It’s Fun To Be Bracken

If the art of acting is pretending you are somebody else—which isn’t a bad lowbrow definition— then Eddie Bracken, the village cutup, is a great actor. If you saw “The Miracle Of Morgan’s Creek” you were persuaded at one time without knowing it that Eddie was Betty Hutton, and at one time he was able to make people believe he was the late Franklin D. Roosevelt. Being either one of these characters would be quite a career—but in addition Bracken is Bracken, and this is the most fun of all.

Eddie began as a public performer at the age of four by gagging around, and now, at the age of twenty-four, he has made a fine thing of funny-business. Although he does not yearn to play Hamlet—not yet, anyway—he has some serious plans for himself, for he can remember when he was all washed up in the movies at the age of nine.

Bracken’s first gag was pulled on a sister at Our Lady of Mt. Carmel School in his native Astoria, New York, which you can get to by subway from Ne w York City if you could ever think up a reason for going to Astoria. The school was putting on a show and needed a singer. When a sister asked for volunteers the small Bracken said he could sing.

“Let’s hear you,” said the sister.

So Eddie gave out with:

“Mary had a little lamb;

She also had a bear,

I’ve often seen her little lamb

But have never seen her bare.”

A fine thing to pull on a sister in a parochial school—but she liked the performance and put the lad in the show with some more elevating words to sing. Bracken can’t remember what they were, but they started him singing all over town. He warbled at the big annual pageant of the Knights of Columbus in the Palm Garden in New York. His ability as a chanter kept him from going beyond the eighth grade, for at this stage he decided that a clamoring public deserved all of his time.

Actually, the public hasn’t done a lot of clamoring until recently; but now it wants to see Eddie in anything he does, from personal appearances in which he imitates a ball player to appearing in Preston Sturges movies, in which he impersonates the luckless oaf we are all glad we are not.

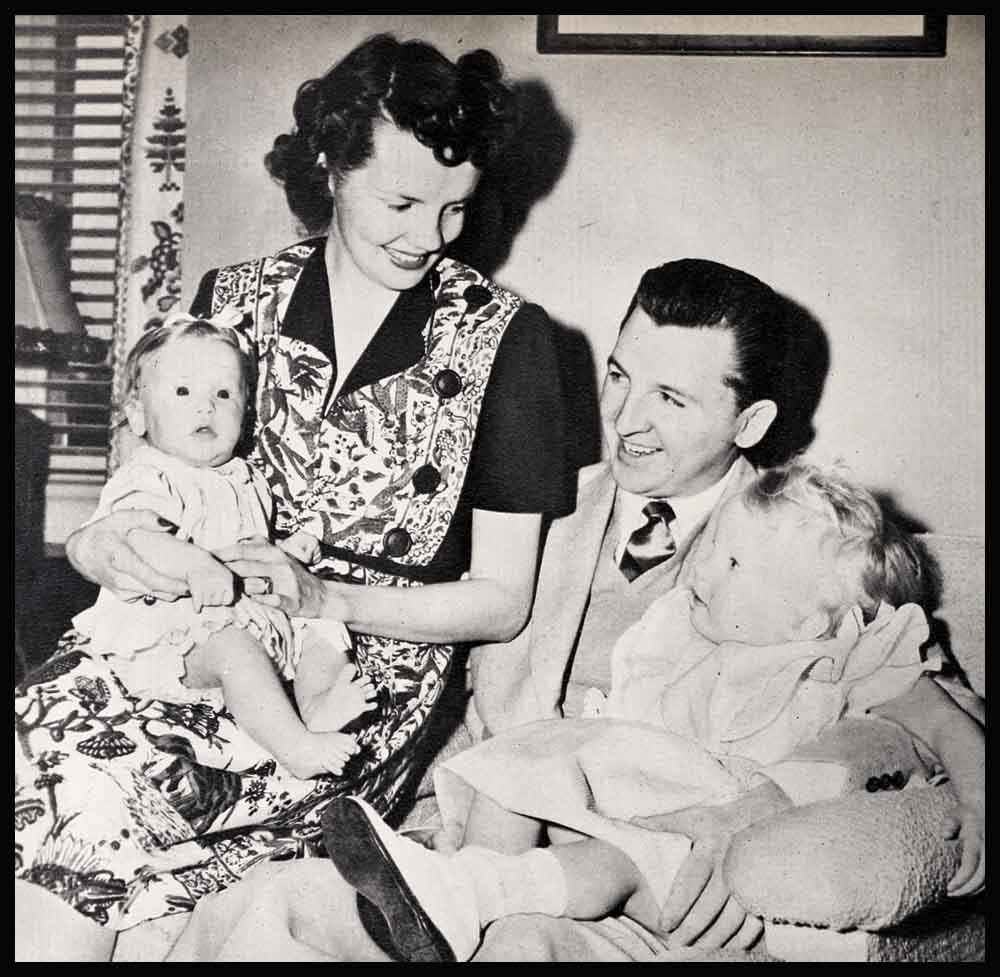

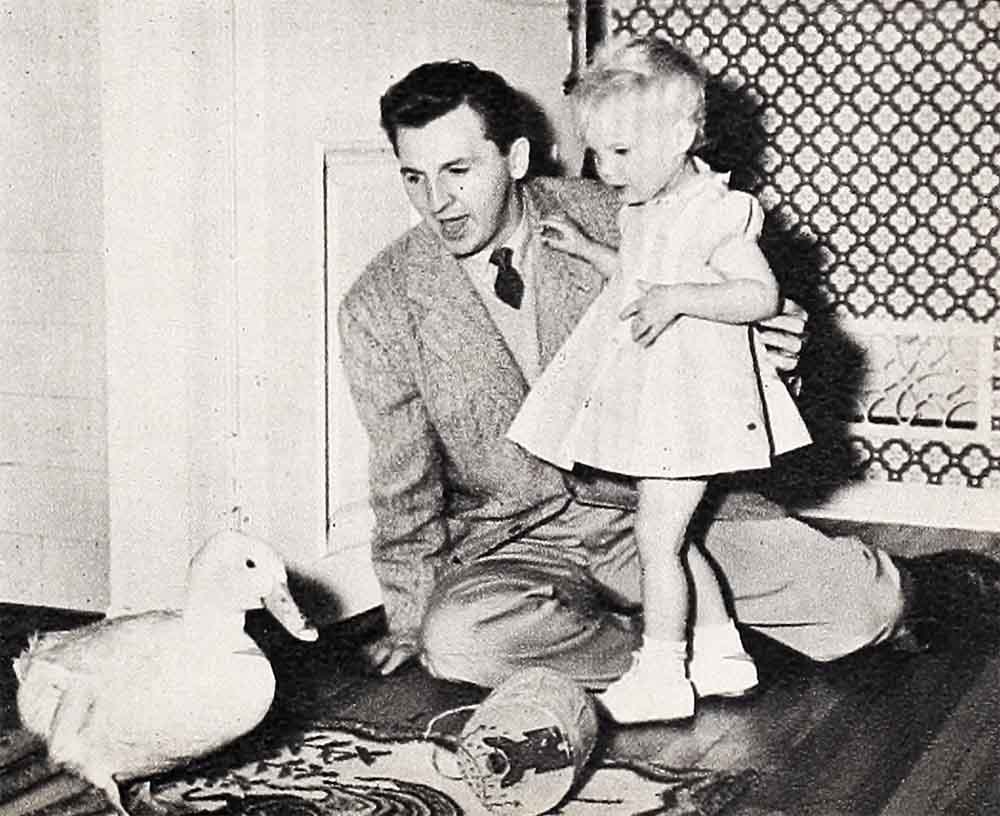

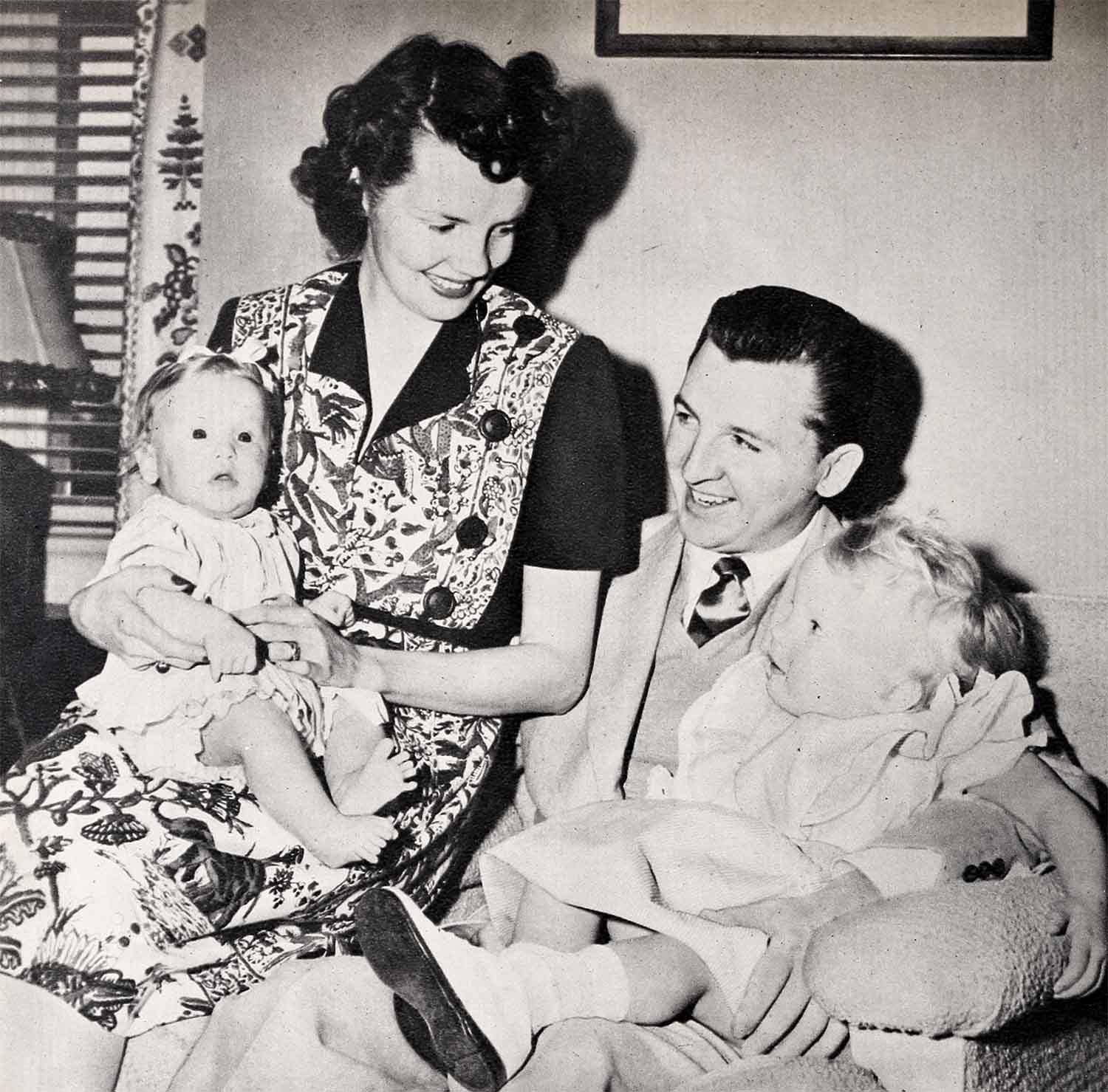

Bracken now is such a success in Hollywood that he can afford to live simply in a small house on two acres in Brentwood, which he calls Nicker-Brack—the Nicker derived from his wife’s maiden name of Nickerson. There he shares a bedroom with his wife, clowns with his kids, two-year-old Judith Ann and six-months-old Caroline Jeanne, makes phonograph records for fun, toys with a large collection of cameras and works on a modern version of “The Pirates Of Penzance.” Four years ago, not being established in filmland, he and his ex-actress spouse felt they should live in a twenty-room house with a pool, badminton court, three servants, thousands of thirsty friends and an overhead running between $1,500 and $2,000 a month. Eddie and Connie did this for a year and don’t regret it; but now they are geared to their little place and a half dozen friends, and they take $25 a week spending money.

Many film fans don’t know that Eddie Bracken was in the movies years ago—as a member of Hal Roach’s famous “Our Gang” cast, which included the immortal Farina and the dog with the black eye. He can’t remember a thing about his “Our Gang” career, except that he is sure he was never very important in the plots.

“I was just cute,” he says. He still is, and is always saying, defensively, “I’m older than I look.” This fools nobody, for he really is younger than he thinks he is, thanks to practically inexhaustible good spirits.

When Eddie got too old to look cute to Hal Roach, somewhere around the age of nine, he came back to New York to make twenty-six pictures with the Kiddie Troupers. After the fourth picture the Kiddie Troupers went broke and this drove Bracken to the stage, where he seemed to specialize in playing child parts in flops.

Bracken, who can’t remember or won’t reveal how many engagement rings he has bought for how many girls, is now devoted to only five people. Number one is his wife, Connie Nickerson, whom he married when both were touring in a George Abbott hit. Numbers two and three are his daughters Judith Ann and Caroline Jeanne. Numbers four and five are Preston Sturges, Hollywood’s favorite genius, and George Abbott, the Broadway comedy producer.

Although Eddie may not be exactly devoted to his employers, Paramount, he is at least docile now after a run-in in which he tried desperately and youthfully to wash himself out of movies. He caused the run-in and now sunnily admits he was wrong. When Buddy De Sylva was production head of the studio, Buddy and business boss Y. Frank Freeman ticketed Bracken for a picture in which he was to play a Frank Sinatra character—a crooner who had given 125 per cent of himself to various agents and managers. They told Eddie that another voice would be dubbed in for his.

Eddie yelped. Hadn’t he sung in some of the best saloons on Queens Boulevard, Queens? Hadn’t he been in the musical, “Too Many girls”? If he was to sing he’d do his own singing—and, anyhow, he didn’t like the whole idea.

Paramount said he’d have to do the picture anyway because it was already in the works and a lot had been spent on it. Bracken said he’d quit movies first—give Paramount everything he had in payment for a busted contract and go back to Broadway. He did, too. He collected every asset he owned—War Bonds, house deed, bank book, jewelry, the works—and dumped them on Freeman’s desk.

De Sylva soothed the seething comedian with a concession: “You can make the picture any way you want, but we must make it. You can do the singing, even. Think it over.”

On the way home to think it over he got an idea. Suppose he did play this Sinatra character—and suppose he got Bing Crosby to dub in the voice? This was a fine, funny notion, and Der Bingle fell for it. The resultant picture is called ‘‘Out Of This World” and Bracken is very fond of it.

Speaking of assets, Eddie’s most useful intangible one is his versatility as a mimic—although he has never done any mimicking for the screen. He likes to take off radio commentators, being very good on H. V. Kaltenborn; his Roosevelt delivery is astonishing and his doing a Betty Hutton was a tour de force.

You remember “The Miracle Of Morgan’s Creek.” Well, in this Miss H. weeps more than Camille and Mimi put together. One day during the filming a sobbing sound track was to be dubbed but Betty wasn’t around. Eddie was, though, and he said, “I’ll do it.” He emitted about seventy-five feet of Hutton-like sobs and they fitted the rest of the sound track perfectly.

Perhaps by way of getting even with Y. Frank Freeman for the Sinatra sweat, Bracken once put Y. Frank in an agony of embarrassment in the presence of no less than Attorney General Biddle. It was this way:

Freeman likes to escort distinguished visitors through the sound stages, and he loves to put actors on a spot. Particularly, he likes to top comedians. Taking Mr. Biddle over the lot one day, he introduced’ Bracken and said, “Eddie, what was it you were saying about the Attorney General just the other day?”

Bracken protested that he hadn’t said anything. “Oh, yes you did,” said Freeman. “Last week you said something about him.”

Eddie, whose mind is lightning swift, figured oh, all right, if he wants to play we’ll play. Assuming the manner and voice of President Roosevelt, he said, “Oh, you mean about Mr. Biddle in the White House.” And in the F. D. R. tones he related a preposterous and hilarious libel about the Attorney General. Everybody howled, including Mr. Biddle—except Y. Frank Freeman. He had met his match.

Another time, when the President was scheduled to make a radio address, Eddie made a nonsensical speech in the President’s voice on his recording machine. Since the talk was an important one and Hollywood likes to keep its brain fixed on things of consequence, De Sylva invited a lot of Paramount talent to his office to listen—Crosby, Hope, Lamour, even Bracken.

The address began all right—and then Bracken’s record was cut in. Eddie still chortles when he thinks of the puzzled looks as they heard the President dribble off into nonsense and even use a shady phrase or two. It took them a long time to catch on.

Bracken is grateful to George Abbott for more than his first breaks on the stage. George taught him to read.

The stage break came when one of Eddie’s many flops turned out to be an important flop—Norman Bel Geddes’s drama about structural steel workers, “Iron Man.” Bracken—listed in the program as Edward V. (for Vincent) Bracken—played a thirty-five-year-old plumber.

Abbott thought this plumber character would be just the man for the role of the school commandant in a road company of “Brother Rat,” so he sent for Eddie. His astonishment was great when a baby-faced boy of sixteen toddled into his office. Abbott forgot about the commandant and signed Bracken for the youngest role in the play, Mistole Bottom. Later Eddie succeeded Frankie Albertson in the main role.

From there on he was an Abbott character. George’s daughter, Judith Ann (for whom the first Bracken babe was named), recalls that the young comedian had 3,000 pictures of himself printed, with his name at the bottom, and would hand them to anybody anywhere like a sandwich man advertising pants to match your coat.

Abbott was interested in his young find but thought his Astorian dialect and limited vocabulary could be improved. He suggested that Eddie read, and broke him in on the Reader’s Digest. Right now Bracken is partial to Joseph Conrad—unabridged.

Judy Abbott, recalling the Bracken of the touring days, says, “Eddie was always getting engaged to somebody. He bought more rings!” One of the girls he bought a ring for was Connie Nickerson, his wife. Connie has given up acting and even turned down an offer from Preston Sturges to play with her husband in “Hail The Conquering Hero” because she thinks one movie star is enough per family.

Bracken, the tireless kidder, can think straight about himself. When Hollywood tapped him he said he didn’t want too much money—and he wasn’t crazy.

“I wanted to grow up in the movies,” he says. “Look at Ezra Stone” (whom Eddie succeeded as Henry Aldrich on the stage). “Ezra went to Hollywood at a terrific salary—and when his option came around they couldn’t afford to take it up. I wanted to start modestly and work up.”

Now he wants to be a writer, director and producer, like Sturges. He will do anything for his mentor, because Sturges put him in the groove of being funny and pathetic at the same time, and Sturges is bringing him up. He explains to Eddie exactly why he does everything he does when he writes and shoots a picture. Lessons like that can’t be bought.

Bracken was born in Astoria and is all Irish. His father worked for the East River Gas Company and used to deliver kerosene in a horse and wagon. The Brackens weren’t exactly poor but they weren’t far from it, and none of the kids got any pampering. Later the father became a gas company executive, but has retired now—but Mrs. Bracken, the mother, won’t quit. She also worked for the gas company and still does, although her son has bought his parents a home and given them all the money they need. Mom won’t stop work because it’s too much fun and gives her a chance to talk about her children.

There are two other sons—John Robert, a Marine, and Joseph L. Jr., an Army sergeant in London.

Along with his dynamite screen companion, Betty Hutton, Eddie is one of the most indefatigable kidders and dashers-around in Hollywood. Between shots on a set he’ll do anything from talking a blue streak to playing tag or wrestling. His humor tends to jokes—good gags or anecdotes rather than practical jokes. He and Sturges, who together know about all the stories there are, endlessly torture William Demarest by killing the point of anything Bill tries to tell.

Bracken doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, hasn’t even smoked for a picture, is quietly religious and is not the slightest bit profane. A friend once summed Eddie up this way: “He would rather want what he has than have what he wants.”

And that’s Bracken in a nutshell.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945