All The Things Marriage Is Made Of—Alan Ladd

They’ve written their own story of a marriage, Sue and Alan Ladd. Written it on two photographs, taken fourteen years apart. The faces in those photographs have changed with the passing of the years. But the words, and the meaning of the words, remain unchanged.

“For My Wife—from whom I will never be apart, come what may—” Alan had scrawled this on the picture of him as an Army corporal and had angled it so that a lonely Sue could read it, first thing in the morning and the last thing at night before going to bed.

Fourteen years later, a photograph on the polished piano top in the Ladds’ new, picturesque Palm Springs home bears the same, almost unintelligible scrawl—a scrawl that Sue reads with her heart: “Forever—come what may. . . .” And forever, come what may, is the heartwarming story of the Alan Ladds. It’s all the things marriage—their marriage—is made of, and all the pictures, the pages, that live between the words . . . and the years. So many pictures, so well remembered.

One picture is of the two of them leaving a studio casting office, so discouraged, and Sue breaking into tears, crying, “They’ve got to see what you can do!”

Another is of them standing, hand in hand, like excited children, that first time in New York’s Times Square, their hearts full, looking up at the marquee of the Paramount Theatre blazing out their triumph: “Starring ALAN LADD.”

There’s the day a weary-voiced Sue told Alan, “I can’t marry you.”

Then the camera of memory focuses on a hospital room, and on a white-faced Alan who hadn’t slept in three days. Three days and three nights of sitting there beside Sue, being there if she should waken, silently but fiercely willing her his strength. . . .

These, for Sue and Alan Ladd, are the things a marriage is made of—and theirs is the story of two people who have lived almost as one, who have always been so married that, as Alan has said, “Sue knows me better than I know myself. You know, sometimes it frightens me. I start to say something—and Sue says it first.”

It was that way from the beginning. Never “me,” always “we.” The screen’s new heart-throb, the romantic “gat guy” with the steely eyes and the black-velvet voice, was almost a third party to them. As Alan explained it, “Susie and I—well, we think of Alan Ladd as somebody apart. When something seems right, we say, ‘That would be very good for him.’ ”

Susie and I. There was no separating them from the start, regardless of those who might try. And there were those who did try—careless spreaders of the careless word that, for any but people like Sue and Alan, could have been the dynamite that might have blown their world to bits.

And go even farther back, if you will— go ’way back, and realize the difficulties a girl with Sue’s background might have had, trying to understand a guy with Alan’s background. A man more vain could have resented her success—and resented the occasional reminders of what she contributed to his success. Two people less in love could have been influenced by studio brass, who predicted marriage would mean the death of Alan’s career. And their years together, living and working almost as one, could have strangled another marriage, less strong.

Pretty brown-eyed Sue Carol was the only daughter of a wealthy Chicago realtor. Her life had been filled with finishing schools and summer vacations in California and Switzerland. Without even caring too much, she’d become a successful star-ingenue in movies. But Sue has said of this: “Alan’s career has always meant a lot more to me than mine ever did. I was just out there—and somebody said I was the type.” Later, she became a successful agent, with plush offices on the Sunset Strip. Everywhere she turned she found herself touched by success.

For Alan, life had been hard and hungry. He was a graduate of the school of hard knocks, and he had the scars to prove it. Leaving his Arkansas birthplace when he was eight, he had migrated west with his mother and stepfather—an unemployed painter—in a wheezing jalopy that broke down all along the way. Alan scrounged around, learning what he could, when and how he could. But nothing could kill his restless desire to be somebody, to belong somewhere, to find his place in life and prove he belonged there. As a shield against disappointment and discouragement, he developed a toughness that could hide the hunger inside him—but not the hope.

He picked apricots and he fried hamburgers at drive-ins. He worked as a grip at Warner Brothers, rigging scaffolding high up on the sound stages, to light the magic of which, someday, he silently vowed, he would be a part. He struggled for five years to be an actor. By the time he met Sue, his silky, deep voice had opened the door for him in radio. CBS wanted to talk to him about signing with them. But the break he wanted in pictures would never come for him, he was sure, the day he opened one more door and walked into another life.

Nor had Sue Carol known exactly what to expect that day. She had been intrigued by the performance of an unknown actor on a radio show, and she had phoned, asking him to come see her. But, she thought as she waited, he was probably paunchy, with thinning hair.

Remembering now, the fellow in the blue sport shirt and white sweater and his pretty Sue, so chic in pink, look at each other in their Palm Springs living room and grin.

“Alan was wearing a long white polo coat,” Sue recalls. “He was very tan and blond and handsome—and he said he wasn’t in pictures! I couldn’t see why.”

“Why don’t you let the public decide?” Sue had asked him then. As far as he was concerned, Alan said, Hollywood had already decided. And he knew he could work in radio.

But the next day, driving along the Sunset Strip to keep his CBS appointment, Alan had stopped at Sue’s office and gone in. “I walked into her office to tell Sue I wasn’t going to sign with her. I’d had no intention of signing when I said, ‘Where’s your contract?’ I don’t know why I signed,” Alan says now. But then, he always had an instinctive heart and a quick, experienced eye. That much, at least, life had given him.

But nothing about his life had ever prepared him for faith and understanding like Sue’s. From the very beginning, she fought with all her heart and know-how, determined to get him his chance. As she explains now, “Alan was always so much more appreciative than the other people our agency had—and for the smallest thing you could get for him, an interview, a bit part, anything.”

And the public, which was to be the final judge?

“The public had no choice,” Alan smiles now. “Susie just wouldn’t give up. No matter what a studio casting director wanted, I was always ‘just the type.’ They’d ask her if I could sing and dance—and Sue would just blink those big brown eyes and say, ‘Yes, he can!’ ”

“But the funny thing was,” says Sue, “Alan really could sing. They just wouldn’t give him the chance. Alan’s voice has a terrific quality. He would be great in musicals now.”

Yes, in Sue’s opinion he could—he can—do anything. And he frequently did.

“I was a ski instructor in a movie at 20th Century-Fox,” Alan recalls, “and I would spend all day putting on my skis and going up and down. About the same time, Sue got me an interview for a commercial film. It was for an insurance company and they wanted somebody to age from 18 to 80. She told them I was just the type.

“That night when I was through skiing, I went over to see them. They sat me down in a chair. They pushed my face p and wrinkled it and put on spirit gum. Then they yanked the gum off, leaving the ‘wrinkles’ there. One guy stood back and asked the other, ‘Well, what do you think?’ Then they did the whole bit again, putting on the spirit gum and yanking it off until my face felt like raw hamburger. But I got the part. I’d work nights there until 3:00 am., get three hours’ sleep, and be back on my skis again over at Fox.

“I went to Chicago for another commercial film,” Alan continues. “I got $500 a week and I got to wear a dinner jacket and carve a turkey. It was fine experience—and I learned how to carve.”

But there were other, leaner weeks during those first few years, when there wasn’t any turkey. Days when it seemed as if all the faith and talent combined—all their teamwork—wasn’t going to get Alan his chance.

“When we least expect it, a part will jump up,” Sue assured Alan then. “You’ll see.” It was always darkest before dawn, she told him, running through all the comforting bromides used to bolster battered spirits and egos. But leaving a studio one day, Sue burst into tears, feeling she was failing Alan. “We’d missed quite a few jobs then,” she recalls. “And that day Alan snapped me out of it.”

And finally, sure enough, the dawn they’d waited for came. After some seventy bit parts on the screen, Alan gave a performance in “Joan of Paris” at RKO that led to a test for the part of the cool-triggered, cat-loving killer, Raven, in “This Gun for Hire.” The part that would make Alan Ladd a star.

After this one picture, Alan was the fans’ idol and Hollywood’s heralded new star. With security in sight, he asked Sue to marry him. “I guess I fell in love with Sue that first day I walked into her office. I saw her—and that was it. When two people click,” Alan says simply, “that’s it.”

Then a shocked Alan heard Sue say she couldn’t marry him. Unknown to Alan, studio executives had gone to Sue with long faces and said marriage would endanger Alan’s whole future—the future Sue had fought so hard for. When Alan found this out, he went to the studio brass and blew his top, reminding them Sue was the reason he even had a career, and adding pointedly that, unless he married her, there would be no career.

They were married twice—the first time while Alan was on location in Mexico. “But you don’t feel very married in Mexico.” So they had a religious ceremony in Santa Ana later on, “a very sweet marriage, with just a few close friends there.” And Dixie and Bing Crosby loaned them their Rancho Santa Fe home for their honeymoon.

They lived in Sue’s comfortable old brick home in the older section of Hollywood, until Alan could build the elegant house he planned to give her. And from the beginning they proved the studio economists wrong. The fans took both Ladds to heart, loving Sue all the more, because she was so important to Alan.

It took World War II to separate them. Alan enlisted three months before their first-born, Alana, arrived. He was the hottest property in Hollywood, king of the box office, and leading every fan poll. He’d starved and struggled all his life to be somebody, and some professional mourners were quick to say, “Kid, nobody will remember you. You’ll have to start all over again.”

The brick house waited for him, the way you can feel a house waiting for a man to come home. And the house began to breathe again when a bronzed figure in khaki came through the door, clutching Sue in one arm and his first three-day pass in the other.

Marriage, for Alan, too, other war-time memories.

“Like Susie coming up to Walla Walla, Washington, when I was stationed at the B-17 base there. She took a little room in a hotel. One night when I got back from the base, Susie had gone to the dime store and picked up a tall vase, and a little pot she planted with Philodendron— things like that. She soon made it home.

“One of the sergeants’ wives had an apartment, and Sue would go over there and prepare the food,” Alan goes on. “She used to gather up all the meat ration points and make a picnic in the park for a lot of guys from the base and their wives. I was getting $68.50 a month. We were running a house in town, we had Carol Lee, Laddie and Alana to care for, and I thought I was going overseas any minute. Nobody knew what would happen—and I don’t think ham sandwiches and potato salad ever tasted as good.”

As it happened, instead of going to Guadalcanal with a film unit, Alan was assigned to the Motion Picture Unit in Hollywood. When he was discharged, he still led all the stars in fan mail. Although Sue had stopped representing him as an agent when they were married, they continued as a team in any thinking about Alan’s future.

To any who have implied Sue dominated his motion-picture career, Alan has always said, “Sue’s influence has always been that of a wife, a sweetheart, and a best friend. I’ve always had the greatest respect for her opinion. She knows the business and she’s wonderful to talk to. We weigh decisions, thrash things out.”

They strengthen and complement each other. Alan’s the impulsive one, the hot-idea man who’s always making with the plans, while Sue usually handles the paper work and tries to make the pieces fit. “We’re both impulsive,” she smiles. “I just say, ‘Let’s think about it first.’ ”

“Sue’s more practical—except with me,” says Alan. “I may get hair-brained ideas and she’ll go along with me. But one thing I’ll say about Susie, when I get it all fouled up and get in a corner, she’ll pull me out of it.”

“That’s one thing we argue about,” adds Sue. “Alan has such terrific ideas, and I’m always saying, ‘It can’t be done.’ And he’s usually right—it can.”

Sue has often given Alan the confidence he’s had to have, the faith his life had denied him. She is calmer by temperament than Alan, who goes from ’way up to ditch-down. She often just voices what Alan wants done, saving him the lengthy telephoning he dislikes and all the more boring details.

As Sue says, “Alan frets about little things, but if something big comes up he’s wonderful. In a crisis, Alan’s always so calm and collected.”

Not, however in one crisis. Not during those three nightmare days and nights when doctors thought Sue wouldn’t pull through. “When all I could do was sit in the corner of Susie’s room feeling so helpless, just staring into space,” Alan says slowly now.

Complications had developed during pregnancy, and during those critical hours, one of the hospital staff informed Alan that they might not only lose the baby, “but sometimes we lose the mother, too.” A shocked Alan looked at Sue, and he could tell by her eyes she had heard. White-lipped with anger and with his own fear, Alan’s last words as they wheeled Sue to the delivery room were in the grim low steely voice usually reserved for the screen. “Bring her back, hear?”

They brought her back, along with a healthy, lusty-lunged son, David Alan. And his father began building the elegant French Normandie house in Holmby Hills that he’d been building in his mind for Sue ever since they were married. Alan haunted the place, making an eager hand for the carpenters. And at night many times, he and Sue would take flashlights and make the rounds, watching their house grow.

But as an equally impulsive Fate timed it, he was also soon buying a ranch, and taking the Ladds really outdoors—’way out. “I went to a ranch to help a friend move a piece of furniture into a caretaker’s house. I looked across the valley and loved it, and we bought the place twenty minutes later.”

And so Sue, who cared little about ranches or roughing it, was soon pioneering. There was only a lean-to and a garage on the property, and as usual Alan had long-range plans to be executed immediately.

“Sue, let’s make a room out of one of the stalls in the garage,” he suggested.

“Don’t be foolish, Alan. We couldn’t do that,” she said, even as she began bunking there.

“And we can make a kitchen out of the porch,” Alan continued.

“It just won’t work,” said Sue, who admittedly is less talented for visualizing the impossible, before it’s accomplished

Alan kept inching more space for more rooms until Sue had said, “Now where will we put the car? Don’t tell me—in the barn.” Which they did.

“One thing about our marriage, never been dull!” Sue laughs now.

For example, says Alan, “Some years later, we’re in Palm Springs. I’m getting a hamburger in the drugstore and Sue’s over looking at some magazines. It’s a pretty day, the sun’s shining, the air’s full of sparkle, and I’m asking the waitress, ‘Any property available in the vicinity?’ ”

“The best real estate man in town’s sitting next to you,” the waitress said.

They looked at three houses, and Alan fell in love with the third one. A picturesque pink and charcoal modern that wanders around in a relaxed way, and with glass walls. “I made a deposit at a much smaller figure than they wanted, never really dreaming we’d get it.” That is, not until he noticed the house number was 323, the same as their house in town. “Sue, look! We’ll get the house,” he said confidently.

And they did. “Now all we need is two more bedrooms,” Alan said thoughtfully “Who’s the builder of this property?” he asked the real estate man. “I’d like to talk to him.”

The builder, Bob Higgins, a tall redheaded Irishman with a warm smile, had gone to school with Alan at North Hollywood High. Bringing each other up to date, Higgins said he’d always wanted to build houses, and Alan said, with a familiar glint in his eye, “I’ve thought I’d like to be in the hardware business.”

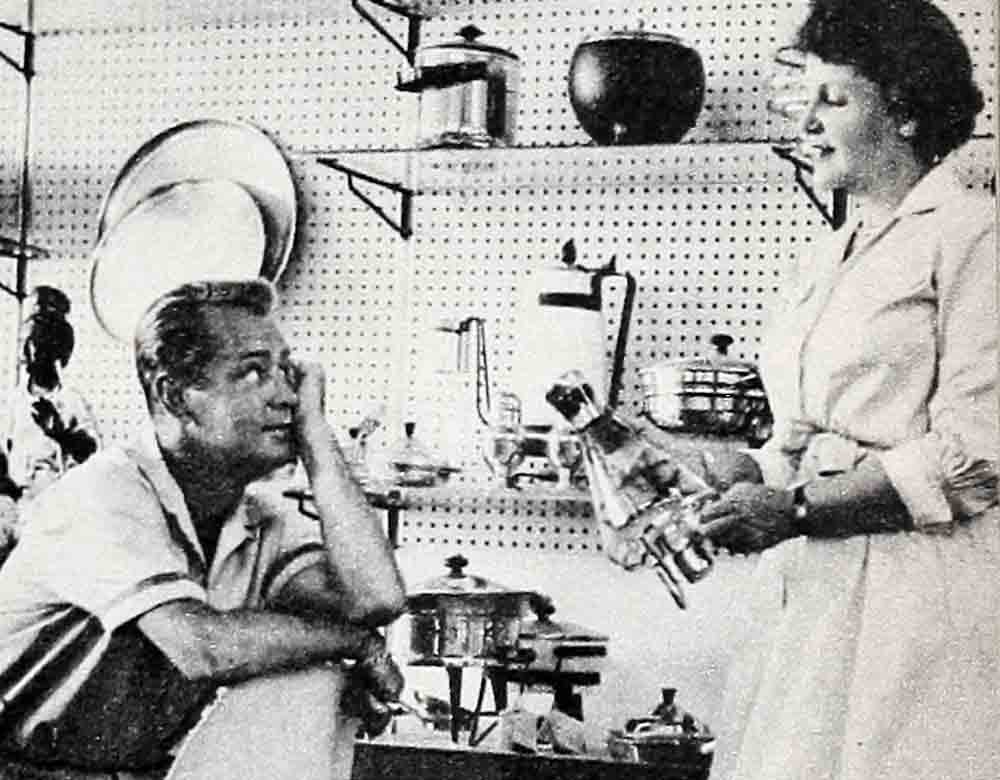

And so, before long they were partners in The Higgins—Ladd Hardware, building a jewel of a modern store on Palm Springs’ main street. They have a vast trade with builders throughout the flourishing desert area, and their many star-customers include Gregory Peck, Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra and Clark Gable. Sue personally supervises and does the buying for their imported toys department and explores wholesale houses for the smartest lines of dishes and glassware. Alan’s department? “Guns, I guess. I ordered them and set up the department. And tools—I’ve always gone for them.”

This latest venture, based like all their ventures on the solid bedrock of their marriage, is already a great success.

Continued success, however, has in no way changed the rhythm of their life together. Alan has always made Sue feel her importance in his life. “In any crowd, wherever we are,” Sue says fondly, “Alan always makes me feel like the most important gal in the room. And he always tries to make me feel important to his business, that my opinion means so much to him.”

Not that they always agree—far from it. “We both have strong wills,” Sue says frankly, “but we thrash things out. Sometimes I’ll convince Alan; sometimes he’ll convince me.”

If you ask them to name the most important attribute in making theirs a strong marriage, Sue says, “Companionship—being considerate of each other.” “Honesty,” says Alan. “Sometimes we hurt each other, and we’ve gotten hurt. But at least we’re honest with each other.”

Sometimes, like newlyweds, they’ll sit and talk the sun up, planning for the future of their family—Carol Lee, who works for their own Jaguar Productions; Laddie, a fine-looking husky freshman at USC; Alana, 13; and David, a very busy 9.

Like any parents, Alan and Sue have their own individual views on how to raise their family. Sue believes Alan is inclined to be too strict, while Alan is equally convinced that Susie’s a soft touch “and just too lenient with them.”

“I don’t think I’m too lenient,” counters Sue. “We make them earn their allowances, and I don’t think that spoils them. Laddie gets fifteen dollars a week, but he has to buy his lunches and gasoline out of that, and he has to earn it by weeding the hill and property around our house in town. Alana, who gets two dollars a week, keeps her own room in order.”

Alan makes “the rounds of the house every evening” and hears all the problems of the family, but their daughters are Sue’s department, generally speaking. Alan admittedly isn’t too effective in dealing with the girls’ problems. As he said to Sue recently, “You know, I think I’m scared of girls. I just don’t know how to talk to them.”

One evening recently, Alan and Sue were running a movie at home for the family. Thirteen-year-old Alana had invited a boyfriend over and during the course of the picture, Alan saw the boy put his arm around her. He left the room and called out to Sue in a loud voice to accompany him. He was white and shaken.

“Did you see that?” he thundered.

“Yes, I did. But it’s better that it happens here at home,” Sue said, trying to calm him. “Now don’t you say anything.”

They went back inside and Alan tried not to say anything. But, noting the boy’s arm remained around his daughter, Alan finally could stand it no longer. “Are you enjoying the picture?” he asked Alana pointedly.

“Yes, Daddy,” she sighed happily.

Across the room, Sue smiled at her husband with the ancient wisdom of women, and Alan understood—or thought he did. And later, walking across the moonlight-covered grounds of the house that love built, Alan’s hand found Sue’s and held it hard. They spoke no words—there were no words to say except the ones they’d repeated so often: “I love you.”

The struggling young actor had said it . . . the lonely corporal had written it . . . the desperately worried young husband seated beside his wife’s hospital bed had prayed it . . . and the successful producer, Warners’ top box-office draw named Alan Ladd, said it, too, on that night when they knew, as always, that marriage—their marriage—is forever.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956