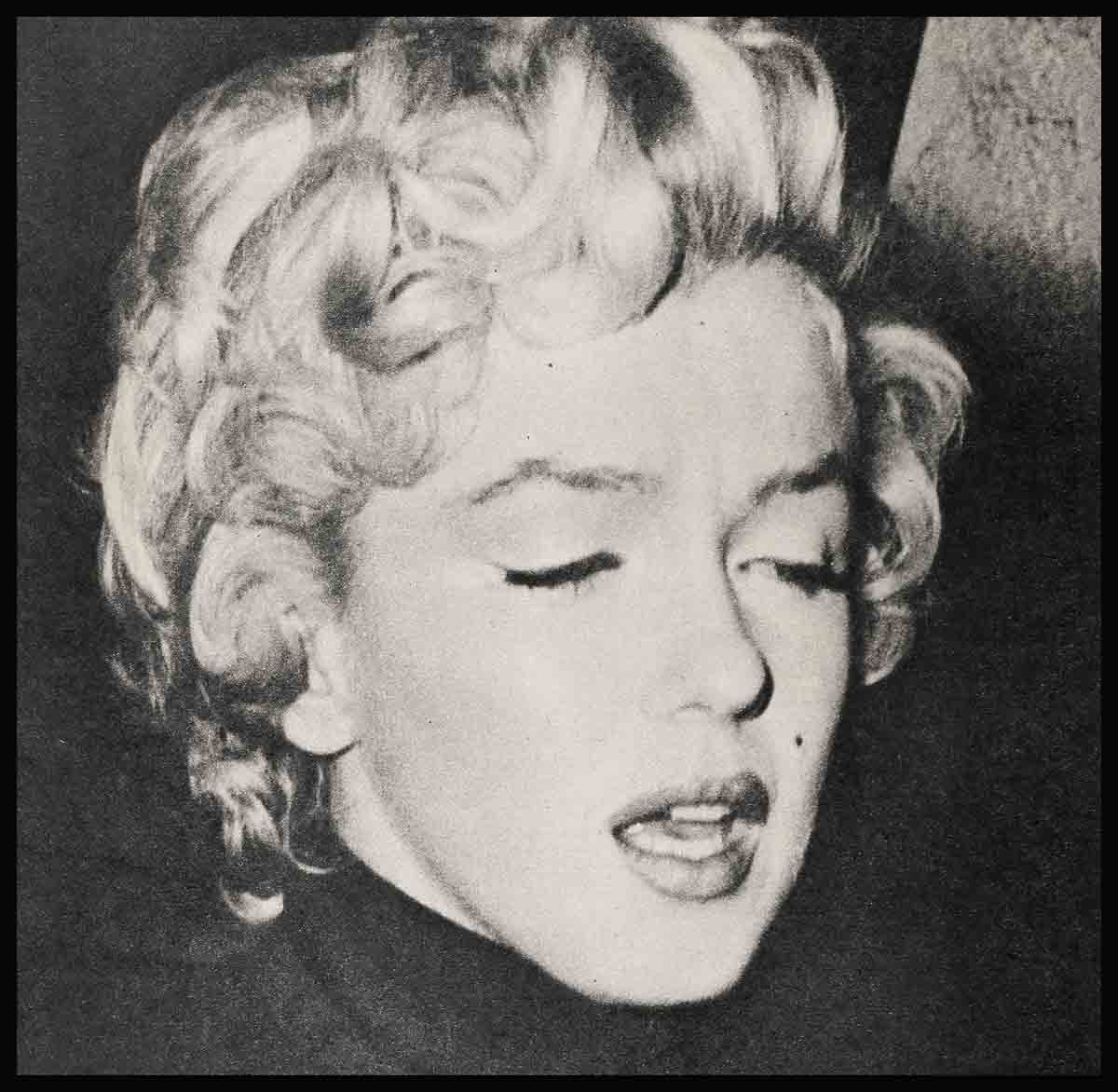

“My Darling, Daring Daughter”—Terry Moore

It was close to midnight when I watched the giant TWA Constellation take off from Los Angeles’ International Airport, bound for New York, with two of the people closest to me on board: my wife, Louella, and my daughter, Helen, better known to her fans as Terry Moore.

My eyes followed the plane as it climbed several hundred feet, going into a gradual half-turn over the ocean, then swinging eastward, heading into the darkness. After it had disappeared, I slowly walked over to the parking lot and climbed into my car.

The drive back to Westwood gave me ample time to think about a question I’d been asked the day before. A neighbor wanted to know how I felt about my daughter’s career. He’d heard we had sold our house because Terry decided to move to New York more or less permanently to study dramatics with Sandy Meissner and commute to California only for pictures. He also knew that once again Mrs. Koford was going with her, although this time she planned to return to Los Angeles after a week, when Terry would be more settled.

As a father, I am primarily interested in my daughter’s happiness. No matter how much I, personally, would love grandchildren, to me it is of secondary importance whether she achieves happiness through marriage and raising a family of her own, or by concentrating on her career. However, since for the time being she has decided on the latter, in my opinion the results must warrant the efforts. And by that, I don’t mean the financial returns, but the satisfaction Terry gets out of her work.

Evaulating my daughter’s life, I can see fragments of exhilaration and happiness, notice the joy she draws out of good parts, the excitement of starting a new picture, the satisfaction of being liked by so many fans. But neither can she hide her moments of disillusionment and despair. The question is—of which is there more? Is one worth the other?

Even for someone as close to her as I am, her father, this is difficult to answer. This is why I can’t state in a few, simple terms how I feel about my daughter’s career. Too many aspects are involved, many more than the trips to the airports or having to fix my own meals occasionally.

Frankly, at first, I was not in favor of Terry’s career. I was afraid her formal education would suffer (she was only eleven when she started), that she might meet the wrong kind of people, let all the attention go to her head. But knowing how much she wanted to get into show business, and with her mother at her side, I let Terry accept her first part.

As it turned out, most of my fears proved unjustified. Thanks to studio schooling, her education progressed satisfactorily. While I didn’t and still don’t approve of all her friends, the majority are fine, hard-working, decent folks, like you’d meet in any type of business. But the price of prominence has its setbacks, particularly for a sensitive girl like Terry.

She has always reacted strongly to what others said or felt about her.

The Korean bathing suit incident in 1953 is a typical example. I’m not going to argue the pros and cons, defend or deny. Enough has been said about it already. Too much, as far as I am concerned. I just want to add that only her mother and I know how Terry really re-acted to the unfortunate publicity.

My daughter is equally sensitive about almost everything else. When she was criticized for the way she dressed or posed, she became quite upset. Actually, she dresses quite conservatively and simply, except when she goes out on official functions and feels her fans expect her to wear fancy clothes. I have watched the photographers tell her how to pose, and Terry does it because she feels they know their business and because she wants to be cooperative. That is one of the strange contradictions which wouldn’t matter if she didn’t react so strongly to what people say. Were she hard-boiled and indifferent, she wouldn’t get hurt so easily.

This sensitivity in a business where there’s little room for personal feelings is a handicap for Terry. At the same time, I’ve been told by some of her directors that it is one of her biggest assets as an actress. It gives emotion and depth to her performances. So I guess the advantages and the disadvantages in her personality go hand in hand in acting.

There are many other facets of my daughter’s personality, of which, I believe, few people outside her immediate family are conscious. Her generosity, for instance. Terry herself will never bring it up. Particularly as to what she has done for her brother.

It was Terry who helped Wally through college, without ever giving him a chance to thank her. She paid for his tuition, books, room and board and other expenses.

I believe Terry did this out of more than sisterly love, although she and Wally have always been very close. They have always stood up for each other no matter what the occasion or possible repercussion. In her brother, she visualizes some of the ideals on which she missed out. A complete education, for one.

Terry always had tremendous desire for learning. As a student, her grades were far above average in arithmetic and chemistry. She learned easily, quickly, hungrily. Somehow she never got her fill.

One of the disappointments connected with her career was that it kept her from completing her college education. She has been making up for it in her spare time by taking extension courses at U.C. L.A., and has already the equivalent of two years of college. But the going is slow and difficult because of the limited time she has available.

Where she missed out, she wanted to make sure that Wally had a chance to complete his education. I think she was more anxious to see him graduate from Brigham Young University than he was.

Terry helped Wally in other respects. Like the time when her brother decided to go out as a missionary. She showed her enthusiasm in a practical manner.

When Wally first brought up the subject, Terry cried out, “That’s a wonderful idea.” Then a thought struck her. “How will you get around?”

Wally hadn’t considered it. “I’ll find a way.”

Terry didn’t say any more, but a few days later, she made the rounds of used car lots and the following Christmas gave Wally his first car. A pretty generous present even for a girl with Terry’s earnings. Today, Wally’s in the southern part of the United States for the Mormon Church. He has no more enthusiastic rooter for his work than his sister.

All her life, Terry has been extremely generous. She started earning money when she was eleven. As her business manager, I had to see that she saved a good part of it. If she’d had her way, most, if not all, would have gone into presents for her friends and relatives. She’s never changed.

Being sensitive herself, she realizes how others might feel about accepting gifts and takes care to give in a way that will not embarrass.

For instance, she has a girl friend who right now can just about afford the bare essentials of life. Wondering how she could help her unobtrusively. Terry decided to give her clothes. And I saw how she went about it one afternoon when her friend was visiting us.

The day before, Terry had bought three attractive new dresses. When her girl friend came over, Terry tried them on, decided two “didn’t look good” on her. “You’d do me a favor if you’d take them,” she begged. “They’d just be crowding my closet.”

“But they are brand-new!” the girl burst out. “Why don’t you return them?”

“I wish I could. But they were bought on sale and the store won’t accept returns.”

As a matter of fact, she had bought them at a sale—but precisely so she couldn’t return them! That settled the matter.

It is quite amazing that a girl who’s earned as much as Terry has so little sense for finances. Although I’ve talked her out of many gambles, I can’t always buck her enthusiasm and impulsiveness for new projects. Only a few weeks ago she confessed she’d invested in a new type of water heater. Offhand, it sounded quite promising. We never had a chance to investigate it closely because the man who sold her the stocks suddenly disappeared. He’s still “missing.”

Terry comes to her mother or me for advice on most matters, not just those concerning money. For that matter, we have always been very close in spite of, or maybe because of, the strictness with which we have raised our children.

Till she was out of her teens, we were firm about having her home at a certain time, about first meeting the boys who took her out on a date, about her school-work and other things.

Yet we tried to assert only a minimum of parental authority, preferring to be pals rather than disciplinarians. Even today, when Terry is in Los Angeles, before she goes out with a fellow for the first time, she invites him to the house and introduces him to her mother and me.

And when she comes home from a party at night, she tells us where she’s been, what she’s been doing, how good a time she’s had.

Her mother usually stays up till Terry gets back. Being a working man, I try to turn in early. When Terry comes home and doesn’t find Mrs. Koford in the living room, she tiptoes into our bedroom to see if she’s still awake. But while my wife and daughter can keep down their voices, Terry’s miniature poodle usually gets so excited that her barking wakes me up anyway, till I’ve decided it’s easier to stay up, too.

Terry had never intentionally kept anything from her mother and me, with one exception. And that because she knew that the only thing I worried about was her own lack of fear. She’d try anything!

No incident stands out more clearly, more frighteningly, than the Sunday that almost cost her life. She had just turned six when it happened.

Terry, my wife, my sister-in-law, my nephew Ben and myself had gone on a picnic to Griffith Park. While we grown-ups were talking with one another, Terry and Ben disappeared. They had taken off for the nearby zoo.

Terry still had a peanut butter sandwich left when she and Ben reached the lion’s cage. “Let’s give him the rest of our sandwich,” she suggested to her cousin, who was quite willing. But the double ring of walls prevented her from throwing it into the cage. That didn’t deter my daughter, who was determined the lion should get his share of her lunch. He almost got Terry as well.

Investigating the maze of entrances and gates, by a nearly tragic coincidence she found her way inside the compound through a left-open gate, and with Ben trailing behind her, walked into the lion’s den right behind the keeper, who was carrying in a load of raw meat.

In the meantime, the rest of us—having noticed the children’s disappearance—started to look for them. It was Mrs. Koford who happened to spot Terry just as she was offering her sandwich to the ion.

She let out a scream that made the exasperated keeper whirl around, grab Terry and Ben by their arms and practically throw them both out of the cage.

Yet after my daughter was safely in her mother’s arms again, her only concern was fear of punishment for having walked off during the picnic!

Terry never lost this daredevil attitude, which is responsible for most of my gray hairs! When she was nine I caught her clinging to a boy’s waist as he raced past us on a motorcycle, a good seventy miles per hour. But the pay-off came shortly after she turned twenty-one. I don’t know how Terry got interested in flying, but as with everything else, once she began, “there was nothing like it.”

She knew if she told us, we might worry. Besides, we might have asked her to discontinue her lessons. This chance she didn’t want to take. The easiest solution, she reasoned, was to get her license on the q.t.

She made excellent progress till one Sunday afternoon when her instructor called up to ask where Terry was. I told him I didn’t know.

“That’s too bad,” he gave himself away. “Terry’s supposed to solo today.”

“Terry flying?” I burst out.

“Didn’t she tell you?”

“Of course not! Now you tell her . . .”

It was too late. Just then her instructor saw her pilot the plane along the runway, ready to take off.

“But don’t you worry, Mr. Koford,” he assured me. “She’s one of the best pupils I’ve ever had.”

Since she’d gone that far, I didn’t want to stand in her way. And I loved her doubly for keeping it from her mother and me. It showed her concern for us. But I’ve never gone up with her.

Most of my worry about Terry, however, is about her driving ambition, her restlessness, which won’t let her relax, which keeps her far too tense for her own good.

This attitude is understandable, and I presume necessary when she’s working on a picture. When they work, most of her friends who are in the same business get up at five or six in the morning, often don’t get home till after dark. But at least in-between pictures they ease up.

Terry, on the other hand, works even harder when she’s not in a picture, cramming her days and evenings so full of lessons—dancing, dramatics, voice, half a dozen other projects—that she has less free time than when she’s filming. Even on Sundays, when lying in a deck chair on the back porch, she always has a couple of scripts by her side. Nor would she leave her work at home on vacations.

Just before she went into “Daddy Long Legs,” Terry became so run-down that I decided to take her and her mother to Palm Springs for a few days.

The first morning after we arrived, she slept till ten. The second morning I found her up at eight, by the pool—once again studying a script.

Terry will have to learn to relax. To be honest, however, I’m afraid till she’s on top in her career, her ambitions won’t let her, and there isn’t much her mother and I can do about it.

What will happen to Terry in the future?

Someday she will get married again, I’m sure. But when she does, I hope she will give up her career for her sake, and that of her husband-to-be.

Some girls can combine a marriage and a career. My daughter would have a difficult time making a success of both, simultaneously. And since right now show business is her life, I hope she will soon reach that pinnacle of success on which her heart is set so that she can then look forward to a different kind of happiness and satisfaction—marriage and raising a family of her own.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955

No Comments