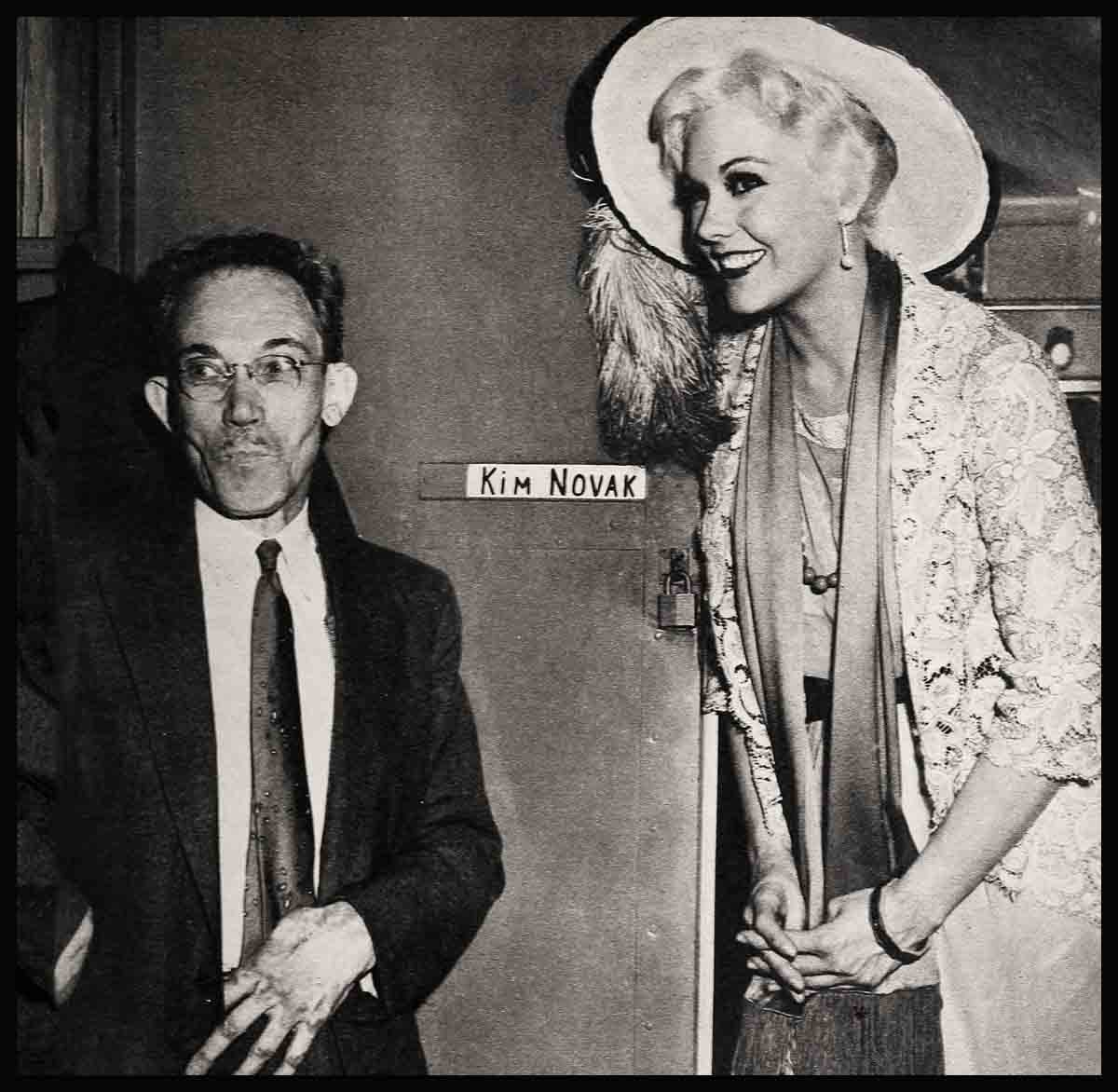

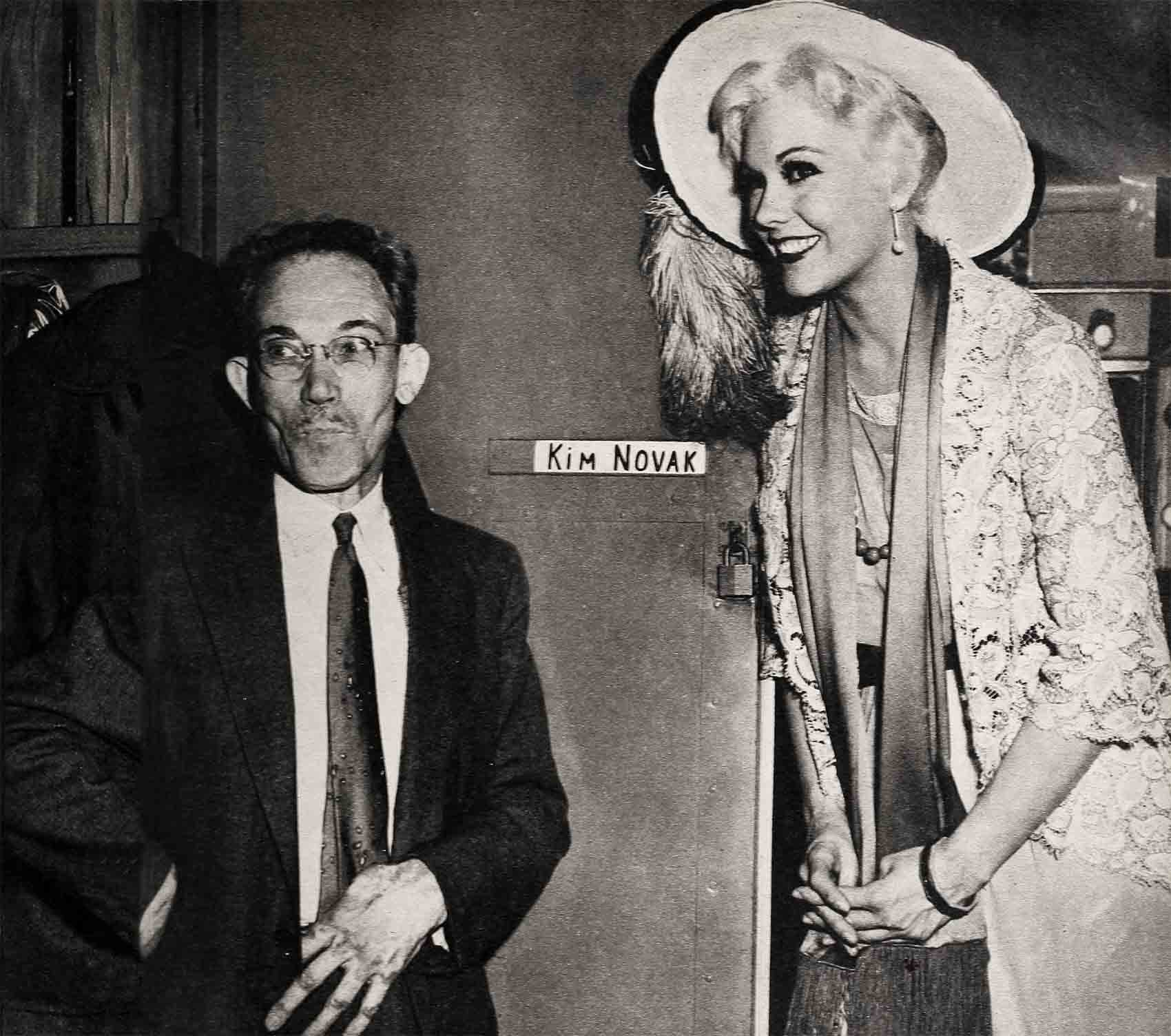

Kim Novak And Her Father

“Kim,” said the man across the desk, “just exactly what is your father?”

Kim Novak stared at him. “What is my father? What do you mean, ‘what father?’ What kind of a question is that?”

The man sighed. “Well, now, Kim, let’s look at it sensibly, from the studio’s point of view. Your father is coming to Hollywood next week, isn’t he? Going to stay a while, visit, see the town.”

“That’s right,” Kim said coldly. “What about it?”

“Ah,” said the man. “That’s just the point. That’s what we have to find out. Now, your mother’s come to see you any number of times. A lovely lady. You took her to premiéres, restaurants, all over the place. Right?”

Still bewildered, Kim nodded slowly.

“And you gave out interviews by the dozen, talking about her. Said she was your inspiration, your guiding light, best mother a girl could have—right?”

“You’re darn right that’s right,” Kim answered. “What about it? It’s all true.”

“Sure it is, Kim,” the man said hastily. “We could see that for ourselves. Sure. But Kim—” he paused impressively. “Kim—when did you ever mention your father in an interview?”

“Why—” Kim said. She opened her mouth, paused, shut it again. A puzzled look came into her eyes. “Why, I—”

“Never,” the man said firmly. “Absolutely never. And your father never came to visit you, did he? Never came along with your mother on one of those trips? Did he?”

“Well, no,” Kim said. “But what—”

The man nodded. “Now. Kim, I’m not prying into your business for fun, you know. But the studio pays me a good salary, and I’m supposed to protect their property in return for all that money. You classify as pretty valuable property, and I’m going to look out for your best interests, see? Now, you take your father. How do we know what he is? All this time you’ve been hiding him, and now just when you’re going into the biggest picture of your career, you spring him on us. Well—” He looked at Kim. “There was the famous case of another blonde in this town,” he said, “who never talked about her mother. Just never mentioned her much, never produced her—nothing. So this blonde becomes a star—a big star. And then what happens? Turns out her mother, whom everyone had figured was dead and buried, has been in and out of looneybins all the time—”

“Stop it!” Kim cried. Of course she knew who he was talking about—Marilyn Monroe. But how cruel to say it like that. How cruel to say it at all. How unfair. “Don’t you ever talk to me like that again,” she ordered furiously. “And—and don’t talk to me about my father, either. He’s perfectly wonderful—and—and even if he were awful, it’s none of your business!” She stood up swiftly, tossed a white stole over her shoulders. “I’m leaving now,” she said.

Publicity got her to the top—fast

The man stood up behind his desk. towering over Kim. “Now look,” he said. “You’ve come up fast, Miss Novak. You’ve got looks and you’ve got talent. But looks and talent didn’t do it all for you. You’ve had publicity—miles of it. That’s what got you to the top so fast. And that’s what can drop you off the top just as fast. Remember that.” His gaze softened. “Look. I know you like being a star. You gave up getting married a couple of years ago, just to give your career a break. A girl can’t do much more than that. You’ve worked like a dog ever since—I know. And now you’ve got it made—almost. Everything up till now was to make you famous. But theJeanne Eagles picture is more than that. It’s Oscar stuff. And it’s more box-office than you ever had before.” He looked at Kim and saw that she was silent. watching him.

“Therefore—” she said.

“Therefore, don’t take any chances. Maybe your father is fine. I’m not saying he isn’t. All I’m saying is—what do we know about him? Is he liable to pull a boner?

“Is he liable to say the wrong thing to the wrong reporter?

“How are his manners in a night club?

“How’s his English?

“What does he look like? For that matter, how much do you know about your father? All I’m saying, Sweetie, is this: if there’s the smallest chance in the world that your father could queer things for you now—don’t let him come.”

Kim stood still for another moment, looking at him from the doorway. Finally her lips parted. “Good-by,” she said distinctly, coldly. She walked out, her shoulders back, her head high—the picture of defiance.

But outside the office, her steps slowed. What did she know about her father?

Her mom—so strong

She went home. She walked up and down in her living room until she thought her head would burst. Then she changed clothes quickly, climbing into slacks and a loose sweat shirt, and went outside to find her bike. And five minutes later she was doing what she always did when she was troubled or unhappy or just needed to be alone and at peace—she was peddling away from the city, out along quiet roads and some grassy slope with a quiet green view—a place to park the bike and stretch out, chew a blade of grass—and think. . . .

It was true. Her mother was mostly— by a big margin!—what she remembered of childhood. She had been such a strong-willed person, her mother—in fact, she still was. Always insisting that Kim get married, raise a family; always turning her life upside-down for inspection and correction on her wonderful, hectic, maddening visits to Hollywood. But her father . . .

She remembered him as he was in her childhood. Even then, to her upturned face, he seemed a small man in size. Especially small near her big-boned, hearty, laughing mother. And quiet. Her mother’s voice echoed all over the house, calling people, giving orders, making things go—and her father—where was he?

Suddenly a voice came back to her, through the years: “Sssh, Marilyn—your father’s writing poetry upstairs!”

She hadn’t thought of that in years. Of course! It was her father who had first told her what a rhyme was, who had been so delighted when she brought him a poem she wrote in school. Lying in the grass, Kim Novak laughed delightedly. So that was where she got her passion for scribbling poetry—those poems she never showed anybody. It was a good memory to have found.

Something about her hands

Then she stopped laughing. Another was nudging at her mind. Something not happy—not happy at all. What was it? Something about her hands. Something—oh, yes—

It had been that same day. Her father had pencilled in corrections on the poem while Kim hovered, thrilled and proud, at his elbow, helping him. Then he had handed her the pencil and a clean sheet of paper. “Now,” he said, “you write out a clean copy so we can show Mommy.”

Joyfully, she reached for the pencil, began to print in careful neat letters. Then suddenly, “Stop!” her father said. “Why are you writing like that?”

Kim looked down. “Like what, Daddy?”

“The pencil—you’re holding it in your left hand. It belongs in your right. Like this.” He transferred it firmly.

Kim blinked. She had learned to write left-handed. The teacher had only fussed the first day and then let her write with her left hand. She told her father so.

“No,” he said. “No, that isn’t good. Try it with your right hand. Come on, now. You can do it.”

She clutched the pencil. Daddy wanted her to. Sweat stood out under her blonde bangs. The pencil moved awkwardly. Letters sprawled across the page. “I can’t,” she whimpered.

“Of course you can.” Her father’s voice was worried. “Try again.”

She tried. He went from worry to mild annoyance, almost to anger. It wasn’t right to write with the left hand. She ought to do it properly. She could if she tried hard enough. She wasn’t trying. . . .

The poem was forgotten. The pleasure and pride drained out of her.

Suddenly Kim remembered ‘Mickey’

Now Kim sat up, staring across the cloud-studded sky. Was that why she hadn’t mentioned her father much—the little nagging feeling of shame that came to her when she thought of him, because she had disappointed him? No matter how hard she tried, she hadn’t been able to live up to what he wanted from her. She could hear his voice again: “Try, Mickey. Try.”

And suddenly she thought: Mickey! He always called me Mickey—except when he called me Mac. Because he wanted me to be a boy—he wanted a son so badly. Is that how I disappointed him too?

Remembering, so many things came back.. Her father striding into her room with a crayoned sign in his hands: “Mickey, did you put this in the window?”

She looked at it; it read: BRING SICK PETS HERE. “Yes,” she said. “I thought I’d kind of start to practice taking care of sick animals now so Il be even better after I study how to, you know. . . .”

Her father sighed. Look, I won’t stop you if you want to do that. It’s very—nice of you. But Mickey, there are so many more important things going on in the world. See?”

He spread out a newspaper before her “Look—look what they’re doing in England now. And—and the Middle East. Do you realize what all this means—to us, to our future?”

She stared at him blankly. “No.”

“But you should. It’s vital. You’re going to be a voter some day, aren’t you? Now I’ll tell you what: you give up this running around the neighborhood every day taking care of every hurt alley cat you find. Then you can do your homework in the afternoon instead of leaving it till after dinner. And you and I will go over the newspapers together in the evenings. OK?”

“But, Daddy,” she said, “I—want to—to—you know—take care of animals and things. I mean, my goodness, England can take care of itself without me. I mean—I just don’t care about that sort of thing . . .”

She couldn’t be the son he wanted

Now she winced, remembering the hurt in her father’s eyes, the silence with which he folded up his paper and left her room. She had been too young then to feel it, but now—suddenly she wanted to make up for it, to be what he had wanted.

“But I couldn’t be your son, Daddy,” she whispered aloud.

Had she wanted to maybe, as a youngster, without realizing it? Was that what had kept her from realizing her own beauty so long, had kept her in jeans and t-shirts long after the other girls were in Sweaters and skirts. Maybe . . . maybe . . .

But after all, she was a success now wasn’t she? Maybe she didn’t read all the papers every day, but she was Somebody she was Kim Novak the movie star—surely he was proud of her now. She thought back, trying to remember her last visit home to Chicago. When was it—Christmas time?

She had been trimming the Christmas tree when the call came. Her mother had hurried in from the hall: “Kim, it’s the studio in Hollywood. Hurry up—long distance. . . .”

She climbed down the ladder and ran to the phone. She thought maybe they had a new part for her. But it wasn’t a part—it was a whole new contract—it was too fabulous to believe. Five minutes later she put down the phone and turned a glowing face to her family. “I can’t tell you all the details,” she said breathlessly, “but what it amounts to is this”—she caught her breath and whirled away, pirouetting joyously across the floor—“they’re giving me all the parts they’d have given Rita Hayworth! I’m going to be their biggest star!”

Why couldn’t he rejoice?

Her mother went into ecstacies, of course—laughed, cried, grabbed Kim and kissed her, ran to call the relatives—but suddenly Kim had subsided, had come to a halt before her father, who stood silently to one side. “Well?” she demanded. “Well?” And knew that she was really asking: are you proud of me now?

And her father had said crisply, “It’s all right, I guess—but it takes a lifetime to make a great actress!”

Remembering, Kim got mad all over again. Was that what he should have said right then? Couldn’t he ever forget he once taught school and stop moralizing? Why couldn’t he rejoice with her, be happy for her, not take the edge off everything? After all, who was he—just a railroad freight dispatcher, that was all. Who would ever have heard of him if it weren’t for her? Who bought his wife a mink stole—not him, but his daughter, that’s who. Why she’d even had to help out with her baby sitting money and her modelling fees when she was a teenager—and now she was wearing cashmere “and furs and silks—and he was still going to work in overalls.

“My Lord,” she thought suddenly. “What if he’s right—that man who said not to let him come? What if—what if Daddy doesn’t like the Jeanne Eagels movie—he’d be just the one to say so right out to the director or heaven knows who. What if he thinks my costumes are indecent? What if he bawls me out right in front of everyone? What if it gets in the papers? What if—”

She stood up swiftly, brushed herself off and clambered back down the hill to her bike. She turned it and headed back for Hollywood, her thoughts racing ahead of her. Maybe—maybe it would be better if Daddy didn’t come—right now. Maybe she should write—no, call—and suggest that he wait a while—just till Jeanne Eagels was all wrapped up. Because it wasn’t as if this was just any picture. This was really the start of her career, in a way, her biggest chance to prove she was an actress, not just a blonde with a pretty face and a good figure. After all, she couldn’t coast along on that—she had to keep going—it took work and living and years of effort to make a great actress—

The bike wobbled suddenly and came to a halt. Kim put one foot down to brace herself. That was just what her father had said. Just exactly what he said!

The best possible daughter

A passerby would have thought the girl on the bike had frozen there, so still she stood, her face grave. thinking as she had never thought before. For Kim was feeling the anger draining out of her. leaving behind a vast, sudden understanding. Why, he’s right, she was thinking. Of course he was right. Haven’t I always been furious when people took second-best from me and then told me I was great? Haven’t I always yelled that they should make me work harder—because there’s better than second-best in me—if they can just dig it out? Well, thats what Daddy was saying, too. That’s what he’s always been saying, all my life. Not wanting me to be a son—just wanting me to be the best possible daughter. Sure he wants a lot from me—a lot better than just fame and praise. But he doesn’t demand any more than I demand of myself. Than I mean to get!

She stood there in the road, and she began to laugh. Why hadn’t she ever seen it before? For all her strength, her mother would have let her coast along and never thought anything of it. But her father—her quiet little father—he was the one in the background, who made her want to go on and on and do things better and better!

All right, Kim thought. Come ahead, Daddy. I don’t care what you do or say, or what anyone thinks of you. If you want to bawl me out for something, go right ahead—you’re my father, and you’ve got the right. If you want to talk back to directors and producers, you can go right ahead—because maybe you know more than they do after all. If anyone wants to look down their noses because you work for a railroad—well, let them look at me that way too, and welcome— because the best thing I ever was or will be is the daughter of a freight dispatcher named Joseph Albert Novak—the guy who always wants to be proud of me—for the right reasons! Come ahead, Daddy—I cant wait.

A deep breath—and then . . .

A week later, Kim Novak stood on the platform at the railroad station, waiting for her father’s train. She had no inkling of what was to come. She didn’t know that in the weeks ahead, at parties and premiéres and dinners, her father would charm her friends, make columnists beam. She didn’t know that the pride and happiness in his dark eyes would be shown in a hundred news photographs to be seen and noted by millions of her fans. She didn’t know that when he visited her on the set of Jeanne Eagels, the director, hurrying by, would stop to say—“Pardon me—but Miss Novak, your father is exactly the type we need for that bit in the fourth scene—do you think he would do it for us? Would he be offended if I asked?” She didn’t know that her father would do the scene to the applause of the cast and crew and walk off the set to hear someone whisper. “Now I know where Kim geis her talent—it’s pretty obvious!”

No, she knew none of that. All she knew as the train pulled in and her searching eyes found the dignified little man descending the steps was that her father had come to see her in Hollywood. All she knew as she ran into his arms was that she was proud of him and loved him—and would want, all her life, to have his pride and his love in return.

Kim Novak took her father’s arm. She walked with him down the long platform to the other end. where a group of Hollywood dignitaries stood, also meeting friends on the train. She stopped before them, and looked around the group—some of the biggest names, the most important men and women in Hollywood stood there. Kim Novak took a deep breath. Her hand tightened firmly on her father’s and pleasure were in her voice.

“I’d like you,” Kim said, “to meet my father . . .”

THE END

—BY SUSAN WENDER

Kim will soon be seen in Columbia’s Jeanne Eagels and Pal Joey.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957