Tough Softie—Victor Mature

Recently Dorothy Mature filed suit for divorce. After a lengthy absence from the headlines, Victor Mature was again making the front page. This time he wasn’t trying. He had hoped that the matter could be settled quietly behind the closed doors of their lawyers’ offices. He refused to make a statement to the press. Dorothy was equally firm in refusing to discuss what finally broke their six-year marriage.

Talk said, “It’s all his fault.”

“Her fault,” corrected the other side.

The party who came closest to the truth said, “There are two sides to every story. I guess there have always been two sides to Victor’s story.”

Victor’s reticence to speak of the divorce—or very much these days—is quite unlike the Mature of the old days. Only a few years ago his voluntary withdrawal from the limelight would have been considered impossible. He was the man with the knack for making the front pages. In doing so, he became one of the most controversial figures in Hollywood. He still is.

Vic is a man who is many things to many people. He’s been called a publicity hound. He’s been called a recluse. He’s been dubbed one of the most complex individuals in film-land. Yet his philosophy of life is a simple one.

Financially speaking, it’s been said that he can make a Scotsman resemble a spendthrift. “Sure he’s tight with a dollar,” says a friend. “But he’s loose with a hundred dollars.”

He can make a mistake like any other member of the human race, but he’s no slouch when it comes to facing up to them. Although it’s been said that he’s hard to know, there’s a whole league who know him well and disagree. One thing is certain. There is no happy medium of opinion on Victor Mature. Just as there is no happy medium when it comes to loving him and being loved by him. “It’s a little frightening and exciting all at once to find yourself in love with a man like Victor,” said Dorothy Stanford just after their marriage. “It’s a little like having a benign whirlwind hit you and settle down to stay. He isn’t just the kind of person you can meet—say on a vacation—have a summer romance with, and put out of your mind and life when summer’s over. Once you love someone like Vic, he fills up your whole world—your thoughts, your heart, your life.”

It’s true. With Victor, it’s all or nothing at all. And he’s had both. There just is no middle ground. As long as he’s alive, he’s going to get the most out of living. The mediocrity, for which some settle, is not enough.

In friendship, he expects and receives unswerving loyalty. He also gives it, twice over. If a friend needs a shoulder to lean on, Victor arrives with two broad ones. If a friend needs a dollar, Victor is there with a checkbook. If he needs a home, Victor’s door is always open.

Once, during a housing shortage, he converted his garage into an apartment for an ex-Coast Guard buddy and his wife. Los Angeles housing authorities ruled that, because of zoning laws, this was illegal. The matter was settled, but not before Victor had threatened to call out the American Legion and march on City Hall. And the veteran and his wife stayed on in the apartment until they found other living quarters. “He’s done things for people that few know about,” says one friend. “He’s helped a lot of folks financially and has never given a thought to repayment. For years, he’s been sending children to summer camp with Mike, his son . . . kids that might not be able to go otherwise. Reward? All he has to do is look at those happy faces. And they light up whenever you mention Vic’s name!”

He’s been called dour, sour, glum, and his moody features lend credence to the rumor. True, he has been known to keep a straight face. For instance, there was the time he applied for membership in an exclusive Los Angeles country club. “We’re terribly sorry,” the manager told him. “But we don’t permit actors to become members.”

“Look,” said Mature, “I can show you my last twenty pictures and prove I’m no actor.”

Today, he is an actor. The critics at- test to the fact and the fans agree. And, according to the Hollywood boxoffice theory, there are no other catagories left in this world. Seemingly Mature is casual about the movie business. He’ll look over a script to get the gist of it. He’ll take it along with him to the nearest golf course, hand it to a friend and ask, “Read it to me, will you?” Then he tucks the script away in his golf bag and trots out to break 80.

Yet, on a set, he gives his role concentration and respect. When he was shooting “The Robe,” the day arrived for the crucifixion scene. One member of the company began making with unnecessary jokes before the filming began. Victor stopped him in no uncertain terms.

If you saw that scene, it’s likely that you’ve never forgotten, or ever will, Victor’s expression as he watched, and his final gesture of letting his head drop to his chest. You knew what it meant to Demetrius and to all of the others. You were there. “How did you do it?” someone asked him later. “What were you thinking about? Your eyes told the story so well, how?”

“I tried to make the Sign of the Cross with my eyes,” Victor explained quietly. It was his own idea and decision.

Upon occasions, he has gone into pictures that he knew would make the critics shudder. Each picture has made money. Each role has added to the credit side of his experience ledger. Despite his star status, he isn’t above taking a third lead. “I don’t care, if I think the role is a good one,” he says. “It’s the part that counts.”

Those who work with him at MCA, his agency, find him most agreeable when it comes to cooperation—and sometimes difficult when it comes to being located. The MCA office never sees him. He calls in to report his whereabouts. “Is this the office of George Chasen, the greatest agent in the world, who’s with the greatest agency in the world, and who has the greatest secretary in the world?” he’ll ask by way of greeting.

Needless to say, the agent, the agency, the secretary believe that Mature can do no wrong. He is, in their estimation, the greatest. Even when, every-so-often, they have to manage to locate him by guesswork. Recently, via phone, he was asked the address of his newly acquired home. “Honey,” said Mature, “I don’t know the house number, but the place overlooks the ninth hole of the golf course down here—if that’s any help!”

He hates to be alone. He loves people and loves nothing better than to be surrounded by his friends. With a new house at his disposal, Vic packed up and walked out—moving in for a time with Mr. and Mrs. Barger who live nearby in Rancho Santa Fé. After that, he was the guest of Mr. and Mrs. Beldon Ratleman at El Rancho Vegas.

“You have to work to make friends,” says Victor. And he does. And greater mutual loyalty cannot be found anywhere. If a friend of his friend happens to make a belittling remark behind their buddy’s back, Victor speaks up. “Tell you what let’s do,” he’ll suggest politely. “Let’s go over and see him together and you can say that again, to his face.”

He makes a great point of studying people. He can spot a phony soon after he meets one. He’s rarely rude. Once he met two phonies. He and a friend sat and talked with them for a time. After a while, Victor suggested that they leave. “Let’s go down to La Jolla for a while,” he said.

The friend agreed. The rest of the party thought it would be a fine idea and invited themselves along. “We’ll meet you there,” offered Victor.

They climbed into separate cars and drove away. When they reached the crossroads, Victor stopped. “Which way is La Jolla?” he asked.

“South,” said his friend.

“We’ll go north,” said Victor.

He also attempts to avoid rules which he knows are phony. He’ll abide by them if he thinks they’re reasonable, or if someone asks him to in the right way. If not, he’ll find a way to break them—perhaps only a fraction, but enough for a good laugh. At one of his clubs there is a rule which states that all golfers are required to wear a shirt while playing, even when the temperature reaches the hundreds. One warm day Victor removed his shirt. The golf pro asked that he put it back on. “Sure,” said Victor.

After complying with the request, he took out his pocketknife and cut the legs out of his slacks. “I’ve got my shirt on. Okay?” asked Victor.

“Okay,” grinned the pro.

Most of his life, he’s made his own rules, within reason. And life has never been dull, for Victor Mature or for those around him. For instance, at the age of four, he decided to take up smoking, reached for his father’s pipe and proceeded to light it. The flame was a mighty one and the tobacco caught fire. However, for a while, no one seemed to notice the threat to his growth, tobacco-wise. The curtains were also burning.

He was a high-spirited boy. By the time he was fifteen, he’d been thrown out of a number of schools that weren’t up to coping with him. At one school, his mother was called in so many times, other students began to believe that she was working there.

He’s still an extrovert. But there are those who say that he’s an extremely sensitive one. He’s also a businessman, and a shrewd one. This, too, dates back to his childhood. At the age of nine, he was selling magazines. Later, he went into the candy business, his job being to persuade the stores to sell the sweets. “Just let me leave them with you,” he’d say persuasively. “If you can’t sell them, I’ll take them back.” They always managed to sell the supply.

He set up candy counters in the fraternity houses at the University of Kentucky and in the sorority houses at the University of Louisville. Beside the candy, he placed a box. Payment was on the honor system.

For a time, he ran a hotel elevator. However, he was asked to leave one day when he hustled the manager out of the contraption and slammed the door behind him. His co-workers at the hotel in those days are still his friends, and he sees them whenever he goes home to Louisville.

After completing school, he took over a restaurant in his home town. He’d worked for his father in the cutlery business and had saved enough for a down payment. He lost money the first month, knowing little about the new venture. However, he knew enough to hire an expert to run it for him after his initial failure. When Victor sold the restaurant, he came out of the deal with more than a reasonable profit.

Many have tried to explain the Mature of today. What gives a man such drive? What makes him go up the ladder of success with an unequaled sense of urgency? What goads him on? Perhaps, in Victor’s case, it was an inheritance from his parents.

His father was Austrian-Italian. His mother, French-Greek-German-Swiss. They came to America from Innsbruck, Austria, and eventually settled in Louisville, Kentucky. They loved their new country and they wanted to grow with it. Victor’s father began his life in America as a knife sharpener. He was an astute man with great foresight and warmth. Victor’s father built up a prosperous cutlery and refrigeration business. He was a self-made man. He wanted the same for his son. His son wanted it, too.

Victor vowed that someday he would be Somebody, a down-to-earth somebody. And he made good his word. Almost invariably stars change with their success. It’s part of the routine, one that Mature has never followed.

But how could he best achieve the success he sought? There was Hollywood, well-advertised as the land of opportunity. With forty-one dollars in his pocket and a supply of canned goods in his car, Victor departed for California. When he arrived he wired his father, “ARRIVED IN CALIFORNIA WITH ELEVEN CENTS IN MY POCKET. LOVE AND KISSES, VICTOR.”

There was, he figured, a faint chance for a money order to come his way. Instead, he received a wire. “I ARRIVED IN NEW YORK WITH FIVE CENTS AND COULD NOT SPEAK A WORD OF ENGLISH. YOU CAN SPEAK ENGLISH AND HAVE SIX CENTS MORE THAN I HAD. LOVE AND KISSES, DAD.”

“I didn’t know exactly what to do when I got here,” remembers Victor. “But I began to think that my most promising future would be as an actor.”

He went straight to Pasadena to attend tryouts at the Pasadena Playhouse. There, he read for the Playhouse executives and an audience full of other aspiring young actors and actresses. Later, Gilmore Brown, head of the Playhouse, summoned Victor to his office. He’d liked the young man’s reading. Was he aware of the fact that members of the Playhouse group worked without salary?

He wasn’t.

“I’llsee what I can find for you,” Brown told him.

A few days later, the theatre man called, and Victor returned to his office. There were odd jobs to be done: answering the phone, cutting the grass, running errands. The pay was fifty cents a day.

“If you’re on a budget like that one, there’s nothing like living in a tent,” says Victor today. And he did. For three years, he studied at the Playhouse. His home was a tent. Later, the magazines made sort of a joke of it. But it wasn’t a joke at the time.

In 1938, he married Frances Evans. She was an actress at the Playhouse. Frances wanted a career. Victor wanted a career. Somewhere along the line, love got lost. They were divorced in 1939.

During the yearly six-weeks vacation allowed by the Playhouse, Victor worked for extra cash. He washed dishes, cleaned wallpaper, Simonized cars. When the theatre sessions began again, he went back to his other chores. In all, he appeared in well over sixty plays at the Pasadena Playhouse.

Then, Hal Roach began his search for a cave man for “One Million B. C.” He saw Victor’s picture on a folder.

A few days later, Roach himself sent for Victor. He met the charming girl who worked as a casting director. “He wore a pair of slacks and a sweat shirt. They were about all he had,” she remembered years later. “He’d come in and just grin. He had a certain way with him. A definite appeal that left you with a very positive impression of his personality, a quality that a screen personality must possess.”

Victor was tested and given a role in “The Housekeeper’s Daughter.” However, he remained in his tent. “I couldn’t afford an apartment,” he says now. “Well, perhaps I could have, but I’d have had to sign a year’s lease and I wasn’t sure what was going to happen.”

He did move his tent into a Hollywood backyard in order to be nearer the studio. And he made improvements. The tent acquired a floor and a stove. It also had books and pictures and several pieces of furniture. “It seemed strange to have money in my pockets,” says Victor. “I’d been without it for such a long time. And I swore I’d save it, so I’d never be without it again.”

After “The Housekeeper’s Daughter” came “One Million B.C.” and a few others. And with the series of parts came more income and a more carefree life.

Victor liked being seen with small blonds. A waiter at one club vowed that in three months he had seen Victor on the dance floor eighty times. And had counted eighty small blonds. And, of course, a photographer or four were always close at hand.

There was Betty Grable. He flew to New York to be nearby while she was appearing in “Dubarry Was a Lady.” While he was there, Moss Hart offered him a role in “Lady in the Dark.” Mature accepted and became one of the more successful rages of Broadway.

And he fell in love. The girl was Martha Kemp, widow of the bandleader Hal Kemp. After a hectic courtship, they scheduled the wedding.

The marriage didn’t last. It’s said that Martha didn’t like Hollywood, that she was indifferent to the industry which was Victor’s life.

When World War II began, enlisted.

Like millions of other servicemen, Victor left a girl at home, Rita Hayworth. They’d met while working together in “My Gal Sal.” At the time she was divorcing Ed Judson, and she was a very unhappy girl. At first, with Victor, it was a matter of cheering up his co-star. He’d play jokes, keep her laughing. She needed laughter in those days. And from the laughter came love.

Then he went away to war. He spent three years in the North Atlantic and the South Pacific as Bo’s’n’s Mate. The “gorgeous hunk of man” was affectionately dubbed “hunk of junk,” and he liked it that way. “And do you know what he did?” asked one of his Coast Guard buddies. “He turned down two chances to wear gold braid. Said he didn’t want a commission, that he’s allergic to being called Mister!”

Once, on leave, he visited Hollywood. A premiere was being held across the street from his hotel. Victor refused to attend. “I’ll watch from here,” he said, declining the invitation. “They’re taking pictures over there, and by the time they reach the magazines, I’ll be back at sea. Then what? People will look at the pictures and think that that lousy Mature is having himself a great old time in Hollywood while everyone else is out fighting a war.”

The war changed Victor Mature. He returned to Hollywood with a new set of values. Publicity had been necessary to call his name to the attention of the public. But a man should be accepted for his ability. He had to stand on that ability.

The broken romance with Rita had also sobered him. While he was away, she had met Orson Welles. They’d done a magic act together for benefits. Orson was the magician, Rita the girl he sawed in half. Victor first heard of their marriage when his ship docked in Boston. The news was shouted to him as he came down the gangplank. He stopped for a moment. Then he grinned a wry grin. “Well,” he said. “I guess the way to a woman’s heart is to saw her in half.”

Victor first met Dorothy Stanford one day at Laguna. Dorothy and Mike, her young son by another marriage. Mike and Vic became buddies immediately. And the mutual friend who had introduced the trio sat around beaming. All three continued to become fast friends.

A little over a year later, Dorothy and Victor were married in Yuma, Arizona. Yet it was a case of opposites attracting. They liked different types of people, different kinds of amusements. In the end, it became a case of incompatability that couldn’t be worked out. But not because they didn’t try.

They settled down for a while in Victor’s pre-war bungalow. He was proud of the small house. It was the first piece of property he’d ever owned and to him it represented a milestone in his life. When the city proposed building a freeway through his living room, he threatened to take the case to the Supreme Court if necessary. Fortunately it wasn’t necessary. The city changed its mind. He still owns the house, and his pride in it is as great as it ever was.

When the Matures found they needed more space, they moved into a home in Mandeville Canyon. When he bought the house, a writer friend kidded him about it. “You’re the last person in the world I thought would ever go Hollywood,” she teased. “I hear you have a swimming pool, too!”

An embarrassed Victor rose to his defense. “We have to have more room,” he explained. “Besides, it’s just a house. It’s not so elaborate. And as for the swimming pool, well, Mike needs a place for him and his friends to swim.”

Victor thinks the world of Mike and the feeling is mutual. When he was making “Samson and Delilah,” Mike spread the word around the neighborhood about how Vic was going to tear down a temple with his bare hands. The other boys thought it rather a tall story. One evening Mike greeted Victor with a small request. He wanted a neighborhood demonstration. He figured if Victor would push the garage down it would do the trick. No one could fail to be convinced then what a great guy he was.

“Vic has more respect and feeling for home life than anyone in the business,” says one of his friends. “There’s nothing he likes better than coming home, barbecuing a meal and sitting around watching television.”

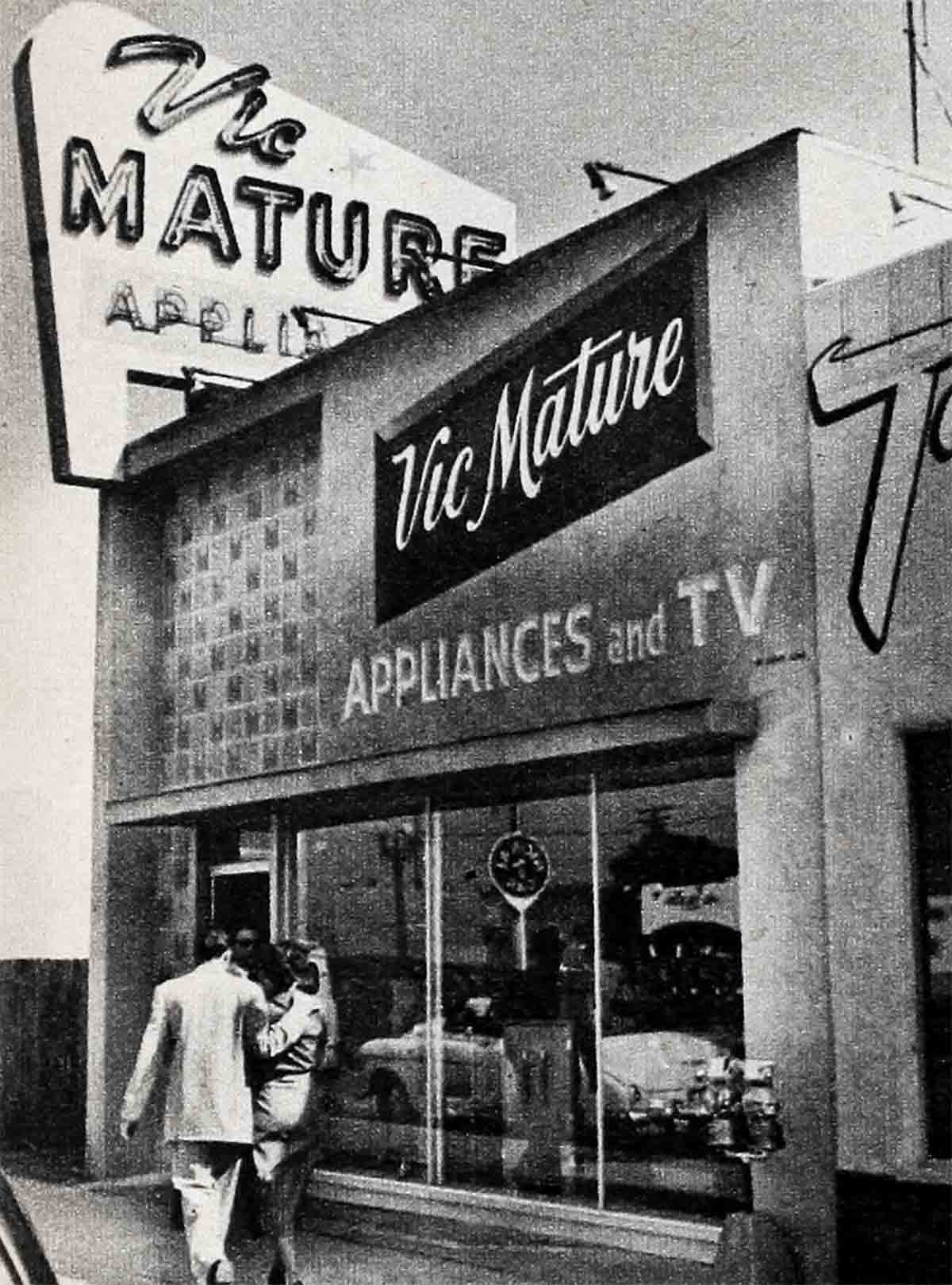

He’s rarely seen at a nightclub or premiere. Outside of pictures, he has other interests. For one, a TV appliance store. And he works at it. At one point, the salesmen were claiming that he was selling more television sets than his sales force. “He comes in quite a bit to keep an eye on things,” says Bob Graham, Vic’s store manager and an ex-Commander in the Navy. “And he’s made a lot of practical suggestions which have helped business and the running of the store.” In short, Bo’s’n’s Mate Mature’s ship is in shipshape.

He keeps several TV sets in his studio dressing room so that whether he’s around or not, they will be available to everyone, come World Series or football time. He’s installed sets in the barber shops at RKO and 20th Century-Fox. He figures that the customers will enjoy them, and when they’re ready to buy their own, they’ll think of Mature.

He has other investments. “He’s a lucky man,” says one friend. “Everything he touches seems to turn out right.” When he invested in an oil well the well promptly gushed up some oil. It’s still gushing and shows no signs of stopping.

For relaxation, Victor plays golf. A friend from Texas took him out to a golf course one day and made him try the game. Victor’s been going back ever since. “He shoots in the low 80s,” says MacGregor Hunter, one of his golf pro friends. “Sometimes in the 70s. He plays with anyone who happens to be standing around with a club. And the man has stamina. He plays 36 holes a day easily, everyone else feels like dropping dead.”

“He starts early,” says Hank Barger of Rancho Santa Fé. “The caddies bring him taccos and enchiladas for breakfast between shots.”

He likes to win. Once he had a bet on the outcome of a game. However, after the first six holes, the sun began to go down. Vic promptly hired a truck to keep its lights on the ball, so that the group could finish the game. Vic and his partner won it. “He doesn’t always win,” says Barger. “But he’s in there pitching anyway—always trying his best.”

Victor explains it with his usual humor. “I hit the ball three hundred yards,” he’ll tell you. Then he’ll add, “A hundred and fifty yards out and a hundred and fifty yards to the right, out of bounds.”

His absence from headlines has perhaps increased the verbal remarks on his closeness with a dollar. Occasionally, he’ll help them along. For one thing, he doesn’t see much sense in the purchase of an expensive wardrobe. He’s no clothes hound. Often the studio wardrobe department will supply him with wearing apparal. Once, Victor was sitting with some friends in the patio of the Del Mar Hotel. He excused himself for a moment and left the table. A young girl, sitting nearby, came over. “Isn’t that Robert Mitchum?” she asked proudly.

Vic’s friends grinned and mumbled an answer that amounted to neither yes or no. When Victor returned, one of his buddies greeted him loudly, “Hi, Bob, glad to see you back.”

Then he explained away Victor’s look of puzzlement. Victor grinned. “She wasn’t just kidding,” he said. “She must have recognized the coat, from Mitchum’s last picture at 20th.”

He reached inside the coat pocket and pulled out a tag. “Robert Mitchum,” it read.

The matter of money is no joke with Mature. He’s seen too many stars throw around money and then, when their days of stardom are over, wonder what happened to it. “He respects money as any average American respects money,” says one of his friends. “And he’s careful with it.”

Yet he can spend it lavishly, if the cause is a good one. There’s the story of the time he started for Palm Springs with a thousand dollars. On the way he picked up some hitchhiking servicemen. Most of them were broke, so he remedied the situation. By the time he got to Palm Springs, he had to borrow some money from a friend for dinner.

He’s refused to squander his income since his first days of success, however. He bought annuities. “People like to talk about my financial affairs,” he’s said. “But I don’t care. I can’t help it. I can stand a little public interest. I was seven years in penniless obscurity.”

He’s grateful for his success, financial and otherwise. One Thanksgiving Day, he called his agent at home. “George,” he began. “I just wanted to call and tell you that I’ve been thinking about what I have to be thankful for. I have you to thank for being my agent and helping me in the picture business. I have my business manager, Robert Graham, to thank, too. You’ve both helped provide for my financial security. That’s given me peace of mind. And I’m very sincerely grateful to you both.”

Peace of mind—and yet no peace of heart. The divorce is in progress. Neither Dorothy nor Victor are happy about it. And there was even more unhappiness when the breakup came. Victor’s mother became ill and he flew to Kentucky to be with her. Then Dorothy’s father died and Victor caught the next plane back to Pasadena to help Dorothy and her mother through their difficult time. Two days later his aunt, who had been living with his mother, died of cancer and again Vic was called upon for help.

With the marriage over, Victor is alone again. Perhaps he’ll go on being alone. Or perhaps it’s as a surprised Rita Hayworth said during their courtship days. “Why, Vic, you’re the loneliest man in the world. You pretend to be gay. You run away from serious things and love. But you can’t go on doing it forever. Because until you find a real and lasting thing, you’ll have no happiness.”

He’d thought he’d finally found it. But he’s lost it again. And what comes next? Hollywood remembers another story. Of the time he played Samson. In the picture, he licked the entire Philistine army with the jawbone of an ass. “After that,” he grinned, “I should be able to lick any problem.”

Maybe he wasn’t kidding.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955