Margaret O’Brien: “I Miss My Mother Most Of All Now”

She was wearing a straight-cut yellow silk Hawaiian dress. Her hair was pulled back into a French knot, but, across her forehead, the uneven black bangs made her face pixie-like. The light California breeze ruffled her hair, and, as she looked up at her fiance, she seemed about sixteen.

“You’d better leave me off at the door of the shop, Bob,” she explained seriously to her fiance. “You know, it’s bad luck for you to see me in my wedding dress until .. .” Her voice became faint; no matter how hard she tried she could never say “our wedding day,” without choking up.

Her fiance, a tall, sandy-haired, good-looking young man, put his arms around her shoulders and, kissing the tip of her nose, he looked down at her reassuringly. “I’ll wait till our wedding day,” he smiled.

“Do you think it will ever come?” she said eagerly. “Ten days. It’ll never come.”

“Anything worthwhile takes time,” he answered her softly, for this was their special secret. “I’ll see you tonight,” he promised.

The bridal shop was empty when she entered, except for a young girl with her mother, sitting on the sofa. I wonder if they can tell I’m going to be a bride, she thought. I wonder if I show it.

Most girls plan their wedding all through their growing-up years. But she had never done this, she thought. It was strange. Except for acting, she had never had another dream. She’d never had time to think about love . . . not until a year ago when she’d started seeing Bob Allen again. He’d never even asked her to marry him—he probably knew it would have scared her to death! They’d just sort of drifted into it. She had been dating three or four boys rather steadily, and then, without a word between Bob and her, she found herself saying no to the other boys, and just going with Bob. He was enough, he was everything.

She heard a door swing open, and the fitter bustled into the showroom, followed by his assistant, whose hands were full of tapes and pins, and a salesgirl holding the wedding dress as if it were a cloud that might blow away.

“Magnifique!” the fitter said.

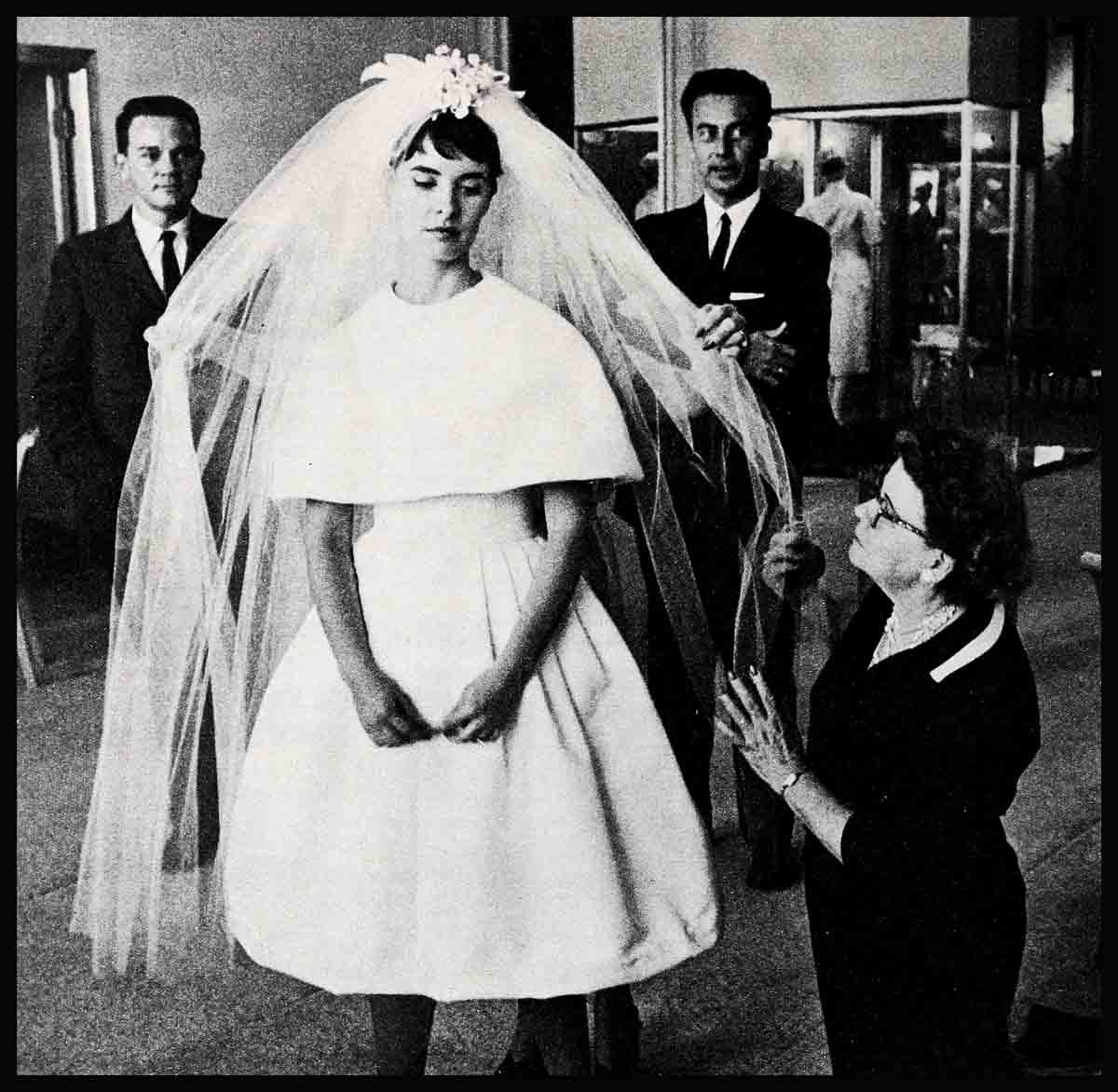

He held up the short full-skirted dress, spreading out its big cape collar. Made of Italian cotton faille, it was a Simonetta, and it was meant to be worn with the high tight gloves that looked like sleeves, and, of course, the tulle veil.

It is truly beautiful, she thought, taking the dress from him and going with the salesgirl to the dressing room. But then, after she had slipped into it and looked into the mirror, she couldn’t help feeling suddenly, unexpectedly, sad. Perhaps it was seeing the other girl with her mother, perhaps it was just a feeling that every girl wants to share this moment with someone close to her. But no matter how hard she tried, she couldn’t help feeling, I wish Mother could have seen me in my dress. I just wish she could have lived long enough to see it.

“It was just made for you!” the fitter said, when she returned to the showroom. “A few minutes and it will be perfect.”

She smiled; she felt that way, too.

“Will the bridesmaids be here this morning also?” he asked.

She shook her head. “No, they’re coming this afternoon,” she told him, thinking how lovely Anna Maria Alberghetti and Bob’s teenage sister, Jean, would look in their champagne-colored gowns. But—she smiled—Maggie, her cousin, would be the proudest one of all. Ten years old and maid of honor! How happy she had been when she’d asked her.

Handing the fitter the very last pin, the woman assistant stepped back. She shook her head admiringly. “What a beautiful bride you will be,” she said. “Oh—and your engagement ring—it goes perfectly with the gown.”

“My fiance designed it,” Margaret said, touching the ring—two pear-shaped diamonds, with baguettes, forming a butterfly on a platinum band.

Margaret smoothed the skirt of her dress as she added, “Oh, and we’re going to Hawaii on our honeymoon.”

“Fine,” the fitter said. Then he looked at the hem of the gown critically. “Ah,” he murmured, “we are done!”

As she stood by the wrapping desk, watching the salesgirl place the gown in tissue paper and then close the box over it, Margaret thought of the hundred-and-one things she still had to do when she got home. wanted to get them done before Bob came tonight.

She raced up the stairs to her apartment and unlocked the door. Then she walked swiftly through the off-white living room she’d designed herself, past the panelled den done in rattan and red, and the green-and-gold papered TV room, to her bedroom. She was glad Bob liked the way she’d decorated the apartment, because this was where they would spend their first year together, while he finished his course at the Art Center. Next year they planned to go to New York, where he’d begin his art career with some advertising agency—and then, maybe, they’d come back west some day, and build a house at the beach. Bob would design the whole thing himself, just as he and his dad had planned their new house. It will all be along simple beautiful lines, she thought. He loves simplicity, he loves beauty . . . Will he love my wedding dress?

Taking it out of the whispering tissue paper, she hung it on the closet door in the bedroom. Oh, it is beautiful, she thought. It’s perfect.

But, once she’d hung it up, she could think of nothing else to do. She’d thought she had to hurry home to handle so many last-minute things, but now they seemed to have evaporated. Everything was sorted and ready to pack. The apartment was in perfect order. It didn’t even need dusting. The only thing wrong was that it was empty.

Turning from the gown, she walked around the bedroom, touching the red-frocked Oriental geisha dolls she’d brought back from Japan when she’d made a picture there, straightening the perfume bottles on the dressing table. Then, with a sigh, she sat down, feeling more alone now than she had that day eight months ago when she was told her mother was dead.

Then, shock had dulled her sense of loss. But now—when everything should be so perfect, when there should be no room for anything but happiness—there was no one to share it with her—here, now.

She felt her eyes begin to fill with tears. I shouldn’t be crying, she thought. That’s not the way it’s supposed to be. But Mother should be here with me. For a full minute, Margaret stared at the large photograph on the wall without really seeing it. Then, holding back her tears, she focused her eyes again, and looked at the little, pigtailed girl she had been, calmly chatting with President Truman. Mother was so nervous that day, she remembered. And so proud. She’d have been proud now, too, Margaret told herself. Mother had liked Bob from the very beginning.

At that time, Bob had been dating Natalie Wood, and she’d been a blind date for his best friend. She hadn’t been able to think of a word to say that whole first evening, she remembered, and had been angry with herself when she got home. But Bob had called her shortly after that, to her surprise.

“I can’t believe anyone’s that quiet,” he told her. “You must have a scintillating personality hidden somewhere, and I want to be the first one to see it!”

In a way, his words had proved prophetic. Although he had gone into the Army and been stationed in Germany for two years shortly after that, he had given her confidence the few times she’d seen him. While he was away they had written to each other—just friendly notes—and then he had come back.

But he had been different. “I don’t understand it,” she had told her mother, as she brushed her hair at the dressing table, “he’s the same, and yet so changed.”

Her mother had set the bedtime glass of milk down on the table and smiled. “I think he’s grown up, Margaret,” she’d said.

“Yes. That’s it. He’s a mar now. He talks about the future, what he’s going to do with his art, things like that. He—do you like him, Mother?” And suddenly she’d blushed.

Sitting down beside her on the dressing- table bench, her mother had pushed back her bangs. “Yes,” she’d said, “I do like him. He’s not like the others. He’s level-headed. He’s a good boy.”

How much she cared for Bob, she was to learn quite suddenly one day. She’d dated him constantly and learned to depend upon his sound judgment, his quiet strength. But it was that day at the beach that told her everything she wanted to know, that told her this would be forever.

It had started out like any other day. A hot sun beat down on the sand, forcing them to race into the water often, to cool off. Standing uncertainly at the breaker line, she’d tried to make up her mind to dive into the next wave and follow Bob. Then, feeling suddenly reckless, joyously reckless, she’d dived. But she had not dived deep enough. The wave caught her in its angry curling motion and tossed her over and over again, finally pushing her up toward the beach. Her arm was scraped and bleeding, and for a moment she lay there choking and exhausted. But the next wave was bearing down upon her, and she tried frantically to jump up and run away from it. Then, just as she realized there would not be time, Bob swooped down upon her. Picking her up as though she were a doll, he carried her to safety.

In a way, it was such a little thing. She had been in no real danger. The wave would have ducked her again, maybe roughed her up some more, but that would have been all. Yet she had been scared.

The sea had looked so huge, so menacing, and Bob, in his act of saving her, had suddenly seemed a giant god, who would let nothing more harm her. He had gotten his first-aid kit from the car and cleaned off her arm, all the time scolding her for taking chances. Looking up into his eyes, seeing the concern—and something more—she knew then that she loved him.

Mother had been so very happy when they’d told her. And now—now she would never see the ceremony. I miss her most of all now, Margaret thought. At times like this a girl needs her mother most. There are things I need to know, things I meant to ask. There was never time enough . . .

Big things—and little things too . . . like how to make beef Stroganoff . . . an elegant-sounding dish that her mother had said was really easy. She wanted to ask Bob’s family to dinner, to show them what a good wife she’d make Bob—and she didn’t know how to cook. She even had trouble with coffee. It always tasted like dish water. For several days before Bob’s folks were to come to dinner, Margaret experimented with the Stroganoff. Once she burned the onions. The next time the sour cream curdled. Finally, the night before the dinner, she thought she had it just right.

The night of the dinner Bob came earlier than his family. “I’ll help with the hors d’oeuvres,” he suggested, looking around.

“The—the hors d’oeuvres?” What hors d’oeuvres? she asked herself, but then she remembered she had a whole box of crackers and some cream cheese. She could top the cheese with olive slices, and that would be all right.

Then Bob’s sister Nita and her husband arrived. They’d double-dated a lot with them, so that would make tonight easier, Margaret thought. “I’ll set the table, so that when Mother and Dad and Jean get here, everything will be ready,” Nita said, and began laying the rose-patterned china and the silver out on the snowy table cloth.

Then the bell rang again. Margaret slid the flank steak she was slicing into slivers back into the refrigerator, pulled off her apron, and went to the door. She smiled at Mr. and Mrs. Allen and at Bob’s teenaged sister, and admitted she was a little nervous.

With Nita’s help the Stroganoff, rice and salad were finally served. But during the meal, Margaret didn’t say more than two words. Then, at last dinner was over. Nita helped her clear the table and stack the plates in the sink. She was humming to herself. How can she hum? Margaret wondered, feeling even closer to tears. She carried the serving dish of Stroganoff over to the disposal and started to empty it.

“What are you doing?” Nita asked, catching her arm.

“Well, it’s awful. I’m throwing it out,” she said.

“But it was fine! You just made too much, that’s all. I think you must have doubled the recipe or something.”

Margaret shook her head. “No, I tasted it. It was awful,” she said. And then the story of how she had lived on Stroganoff for the past few days came out.

Nita burst out laughing. “I don’t blame you for being sick of it,” she said. “After four nights of it I’d hate it, too—but it was new to us and we loved it.”

It was hard to believe. Had it really turned out all right? When Bob and his mother came into the kitchen and seconded the motion, Margaret finally broke down and believed it.

The sun was fading from the room now. Margaret watched the square pattern of light change to a rectangle that grew narrower and narrower. Then the light was gone. Still, she could see the shimmering shape of her gown hanging on the door. Next week, she thought, I will meet Bob at the end of the aisle in that dress.

Filled with happiness and excitement, she stood up and took the dress down, holding it against her. It is beautiful, she thought again. But I wish Mother were here to tell me that. And then she realized something wonderful. Though there had not been time for her mother to teach her to cook, or to advise her on this gown, her mother had given her something infinitely more precious. There had been time for her mother to teach her to wait—and then work—for what she wanted, a “secret” she now shared with Bob. Her mother had, indeed, given her the “secret” of happiness.

Margaret turned on the lamp. Her wedding dress sprang into sharp focus in the mirror, and, behind it on the wall, her mother’s picture smiled. But tears came once again into Margaret’s eyes. Oh, Mother, she said, clutching the dress to her, if only you were here, then everything would be perfect.

THE END

MARGARET WILL SOON BE SEEN WITH SOPHIA LOREN IN PARAMOUNT’S “HELLER WITH A GUN.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1959