Soft-Hearted Menace—Burt Lancaster

Burt Lancaster was so pleased with himself over the present he was giving his wife Norma last Christmas that he couldn’t quite wait for the big day.

He was in that happy pre-Christmas state of mind that even the most devoted of husbands rarely attains. He was positive he knew exactly what his wife wanted.

It was a super-terrific Somali leopard sports coat. Norma already had her minks—the full-length job so expensively brown it was practically black. Then she had the short chic “breath-of-spring” mink scarf. One was for coldish weather; the other, for cocktail parties.

Norma, however, is an essentially practical girl. So she wanted something sturdy yet dashing for those moments when she dropped the four ) kids off at their various schools and she herself went on to lunch or some such, via the station wagon. That’s how Burt hit upon the leopard. It would take a beating, yet complement his wife’s golden-haired, brown-eyed beauty, plus the black dresses she always wears daytimes. The reason for that Burt very well knew: Black’s the only color he likes her in daytimes. White’s all he likes in the evenings.

Thus, Mr. L., after ten years of being passionately in love with the girl, flipped on December 23rd and stood forth with his Christmas offering. But, knowing every shade of his wife’s reactions, he caught the little cloud that passed over her face, to be quickly replaced by a polite smile.

“Why don’t you like it?” he asked, before she could speak.

Norma suddenly began laughing. For your information, Norma is a doll whose sense of humor is always at the ready, but on this particular day there was something like a note of hysteria in her laughter. “Oh, H.B.L.” said Norma, “don’t be angry, but I won’t be able to wear that coat for long. You see, I’ve just discovered that something has happened . . .”

And that was the way that Burt learned he was becoming a father for the fifth time. Which was not according to plan. He learned it on the tide of Norma’s golden laughter, which is the way he’s learned so many other things. Learned it by way of her calling him H.B.L. Learned it with the four “kidlets,” as Norma calls them. They tumbled down the stairs to find out what all the laughter was about and then shouted among themselves, “Mommy’s going to have another baby.”

The newest Lancaster will probably be here by the time you read this. And oddly enough July is the birthday month of three of the others, Jimmy, Susan and Joanna. And there is even the lively possibility that the baby could be doubles, since Mrs. L. is a twin.

Burt himself now rocks with laughter as he tells how, a few nights later, he and Norma, trying to be such very advanced parents, told Jimmy, Billy, Susan and Joanna that they could decide on the new baby’s name among themselves. “It led to the damnedest battle you ever saw,” Burt says, grinning. “In five minutes they were all hitting each other over the head. Each one of them owned the new baby. Each one had the only perfect name for it, whether male or female. Norma and I had to put on quite a show of parental dignity before we calmed things down.”

And that’s the way it is with the Lancasters—the family acts as a unit. And, like many parents before them, Burt and Norma often discover that when they try to be most “advanced” they have to react in the old-fashioned manner. In their attempt to teach the “kidlets,” they discover they, themselves, are the ones being taught.

But to get back to the Lancasters as parents—as you undoubtedly know, they met in Montecatini, Italy, during the war year of 1944. Burt was the tall, handsome, unknown sergeant. And Norma was the pretty stenographer, who, by accident, had been sent to Italy with a USO troupe.

How are some lucky people able to tell at a glance that they are right for one another? What divine sixth sense lets them know they can fulfill each other’s highest ideals? Burt Lancaster and Norma Anderson weren’t one bit alike. He was the rough, tough city boy. She was the pretty little country girl.

His has always been the serious touch. It showed there in wartime Italy when, at their first meeting, he told her that he wanted four children—two boys, two girls.

Hers has always been the light touch. She nicknamed him, then and there, H. B. L. That means, you see, Handsome Burt Lancaster, which she still calls him to this day, particularly in moments of deep emotion.

Yet they were in love, in that instant. You know the stories about Burt being AWOL, trying to follow her, and her being AWOL, trying to get back to him. And it wasn’t just because it was springtime and wartime and they both were hungry for the sight of members of the opposite sex. A hundred thousand other war marriages as hastily performed as theirs cracked up the moment the couple met again, stateside. But Burt’s and Norma’s did not. This marriage was for real. This still is.

Burt came out of uniform, penniless and without prospects. “We’ll eat,” said Norma serenely. “I’m working.”

“This girl of mine,” Burt will tell you now, ten years later, “this girl of mine is like a rock when she makes up her mind to a thing. Nothing shakes her.” Coming back from the war, it must have been both a shock and a delight for Burt to discover his girl was not the frivolous, light-hearted creature that, on the surface, she seems to be to this moment. Incidentally, Burt’s word “girl” is his warmest term of endearment. He’s an absolute mush of sentiment for his daughter Susan. He loves to believe that he’s stern and hard, but all Susie has to do is turn her big eyes his way and he’s down on all fours before her. “Oh, you little girl, you little girl,” he says, whereupon Joanna always cries, “Me, too, me, too, Daddy.”

But that’s getting ahead of this story.

He did actually find himself very quickly after the war, of course. He stood out like a flag in the flop play “The Sound of Hunting,” which didn’t last a week on Broadway but which got him his movie contract with Hal Wallis. He really didn’t want to go to Hollywood. He was quite haughty about movies in those days. In fact, like many a young person without a dime, he was quite haughty about everything.

He needed the money, though, because there was Norma, already putting a family pattern into effect. “No, I won’t go out there with you,” Norma said. “We can’t afford that and you’ll need to keep your mind on your work. Anyhow, goodness knows, I’ll be busy enough producing your first son.”

“How are you so sure he’ll be a son?”

“That’s what you ordered first, H. B. L.”

So, then and there, they decided to name him Jimmy, and the father-to-be sped West, sure he’d be back in New York before the stork. But the Wallis picture intended for his debut wasn’t ready. He sat and fretted and fretted. Then “The Killers” came along. Midway through it, he got that call from Norma. She was in the hospital.

Burt hates flying, but he flew that night. He hurtled into the New York hospital, unshaven and red-eyed from sleeplessness. On his way to his wife’s room, he had to pass the big window behind which the new babies were displayed.

“There was an absolute throng of women around the window,” Burt told me this spring in Mexico. We were sitting together on the set of “Vera Cruz.” There was a throng of extras on the set and movement everywhere. Music was blaring and the lights were up, but Burt was ignoring it because he was reminiscing.

“I saw that crowd and I had only one thought—to push my way through and get to see Norma. But just then I heard one woman cry to another, ‘Oh, look. Over there. That’s the handsomest baby,’ and my curiosity got the better of me. Over those women’s heads I glanced down. And there was my own face looking back at me, only so small and red and with a crown of Norma’s yellow hair all around it. I just stood there and gulped. That was my son. And with that, one of the women turned and saw me, gasping like a fish, I suppose. She gave a yell. ‘Look, it’s the father,’ she said and when I saw all those women turn to look at me, I’m telling you, I just took to my heels and ran.”

But within another hour, his ecstasy was tempered, for he knew then what Norma already knew: Small Jimmy had been born with a club foot.

He had to return to Hollywood at once, of course. He was not important enough for production to be held up for him. But before he left, he’d made his first serious acquaintance with medical science. It would take care and money and time, but his son would emerge as strong as every other boy by the time he got ready to walk.

“The Killers” did it. Burt Lancaster was a star overnight. He rented his first house, at the beach at Malibu, the morning after the preview. He’s always been a man of great social consciousness. But right then he went overboard. He not only phoned Norma to come out at once with the baby. He called his dad, too, and his widowed sister-in-law, and Nicky Cravat, his old carnival partner, and Nicky’s wife and a couple of chums from the Army. They all arrived and moved in. And stayed.

Until the day when Norma told him their second son was impending. “Brute Force” was behind him then and “I Walk Alone” and a couple of other movies—but he didn’t have a dime. He looked at Norma and again he was overjoyed and also worried.

“I guess we’ll have to have a bigger house,” he said.

“Or smaller?” said Norma. “Maybe a lot smaller and not on a beach or accessible, too easily, by car?”

And suddenly they were laughing together, and she was in his arms. “How lucky can a guy be?” Burt asked her.

Bill came into the world a little ahead of schedule, a wonderful golden boy, looking as much like Norma as Jimmy looks like Burt. But two small babies underfoot proved a bit too much for the old Army buddies. They dropped off. And when Susan made her appearance about twenty months later, Nicky Cravat and his wife saw that the Lancasters were definitely crowded. So they took a house, not too far away, from which they could all be old friends without any strain on anybody. Bert’s father, whom they all adore, stuck it out until he heard Joanna was due. “Three I can stand,” Pop said, “but four is an awful lot of babies to be around when you’re an old man. You understand, son?”

Son understood so well he went out and bought Pop a house and a car—and even brought together Pop and an old pal who also was a widower, to share it with him.

And then the real blow fell. Billy, the second son, contracted polio. Jimmy, for whom the Lancasters had felt such concern, was long since brought to full physical vigor. Susibet has always been sturdy as a little tree. Joanna was about to be born—but they forgot everything under the devastating knowledge that Bill might not even live—and if he did he might always be crippled.

Burt and Norma did not sleep that first terrible night. All parents of all such afflicted children must endure the same thing—the first night when you watch the fever curve to see if it is rising or falling, the difference between life and death. Bill’s fever left, but not soon enough. If it does go soon enough, a child can escape. But Bill’s fever persisted too long.

Personally, I think that was the turning point of Burt Lancaster’s life. That night of family travail was the night that transformed him from just another talented and handsome actor into a mature human being. That night set his feet on the path to becoming a great artist.

It humanized him so. Burt’s a great, wonderfully human man, make no mistake about it. I met him first while he was shooting “The Killers,” and I was very pleased the first time he asked me to come and meet Norma, because he had an obsession at that time about keeping “his private life his own.” But at the time of “The Killers” he really was pretty sure that he had the answers to everything—and anybody who disagreed with him was wrong, that was all. One thing he was most positive about was that many people’s attitudes toward social problems weren’t right. Most sincerely, he wanted equal rights for everybody, particularly regardless of race, creed or color. He still wants that, and he definitely practices what he preaches. (He puts it on film too; his current U.A. picture, “Apache,” realistically shows injustices done to the Indians.) But now he knows other people may want to solve these problems, too, yet have a different approach to working them out.

He perceived this that night when Billy’s life hung in the balance. It was his first close-up of the impersonal kindness of doctors. He saw then the impersonal generosity of a big city. He saw how ambulances and nurses and medical science would all swing in together to try to save one small boy. This particular little boy was a movie star’s son, but he could just as well have been a pauper’s son. The care would have been the same.

The Lancasters started their swimming pool the next morning. This, said the doctors, would be therapy for Bill. Burt immediately began making personal appearances for all the medical-fund drives. And week by week, and month by month, Billy got better. The brace that went to his hip was replaced by one that went to his knee, then only to his ankle. And now the good news is that this summer he can have a muscle transplanted that will let him run as easily as other kids.

Which just about brings the Lancaster family story up to date, for nothing has ever happened to those sturdy little girls, Susan and Joanna. They are just the most beautiful, that’s all.

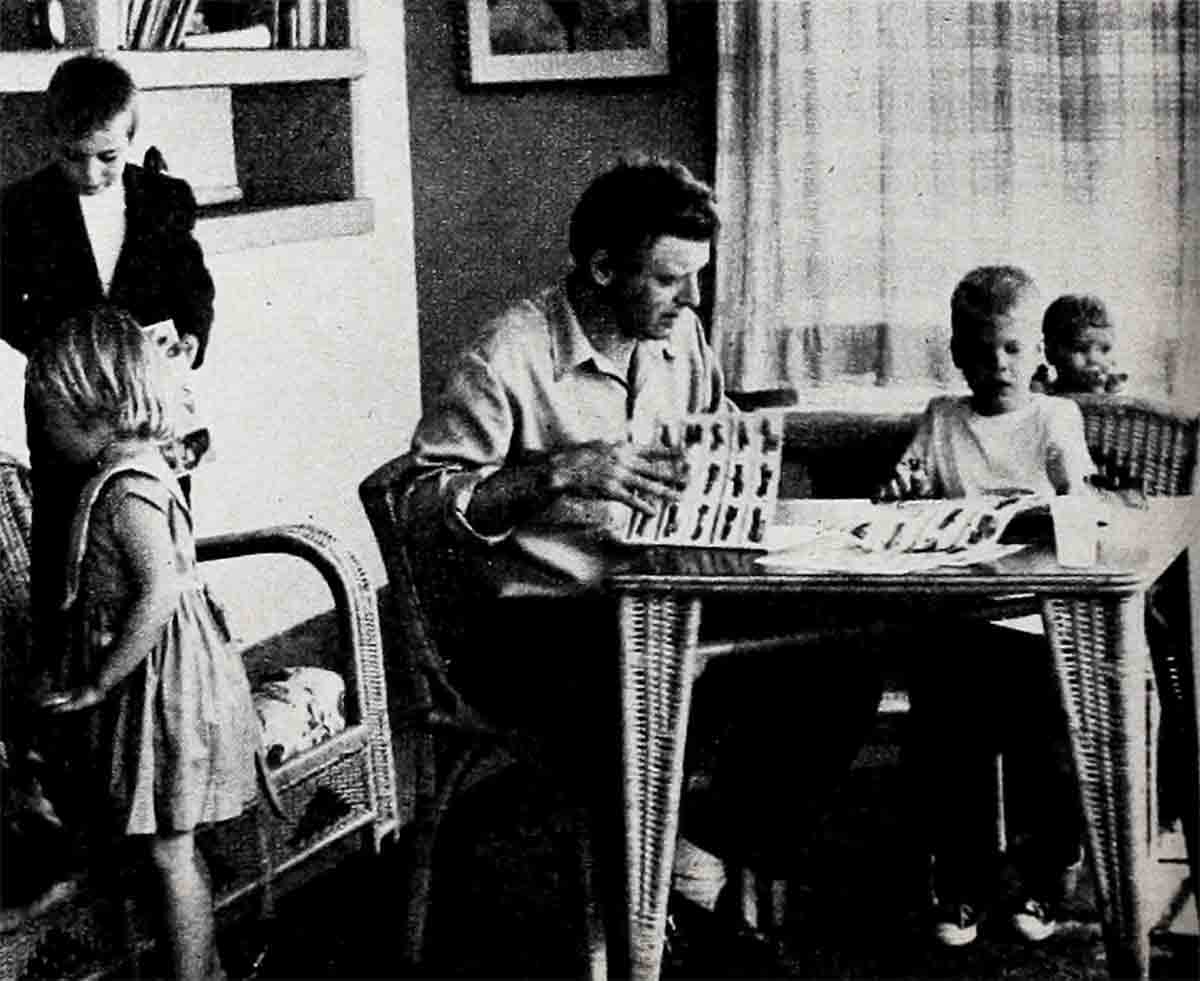

And what will happen when the newest baby comes? Well, there will be moments like this, undoubtedly. Moments like the one last winter when we adults were all playing bridge and Burt went upstairs to find the light burning in Jimmy’s room. There was Jimmy, drawing a mural all around four sides of the room. It ruined the wallpaper, of course, but we all had to stop and go up and see the mural. It really was a wonderful mural, for a boy less than eight.

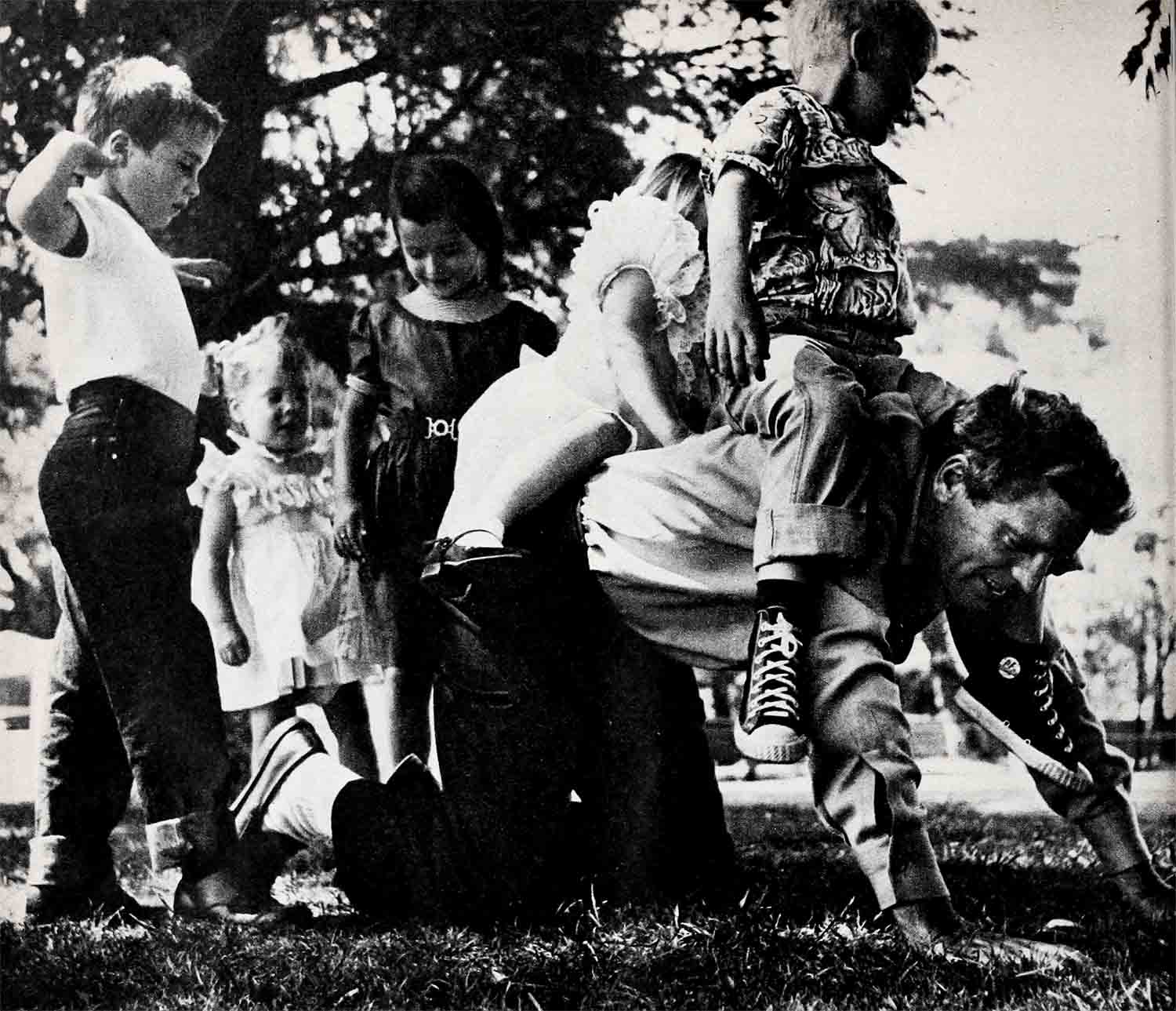

Or moments when Susie and Joanna climb up on their father and push the buttons on his jacket. Sometimes the buttons on the left stand for “down” and the buttons on the right mean “up.” They are never sure. But “up” one of the girls goes high in the air, and “down” the other goes, almost to the floor. But always they’re quite safe in Daddy’s arms. The shower of giggles testifies to this.

“But a fifth,” says Burt and then he smiles. “In my wildest dreams, I never dreamed I could have it so good.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954

No Comments