Be Have Yourselves!

When stars get into trouble, they complain that we newspaper people have the advantage over them. We can get our side of the story into print; they can’t. This is not true. Any honest reporter would rather have the truth straight from the horse’s mouth than be forced to get the story from roundabout sources.

Last fall, just before she left for Africa, Ava Gardner had two fracases with Frank Sinatra that supplied plenty of headline material. All sorts of veiled hints were printed about the matter. Rumors, some of them lurid indeed, flew thick and fast. The public was given just enough of the news to whet its appetite. Ava was furious over some things she read. Reporters kept digging. I finally got hold of her and begged her to tell me the truth of what had happened. I even promised to let her approve the story before it was sent to the papers. But she wouldn’t give an inch other than to say, “It’s a personal matter. I don’t want to discuss it.” I explained that was no way to keep reporters out of her hair. She was hot copy. Something was certainly going to be printed about her. Why shouldn’t it be the truth?

That made no impression. “Why,” she demanded to know, “can other people get away with murder and every time I wash my hands I make a headline?” But more important than the headlines are the letters that follow.

Before me on my desk is a letter typical of those that have been flooding my office for months. It’s from a lady who lives in San Antonio, Texas. She has a problem. I dump that problem squarely on Hollywood’s doorstep. And I label it: “To Whom It May Concern.”

“I have a small daughter,” the lady writes, “and it is my intention to keep her away from motion pictures as much as possible—altogether if I can. In doing so, I know that I’m depriving her of a lot of pleasure. But how can I teach my child one set of morals at home, then let her see certain movie stars, glamorized and successful, flaunt that moral code in the face of the world—and get by with it? To impressionable youngsters it must seem that misdeeds pay off handsomely.”

The lady added that she was setting an example for her daughter by refusing to see any picture in which anybody of questionable character appeared. If you multiply her by thousands—and you can—you will understand how star indiscretions have resulted in tremendous damage to an already tottering box office. More important: How is the improper behavior of stars affecting the lives of people, particularly the youth?

Since the beginning of movies as an industry, a certain amount of justifiable criticism has been leveled at the behavior of Hollywoodites who refused to conform. But the new wave of public wrath, I believe, started with the Ingrid Bergman-Roberto Rossellini affair.

Ingrid was idolized by millions. Publicity practically built her into a saint; and she was not averse to the halo adoring fans placed around her head.

For a while she had many people fooled. They never guessed what lay beneath that cool, poised exterior. But I began to find cracks in that shining armor of Bergman’s. She had an aloofness, whether feigned or real, that startled me. She seemed to regard her fans as a sea of abstract faces to whom she owed nothing. I had more than one argument with her about this matter. But her attitude never changed. And when Ingrid openly had a love affair with Rossellini while still married to Dr. Peter Lindstrom, it was like hitting her fans a blow in the face with her fists.

The shock and disappointment were bad enough. But how many young girls and thoughtless women said, “If Ingrid Bergman does it, why can’t I?” There is where the real harm lies. Many copy the actions—good or bad—of their idols.

Ingrid is paying heavily for her impulsive behavior. She’s still the artist. But who sees her pictures?

It’s true that time has softened the bitter criticism leveled toward Ingrid during the post-Stromboli days. In Photoplay’s poll, for instance, fans voted for her to return to American films, and the ratio in her favor was three to one. And from fan mail I judge that the public is beginning to forgive Bergman, the woman; but not Ingrid Bergman, the movie star. Fans just won’t forget that she let them down and set an example that their own daughters might be encouraged to follow.

Some Hollywoodites were taking morality lightly before the public started putting its foot down. If the wrath had been heaped on these people alone, it would have been only justice. But for their actions, all Hollywood has suffered a black eye.

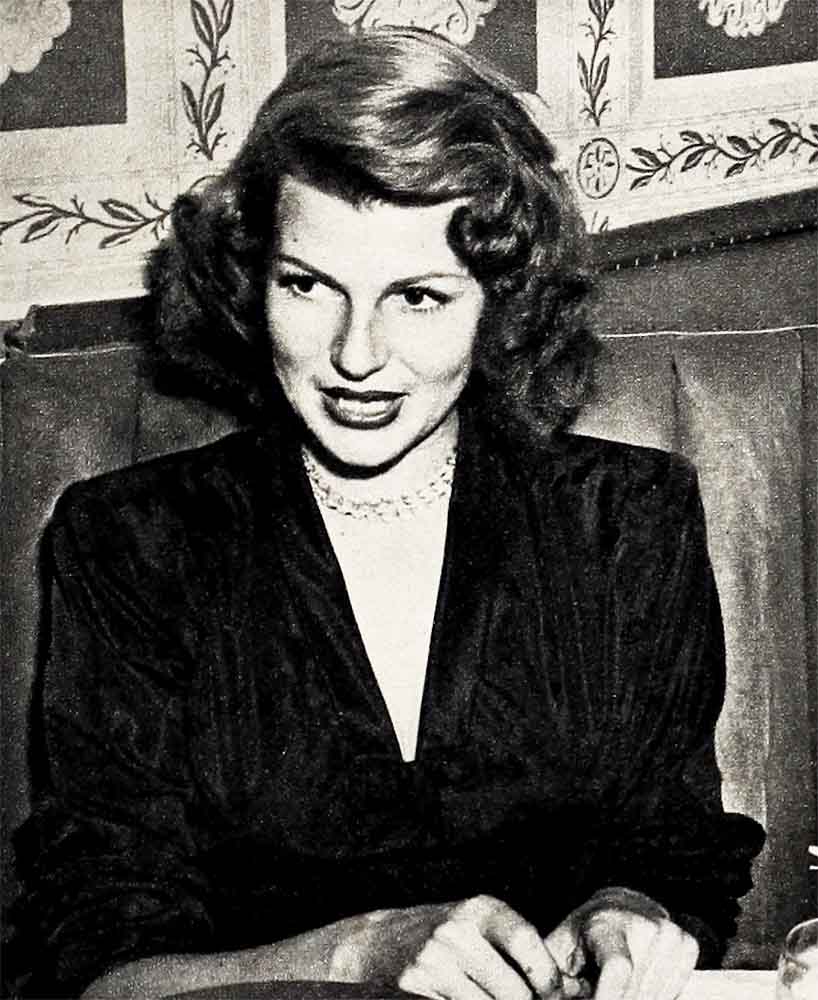

Rita Hayworth, who was making headlines with Aly Khan, is still on trial. Nobody can yet say whether the public will accept her as of old. I’m told that her picture, “Affair in Trinidad,” is earning money; but I’ll have to see a certified account of the box-office receipts before I believe it. Besides, that film is hardly indicative of the future of her career. It was her first picture since she became a princess, and, therefore, a novelty. People wanted to see how Princess Rita looked on the screen. But from now on she’s on her own with a public that has a far from completely amiable attitude toward her.

She asked for it. When she first started gallivanting over Europe with Aly Khan, Rita was single. But he was not. The whole world knew it. Frowns of disapproval began to blacken Rita’s horizon.

There’s little indication that Rita bothered her pretty head greatly about such criticism. But Hollywood, which the public seems to regard as a lump sum rather than a pattern made up of many individuals, did. The town knew that Rita was again bringing it under fire, and many upright citizens resented it.

Rita married her prince; but let it be said that she certainly never went into obscurity. Her every move was fervently chronicled by the press. To wide-eyed young girls, it was a fairy tale that came true: the poor little maid who turned into a princess. Rita had her baby; and then we began to hear rumblings that the marriage had gone sour. Cinderella came home; and Aly’s continued playboy antics further cheapened this publicized marriage.

Rita can now redeem herself with the American public only through hard work and circumspect living. But after finishing a second picture, she sauntered right back to Europe; and there she began making news again with men other than Aly. If Rita continues to ask for obscurity, I’m sure that the public will eventually oblige her. I could name a dozen youngsters who, with the proper publicity buildup, could step into her shoes. Stars are usually a bit late in getting around to this şort of news; so I’m handing it to Rita now. No star is irreplaceable.

As for Ava Gardner, I personally believe that having children would solve many of her behavior problems. She’s always wanted kids; and they would give her a sense of responsibility which her career has failed to do. I think that she’s tried to make a go of her marriages. But what chance had she as the teen-age wife of Mickey Rooney and Artie Shaw? These fellows have a habit of not wanting to stay married.

And now Frank Sinatra. This guy has a positive talent for trouble. Together, he and Ava are dynamite. Frank is a moody fellow with a hair-trigger temper, but he can charm the birds off the trees. I know of nobody who can get himself in and out of the doghouse so fast and so frequently. Frank somehow bears about him an air of innocence. Hearing his side of a story, one is apt to think: “This poor wronged boy!” I know, because I’ve been snowed under by that old routine. After a series of bad stories had broken on him, I offered Frank my column to explain himself. He did so convincingly. But before the story hit print, Frank was in the headlines again. This time he’d smacked Lee Mortimer and reaped the ire of the Hearst press empire.

To get that little matter straightened out required a bit of doing; but Frank did it. Through a friend of mine, he got in to see William Randolph Hearst himself. Evidently he turned on the charm and air of injured innocence, because the Hearst reporters promptly left off flaying Frank. But that didn’t teach Sinatra a lasting lesson. He was to have many stormy sessions with the press after that.

Nobody can tell me that bad publicity did not help a great deal in undermining Frank’s career. When he separated from Nancy, I was amazed at the number of letters I received from bobby-soxers expressing great indignation at Sinatra’s action. Frank is trying hard to pull his career together. He’s returning to Metro for one picture; and at this writing is up for the dramatic role of the embittered Italian soldier in “From Here to Eternity.” This could open up a new phase of show business for him—that of being a dramatic actor. Now if he’ll just behave himself, he might regain his old popularity.

Lana Turner is another who could do with more self-discipline—much more. She allows herself to be governed completely by her emotions rather than by her mind. She acts first and thinks second. In going back over her life, I was astounded at the number of errors she’s made. Her studio has frequently called her on the carpet. She calms down when her bosses start reading the riot act; but you never know when she’s going to erupt again. It was her bad luck to be with Ava Gardner when Ava had her last big quarrel with Frank Sinatra. Naturally Lana got her share of brickbats.

Because she was a beautiful young girl with a Cinderella story, people overlooked many of Lana’s impetuous, foolish deeds. But no more. The public expects her to act her age. So does her studio. Youth will soon be slipping away from Lana. Her career will then depend upon her ability as an actress and the esteem the public has for her. Metro is patient, but it can be ruthless when necessary.

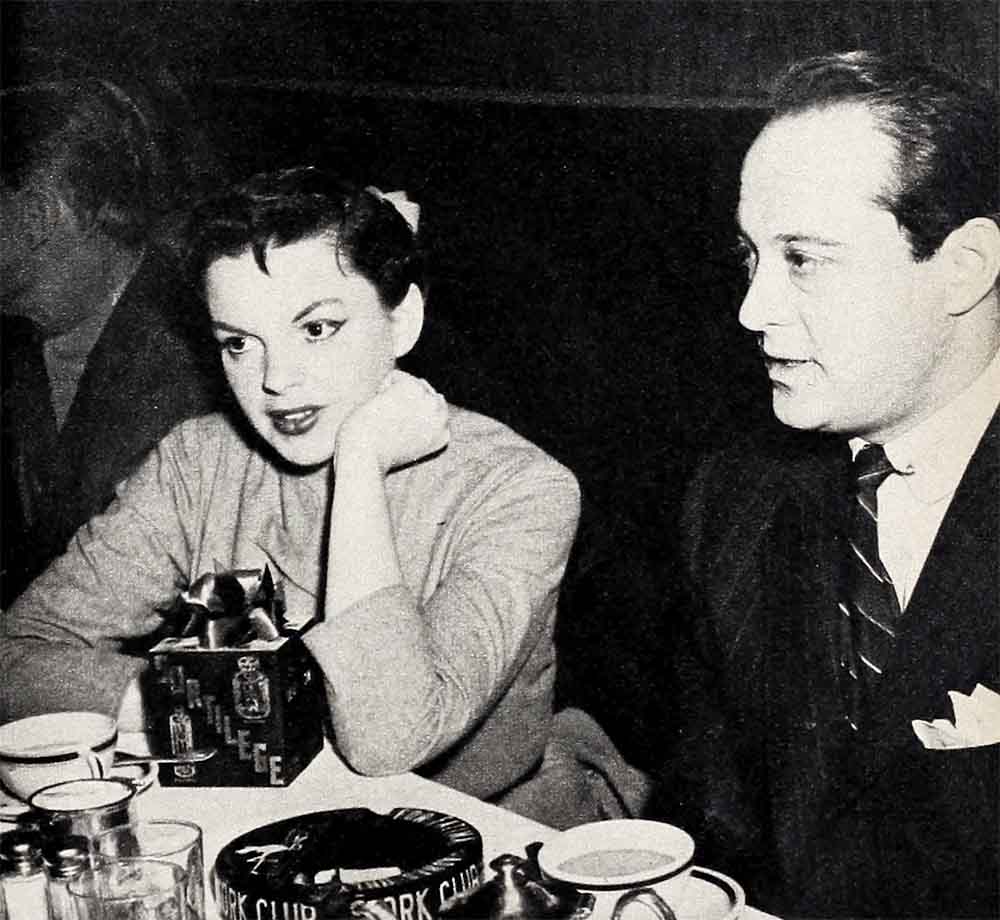

This was proved in the case of Judy Garland, one of the greatest money-makers of them all. When Judy used to scrap with her studio, I always got myself right in the middle by taking her part. I knew she was being overworked and had a diet problem. Shedding pounds before starting a picture left her nerves jangling. I’ve seen her working on a movie set when she was so exhausted she was shaking like a leaf. But still she wanted to do big pictures. When her delays started costing Metro money, Judy was dropped like a millstone. That can happen to any player.

But Judy’s case was special. Having grown up in the movie industry and into the heart of America, she was always the little girl from over the rainbow. Anything she did as an impulsive, stubborn woman reflected on that little girl. The public was profoundly shocked. But her personal appearances proved she still had a strong following. I’m wondering, though, how the public at large will take her when she attempts a screen comeback in “A Star Is Born.”

Judy and Sid are married now for better or worse. And they are doing everything to insure that her next film will be a successful one. They’ve got Harold Arlen, who wrote “over the Rainbow,” to compose the score; and Moss Hart to do the script. But if she starts slimming down for the picture—as certainly she must—she’s likely to get the old “nerves” back.

Mario Lanza leaped to stardom, then mystified his multitude of fans by brushing aside his film career, at least temporarily. When he balked at doing “The Student Prince,” many thought it was due to an enlarged head brought on by too sudden fame and fortune. I met Mario long before he made his first picture and have helped push his career. He is one of the few actors who ever thanked me publicly for the aid given him.

But when his trouble with Metro started, Mario absolutely clammed up. I couldn’t even get him on the phone. After seeing the storm warnings being hoisted at the studio, I contacted his wife, Betty, and pleaded with her to have Mario call me with his side of the story. Betty sounded slightly hysterical, but would tell me nothing to explain Mario’s action to the public. So the public was left to believe that Lanza had turned into a temperamental, spoiled brat. He did nothing to refute the reports.

I had heard that Mario was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. There’s nothing shameful about that. It could happen to any of us. “If Mario is sick, let the public know,” I told Betty. “He’ll get the sympathy.” She would admit that he “needed only a little rest,” but promised Mario would call me. He sent me flowers “with love” several months ago. Otherwise I haven’t heard a word from him. He owes the truth to his puzzled fans. Their indifference can break him as fast as their enthusiasm made him.

It was, I believe, Bob Mitchum’s complete honesty in the marijuana episode that saved his career. A married man with children, Bob had no defense for his deed. And when he took his medicine without wailing, he began to gain public sympathy. But he has learned his lesson. Now he’ll walk away from trouble. Not long ago, I saw a writer trying to needle Bob into anger. Mitchum wasn’t afraid of the fellow; but he didn’t want trouble. He sidestepped it by readily admitting that every bad thing the writer said about him was true. In so doing, Bob won the fellow as a friend. But Bob is by nature reckless. So he keeps his studio publicity department in a sweat. They never know when he may be making the headlines again. I don’t believe his career could survive a second jolt similar to the first.

Morality has moved into the political front. The Standard contract bears a clause giving a studio the right to drop a player if he does anything to damage his box-office potentiality. The last election proved that America detests Communism and its front organizations. Yet some of our players keep flirting with red ideas. I believe left-wing political activities have done more than anything else to curtail Charlie Chaplin’s career.

Sterling Hayden got sucked in by the Commies; but he got out on his own volition, reported his former party affiliation to the FBI and cooperated with investigators. His career suffered not at all. In fact, 1952 was his busiest year as an actor. Behaving oneself does not mean that a star must be forced into any set political beliefs.

The public is eager to know the facts. On my lecture tour throughout the country, the one question asked me most frequently was about Communism in Hollywood. A handful of reds associated with the movie industry in the public mind had given our town an enormous shiner.

Whenever a star gets so big and demands the “free soul” of an artist, I’m always reminded of a story told me by Florence Bates. While doing a picture, she heard a talented young girl talking rudely to a cameraman. When the scene was finished, Florence called the girl into her dressing room and told her the anecdote about the fly riding on a cart pulled by oxen. Looking back, the fly said, “My, what a dust I’ve raised!” Then Florence pointed out the work of the writer in preparing the script; the producer who had to put the picture together; the director who has to see that the scenes come off well; the men who build the sets; and the electricians who light them; the publicists who have to sell both stars and their pictures to the public. The girl then saw how infinitely small her part was in the making of a picture.

I get sick of people who revel in the gifts of stardom but groan at the liabilities. They forget that they were deliberately created in and by the public mind; and therefore, to a great extent, belong to the public. They want the fame that brings screen success; and at the same time, the anonymity of John Doe when they choose to step out of line. This is impossible; and, having written about Hollywood for many years, I’ve sweated blood in trying to explain it to stars.

If all stars would take stock of themselves, they would see just how dependent they are on their associates and the world for their success. They have no right to offend the public who decides whether or not they’ll swim or sink professionally. I for one feel the time has come for the people of Hollywood to draw the line. We must say to the stars who won’t conform: Behave yourselves, or there will be no place for you in our town.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1953