Average Score: Terrific!—William Holden

Bill Holden has so often been called colorless,.unromantic, stuffy, dull or bad copy that the public has begun to wonder: “Who and what is Golden Boy Holden? Can the color, vitality and deep sensitivity he shows on the screen be just good acting? Is he a machine turning on emotions, humor and personality only for the benefit of the camera?” The answer is uh-uh—not on your CinemaScope tintype!

It takes a combination of Sherlock Holmes and Sgt. Joe Friday to tear through the facade that Bill has built around his family and himself. He answers questions honestly—but incompletely, telling only superficial facts about himself. He states his reasons frankly: “What the public expects is sometimes what the actor considers an invasion of privacy. I owe my success to guys like Billy Wilder [the producer-director], who polished ‘Sunset Boulevard’ and ‘Stalag 17’ like jewels and then got the best out of me. Popularity is due to good pictures. Is there such a thing as loyalty on the part of fans when a bad picture comes along? If your fans decide you’re just like them—which they don’t want you to be—you’ve had it.”

But Bill has nothing to worry about on this score. He definitely isn’t just the guy next door. (He points out, “The guy next door can be a jerk.”) Ardis, his wife, says, “The only predictable thing about Bill is his general unpredictability—in an interesting and exciting sort of way. He has a delightful individuality, which makes him sometimes inconsistent, sometimes headstrong. He has learned diplomacy the hard way, and his temper is usually under control now, but it can explode like a volcano. Little things get on his nerves. He has no patience with someone who fluffs a special job, and that includes himself. In our almost fourteen years of marriage Bill has matured amazingly.”

He takes his responsibility as a citizen and an actor seriously. He has accepted positions in the Los Angeles County Recreation and Park Commission, the Coliseum Board and Screen Actors’ Guild, and he works hard in all of them. Bill’s integrity would not allow him to take an honorary post. He is a champion of his fellow actors, saying, “To err is human, and stars are members of the human race. But if an actor makes a bad bed, he has to lie on the wrinkles.”

Holden and “solid citizen” and “pro” are synonymous. He is considered courteous, never gushes, likes meeting people and is good at ad-libbing. He is in the top ten at the boxoffice. His career has been planned carefully, but acting has not used up all his business sense. Along with personal property, he owns 160 oil acres in Illinois, more in Texas, blue-chip stock in Paramount, Standard Oil, Allied Artists and 20th Century-Fox. He is vice-president of his father’s chemical-manufacturing concern; he is on the board of a Dallas radio station; he is the very new owner of his own company, Toluca Picture Productions.

Holden is natural, unaffected, never embarrassed. His aptitude as a parent was learned at the knees of his very fine mother and father. Now, to his despair, they think they were too harsh and want to soften his discipline of his own children. Mr. and Mrs. Beedle (Bill’s real surname) live close by and are a part of the family life. Thursday evenings are always spent at their home when the Holdens are in town. If Bill is away, Ardis goes. Bill and Ardis enjoy each other. As husband and friend he is the epitome of all woman devoutly hopes for. All these things are Bill Holden—solid, ‘way above average, exemplary.

But the human pendulum must swing and swinging go to the other side of any man. Granted, Bill’s other side is not lurid, lusty or exotic. However, it allows the solid citizen to exist with stability. Under Holden’s calm and poise is a pacer, an impulsive, generous, sentimental, high-tempered, impatient, daredevil pessimist and optimist. Things happen to Holden—or Holden happens to things. Like this . . . One day, Bill left his home with Hugh McMullen, a long-time friend. The phone started ringing, and Bill went back to answer it. As he said “hello,” one of those California earthquakes suddenly shook the house—and Bill. Clutching the phone to his chest, he quavered, “Good Lord, Hugh, I’m having a heart attack!”

Hugh knew his man and with sly and honest humor remarked, “The application of any phenomenon, even an earthquake, to his own person is a trick peculiar to the artist.” Artist that he is, proud of his profession, Bill took the thrust good-naturedly.

He’s usually able to appreciate a joke on himself, as on the evening when he and Ardis went to see one of his movies. They were pushed and shoved and diddled out of line until Bill turned a bright red and roared, “I’ll complain to the manager!” Ardis tried to placate him, but he would have none of it. Turning to a breathing tuxedo, he barked, “Who’s the manager?”

The tuxedo answered politely, “Mr. McConnell.” After an enraged search, Bill found the manager’s office and stomped in. The tuxedo and Mr. McConnell were one and the same. “I’m the manager,” he said.

Bill stared blankly for a minute and then snapped, “Mr. Holden, my name is McConnell and I want to tell you that—”

The manager interrupted him, still politely. “No, no, my name is McConnell. Yours is Holden.” That took all the fight out of the fighting Holden.

And he’s willing to tell a joke on himself, too. As guest speaker at the Friars Club, he regaled the members with this story of a flight to Washington. Bill was traveling with Leon Ames, the well-known character actor. As a stewardess approached with coffee, Bill said, “She’s going to dump that in my lap.” Leon protested that the hunch was superstitious poppycock. Naturally, the plane lurched and Bill got the coffee in his lap.

The story drew a laugh from the Friars. Just then, a waiter passing behind the speaker tripped, and there was Bill Holden wearing the latest thing in allover chocolate sundaes. At least, he consoled himself, the waiter’s timing was perfect. It would take more than that to upset Bill’s composure as a public speaker.

He’s also a very good impersonator—once a year. When the Paramount Christmas party rolls around, he loses his reserve and does hilariously funny imitations of everyone on the lot. But it’s affectionate ridicule. At a press party in New York, Holden heard a woman blasting Hollywood with a verbal barrage. He approached her and said quietly, “Madam, you don’t know what you’re talking about.” That shut her up for the evening.

At a cocktail party in Havana, Bill took more drastic means to stop an unpleasant trend of conversation. He’d been staring gloomily out the window toward the ground, several stories below. Suddenly, he lunged out and stood on his hands on the outside ledge. This changed the subject! Furthermore, it took Ardis quite a while to get him to come back in and stand on his feet. Physical exertion has always been an outlet for his anger. In the heat of a discussion, he has been known to pick up a cane and start jumping over it forward and backward.

If his co-players in “The Country Girl” had known him better, they wouldn’t have been so startled after he fluffed his lines in a tense dramatic scene. Bill’s reaction to his own fluff was to begin methodically jumping up and down on the floor. He then jumped to a chair, from the chair to a table, from the table to a bed. Quietly and furiously he jumped up and down on the yielding bedsprings until, with one last magnificent leap, he cleared the set and disappeared completely.

Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly watched his exit with openmouthed awe. But director-writer George Seaton turned casually to the cameraman and said drily, “Did you pan in and get all that?” George knows Bill Holden.

So, of course, does Ardis Holden. She had her first warning when she was a successful actress known as Brenda Marshall and Bill was courting her. He told his intended bride: “There may be times when you don’t know whether to kiss me or crown me. But, no matter what, I don’t think our marriage will be dull.”

That was the understatement of 1941. As Ardis says, “It’s been a ball.” They were both working when they decided to get married. Knowing they were in for a long separation if they didn’t marry right away, Bill chartered a plane for Las Vegas one Saturday night. And the bridal party was under way: Brian and Marjorie Donlevy, Bill, Ardis and the pilot.

The Vegas field was closed, so they landed on an Army air strip that hadn’t been cemented. Walking in the dirt a mile and a half to the air terminal, they found it closed. Bill finally got a cab to come out and take them to town. The open-all-night office for marriage licenses was still open at 2 a.m., but the girl was out having a bite. They chased her all over Vegas, found her and got the license. The Congregational Church, where they had made arrangements to be married at midnight, was closed. They found the pastor at the hotel, but the bridal suite had been given to someone else. Bill and Ardis were finally married at the foot of a double bed in a single room by a one-armed minister who turned the pages of the Bible with his chin.

Ardis left that day for location in Ontario, Canada. Three and a half weeks later she returned, expecting to be carried over the threshold at last. But her bridegroom had departed hours before for location in Carson City, Nevada. A few days later, Bill came back suddenly—to the hospital, with a violent attack of appendicitis. On the ninth day of his convalescence, while Ardis was making one of her visits, she complained of same pains, same place. Bill pooh-poohed the thought with “You’re having sympathetic pains.” He jokingly suggested to the doctor that she should have an examination. The doctor took Ardis into the next room, examined her and came back. He suggested that Bill get up and give Ardis his bed. She, too, was scheduled for an appendectomy.

Two and a half months after that fateful wedding in July, Bill and Ardis finally looked across the breakfast table at each other as man and wife, thankful that they hadn’t waited to marry because they would have been separated. The blending of two strong personalities was on. Bill took naturally to being a father to Ardis’ little girl by her former marriage. Virginia, called Deedee, took naturally to being a daughter to Bill. Before the honeymoon was over, war was declared and Bill enlisted, in April of 1942. During the period he spent in AAF officers’ training and for the remainder of the war, Bill did his duty and kept quiet. He came home to see his first-born son, Peter Westfield. He took one look and said, “Honey, he looks like an ugly Wally Beery.” Returning to camp, Bill felt an increasing urge for freedom.

When he got home, he had too much freedom. Although under contract, he wasn’t used for eleven months, and he became a brooding, unhappy man. Ardis finally went back to work when Bill despondently admitted that he was artistically and financially busted. This was the only rough period in Bill’s career. Then along came a picture offer, “Dear Ruth.” It was a smash, and Holden was golden again.

That rough period helped to shape the Holdens’ marriage. Bill is the dominating force, but Ardis has a definite personality. She is outspoken, capable of error and the first to admit it, and sometimes tells the truth even when it galls. But she can also take it and loves someone to stand up to her. In Bill she found the one to do it.

By then, little Scott Porter had joined the family, and Ardis made her decision: “If you aren’t with your children in the formative years, you really suffer a great emotional loss.” She gave up her career and concentrated her talent on reading scripts and feeding Bill his lines (he has a great respect for her ability and would like to do a picture with her).

Together they take the character in Bill’s script and breathe life into it. What was the character’s childhood? What are his likes? Dislikes? How would he react to certain situations? Sometimes the stimulating soirees go on until dawn. When they finish, the character Bill portrays is fully alive.

At first, Bill was stuck with what he calls “Smilin’ Jim” parts. “You can’t travel,” he says, “if your vehicle is a jalopy. ” But with “Sunset Boulevard” the jaunty juvenile began to disappear. In “Stalag 17” he lowered his voice to fit the role, and suddenly the public recognized the depth, maturity and strength of his acting and pushed “Smilin’ Jim” into oblivion forever.

Before this recognition came, Ardis and Bill found their home in San Fernando Valley. It is a lovely 18th century English country home on a quiet street. Of the three bedroom suites upstairs, the boys have the largest, Deedee has her bedroom and bath, and Bill and Ardis took the end rooms so they could convert a second-story sun porch into a large dressing room. Downstairs, a big living room and a smaller den are obviously the rooms where the entire family really lives. Bill had a high-fidelity system piped in for his records long before it became popular. The pool and the cabana are the meeting place for the neighborhood kids.

Bill and Ardis seldom go out. They enjoy family life and having friends in. They love to entertain small groups of friends. Bill mixes the before-dinner drink. A connoisseur of wines, he serves the wine with dinner. Quite often the meal will be buffet with no evidence of servants. The children are well behaved and affectionate, and come in for a “good night” all around before taking off for bed. At parties, Bill and Ardis believe in good conversation rather than games. He’s an excellent story teller. He has traveled so much he is never at a loss for a fascinating story.

They are good parents. Ardis watched Scott eat his heart out at seven because he was too young to be a Cub Scout like West. Finally, she decided to take on the rugged duties of a Den mother so that Scott, being there, could be a part of it. (Most Den mothers will shudder in sympathy at this expression of mother love.)

Deedee is much too old for the juvenile antics of her brothers. One night, this teenager didn’t return home from a party at the exact hour specified. Bill started to pace. Finally, he worked himself into a frenzy of anxiety. It was Ardis who calmed him, absolutely refusing to let him call the police and the hospitals. Bill was the perfect picture of the father realizing for the first time that broken arms and Girl Scout trips were things of the past. His little girl was growing up.

Scott and West share a lusty sense of humor and on occasion can take the old man. One day Bill was doing guard duty at the pool (unless someone else is present, no member of the family swims).

Holden had a date in town later, so he hadn’t changed to trunks. Fully dressed, he watched the kids (including the neighborhood gang) frolic in the water. West took to the board and did a jackknife. He broke the water cleanly, with was scarcely a ripple. Suddenly Bill realized that there was still no ripple. West had not come up. Bill leaped to his feet and dived, fully clothed, into the pool. He found West clinging to the side of an underwater outlet, grinning like a young ape. When they hit the surface the kids were doubled up yakking at the sucker, now thoroughly wet and red-faced.

But the household is normally more peaceful. Evenings start with a late dinner (Bill seldom gets home before seven). Then he and Ardis go to the den and put on some good music. He sinks into his favorite leather chair, and they talk. They have never tired of talking to one another. Bill discusses his day at the studio; Ardis gets in the trials of being mother to two Cub Scouts and one teenager.

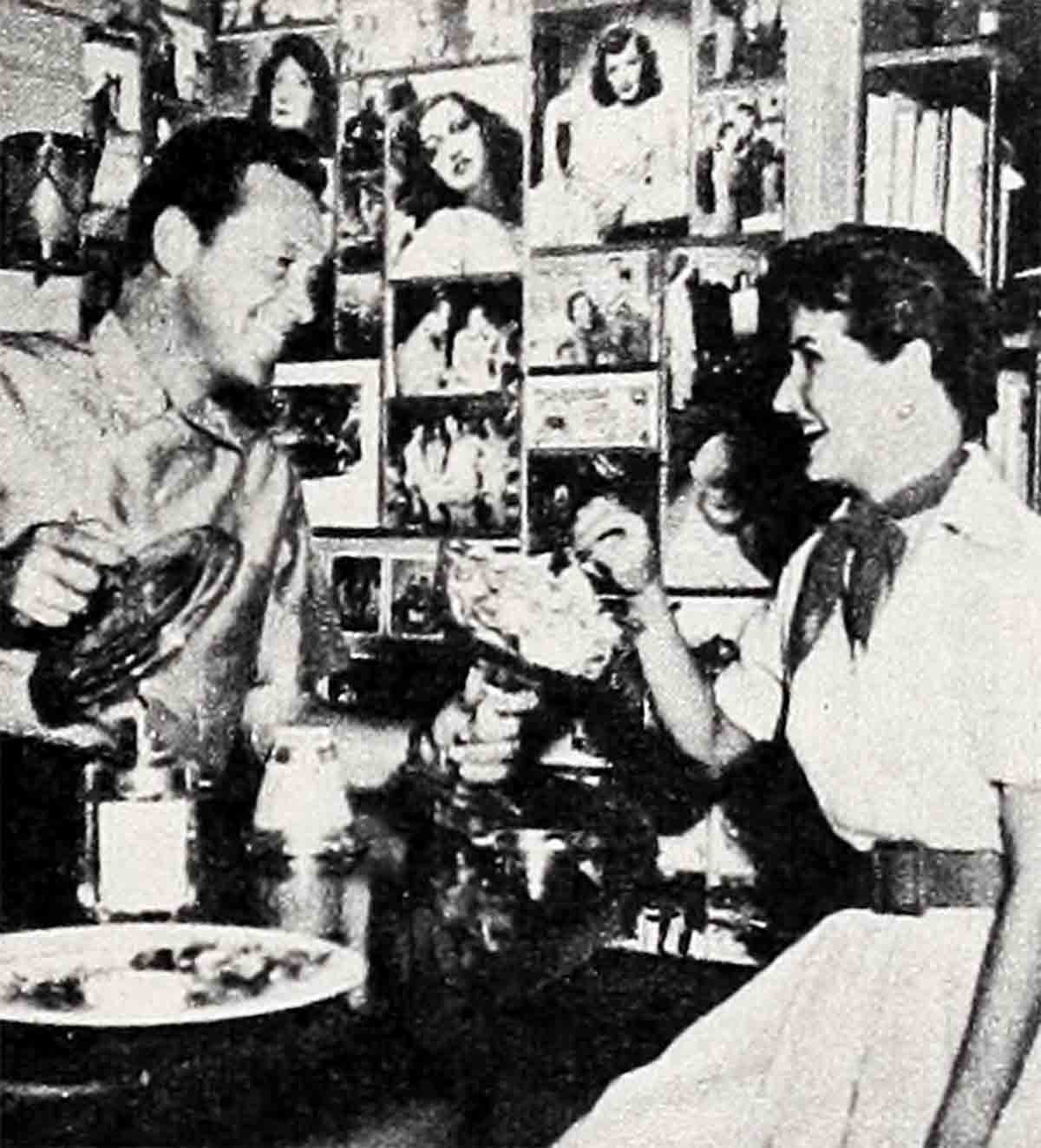

About Saturday nights, Ardis feels like a small-town girl: She likes to be taken out. They go to a favorite restaurant in the Valley, then visit friends, go to a movie or, when she can induce Bill, do a little dancing. Sunday is their lazy day. They sleep late, breakfast on Eggs Benedict or Oysters Rockefeller, read the paper, discuss the novel they’re reading together, play with the kids. The afternoons are spent poolside, with the kids. They enjoy a barbecue outside to round off the day. (Bill is an excellent cook; he holds forth with the charcoal and garlic.)

The children are expected to earn their allowances. West cleans out the pool. Scott keeps the patio and grounds policed up. Bill feels strongly about boys learning to earn and share.

The boys share their father’s spirit of adventure a little too enthusiastically. One day, when West was five and Scott not quite three, Ardis looked up from her work to realize that the sudden quiet was ominous. The boys had disappeared. She called and finally ran outside. They answered her from the rooftop, thirty feet above the concrete driveway. They were fixing the television aerial, like—Daddy!

Ardis never calls Bill at the studio unless calamity has taken over: i.e., West’s broken leg, Scott’s broken arm, Deedee’s serious burns. But the day the man came to install the television set, Ardis decided to call and get instructions from Bill. He answered the phone call with, “Who broke what?”

Ardis used to buy clothes for Bill, but he politely and firmly returned everything except a maroon robe that was so tailored it looked like an overcoat. Now she orders clothes put aside for him, and he runs out on his lunch hour to buy or not to buy. He has discriminating taste. One night Ardis added a pin to her costume, which already included earrings and necklace. Barely glancing up from the book he was reading, Bill murmured, “It’s too much, Ardis.”

Few poker-playing husbands want to break their wives in on the game. Bill’s an exception. After the war, poker was the only card game he enjoyed, and Ardis used to sit in the living room with the other wives, listening to the din in the den. She decided she’d like to join the fun—and Bill was delighted. Bill loves to share with Ardis—even his wanderlust. With the kids, they’ve made two extensive trips to Mexico. And he dreams of taking the whole family to Europe for a real holiday.

When Bill got over the restlessness and tension caused by his career problem, itching feet and insatiable curiosity took their place. He wanted to know everything about the rest of the world. Paul Clemens (the artist recently married to Eleanor Parker) says, “Bill is the dream listener for a returned tourist. When I returned from a three-month Caribbean tour, Bill listened avidly, devouring my experiences. Later, when I returned from France, he was ready to listen and absorb again. Because he planned to go everywhere, he wanted all the second-hand information he could get.”

Bill has a huge world map in his dressing-room office. When he’s going to travel, he reads about the place, its history and future in great gulps. He keeps digging and rooting around, wangling letters of introduction so he can reach unusual, out-of-the-way places and people. Because his taste is elastic, he can enjoy all cultures.

Wherever he goes, he buys for everyone: producers, secretaries, grips, Ardis, the kids (and himself). After his Far East trip, he gave producer Irving Asher an intricate and lovely Chinese cigarette holder for his desk. Atop the holder, a coolie carries the conventional stick across his shoulders with a burden on each side. The stick and burdens revolve. Bill set it casually on Asher’s desk and, twirling it, said, “I thought of you when I saw it. I know a producer has to have something to do all day.”

Ardis would love to go on all these trips, but the wrench of leaving the children is usually too much. When she and Bill spent three months in Europe with the Billy Wilders, she had a wonderful time—after the plane left the airport. She saves her tears for the trip to the terminal after the goodbye to the children. At that time Bill’s enthusiasm for traveling is slightly dampened, too. But new experiences have fascinated him all his life.

Even in his boyhood, being told was not enough. He had to experience. When his mother and dad returned to South Pasadena after a trip to Minnesota in 1932, an indignant note was conspicuous on the kitchen table. It was written by Bob, age eleven, in hearty disapproval of his fourteen-year-old brother’s use of temporary freedom.

“Bill has done the following while you was away. He:

1. Smoked (got sick inhaling)

2. Swore (used the Lord’s name in vain)

3. Drove fast (wouldn’t let anyone tell him)

4. Bossed (like only one in the world)

5. Dishes (said for me to set, remove, stack, wash and put away)

Bible—Right Hand Bob Beedle”

There was a drawing of the Bible in the left-hand corner of the note to prove that Bob’s wrath was righteous.

At sixteen, Bill still “drove fast”—for a reason. He wanted to be good enough on his motorcycle to join Vic McLaglen’s corps of trick daredevils. The desire to perform in the Rose Bowl and the Coliseum prompted his performances on the street in front of his home. For admiring crowds and a few bets he would stand on the seat of his motorcycle with arms outspread and glide dramatically down the street. This “Look, Ma, no hands” routine made his mother doubt that he’d ever reach maturity.

But during this trial-and-error period Bill was also learning to become a responsible citizen. His father made the full effort for his three sons: Bill, Bob and Dick. He taught them the value of physical coordination and the ability to earn their way. Their allowances were based on their duties. Bill spent the summers working as a surveyor for his dad’s chemical laboratory. His duties included unloading feeds, plants, oils and fertilizer from ships and trucks. He dumped full boxcars of steer blood, fish or bone meal. He ended those hot summer days with layers of the smelly stuff clinging to his body.

There are more pleasant means of livelihood, and Bill found one. Milton Lewis, Paramount talent scout, discovered Bill Beedle, twenty, making the part of an eighty-year-old man believable at the Pasadena Community Playhouse. At the time, Bill was going to South Pasadena Junior College studying chemistry. As George Seaton, his very good friend, puts it drolly: “His choice was simple—acting or the fertilizer business.”

Even though Bill decided on acting for a career, Lewis had to be patient with his discovery. It seems Bill Beedle couldn’t come to the studio until he’d finished his exams. Lewis was wise enough to wait. Finally, Bill showed up, worked on a script, screen-tested with a girl named Rebecca Wasson, and got an option for six months at fifty dollars a week with Paramount. The only history-making event of that period was his acquisition of a new last name—Holden, borrowed from a newspaperman.

Bill’s first big break came while Columbia was searching for just the right boy for “Golden Boy.” They were also interested in Rebecca Wasson’s screen test. Bill Perlberg, the producer, sat through the run of the test and then commented, “I’ve found ‘Golden Boy.’” From that moment to this, Holden has been golden for the two studios that split his contract between them—Columbia and Paramount.

Even as a newcomer, he was not afraid to express his opinions or roar when he’d had enough. For “Golden Boy” he had to learn to finger a violin and box and act as well as dye and curl his hair. He would take just so much of the daily rehearsals and workouts at the Hollywood Athletic Club, then come down with a thud and refuse to do any more until the next day.

It was Barbara Stanwyck who did for this newcomer what they say stars won’t do. She worked with him, helped him, gave him the best camera angles, finally insisted on having the set closed when she realized that the sudden avalanche of interviews was completely bewildering him. It was then that Bill formed both an undying admiration for Miss Stanwyck and a deep reticence with the press. To this day, he sends Barbara roses on her birthday.

With “Golden Boy,” Bill got his taste of overnight triumph. He liked the flavor. Sharing a small house in the Hollywood Hills with his dialogue director, Hugh McMullan, he started to work with a vengeance. As they were close friends, Hugh worried about the dedicated young man he lived with. Bill worked constantly. He drove himself with a grim determination. He was learning. He had to be better. Bill’s basic values have changed very little. Much later a reporter asked him, “What’s your goal?” Squirming at the direct question, Bill said, “I don’t want to sound corny. I want everything to be better. Personally, I think wanting everything—and I mean everything, mind you—to be better is the Divine wish.” After this untypical revelation, he switched the subject to his love for slapstick comedy, the Three Stooges in particular.

Deciding that romance might sway Bill’s one-track mind, Hugh carefully planned dinners to include attractive stars and starlets. Bill was charming, courteous and not at all interested.

Hugh thought Bill might enjoy meeting Brenda Marshall, who was going through the throes of a divorce. But Bill was afraid to become involved at that time, particularly with an established star who had a little daughter. When he ran into her on the Warner lot, he changed his mind—quickly. And Hugh’s worried about Bill’s one-track mind faded. In fact, after Bill had courted Ardis for twenty-two months, Hugh had to find a new housemate. Brenda Marshall, movie star, became Ardis Holden, with a new career.

Although the Holdens were married in ’41, “Getting to Know You” did not become their theme song until after the war, you will remember. Then it was that Ardis became a very wise woman and accepted the eccentricities of her spouse. Oh, she can level him if he overdoes. They still have healthy arguments, but with undertones of humor and respect that make these spats good outlets for two lively temperaments.

Bill has some rather fascinating foibles. He takes at least four showers a day. The first, accompanied by a lusty baritone, is followed by a loud stomping to the breakfast room. He doesn’t eat much, but he expects company at the table. When he arrives at the studio, he takes another shower. At noon and before leaving the studio, he manages to wet down at least twice more. He is sure that he catches cold through his feet, and spent quite a lot of time picking out the right rug for his dressing room.

He does his own stunts in pictures. In 41 he wanted to be a junior Gary Cooper. He rides and draws his guns like Cooper. He is a sentimentalist. Working fifteen hours a day, he nevertheless found time to design a gold medallion with two heart-shaped hands pointing to the numeral twelve—for Ardis on their twelfth anniversary.

He is inconsistent. He drove a secondhand car (purchased from Lucy and Desi Arnaz) for five years. He talked about a sports car so much, however, that the kids saved their allowances and presented him with a box marked “Daddy’s car.”

On Christmas, Ardis handed Bill a very legal-looking document (remarkably like a divorce subpoena) and said, “Sorry I had to do it this way.” Bill turned pale green and took the document. It was an order for a new Cadillac. When they went to get it, he was thrilled and doubtful. It was a Cabot gray convertible with an extra continental kit that extended the body another foot. “I guess it hasn’t too much chrome,” Bill said hesitantly, “but it’s sure going to make me feel like a movie star.” He still feels conspicuous in it. And yet in Europe he developed a yearning for a flashy racing car loaded with gadgets.

Bill has a mad passion for the musical bones and drums.

Holden is a man of varied interests. His paintings include many Paul Clemens pictures (among them a portrait of the family, over the living-room fireplace). Toulouse-Lautrec, Goya and Bangwyns’ “The Feast of Lazarus.” His record collection includes everything from jazz drum solos to symphonies and classical (he doesn’t care for opera). A gourmet, he likes hamburger with sour cream. He had a fabulous gun collection, but gave it away when he realized it was dangerous with growing boys around. He rides beautifully, swims well and submerges for half-hour intervals with an oxygen tank in the pool to be alone. He has done ten pictures in three years. Everybody swears by him and no one swears at him—an unprecedented record for a man who’s spent fifteen years in any business.

His children respect him because he knows Dale Evans personally. If he makes a Western, his stock will shoot up on the home front. In race-track lingo, he says his role in “Sabrina” was “by Brooks Brothers out of El Morocco.” He has mounted on his desk the Golden Apple award from the Hollywood Women’s Press Club for the most co-operative actor of ’51. Milton Lewis, the talent scout who caught that intangible spark in Bill Beedle in 1938, prizes the miniature golden Oscar that Holden sent him after his “Stalag 17” triumph. Even more, Lewis prizes the simple note that came with it: “We finally made it, Milt.”

Actually, Bill Holden is just at the start of a new phase of his life. Respected and honored in the industry, he plans to continue to grow (he’ll eventually be a director-producer). At home, the volcanic rumblings are fading. He and Ardis may one day do a picture together. His hunger for travel is being appeased. He and Ardis took off last Christmas for Greenland to entertain the troops. He’ll entertain troops anywhere, but the mere mention of Greenland brought that look to his eye. He has perfected his professional manner to the extent that he probably believes he is almost like any other successful business executive.

He’s the man who finished “Sabrina” Thursday evening, left for Tokyo Friday morning for “The Bridges at Toko-Ri” and arrived back Christmas morning ready for “The Country Girl.” Tired, he called George Seaton and asked for a couple of days off to go to Palm Springs and soak up the sun. The holiday was granted. But the next day George got a call from Palm Springs. “I’d like,” said the worn-out actor, “to rehearse.” So Bing, Grace, George and Bill spent that weekend rehearsing in a church in Palm Springs.

He’s the man who roars, “I’m going to Palm Springs alone and rest!” He is also the man on the phone the next day begging Ardis to join him.

He’s the man who made a game of walking the rail of Suicide Bridge in Pasadena—on his hands! He was ten then, but the spirit of adventure, lack of fear and occasional deviltry have never left him.

Yes, some people say he’s staid, stuffy, dull and colorless. Others say he is a breath of fresh air and wish we had more actors like him. Some say he wages war on trifles because he feels guilty about his lack of real problems. Some say he could be a hypochondriac if he let himself go—but only between pictures. His good friend Paul Clemens says, “Bill is at times his own worst enemy. But since he is such a good fellow at heart, he finds himself pretty slender opposition.”

Everyone agrees that Holden is Golden. And gold is a very colorful color.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1955