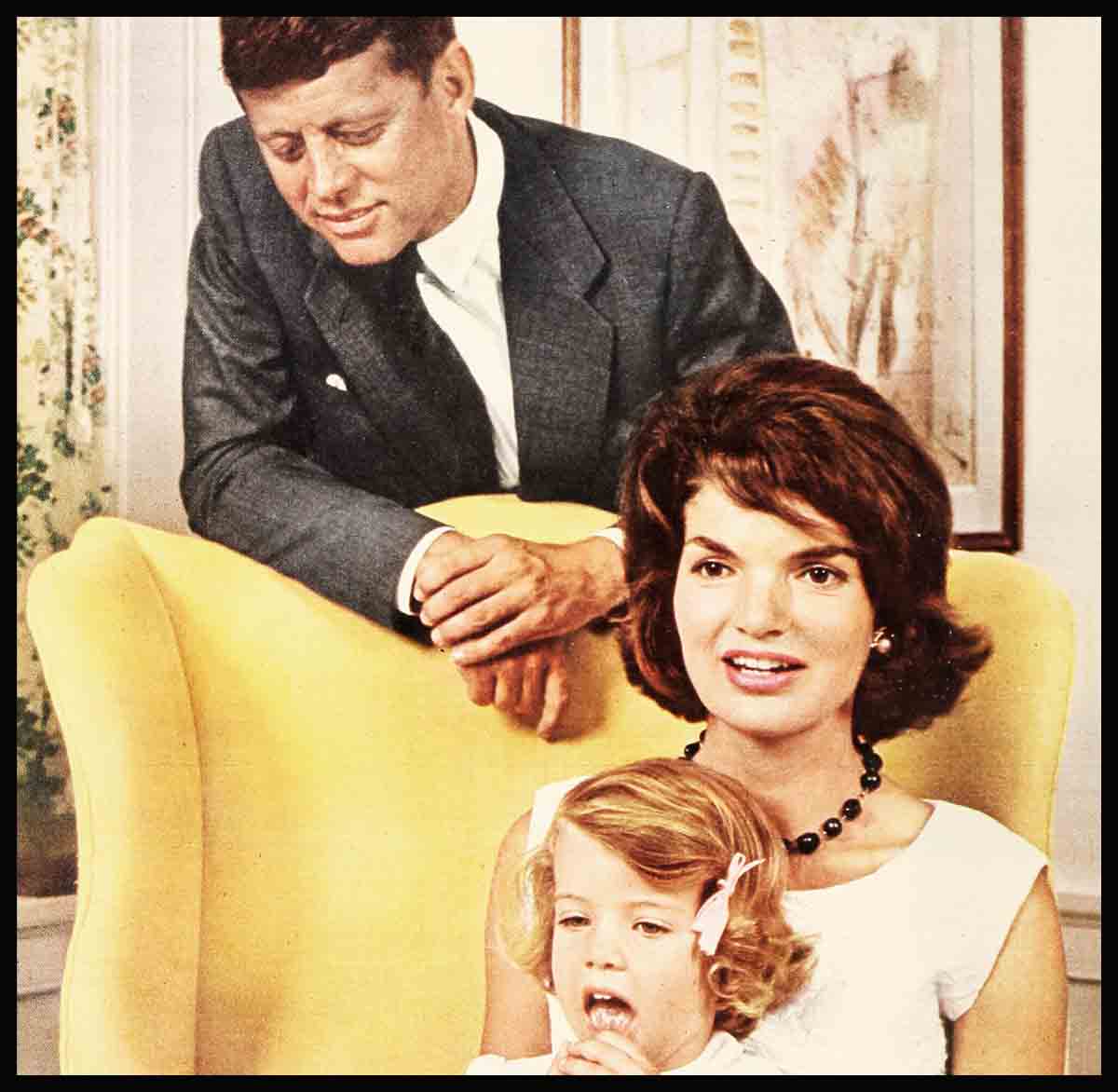

The Love Story Of Jackie and John Kennedy

It was a night in 1951. Jacqueline Bouvier was twenty-one. She lived in Washington, D. C., and worked as a reporter-photographer on the Times-Herald. She had the reputation of being one of the prettiest, quietest and best-dressed young women in the capital, and (because of her job, mostly) of always arriving late at parties. She arrived late, as usual, this night.

“I wish you’d hurried it up a bit, Jackie,” her hostess said, taking her coat. “There was a young man I wanted you to meet. And now you’re here and he has to leave.”

“Who has to leave?” Jackie asked, politely, if not with much curiosity.

‘‘Him,” the hostess said, a flutter in her voice, as she indicated a tall, sandy-haired, good-looking young man who stood on crutches on the other side of the room.

Jackie recognized “him” immediately as Jack Kennedy—Congressman, candidate for the Senate, Purple Heart hero (he’d injured his spine, badly, in World War II).

“Come on,” said the hostess to Jackie, taking her arm, “at least you two can get to say hello. . . .”

Jackie blushed as Jack looked her in the eye.

“I don’t mean this as a line, Miss Bouvier,” he said, beginning their first talk together, “—but haven’t we met before?”

“Well, sort of,” said Jackie. “That is, I covered a press conference you once gave. There were about fifty reporters. You shook hands with most of them. But you only got to nod at me.”

“Bad luck for my side,” said Jack, beginning to laugh. “I—” he started then.

But at that moment someone came over to him and whispered something.

“No,” Jack said.

“Yeah,” said the other party, pointing to his watch.

“I’m sorry,” Jack said, turning back to Jackie. “I don’t want to go, but I’ve got to.”

“Of course,” said Jackie.

“I’ll see you again, though,” Jack asked, “won’t I?”

“Oh . . . sure. Yes,” said Jackie.

She was glad he turned around right after that, and started to say goodbye to some other people.

It was terrible the way he was making her blush. . . .

They walked through the soft darkness of the garden, the party—the laughter and the music—behind them. They walked slowly, both of them silent. They walked until they came to an old stone bench and Jack lay down his crutches as they sat.

“Why’d you look me up . . . after a year, a whole year?” Jackie asked, suddenly. “Why’d you invite me out tonight, here, to this party?”

“Because I liked you,” Jack said. “Because I remembered you.”

“That’s very flattering, you know,” said Jackie, “coming from a United States Senator.”

“Let me ask you something,” said Jack.

“Yes?” Jackie asked, clasping her hands.

“Why’d you want to come out here, and leave the party? That was a pretty good party in there.”

Jackie looked down, at her hands.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I guess it’s that I don’t like crowds much.” She looked up suddenly, concerned. “If you want to go back—” she started to say.

“No,” said Jack. “We can always sit out here in the moonlight and have a nice quiet talk about . . . about Mr. Eisenhower. Or Mr. Nixon or Mr. Stevenson, and his chances in ’56.”

Jackie scanned his face in order to see whether he was serious or not.

He wasn’t.

“Or,” said Jack then, “you can start now by telling me about yourself . . . I want to know about you.”

“Me?” Jackie asked. “What do you want to know about me?”

“Everything,” said Jack.

“Well,” said Jackie, “I was born in New York. I went to school there. I went to Vassar for a while, too, then to the Sorbonne, then back to Vassar. I couldn’t stand it when I got back the second time, from France, the way they treated us like a bunch of children. At Vassar, I mean . . . So I left.”

“Uh-huh,” said Jack.

“Now,” continued Jackie, “I work on a newspaper; as you already know; I read lots; I devour books—mostly books dealing with the Eighteenth Century; that’s my favorite, the Eighteenth Century. I used to paint, used to love it, but I wasn’t much good at it, so now I just look at other people’s work—I’m forever going to galleries.” She paused. “I’m not a very good cook; mainly because I don’t eat much myself, I guess. I like the color blue, and I don’t mean baby-blue or na blue, but real blue, like the color of the sky on an almost-perfect day . . . And what else? I don’t like jewelry. I don’t like hats. I can do without fur. I speak rather fluently in Spanish, Italian and French . . . And that, I guess, is me.”

“Pretty good,” said Jack, “except you left out a few vital categories.”

“Like?” Jackie asked.

“Like do you enjoy swimming?” asked Jack.

“Kind of,” Jackie shrugged.

“Do you like to play touch football?”

“What?” asked Jackie.

“Do you know any good jokes?”

“I forget them all,” she said, “the minute after I’ve heard them.”

“Do you like clam chowder?”

“Honest answer?”

“Honest answer.”

“I loathe clam chowder,” Jackie said.

Jack groaned.

“What’s the matter?” she asked.

“Just that you’ve chucked out all your fun for this weekend,” Jack said. “Here I am, about to invite you up to the Cape, to come visit my family, and now I think you’re going to end up having a dull time there. Why, you don’t answer yes to any of the presently established ground rules.”

“This weekend?” Jackie asked, worried suddenly. “Ground rules?”

“Ground rules-for-a-Kennedy-weekend,” Jack said, nodding. “Very famous in Massachusetts.”

Then he recited them:

“First thing you go for a swim.

“Then, you sit with the family and tell at least three good jokes.

“Then, you say ‘Terrific’ when you taste the clam chowder at lunch—the pride and joy of all New England.

“And ‘Terrific’ must be your response when asked to participate in an early-afternoon game of touch football. Now, about this game—”

On and on Jack went, laying ground rule after ground rule.

And then, when he was finished, he took Jackie’s hand suddenly in his, and he asked, “Will you come, this Saturday?”

“Saturday? . . . This Saturday? . . . Yes, . . . I guess,” Jackie found herself saying.

“You want to know something?” Jack said, then. “You, Miss Bouvier, happen to be the most beautiful girl I’ve ever met.”

“Really?” asked Jackie, vaguely, as she sat there, happy on one hand that this man she’d been g about for over a year now had asked her to spend a weekend with him, but worried on the other hand about the family she’d soon have to meet, and about what they’d think of her. . . .

THE KENNEDYS—all twenty-eight of them—fell in love with Jackie Bouvier that weekend in Hyannis Port. And, best of all, and most of all, Jack fell in love with her.

Back in Washington, following the weekend, he saw her almost constantly.

And, finally, one night, he asked her to marry him. . . .

The wedding took place on September 12, 1953, at St. Mary’s Church in Newport, Rhode Island. The reception was held at Hammersmith Farm, an oceanside estate owned by Jackie’s mother and stepfather. And all of the guests agreed it was a perfect marriage.

But, it didn’t go well for the Kennedys; not at the beginning.

Deep down, Jackie had expected some sort of normality in her marriage. Not as far as her outside activities were concerned; she’d known about the social functions she’d have to attend, the handshaking sessions, the receptions, the teas—the giving up of many, practically all, of the quieter activities she had loved so much.

But she had expected another kind of normality. She’d wanted, most of all, to have a home, and to have her husband in it. She got the home—but her husband, Jack, the Senator, was rarely in it. In fact, he was becoming so popular with Democrats all around the country that, aside from those times when Congress was actually in session, he was rarely even in Washington.

Jackie tried to joke about this at first.

“My husband,” she said once, “thinks nothing of buying a shirt in California, a toothbrush in Kansas, and a tube of toothpaste in Pennsylvania. I think it’s funny don’t you?”

For a while, Jackie even tried to do the traveling bit with Jack.

She tried getting used to closing up the house at a moment’s notice.

Getting used to trains, busses, planes, more planes.

She tried getting used to packing, unpacking.

Getting used to sitting alone for hour after hour in strange hotel rooms while her husband went on with his business.

She tried all this, right up until the time she became pregnant.

He’d just completed an exhausting tour when suddenly another presented itself.

“Would you mind if I left?” Jack asked Jackie.

“No,” Jackie said.

Was she lying, if herself, to Jack?

She didn’t know.

She didn’t know she told herself.

But then, a few days after Jack left—that moment on the beach—then she knew. . . .

She was at her mother’s place in Rhode Island. It was late afternoon, foggy, a slight chill in the damp air. She was walking along the beach, slowly, alone.

Suddenly she stopped. She felt the pain, the unbearable pain, in her stomach. She felt the nausea, the terrible feeling of nausea, overtake her. And she felt the sweat, that came rushing to her face, despite the chill in the air.

“Oh no,” she said, as the pain grew worse. “Oh no.”

She fell.

She knew what was happening. Her baby, she knew, was dying inside her.

“Oh no,” she said.

“No.”

She lifted her head.

Her eyes began to shift, wildly.

She looked straight ahead, at the long stretch of lonely beach.

She looked to her right, at a silent dune.

She looked to her left, at the calm and vast expanse of ocean there.

“Jack, Jack,” she began to whisper.

She dug her fingers into the sand.

“Jack,” she asked, “where are you?”

SHE MADE UP HER MIND as she lay in the hospital room that next morning. Jack was flying back, he would be there soon; and, she made up her mind, she would tell him, right as he came through the door.

“I don’t want this any more,” she would say, “as soon as your term is up,” she would say, “I want you to leave politics. For good.

“Our baby is gone, Jack,” she would say. “I’m going to be lonelier now than I ever have been. Don’t you keep leaving me, too, Jack. Not you, too. Not any more.

“Let’s be,” she would say, “like other people. Let’s go away, Jack. Oh, to be able to go away. And breathe real air. And have no more of this, this life, this cloud we try to breathe through, to walk on. To is somewhere else where we can hold on to something. Really hold on to something.

“I heard them before, in the room next door,” she would say. “The woman had her baby. Yesterday, a little girl, I think it was. And he came; her husband. I could almost smell the flowers he brought to her. He sat with her all day. All day. He didn’t have to leave. And they sat together. They talked, and they laughed. And there was no place else for him to go, to rush to. They just sat together. The wife. The husband. e baby. . . .

“Our baby,” she would say. “Oh Jack . . . I didn’t care if it was a boy, or a girl. Did you, Jack? I only wanted a baby. Our little boy or girl. And now—” she would say.

“And now.

“And now—”

She turned her head on her pillow.

The door, she could hear, was opening.

“Jack?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said.

She looked at him as he walked towards her, slowly, limping on those crutches the way he did. She looked at his face. She had never seen him look so haggard before, so sad, so frightened, so worried.

“Jack—” she started to say.

“Jackie, are you all right?” he asked.

“Jack—” she started again.

But she continued looking at him, and she stopped.

“No,” she thought to herself. “Not now. I won’t tell you now. But someday soon. Very soon. . . .”

THE DOCTOR, a friend of the Kennedys, wasn’t surprised that Jackie looked shocked. He’d had a hunch Jack hadn’t told her about the operation yet. He’d thought it time somebody did.

“You see,” he said, “when your husband was a kid he hurt his back playing that danged touch football they’re always playing up there at Hynannis Port. Then in the war—well, you know the story, Jack on the PT boat, the Jap destroyer ramming into the boat, slicing it in half, Jack landing on his back again . . . He’s been in bad shape ever since. Now, slowly, things are getting worse. There’s a chance, Jackie, that if he doesn’t go through with this thing he may end up a hopeless cripple . . . He doesn’t want that. He wants anything but that.”

“And, if he does go through with hee Jackie asked.

The doctor paused for a moment.

“Jack’s been suffering from an adrenal depletion,” he said then. “Adrenalin protects the body from shock and infection. An adrenal insufficiency greatly increases the possibility of infection and hemorrhage during surgery. I’ve warned Jack that . . . that his chances of surviving the operation are extremely limited.”

Jackie gasped.

She tried to say something.

She couldn’t.

“You’ve been pretty tense these past couple of months, Jackie,” the doctor said. “I know a miscarriage can do it to any woman. . . . But I want you to snap out of it, Jackie. For Jack’s sake. That’s why I’m telling you what he hasn’t told you . . . I want you to cheer him up as much as you can now. He’s not saying anything, but the pain, the mental anguish, together they have him going through hell . . . And I want you to relax now, to try to be your old self. For these next few days, at least, Jackie.”

“Next few days?” she asked.

“Today’s Monday,” the doctor said. He looked over at his calendar. He nodded and circled a date: October 20th, 1954. “The operation’s Thursday,” he said.

That night they talked.

JACKIE HAD JUST TOLD JACK about her talk with the doctor that morning.

Jack shook his head.

“He shouldn’t have said anything. It wean right. I should have told you,” he said.

“You would have put it off, till tomorrow, till Wednesday.” She took his hand. She tried to smile. “I know you,”she said.

“I wanted to tell you my way, though,” he said. “There were so many things I wanted to tell you . . . my way.”

“There’s nothing to tell me,” she said, “except that you’re going to have an operation and that everything’s going to be all right.”

“There were other things, though,” he said.

“What things?”

“I wanted to tell you, Jackie . . . . how much I love you.”

“I know that, silly,” she said.

“And I wanted to thank you, too.”

“For what?”

“For what you’ve had to put up with these past couple of years; the way you’ve put up with everything,” he said.

“Jack—”

“I wanted to tell you what a wonderful wife you’ve been, a wonderful sport . . . I know,” he said, “I know that it’s been hard on you, Jackie. I know there’ve been times another girl would have thrown in the towel. But—”

She forced herself to laugh a little. “But I’ve been a real brick about this whole thing, haven’t I?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said, laughing a little, too, “yes . . .

“You know,” he said then, after a moment, the laughter gone, “this has been a strange day for me. I tried to work today. But for the first time in a long time I couldn’t. I sat at my desk and I started to think. Not about the operation. But I started to think about my brother. About Joe. . .

“Have I ever talked to you much about Joe, Jackie?” he asked.

“A little, sometimes,” she said.

Jack smiled, and he put his head back on his pillow.

“He was the oldest of us all,” he said. “And he was the best . . . He was handsome, Joe was. And he had brains, and character, and guts . . . And we loved him. Idolized him. Thought him our own private saint, we did.

“And he used to say, when he was just a kid, I remember, he used to say that he would grow up someday to be President of the United States. ‘I’ll settle for nothing less,’ he would say.

“He meant it, too. If he’d lived, Joe would have gone on in politics, and he would have been elected to the House and to the Senate, like I was.

“. . . He never got the chance, though. The war came. He was a Navy pilot. He flew out from England. He finished one tour of duty. He was eligible to come home. But he stayed for a second tour. He wanted to be there for D-Day, he said.

“Then, after that second tour, Joe was eligible to come home again. But he heard about an operation, something to do with knocking out the German V-2s. He heard about this the night before he was to leave. His luggage was already on a transport ship, ready to leave for New York.

He got them to take the luggage off. And the next day he got into his plane and set off on a mission.

He must Have been up thee an hour, over France, when the plane exploded.

“Joe was killed.

“They never found a trace of his body. . . .

“Me, Jackie,” he went on, after a pause, “me, I wasn’t the same as I am today before Joe died. I’m like Joe today—at least I try to be. But before he died I was a shy guy, shy and quiet. Nobody in the world could ever picture me as a politician. Everybody was sure I’d end up being a teacher, or a writer.

“BUT I WENT INTO POLITICS because Joe died. He was gone and I was still here and it came very naturally to me that I would take his place . . . After a while, I got to love politics. It became my whole life—the way it would have been Joe’s . . . But at the beginning I didn’t do it for myself. . . .

“I come from a strange family maybe, Jackie. We’re very close. And we have a hero. We loved Joe while he lived. And we honor him now that he’s dead . . . And just as I went into politics because Joe died, if anything happened to me, if I died, my brother Bobby would run for my seat in the Senate. And if Bobby died, Teddy would take over for him.

“That’s the way it’s got to be, Jackie.” He turned to look at her again. “That’s the way it’s got to be.”

“I know,” she said.

“I may die, you know, Jackie,” he said then.

“Please, Jack—” she started to say.

“And if I do,” he said, “I just wanted you to hear this story, in case you wondered about me, why I spent so much time doing what I had to do . . . I know,” he said, “that it’s been hard on you—”

“Please, Jack—”

“I know there’ve been times, like when you lost the baby—”

“Jack!” She began to sob suddenly. “I don’t care about me anymore. Don’t you understand? I only want you, Jack. I only want you to live. I want you to live.”

“I’ll try,” he said, “with every bit of strength that’s left in me.” He smiled again. “Don’t you go worrying about that, Jackie.”

He smiled.

“ I’ll try,” he said, “. . . . for you, for me, for the family we hope to have someday, for the good life I owe you, my Jackie . . . my sweetheart. . . .”

And later, much later, when Jack was asleep, she got on her knees, and she prayed, with tears in her eyes, that the miracle would be.

. . . It was.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1960