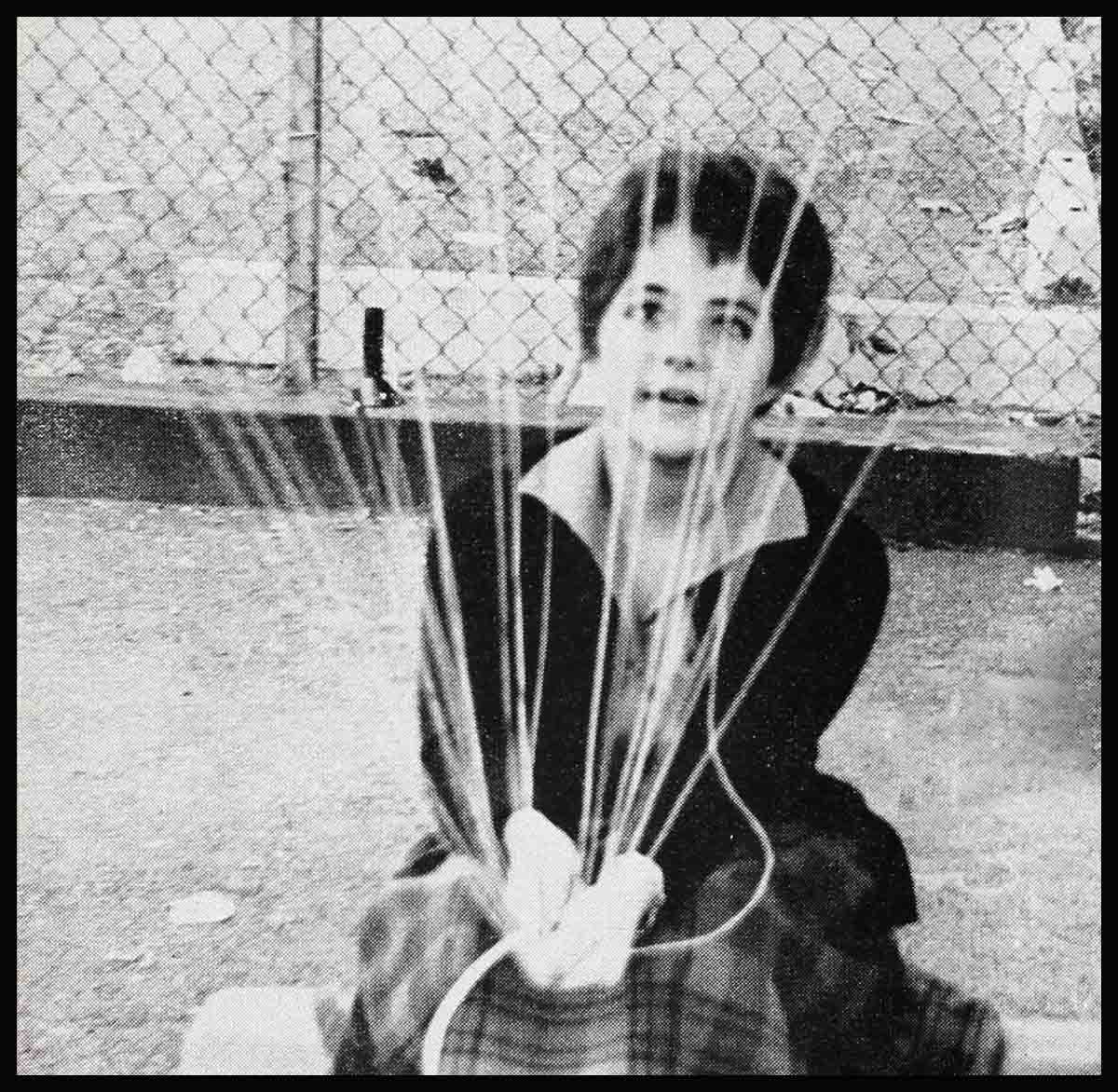

Believe It Or Not, This Is Brenda Lee

The halo of fluffy brown hair frames a round baby face with big innocent brown eyes and rosebud mouth. She stands four-feet-eleven and sits at considerably less. Stashed in one corner of a big easy chair, with her legs tucked under a billowing skirt and crinolines, she looks like a little doll. You want to pick her up and cuddle her. She looks up at you with a trusting smile and you want to protect her fiercely.

Then she opens the rosebud mouth. The voice comes out ten sizes bigger than the body.

“What was the scariest thing ever happened to me?” she echoes the question. “Well now. ah cain’t think right offhand—oh yes, oh yes—that time in the barn, it was mighty scary. . . .”

She was four years old then and the Tarpley family (her full name is Brenda Lee Tarpley) lived in Atlanta, Georgia. The barn stood on their land and it was so old that her father Ruben claimed it sheltered Reb soldiers in the Civil War. He also said. “You kids had better keep out of that tottering heap if you know what’s good for you.”

Brenda was a bright child understood early the meaning of the word “authority.” It was something you disobeyed. She led her two-year-older sister Linda and a bunch of playmates into the forbidden territory. Later her father found out and this time he tried explaining. “You young ones are flirting with death.” he said. “If you get in trouble I can’t come in after you. I’m a big man and if I set foot in there those rotten timbers’ll just cave in.”

Now that she understood. Brenda did it again. The kids were snooping around in the barn’s gloom one day. just about able to see each other, when they heard a sound. Not the scamper of little disturbed creatures. This was a terrible sound—a low, ghostly moan that rose in a wail till the children huddled in terror.

Then they saw it—the horrible thing moving mysteriously in the barn s murky depths! Ghostly, ghastly—five terrible outstretched white fingers attached to nothing!

“The Hand!” Brenda shrieked, and streaked out of there with the others on her heels. She ran and didn’t dare look back. If that thing could leave the TV screen from her pet horror show. “The Hand,” and come to haunt her in the barn for being naughty, it could chase her now. She made a screeching beeline for the house and never went near the barn again.

In time Brenda learned that The Hand had been her father’s, white-gloved and poked through a hole in the side of the barn. The eerie wail was his, too. “But I learned my lesson,” Brenda recalls soberly. What did she learn?

“I learned there’s no such thing as ghosts—now nothin scares me.”

And that’s just what scares her manager-guardian. Dub Albritten. He knows there isn t an awful lot of girl in a sub-size-five dress, but what there is is pure pluck and reckless daring—and this gives him silver hairs among the reddish-gold. He also knows that Brenda s father, to whom she was very close, died tragically in a construction accident when she was a little girl of seven. It seems to have left her with a rather mature and objective attitude toward death . . . but with it a shrug and an “everybody’s got to go some time feeling that gives her relaxed nerves while older heads are being lost. . . . In a plane she falls asleep soon as her safety belt is fastened. Winging to a date in Texas she slept all through the early stages of engine trouble and the growing tension aboard. When the sickening lurching finally woke her, she embarrassed poor Dub no end. Over the praying and even weeping of fellow passengers you could hear the voice of this pint-sized pixie. “Hey Dub,” she asked calmly, but loud, “we gonna crash?”

The kid had spunk

Fortunately, they didn’t. . . . The half-inch scar on Brenda’s face dates much further back — to age three. It slants at an intriguing angle from her right eyebrow to her nose, a souvenir of early childhood impetuousness. Romping in the kitchen with her sister made both of them thirsty, whereupon Brenda challenged Linda, “Race you to the sink.” She was little and fat but she got there first, made a flying leap for the faucet and missed . . . cracked her head on the spigot of a gas can next to the sink and was rushed to the doctor for seven stitches. Her mother, Grace Tarpley, remembers that they didn’t put the toddler to sleep, but she didn’t cry. Just held tight to her hand and kept asking, “Is he fru yet? Is he fru yet?”

The next year Linda, who was all of six, took her little sister to school and entered her in a talent contest. Brenda sang “Slow Poke” and won a box of peppermint sticks. She liked peppermint so much that she decided to become a singer. She grew up with perfect pitch, able to hear a tune once and pick it up, and she never learned to read music. Her father lived to see her on TV in small shows—he stayed home every Saturday to mind the baby brother Randall while Mom took Brenda to the TV studio . . . and he died convinced she was going to be somebody.

When Dub took over the reins of her career she was a veteran performer of eleven who’d held more mikes than dolls in her hands, and who never got stage fright. And he was a mild-mannered, soft-spoken guy with old-fashioned ideas about little girls.

A crazy character

That first summer of their togetherness he was sitting outside their cabana in Daytona Beach, Florida, when he saw some crazy character buzzing around the sand on a motorcycle. He called inside to Grace Tarpley, “Come on out and look at that durn fool down there. Is he mad? He’s gonna skid off that thing and scrape the hide off hisself.”

The sand was flying out from under the wheels and a dozen times the cycle was about to tip over. Dub muttered. “I swear that idiot’s gonna kill himself.”

The idiot zigzagged crazily up the beach, screeched up to them, spattering sand right and left, and somehow got off on two feet. But they were such tiny feet. Brenda’s, of course. She was grimy and sweaty and grinning like there was no tomorrow. Dub was so scared he bawled her out but good.

Try anything once

Brenda stood giving them her innocent look. When he was all through raging, she said, “But Dub, what’s all the shouting? I only wanted to try it once.”

Trying anything once—that’s big with Brenda. There was the time in Porto Allegro, Brazil, when the fans got out of hand for a change. They were jammed sardine-tight at front and rear doors. The police couldn’t clear a path. As a last resort they made a flying wedge and carried Brenda hand-to-hand over their heads to the waiting car.

No sooner were they in than hysterically screaming fans swarmed over the car, fists pummelled the closed windows. The ear rocked dangerously. White-faced. Dub leaned over to the front seat where the interpreter and the driver scrunched under the dashboard, fumbling with wires. “What are you doing?” he shouted.

The interpreter gestured towards the driver. “He says must fix siren before can go. Siren scare off crowds.”

“For Pete’s sake, tell him to forget the damn siren and get us out of here,” Dub cried desperately.

Just then the siren clicked on with a long, piercing shriek. Bodies quickly melted from the windshield, at least. The car crawled at a snail’s pace through the still chaotic crowd. The driver muttered fierce curses. The interpreter peered wild-eyed at the sea of humanity that barred their way.

Dub gripped the front seat so hard his knuckles were white. He didn’t dare look back to see how many people had been crushed. He shuddered as another hand slammed against the window. If the glass should shatter . . .

Brenda tensely clutched the top of the front seat too. A little frown creased her forehead. She licked her lips uneasily. She didn’t look at the crowds, only stared intently at the grim-faced interpreter who was frantically pumping the siren.

Poor kid, Dub thought, she must be frightened out of her mind.

“Dub?” Brenda whispered uncertainly.

“Easy, honey.”

“But Dub . . .”

“It’s gonna be all right, kid.”

“But Dub,” she pleaded, “please—will you ask the man can I come up front and try working the siren?”

Just so, through the years, Brenda has worked her way up from trying tree climbing and no-hands-bike-riding to water-skiing, tightrope walking and motorcycle drag-racing. When she limped back from her first drag race with a three-inch gash on her thigh, the pain didn’t bother her so much as what her mother would say if she found out. (“Dub, promise you won’t tell. She’d kill me if she knew.”) And if the wound left a scar, how could she explain it? It did and she did—by fibbing.

“I tole a li’l grey lie,” Brenda admits sheepishly. “I said I smacked into the edge of our new coffee table. I wonder if Mom really believed me, though. . . .”

Chances are Mrs. Tarpley didn’t. But she probably knows that you can’t reform a little rebel with a tongue-lashing. She knows that at sixteen Brenda still has to “try” things to find out what makes them tick . . . and sets her size-three feet down stubbornly as she insists, “I can take care of myself.”

So Dub chain-smokes and has trouble sleeping. But Brenda has nerves of silk over steel. Nothing fazes her. Nothing throws her—right up to the moment when she was slipped a crucial question.

“Is it true, Brenda, what a French magazine wrote—that you’re not a teenager, you’re really a thirty-two-year-old midget?”

Then did she blow up!

“Say, listen,” she said, “I don’t mind that midget part so much—but thirty-two? My gosh, do you realize a rumor like that could lose a girl all her boyfriends?”

This is Brenda Lee.

THE END

—BY ROSE PERLBERG

Brenda Lee records on the Decca label.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1961