Ready, Able And Prating—Gordon MacRae

The day last spring, when the papers reported that Frank Sinatra had been signed for the lead in “Carousel,” one of my closest friends came over to the golf course as I was rounding the eighteenth green.

“This must be a tough blow to you, Gordon,” he said, referring to the newspaper reports. “You so completely believed that after making ‘Oklahoma!’ you’d get this picture, too.”

“I still believe it,” I told him.

He stared at me dumbfounded, and I didn’t blame him. On the surface it was a strange thing to say. The moment I’d seen the papers that morning I’d checked with my agent, and it was true: Frankie Sinatra was signed, sealed and delivered to star in “Carousel.” The whole sky seemed to turn black as I read those words.

Yet my faith was still strong upon me, just as it had been when I started campaigning for the lead in “Oklahoma!” Then, everybody told me that a guy who’d been off the screen for a year was really cracked to even try 4 to go after that one. Sure, Rodgers and Hammerstein tested me for Curly in “Oklahoma!”—but they tested just about everybody in town besides. For six months, while these tests went on and on, I went around Hollywood wearing the kind of boots I knew Curly would wear in the picture. For six months, as I read about this singer and that being considered, I let my hair grow long. And my wife Sheila actually set it in pin curls for me, so that when I went out, it would look the way Curly’s hair should be. I also went around with cowboys and learned their lingo. I lived, breathed and slept Curly.

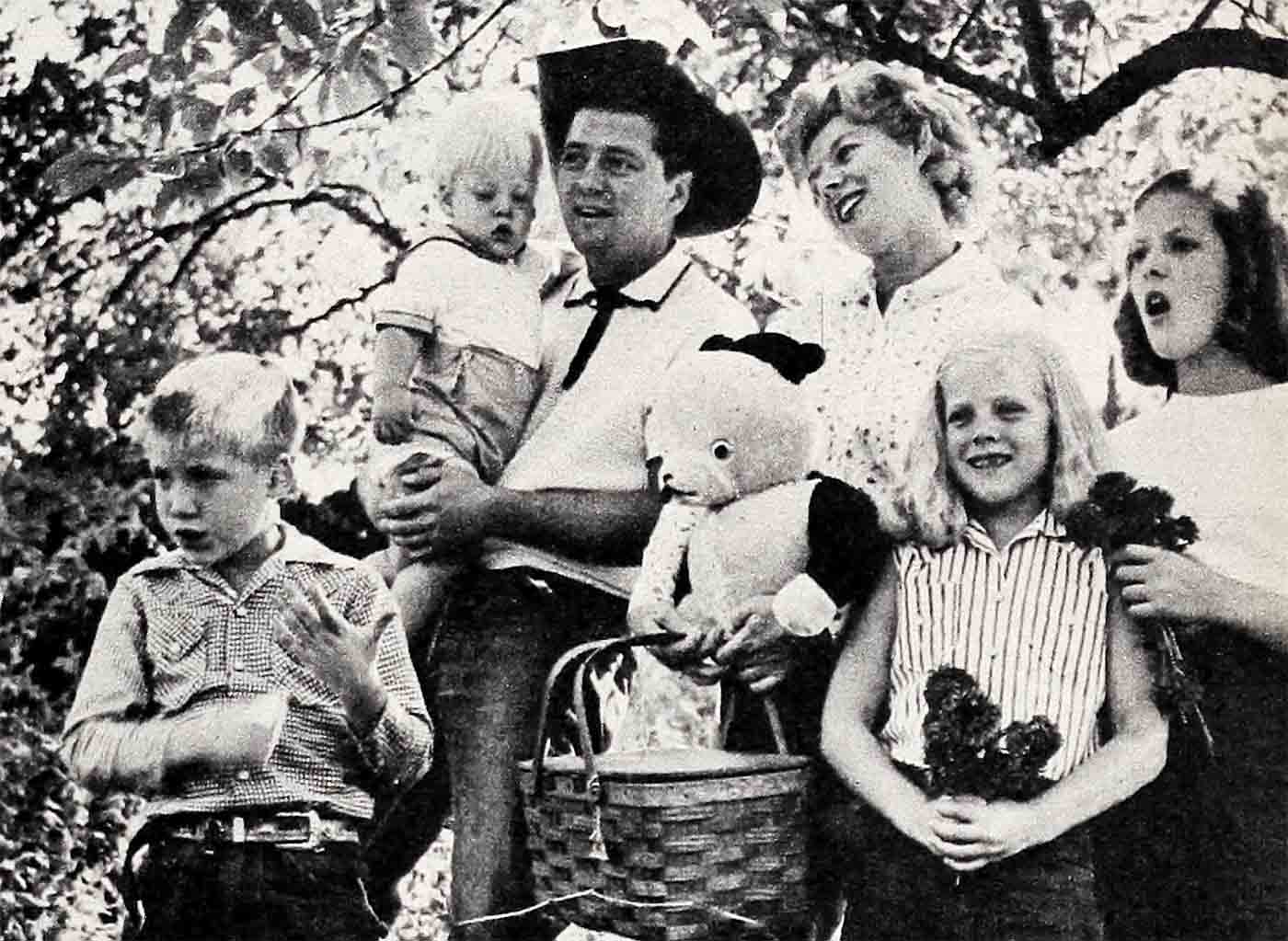

I think Sheila is the best wife in the world. Of course, never having had any other wife, maybe I’m prejudiced. But believe me, on the basis of almost sixteen years’ acquaintance and nearly fifteen of solid marriage, I can’t see how any girl could be greater. Sheila has given me two daughters and two sons. She’s bringing them up wonderfully. All these years she’s put up with me, my forgetting to come home to dinner on time, my often making her a golf widow, my constant singing. Besides, she’s a doll to look at.

But, so help me, I think the time I appreciated Sheila most was when I was on the kick of getting “Oklahoma!”—or else. The “or else” was that if I got “Oklahoma!” I believed I’d get “Carousel,” and I’d had my heart set on doing “Carousel” since 1948.

Or, looked at in another way, it was what I’d been aiming for since I was sixteen and determined to be a singer. My father ran a machine shop in Syracuse, New York, and he had hoped I’d join in the business with him. But, always having loved music himself, he sympathized with my intense desire to sing and didn’t try to stop me. I was still in my teens when Dad died so, instead of going on to college as planned, I went to work. Eventually, I got a job acting—for the grand sum of five dollars a week, plus room and board—at the Mill Pond Playhouse in Roslyn, New York. It was there I met Sheila, who also had acting ambitions, but less than a year later gave them up to marry me.

Later, I joined NBC as a page. One day, Horace Heidt happened to hear me exercising my vocal chords in the lounge and, in need of a singer, he asked me to join his orchestra. After touring and singing with him for close to a year, I appeared on Broadway for the first time in “Junior Miss.” Then I sang with Ray Bloch’s orchestra and on CBS Radio until the war caught up with me and I joined the Air Corps, to become a bombardier.

I mentioned having wanted to do “Carousel” since 1948, because that was the year I started in movies. I had appeared in the Broadway musical, “Three to Make Ready,” with Ray Bolger, and after that was signed by Warners. And, once I had my foot in the movie door, I began directing my dreams toward the day when “Carousel” would be made into a picture and I’d play the lead role.

Today, I’m delighted that our daughter Meredith, who’s eleven, knows that she wants to be in show business. As a matter of fact, she makes an appearance in “Carousel,” and she’s swell in it, too. Nothing will please me more than if the rest of our gang—Heather, Gar and Robert Bruce—when they get a little older, make the same decision. Because I’ve gained nothing but happiness from my determination, back there when I was a kid, to sing for my supper and everything else. I loved show business then, I love it now. It really burns me when I hear people knock it—particularly since, as I said, Sheila and I found each other through show business.

Sheila has tremendous talent. I never asked her to give up her career and, in some ways, I wish that she hadn’t. That’s just because I think she would have been such a smash, and had so much fun. Sometimes now she plays a night-club date with me, and she’s terrific. But she treats such an engagement as a lark and claims she prefers just to be my wife and mother of our brood.

That’s my private-life side of it. Professionally, all the seamy side of show business I’ve heard about, all that routine about a broken heart for every broken light on Broadway, and that other fable about the only way to get ahead in Hollywood is to double-cross and lie, are things I’ve never encountered. I’m not playing ostrich. I suppose they can be there. But the route has been easier for me—up until I began encountering Rodgers and Hammerstein.

I just plain love to sing. So if I coach three to four hours a day—and I do—that’s not suffering, as far as I’m concerned. I like acting, too, but music is a real passion with me.

So back in 1948, when a charming girl named Jan Clayton told me about a show named “Allegro” being cast for Broadway, I tottled around to see if they (Rodgers and Hammerstein) would listen to me. They conceded as how they would. They were listening to everybody then, just as they were listening to everybody, six years later, in Hollywood when they first began casting “Oklahoma!” If there ever were two men with open minds and ears, they are Oscar and Dick. I had to read the “Allegro” songs from the copy, which isn’t easy, but I managed it, and I thought I did pretty well.

They didn’t and another actor got the role. But I didn’t forget the two lessons that experience taught me.

Lesson one was about the value of friendship—in this case, Jan Clayton’s tipping me off about the audition.

Lesson two was the value of being pre- pared.

Out of these grew lesson three for me—the meaning of faith. The Bible says that faith without works is dead. That’s so true. Faith has to be backed up—by you. If you believe that your faith can give you the breaks—and I certainly do believe it—then you’ve got to give your faith a couple of breaks yourself.

For example, being ready for the break. In my own case, this meant being known as making a “comeback” when I made “Oklahoma!” Sure as Gibraltar, that’s what it looked like. But Sheila and I knew it wasn’t a comeback at all. I had been busy full-time with radio and TV work and night-club engagements. I’d been off the screen for more than a year deliberately. I’d deliberately gone to Jack Warner—who’s a very good friend of mine, incidentally—and asked to be released from my contract exactly one year before I was told “Oklahoma!” was mine.

I’d been a happy guy at Warners. I’d liked co-starring with Doris Day. I was making very good money. But I wanted out because I saw I was getting into one of the pleasantest ruts in the world—playing parts that were easy, singing songs that were easy, taking money that was easy, and letting myself get a little broad around the waistline. So I said to Jack Warner, “Let’s stay friends. Give me the privilege of parking my car on your lot any time, but shake me off the payroll.”

When you are under contract, you can’t go after the roles you want. You have to take what they give you. So I became a deliberately free agent in order to go after Curly and “Oklahoma!”

Immediately, Sheila and I began getting ready for it. And I do mean Sheila and I—plus Meredith, and Heather and Gar. The first thing I did was to buy the printed version of the play. I’d seen the stage production several times, of course, and I knew all the music Curly sang. But I wanted to know every word of the show.

A month or so later, I knew the whole score and script of “Oklahoma!” So did the entire MacRae family. Our house turned into a theatre, and night after night, Sheila played all the women’s parts. I played all the men. Sometimes our friend, Jeff Chandler, stopped in to play Jud, or our pal Gene Nelson would dance through one of the roles, or Dean Martin would try out his pipes on another.

Day after day, I dieted and rode horseback, dieted and coached vocally. Night and day I prayed.

I said to Sheila, “If the Good Lord wants me to get Curly, I’ll get it.” She said, “Why, Gordon, of course He does.” And we kept on working, dieting, praying.

Finally, as the weeks went by and the contest for the part narrowed, I couldn’t stand waiting around. So I flew to Spokane to play some golf. I was out on the links with a pro named—so help me—Curly when someone came running out from the clubhouse to tell me my wife was calling. or a moment I was panicked, thinking something was wrong with the kids. I raced to phone and said, “Hello.” “Hello, Curly,” said Sheila—and I knew.

We had hardly started working on “Oklahoma!” when “Carousel” was bought by 20th Century-Fox—and I started aiming for that one. The lead in “Carousel” is not only a singing but an acting role—a big acting role. So I began coaching, and I began praying. I bought the printed story of “Carousel,” and once again our home turned into a theatre. We learned all the music, and all the parts. And I started sending wires to Darryl Zanuck, another friend of mine.

Now let me digress a moment to say I’ve also heard a lot of stories to the effect that producers hate actors and vice versa. But I’ve never personally encountered this either. Why should producers and actors be at each other’s throats when both are after the same thing—the best possible picture? It’s the same as workers in any other trade hating the boss. What sense does this make? The boss can’t get along without you, if you are really good, and you can’t get along without him, if he’s really good. So why fight? Or why be jealous of other fellows in the same sort of job? I openly admire Dean Martin, and Jeff Chandler, and Gene Nelson and all the many other actors who constantly drop in and out of my house as I do at theirs, or whom I encounter on the golf links or in clubs. Personally, I believe you will learn more from the fellowship of friends than you could learn in nine colleges.

So I wired Darryl, and I wired Rodgers and Hammerstein. I coached and coached on the music. They listened—but I listened, too, to the rumors that it was Frank Sinatra whom they wanted.

It’s a curious thing the way that Frank’s and my career have overlapped. One of my biggest breaks came at the time that Frank was getting his first big break, back in the spring of 1943, when he was the rage of the bobbysoxers. One Sunday, he couldn’t show up for his CBS program. I’d just gone to church when CBS called me—the unknown Gordon MacRae—to come over to the studio to stand in for him. Fortunately, a friend (there’s that word again) took the call, chased down to the church for me and Sheila. CBS had said I’d have to be there exactly at noon. It was then five after twelve and I tore out of church and to a phone. “Give me ten minutes,” I gasped. Well, you know they did, or I probably wouldn’t be here now.

So, twelve years after, here were Sinatra and MacRae touching careers again in Hollywood.

Then I read he was signed. But my faith persisted. Why? I can’t exactly tell you why. I didn’t know why myself. But this much I knew. There isn’t as much talent in the world as people like to suppose—and I don’t mean just a talent for singing or acting. I mean the talent of being responsible, of doing your job well, of getting along with people, or being kind and of trying to make the other fellow happy because that way you will be happier yourself. No matter what your job, if you really do it well, and honestly like it, you are not going to get fired. And the break—the right break—will come to you, especially if you’re ready for it and work for it.

My break, with “Carousel,” was the craziest. Twentieth was making it in two processes, in two different widths. Frank refused to make the two versions for the salary he’d been originally signed for and broke his contract. I don’t know whether he was right or wrong in his stand. I have to admit I don’t even care. For he walked out—and I walked in . . . with God’s help, I’m perfectly sure.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956

No Comments