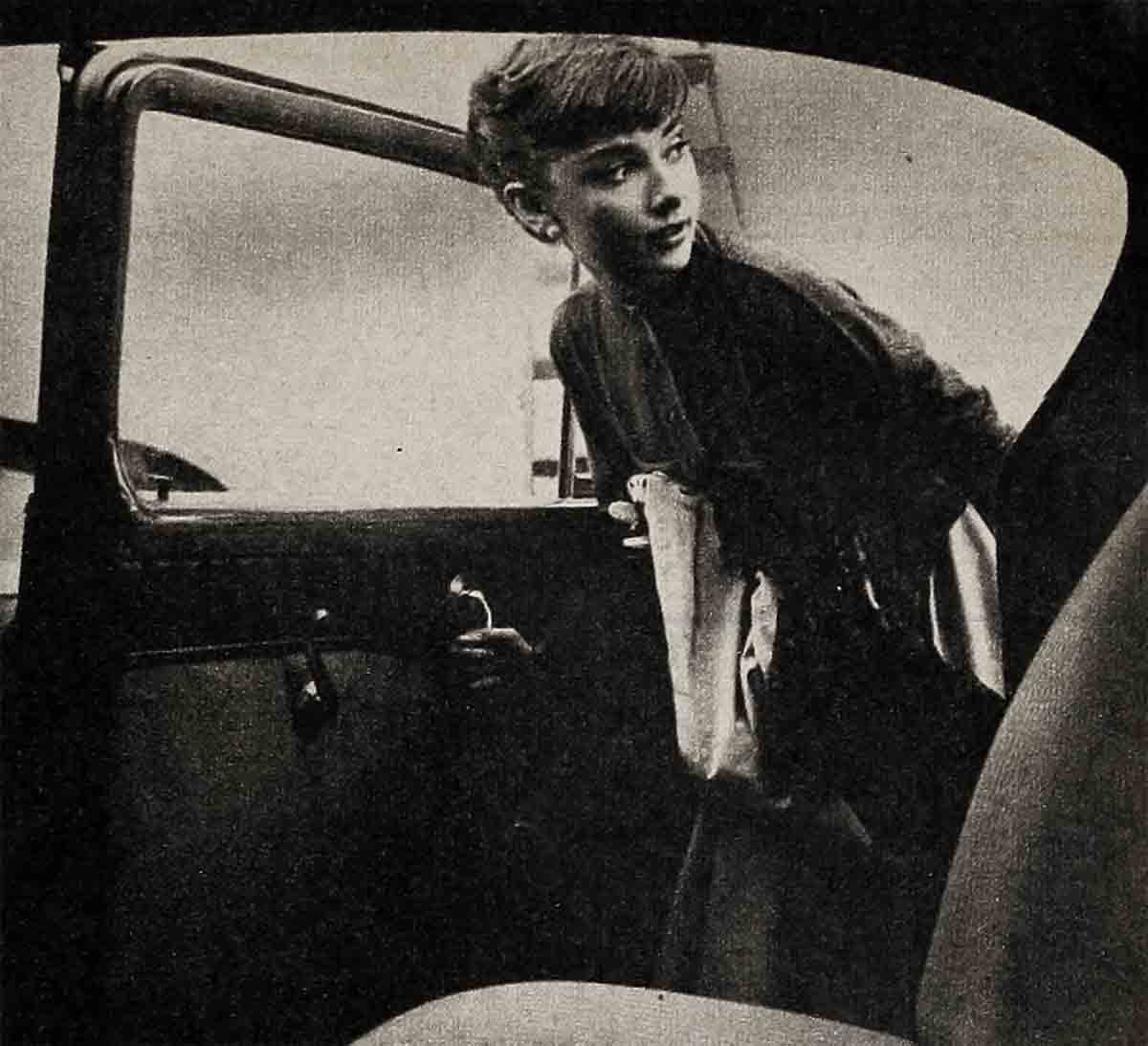

Dutch Treat—Audrey Hepburn

One fine spring day, a few years ago, a slim, fifteen-year-old girl called Edda van Heemstra slipped on a sunsuit and crept out of the cellar of her house near Arnhem, Holland, into the garden where she wasn’t supposed to be.

She breathed deeply and, because she hadn’t sampled any fresh air for weeks, she found it intoxicating. Then she stretched out on a pad in the sun and the bees in the orchard blossoms buzzed her to sleep. But she dozed fitfully because in her dreams the “whump, whump, whump” of artillery seemed to march up the River Rhine right to her garden which was smack in the Nazi battle lines. Only when the earth shuddered beneath her and a blast tumbled her off the pad did she wake up and realize this wasn’t her routine nightmare. It was real. Bits of gravel peppered her skin and shell fragments whined wickedly past her ears.

Edda dug the earth with her nails. For agonized seconds she quivered there expecting to be blown to oblivion. Finally the barrage moved on and she crawled back to her cellar door, shaking. She never wanted to try that again.

Edda van Heemstra shed her Dutch alias after the war. She uses her real name now—Audrey Hepburn.

Last October Audrey faced another kind of bombardment in Hollywood where she was making her first American movie, Sabrina Fair. This time the big guns could be labeled Skepticism, Challenge, Envy and Resentment. They were loaded, aimed and set to wham away at her. After all, Audrey was a foreigner, also a one-picture sensation with a royal aura collected in Roman Holiday. She was young and deliciously attractive. Worse than that, she was extravagantly hailed as the new wonder of the film world. There were rumors of attractive Hollywood men like Gregory Peck and Kirk Douglas going mushy over the girl abroad. What a target!

But the battery never opened up. Audrey spiked it. When she flew away to Broadway in December, Hollywood had capitulated. Audrey Hepburn did more than conquer Hollywood. She enchanted it.

Humphrey Bogart, who usually snarls at his colleagues on the set, especially if they seem high and mighty, cooed like a turtledove when Audrey was around. He gave a dinner party in her honor and Baby Bacall loved her. Hepburn’s other co-star, William Holden, who can be belligerent about his privacy, even served tea (which he hates) to Audrey and her friends in his dressing room. Bing Crosby, who never visits any sets around Paramount, visited Audrey’s like a little boy lost with the excuse that he wanted to keep his French from getting rusty. Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, on one side of Audrey’s dressing room, lapsed into reverent sanity for the entire two months. Danny Kaye, on the other side, confined his brash gags to one mild attempt. “I’m going to bore a hole through this wall,” he threatened. “How nice. Please do,” invited Audrey.

No one was exempt from Audrey Hepburn’s amazing spell. Director Billy Wilder, who spends his days prodding stars into performances over their heads, raved, “She’s Mickey Mantle. She can do anything. There’s no one like her.” Hardbitten grips, props and juicers conducted themselves like courteous pageboys around Audrey. “I don’t know exactly why,” one confessed. “Here this kid has the red carpet rolled out all over the place, and ordinarily that’s a sickening sight to a working stiff. But for her it looked right.” Disillusioned Paramount press agents mooned like schoolboys and dug the dictionary for high flown adjectives. They produced “mesmerizing, fey, stately, elfin, wise, ravishing and vibrant.” Everyone else on the Paramount lot, from studio chief Don Hartman to the lowliest messenger boy, sang praises and cooked up excuses to collect a glance from her tilted eyes or a phrase from her Mona Lisa lips. Cynical reporters arrived primed to debunk Audrey and departed as putty-noodled as the news-hawk Greg Peck played in Roman Holiday—and with blank notebooks.

During her entire Hollywood stay, Audrey Hepburn said and did nothing provocative enough to make the “Personals” column of a weekly paper. She never entered a nightclub. She attended four dinner parties—at the Bogarts’, Jack Bennys’, Billy Wilders’ and Stewart Grangers’. She went to the Ice Follies and the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. On these occasions, Audrey’s escorts were men much older than she. Groucho Marx took her to Bogey’s and Bing Crosby to Benny’s. Funnyman Phil Silvers beaued her to the ice show. Audrey took herself to the ballet.

She did nothing more startling than wearing pink matador pants a time or two and riding around the Paramount lot on the green bicycle Billy Wilder gave her. A studio limousine whisked her to and from a modest two-room penthouse apartment on Wilshire Boulevard, where the only verified steady visitor was a stray cat. There she cooked most of her own meals and usually sacked in from Saturday to Monday watching TV, listening to records, snoozing and reading scripts. Her free days around Paramount she trotted over to the dance barn and worked out with ballet exercises. A couple of times she went swimming in Jean Simmons’ pool.

In short, about all Audrey Hepburn did in Hollywood was to make Sabrina Fair. By the time she left she was the most talked about actress in modern Hollywood history.

How come? What is this Hepburn magic? How can a girl on the spot spend nine weeks in a sensation-jaded place like Hollywood and, by doing nothing spectacular, leave it babbling poems of praise in her wake? How, for instance, could she make a glamour-gorged guy like Bill Holden get lyrical about her “elegance and fascinating formality?” Or a vet like Joan Crawford, who only caught a glimpse of her, call her “the greatest thing to happen to Hollywood in years.” How, for that matter, could fans all over the land boost Audrey to the top boxoffice ten after only one picture? What’s the girl got?

A first impression of Audrey is that the girl could stand a square meal. Five, seven, but only 110 pounds and with a twenty-inch waist, Audrey sports nothing up and down her chassis that would make the boys in the front row cheer. She wears a size eight shoe and she has a small face perched on a long, gazelle-like neck. She holds her back straight and her slightly slanted nose seems always to be pulling everything up. She looks like one of those Pharaoh’s daughters on an ancient papyrus scroll.

Looking at Audrey carefully. you can see that her teeth are not perfectly aligned, her nostrils flare and her dark hair seems to be carelessly cut. She has deep brown oversize eyes that come across in a curve, high and outside. Her black eyelashes are long and the thick eyebrows are perfect. The effect adds up to a new deal in Hollywood glamour. Neither pure beauty nor raw sex is what Audrey Hepburn gets across. Her personal charm is elusive, sophisticated and subtle. It’s continental but cute—dignified but disarming.

Audrey is gracefully informal. She takes you in but holds you off. The Dutch treat with the English accent talks well but tells nothing. If you ask a personal question she smiles sweetly and is silent as the sphinx. You wonder how you could ever, ever have been so gauche. She can sit as primly as a princess, wearing a suit by de Givenchey and kicking off her patent leather pumps to reveal pink toenails peeping through her nylons. It seems so correct that you wonder if you shouldn’t kick off your own shoes. She can slop her coffee over the cup and it looks as though that’s the only proper way to handle a teacup. She’s in command of every situation all of the time. Audrey’s undeniable attraction, in one word, is presence. Most Hollywood stars affect it but never quite attain it. That’s why Audrey Hepburn has bowled them all over. With her it comes naturally, as it does with some other girls known as princesses. Playing a real one flawlessly, of course, is what brought Audrey to Hollywood.

Because that stock title sheet line, “resemblance to any living person is purely coincidental,” is a joke when applied to Roman Holiday. Its common knowledge that the story was inspired by the English Princess Margaret’s frolics on the Isle of Capri and the picture was released when the rebellious young lady’s romance with Commoner Peter Townsend was hot news. Choosing Audrey Hepburn to play Princess Meg on the screen was a happy piece of casting. In Roman Holiday you watched Audrey romping around Rome but you were also seeing Margaret Rose.

It wasn’t all illusion. Audrey’s resemblance to Princess Margaret was good luck. But a lot of what came across in Roman Holiday was the result of the same sort of disciplined, tutored childhood that the British princess had.

Audrey’s mother is the Baroness van Heemstra, of a noble Dutch family. At one time their ancestral castle was Doorn, where the exiled Kaiser Wilhelm spent his last years chopping wood. Audrey’s ancestors served Holland’s royal house for generations. One of them, Baron Aernoud van Heemstra, governed the colony of Surinam for Her Majesty, Queen Wilhelmina. A cousin was adjutant at the royal Dutch court. Audrey’s father was J. A. Hepburn-Ruston, an Irish-English businessman. Her parents were divorced when she was ten, and since then Audrey has had practically no contact with her father, who lives today in Ireland.

Audrey Hepburn was born in Brussels on May 4, 1929. Her first memories are of a big comfortable estate outside Brussels with servants, governess, pets and plenty of room to race around, playing with her two older half-brothers, by her mother’s first marriage. Serious whooping cough almost killed her at six weeks. Later, she became a skinny kid, but healthy and never coddled for a minute. Her program was rigorous. She learned French as well as English. At four she was sent to school in England as her parents shuttled between the British Isles and Holland. Audrey’s clothes were especially made for her; her behavior carefully coached. She was introduced to opera and ballet as soon as she could sit still in a theatre seat. She traveled all over Europe with her parents.

This left little time for play or such frivolities as the movies. “I never knew what a ‘fan’ was or what the word ‘star’ meant until I made pictures myself in England,” Audrey confesses. “Until I was eighteen I had seen only three—and they were Austrian or German.”

So you couldn’t call Audrey Hepburn’s childhood normal in the American sense. It was sheltered in the aristocratic European manner, with emphasis on training in the arts. There was something to study and master every minute. Soon a determined passion for ballet dancing and then the war made her all but isolated.

She had started dancing classes at five. At ten she attended a performance of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet and walked out with visions of a ballerina’s career dancing in her head. But the thunderclouds of war were already rolling up, and before them the violent gusts of political struggles. They swept away Audrey Hepburn’s security. Her father joined Sir Oswald Mosley’s Fascist Black Sbirts. Her mother soon divorced him and took Audrey back to Holland and the family home outside Arnhem. Then one day the Nazi tide swept across the Low Countries and remained for six years.

At first the conquerers were painfully correct. Audrey’s life went on about as planned. She studied violin, piano, singing and, of course, dancing. She was one of the first pupils at the Arnhemse Danss-school, whose leading ballerina, Madame Winja Marova, still sighs regretfully, “She should never have entered pictures. A fine ballerina was lost.” Maybe so. Certainly Adriaantje (Dutch for “Little Audrey,” as they called her) was as graceful as a sprite and for a long time lived the almost cloistered life of a ballet novice. Soon she used her dancing in another way—to help raise money for Dutch resistance.

The Nazi screws tightened. Hobnailed boots clattered over the brick pavements at night and people Audrey knew vanished as the terror spread. Her cousin was executed and her uncle was shot for implication in a sabotage plot. Audrey changed her name to Edda van Heemstra and spoke only Dutch in the streets. At night she slipped out to verboten gatherings at homes of underground leaders, dancing and passing the hat for money to help carry on the resistance. By day, sometimes, notes that could have sent her to prison nestled in the toe of her stocking—messages to Dutch underground leaders.

Understandably, Audrey Hepburn doesn’t like to talk about those days. Besides the Nazi terror there was the hunger and cold, the desperate problems of trying to exist in a plundered land. The winters were bitter with no coal and often only runty greens to eat. Audrey still drools when she sees rich food—but she still gets a stomach ache when she eats it.

The worst time of all came right before liberation. Around Arnhem hopes leaped wildly when the British picked that town for the first airborne landing. The Union Jack came out of hidden places and people cheered as Tommies dropped from the skies. But somebody blundered. A Nazi panzer division, undetected, was waiting and moved in. It massacred the British in one of the greatest fiascoes of the war.

“After that,” remembers Audrey, “we lived in a ghost town, although you couldn’t say we lived. We stayed alive.”

The Germans evacuated the city, taking everything. Arnhem was dead. Audrey’s house was outside Arnhem, right in the German lines. For seven months she huddled with her relatives in the cellar as bombardments made the earth heave around her. She risked her life every time she popped her head out. That’s when the craving for fresh air overcame the fear of being blown to bits and she took that sunbath and almost got killed.

In April, 1945, Arnhem was liberated by General Montgomery. Audrey could breathe again, but she was a different person. Maybe it’s that background that makes Audrey Hepburn a baffling personality in Hollywood, surprisingly mature in some ways and shyly naive in others.

Things were easier for Audrey Hepburn after V-E day, but the family fortune was wrecked. Her mother went to work as a decorator helping to restore ruined Dutch homes. Audrey went back to ballet school. She studied in Amsterdam and The Hague, helping to pay her way by working as a fashion mannequin. At nineteen, when she had made enough progress and saved a small stake, she went to London alone to try out for Madame Marie Rambert’s famous advanced ballet school. She bought a round trip ticket in Holland, but tight money restriction allowed her to take only five pounds—then about fifteen dollars. Madame Rambert took her into her own house with some other promising pupils. There was no money from home. To keep her body, soul and ambition together Audrey didn’t act like either a princess or a prima ballerina. She acted like a chorus girl.

Audrey landed first in the second row chorus of the English production of High Button Shoes. Even in that obscure spot, both her grace and appeal stood out. She kicked her willowy legs in other spicily titled revues like Sauce Tartare and Sauce Piquant. She picked up jobs in night clubs and bits around London’s movie studios. It was a big moment for Audrey Hepburn when she actually played a talking bit—as the cigarette girl in the opening shot of The Lavendar Hill Mob.

She landed a honeymooning bride bit in a minor British film romp called Monte Carlo Baby, mainly because she could handle both the English and French versions. That took her on location to the gamblers’ Principality of Monaco. The day Audrey played her quickie role in the lobby of the Hotel de Paris she also hit the jackpot.

The aging French author, Colette, whose novel, Gigi, was being dramatized for Broadway, spied Audrey from her wheelchair. There was the teen-age heroine of her sophisticated book. “There’s Gigi,” she said. Colette was right.

A few months later Audrey opened in Gigi at the Fulton Theatre in New York, playing the title role. She had never before acted on the stage. Besides a few dramatics lessons in London she had no training for such a debut. She had never been to America and knew no one. The pressure on the twenty-two-year-old untried, unknown girl was terrific. If she flopped . . . ! But Audrey Hepburn didn’t flop—she made a hit. The first night, walking off stage, the manager complained, “I don’t know how you’re going to get inside your dressing room. It’s full of flowers.” When Audrey did get inside there were Helen Hayes and Marlene Dietrich, fabulous names to her, waiting to hug and congratulate her. Critics raved about the new star. They’ve been raving ever since. It looked easy for Audrey Hepburn. But it wasn’t.

Butterflies fluttered in her flat tummy then. The next day Producer Gilbert Miller said, “Audrey, may I see you for a minute, out in front of the house?” She remembers thinking, “This is it. I’m going to be sacked.” Miller gravely walked her out under the marquee. Then he grinned. “Take a look!” Workmen on ladders were hanging up new letters. They spelled out, “AUDREY HEPBURN.”

Later in London director William Wyler was poking around for a girl to play Princess Anne. He has said frankly, “When she first came to see me I thought she was skinny and colorless. I didn’t think she had a thing.” He granted a short film test anyway—the bed scene from Roman Holiday—but he wasn’t interested enough to stay in London and see how it came out. If the camerman hadn’t kept shooting after the scene and caught Audrey hugging her knees with a relieved giggle, Paramount might have scribbled “N.G.” on the effort back in Hollywood. But in that brief flash the real Hepburn charm came through and Don Hartman has a quick eye for charm. He cabled, “Sign her.” The butterflies are still with Audrey. “Every night is opening night to me,” she says. “After all, you have to deliver the goods.” They were there when she delivered the goods in Rome for a notoriously critical director, William Wyler, and in spite of a very sympathetic Gregory Peck. They were with her when she stepped on the set of Sabrina Fair. They’re with her right now on Broadway playing in Ondine. They’re always with Audrey Hepburn beneath her cool, calm exterior. They are with most champs. But they never make her lose her head.

Audrey Hepburn may become the biggest star in Hollywood, as William Wyler has predicted. Or she may be only a morning glory as far as Hollywood is concerned.

“This is the most trying time of my life,” she says. “I’m just a publicity star now. I’ve been made by good writers and directors, but I’m still a shadow. I can’t have substance until the public gives it to me.”

Well, the public gave it to her in both Gigi and Roman Holiday. But the sensitive European girl of Colette’s play was almost Audrey Hepburn herself. And so was hookey-playing Princess Anne of Roman Holiday. Will there always be naturals like that for her? The odds are against it. Audrey Hepburn is so extraordinarily fascinating because she is unique. First reports on Sabrina Fair, where Audrey plays a chauffeur’s daughter, say she’s every bit as enchanting as in Roman Holiday. But Audrey herself has admitted, “I haven’t any real acting ability. I’m still learning.” And her staunchest supporter at present, Billy Wilder, has said, “I don’t know. Maybe she’s too good for the general public.” In short, the jury is still out on whether or not Audrey Hepburn will continue to be a Hollywood sensation. There are a couple of other things that could line up against that prospect, too: Absence—and a heart that has no trouble growing fond.

Audrey left Hollywood last December and she may not return until 1955. That’s when her next picture commitment comes up at Paramount. Her contract binds her to only one a year and she has already made it for 1954. It may be a full year or more before Hollywood sees her again. Few great movie careers have been built that way. Audrey herself has shown no burning desire to concentrate on one. “I don’t want to stay in one place. I want to go everywhere and do everything,” she has said. “It’s the only way you learn.” One ambition is to do a musical in London or New York. That’s why, even as she made Sabrina Fair, Audrey worked on her dancing and singing.

Asked when she would return, she shrugged. “I don’t know. It depends on how long my play runs and whether I’ll make a picture in Europe after that or not. But I think I’ll take a holiday—perhaps in Italy, or in the south of France. Or maybe I’ll take a long trip.”

“Alone?”

Audrey smiled. “With my mother perhaps,” she said. “I might visit relatives.” Audrey still has relatives scattered all over, as far away as Indonesia where her two half-brothers, Ian and Alexander, work for the Royal Dutch Oil Company.

Since Christmas, Audrey has lived with her mother in a New York apartment. She has no other home. She isn’t planning to have either a husband or a home soon. Audrey is very positive about that in a general sort of way. “Not with a career,” she explains. “I don’t want a sloppy, long-distance marriage. You have to give up something.” If she does fall in love, she says, that will come first and a home and the hope of children will end her career—like that—the minute she says, “I do.” On her record, you might not buy that. But it’s a possibility.

Audrey Hepburn has already demonstrated that she is no cold potato beneath her placid poise. She has already been engaged to James Hanson, an attractive and wealthy young English businessman. She was picking out her trousseau in Rome during Roman Holiday. But when she went back to London—and returned to Italy for retakes—the marriage was off.

At the same time it was noted that Gregory Peck and Audrey were having fun together in the Eternal City, not all recorded by a camera. Greg was then estranged from his wife Greta—and people put two and two together. They didn’t quite add up to four and there’s no indication that they ever will.

The Pecks seem to have made up and Audrey says she didn’t even get a postcard from Greg in Hollywood. But if Audrey is as free as the birds right now, no one who knows her expects her to stay that way. Every man she works with gets gone on the girl and already rumors are that Mel Ferrer, her co-star in Ondine, is no exception. Audrey will be twenty-five this May and it’s hard to imagine her winding up playing The Old Maid.

But whether all these ifs and buts keep Audrey Hepburn away or bring her back to Hollywood, the town will never be quite the same. On her Hollywood holiday, Audrey may not have lighted up the playgrounds of the movie capital the way she revved up the ruins of Rome—but the general effect was the same. The girl who arrived on the spot left in the spotlight—simply by doing and being nothing but her own enchanting self.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1954