used to see movie theaters—as something to sneak into. The fun is all in not getting caught, in seeming to belong where you know you don’t.

Kid stuff, in short. But the Kid is not really a kid anymore. He stopped being one—full time, anyway—somewhere out there on the road. If he were still just a kid, acting might have absorbed him, defined him as it does so many. It is, after all, good work for simple, golden boys.

But you act parts. And parts are not wholes. And people possessed by visions do not settle for parts of them. The kids, who dig him, think surely he must speak for them—cool, anarchical and, as the magnates say, a rebel. I don’t think he is—not the way they mean. He is less a now man than a then man, a romantic, radical individualist of the kind that 19th Century America produced and celebrated.

So Sundance, who dies precisely because he is such a man, appealed to him. The sheriff in Willie Boy, trying and failing to be such a man, interested him. But his own production, Downhill Racer, about a highly individualistic skier obsessed by the need to win but to do so on his own terms, without ever emotionally joining his team—that’s pure Redford. Winning requires discipline; the spirit requires freedom, and Redford is caught, like the downhill racer, in the tension between those contradictory demands.

Since then, he’s made Little Fauss and Big Halsy, about a pair of disorganized motorcycle racers. Now he’s trying to get a movie going about rodeo riders. He is, after all, a citizen of this century and so knows that absurdity is tangled up in that fascinating contradiction that, by fascinating him, helped create him. Which is why he goes to the fringe sports, where the radically free men, reckless and anonymous, compete for valueless prizes, where winning is perforce its own reward and therefore wonderfully pure, untainted.

Heavy. Very heavy. He hates analysis. It dulls the dazzle, slows the fast, instinctive footwork. So go out thinking of him one day when he was learning to ski. He got going too fast, was looking around for a convenient place to wipe out, when he hit a mogul and, flying through space, caught a glimpse of his shadow. His position, he discovered to his delight, was textbook perfect. “I looked so great,” he says, “I decided I had to keep going.” That’s the Kid for you. Or all he really wants us to know about him—that he’ll keep going, looking great.

—BY RICHARD SCHICKEL

Photographed by JOHN DOMINIS

It is a quote. LIFE MAGAZINE MARCH 1970