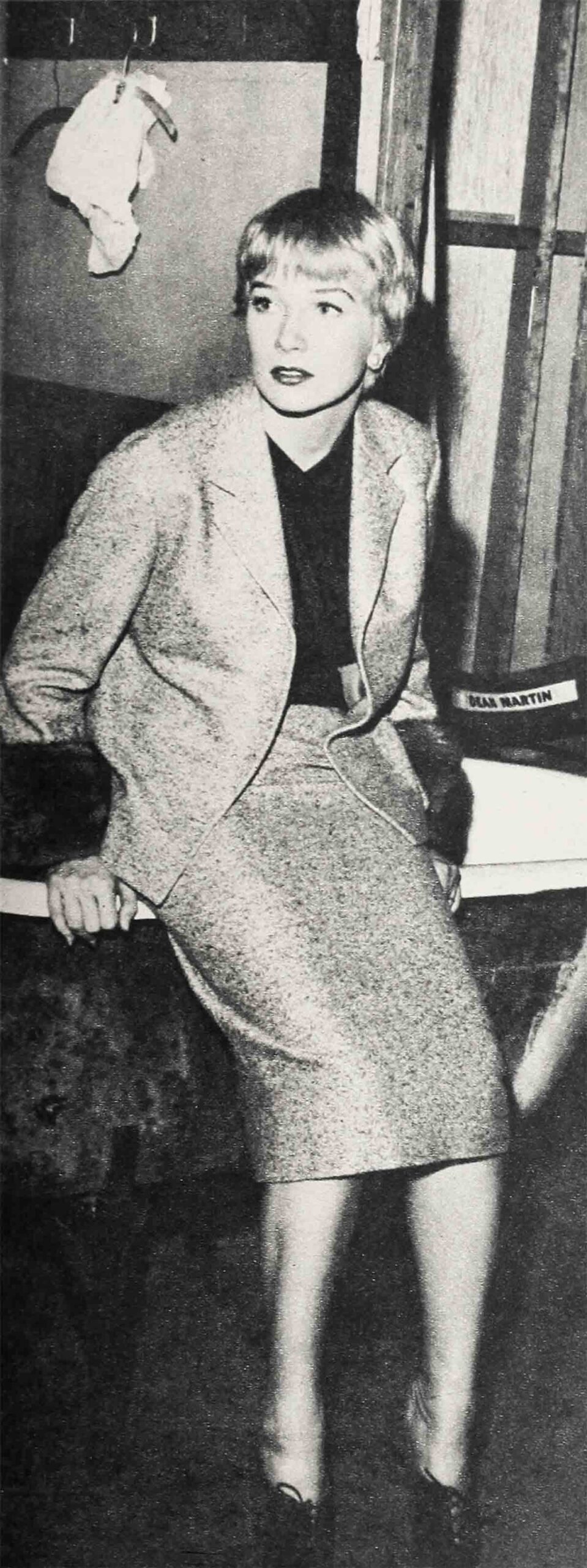

A Little Bit Kooky—Shirley MacLaine

Hollywood, which suffers from prose lassitude of a sort, has determined in the past year or so that its brightest current property, Shirley MacLaine, is, if not beatnik, at least kooky. Kooky means very far out indeed, which in turn means kooky, and it all seems to suggest that Miss MacLaine would wear a beard if she could grow one. The matter is not even helped by her true last name, which if pronounced correctly could be made into Beaty-nik.

This too-easy identification distresses the lady; not terribly, but some. Though she herself has said, “I’m so far out, I’m in,” she means something by it. She means, and she says, that she is embarrassed by professional eccentrics, whose motives she distrusts and whose eccentricities, alleged, she does not believe in.

“I don’t work at it,” she said not long ago. “If I’m a little bit kooky, it’s because I am. Everything I do seems all right to me or at least no one in a white coat’s going to get me.”

This was at lunch. Miss MacLaine was making “Can-Can” for 20th Century-Fox, a picture she thinks may be finished some time, but this was last summer and they were still going to be shooting in November.

She took an exhausted looking piece of gum from her mouth, wrapped it carefully in a paper napkin, and forbade the waitress to take it. “I like old gum,” she said. “New tastes funny. I’ll save it for after I eat.”

“And you’re not far out?” said a companion.

“Not really,” she said. “What’s far out about old gum? Most gum is old.”

But this piece of gum had a history more elaborate than most. It had spent a part of the morning behind Frank Sinatra’s ear. Very few wads of gum can say that. Miss MacL., who chews gum habitually, is starred opposite Sinatra in this picture whose name already has been mentioned. For a scene she had to remove it and couldn’t find a place to stash it away for future use. So she put it behind Frank’s ear. Well, of course. Then he forgot about it and the next scene was a closeup featuring in part the back of Sinatra’s head and there he was, complete with gum. That take went for nothing.

“It was the closest ear there-was,” said Miss MacLaine now, defensively. “You wouldn’t want me to put it on the floor, would you?”

“The word persists,” said her table companion, “that you are in orbit.”

“You know me. Would you say I was?”

The answer is not easy. It depends to some extent on what one means by orbit. Shirley MacLaine is, in the most attractive sense of the word, funny-looking. She is remarkably lovely and she has a clown’s face. It is about as facile as a face can be. Persons who saw her in both “Some Came Running” and “Ask Any Girl” know about this. It is part of her brilliant versatility as an actress, who cannot be feazed by either comedy or pathos. When “Can-Can” is released in the spring, they will meet yet another edition of the girl. Part of her special quality, which is as hard to define in words or by still camera as the face of Audrey Hepburn, is due to the fact that she seldom parts her lips when she smiles. This gives her a look at once smug and elfin. The smile is characteristic and- not a practiced grimace due to irregular teeth or anything of that nature. She may understand that it goes well with her social personality; she is an astute judge of herself as an actress. Another inseparable part of her is her short, careless hair-do, apparently derived vaguely from a style once called the Italian cut. So closely is she linked with this that a friend meeting her on the sidelines of the sound stage of “Can-Can” did not recognize her; she wore a long blonde wig.

Those who know her know she does not drink—“coals to Newcastle,” one has said—yet at a Hollywood party for which she performed, she was suspected in print of having tipped a few. Hollywood does not always recognize natural exuberance.

This same abstinence sometimes sets her apart at drinking parties, where she will dutifully greet her host and hostess on arriving, then depart the main room to spend the evening at gin rummy—sometimes with the host and hostess. Once during one of her rare night club excursions, she felt an uncontrollable urge at three in- the morning to go home and clean her house. She did so.

She professes a deep regard for sleep, yet says in the next breath that she rarely gets more than four hours a night. When working, she gets to bed about two and gets up at six. But it is in the waking minutes that her fondness for rest gets its strongest hold.

“Some day,” she has said darkly, “I’m going to be out of the house and on my way to work two minutes after I get up. It’s my great challenge.”

“Ever done it?”

“I’m working up to it. Three minutes and forty seconds is my record so far.”

It is no mean record, and made possible by the circumstance that she never eats breakfast. Some days she doesn’t eat lunch either, and on a few occasions skips all three meals. When these periods of unthinking starvation—they are never forced—come to her, her appetite attains fierce momentum and in the end she falls on a meal of Marine proportions, devouring as if there were no tomorrow and chewing little enough as to alarm an expert on the functioning of the digestive tract. Shirley also gets fixes on certain foods and becomes impatient of variety. “I’ve seen her eat her weight in fruit at one sitting,” a friend says. “Nothing but fruit.”

As a healthy and amiable girl, Shirley MacLaine can be said to have very few dissident quirks of personality, but some of these have come about as a result of the overwhelming volume of publicity that lately has come her way. At the time of a recent interview, she had appeared twice on the cover of a national picture magazine and once as star of the cover feature of one given ostensibly to news. Another picture specialist would cover-blurb her a week from then and a monthly publication was coming up with more of the same. The heroine of all this was more concerned than otherwise.

“It’s all pretty wonderful,” she said, “but there’s bound to be a saturation point. People are going to get good and fed up with looking at this face and reading about this me.”

She was called to the phone and excused herself. While she was away, a studio spokesman said to the other person, “She’s putting her foot down on all this about how she and Steve are 6,000 miles apart much of the time.” Miss MacLaine’s husband is Steve Parker, who is not an actor but looks more like an actor than most actors; a handsome, moustached man whose production activities keep him in Japan a great deal. “She’s afraid people will think she can’t remember his last name. Which, of course, she can. Besides, Steve has been in the (Hollywood) vicinity lately because of the success of the Japanese show he brought to Las Vegas.”

The interviewer, who had as well a nodding social acquaintance with the Parkers, bore this in mind. but asked when she came back:

“How’s Steve?”

“Steve who?” She got the reaction she wanted—bewilderment—and then said, “Steve’s fine.”

She is worried also about any further pictures of her truly adorable baby daughter, Stephanie, who has been building a public of her own via so much photography. Stephie, as most call her, not only is cute but is, in her mother’s opinion, becoming aware of it. This Sounds precocious but Shirley MacLaine Parker does not wish to risk her only child’s growing up a ham.

When Shirley MacLaine says she is not self-conscious, she speaks nothing less than the truth. A French philosopher of note once admonished his readers: “Never apologize, never explain.” While Shirley may not carry self-containment quite this far, she still feels patently that she has nothing drastic to answer for, and it is an attitude that gives her superb outer aplomb. A close associate’ has said of her, “If she lived in a cave and you visited her, she wouldn’t say a word about how the place looked. Wouldn’t even think of it. She hasn’t that kind of insecurity. Inside she may be a little scared—not that I think so. But you’ll never know it from her.” She loves to swim but must do so either in early morning or at night; the sun mars her sensitive skin. Yet she is one of the few women not in the least disturbed by wearing on her legs neither stockings nor a tan.

Naturally, she does not live in a cave. She lives in a pleasant home on the southern slope of the San Fernando Valley that probably would be called “ranch”—a California word for any architecture not definitely Tudor, Spanish or modern—and has a driveway so angled that it is almost impossible to get onto or out of without two tries. Before that, when Stephie was a babe in arms, she lived on the beach in Malibu and swore lovingly she would never live any place else, and later on a hillside which likewise she was never going to leave. Despite her disinclination to discuss the matter, it is thought by those closest to her that Shirley MacLaine does get lonesome and-does channel her devotions, those not lavished on a Stephie toward inanimate objects and possessions. She is emphatic and entirely truthful she says, “I don’t give a hoot about sessions!” but the energy of a need to may seek outlets.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE JANUARY 1960