“V.J.” Day—Van Johnson

On a January night in 1943, a passenger train, with all car lights shaded, switched from the main line of the Southern Pacific, in the San Fernando Valley in California, onto a spur leading to the U. S. Army Debarkation Hospital in California. On it were the first American soldiers wounded in the Pacific battle area. As it steamed slowly into the hospital grounds, the bustle of reception activities became evident, and word, flying through the wards, was carried to a group of visitors. One of the women in this party, a member of the Volunteer Army Canteen Service, turned to a tall, blond, young man walking with her.

“Did you hear that, Van?” she asked. “These are the boys hurt in The Solomons. Will you come and help us welcome them? It’s one of the most important moments in their lives; they’ve come home.”

Van Johnson, who’d visited the hospital many times before, and had talked to thousands of European visitors, stared at her. A frightened look came over his face. “Lord, no,” he said. “I’d be petrified. Those guys must be grim after traveling thousands of miles to get here. I’d be the last person they’d want to see.”

They told him he was wrong. Against his judgment, they persuaded him to go along. When the first boy was carried off the train on a stretcher, Van was standing in the background. The soldier, like his mates now being taken from the cars, did look grim. His eyes were sunken, uninterested. He had been lifted and handled dozens of times; this was no novelty. Van Johnson swallowed hard, and stepped farther back on the hastily built platform. Then he froze. The first soldier had yelled something.

“Hey!” his voice rang out. “Hey, you guys! Look! Van Johnson!”

Another soldier took up the cry, craning his head from the stretcher. “Yeah! Hey, Van! I saw your last picture! Me and a million mosquitoes!”

Somebody pushed Van forward, and before he knew it, he was shaking hands with the boys and talking to all of them as they were taken from the train. Thus, the first Pacific wounded at Birmingham were greeted on their homecoming, and thus, they learned to know Van.

And these same Pacific boys—long before our actual victory over Japan—seized upon Van Johnson’s initials to designate his visits as their own kind of “V. J.” Day.

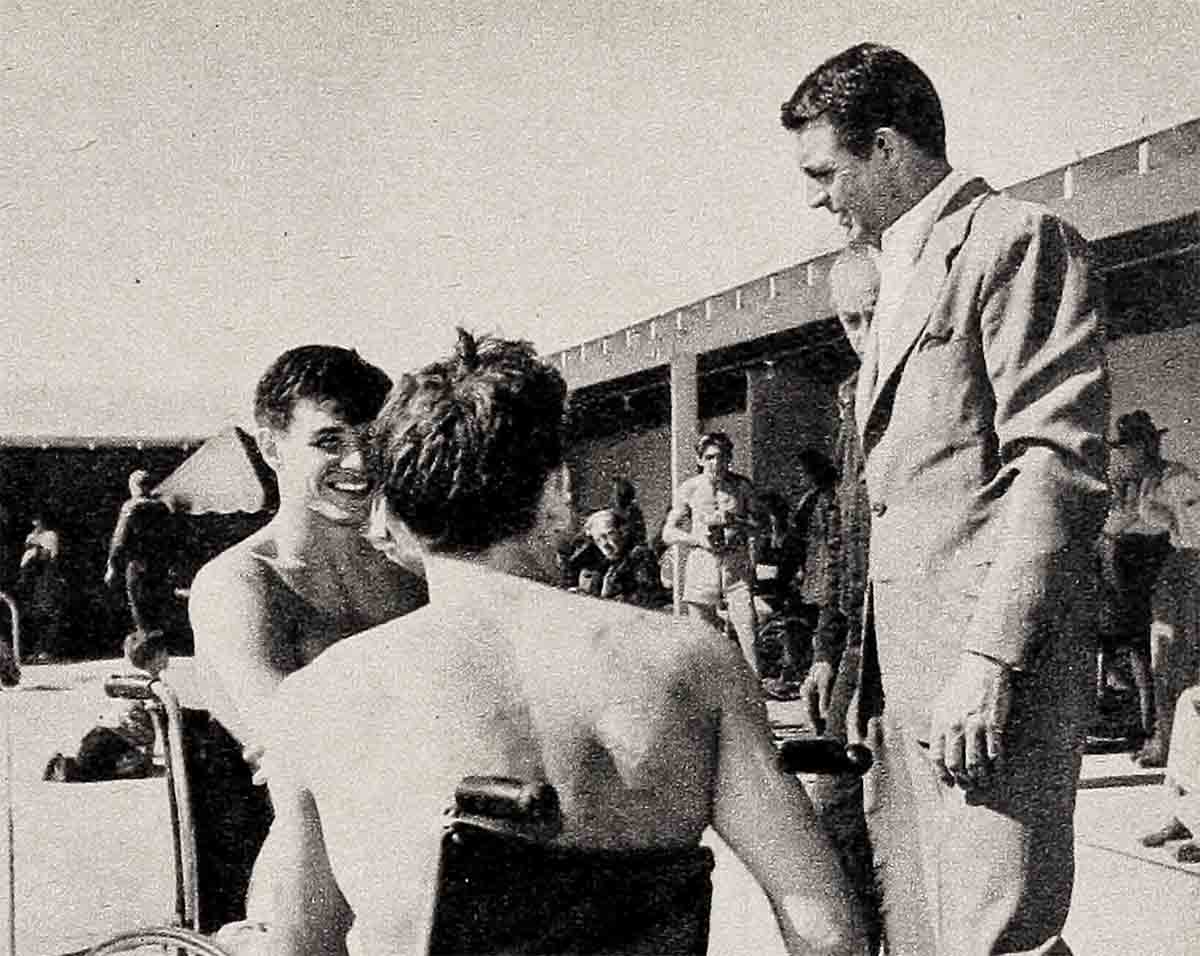

It’s still “V. J.” Day at Birmingham when Van drives over, but now he drops in as a friend, and not a stranger.

There are other stars who are keeping up their wartime habit of going out to Birmingham, although it’s been changed from an army debarkation to a veterans’ hospital. The six hundred vets that Van and the other stars know best are the paraplegic and tubercular victims, about evenly divided in number. (Paraplegia is paralysis of the lower half of the body, from the waist down.) There are as many more patients, less seriously disabled, who form a shifting or transient group, being constantly replaced by others as they are cured and returned to civil life.

The boys at the hospital have their own ideas about the Hollywood stars who visit them. If a star comes out once, they accept it as Just a gesture and not much more. If he or she makes a second trip, they are pleased. But if the star continues to come out and see them, the visits begin to have real meaning. A friendship-is formed; the visits take on the significance of reunions.

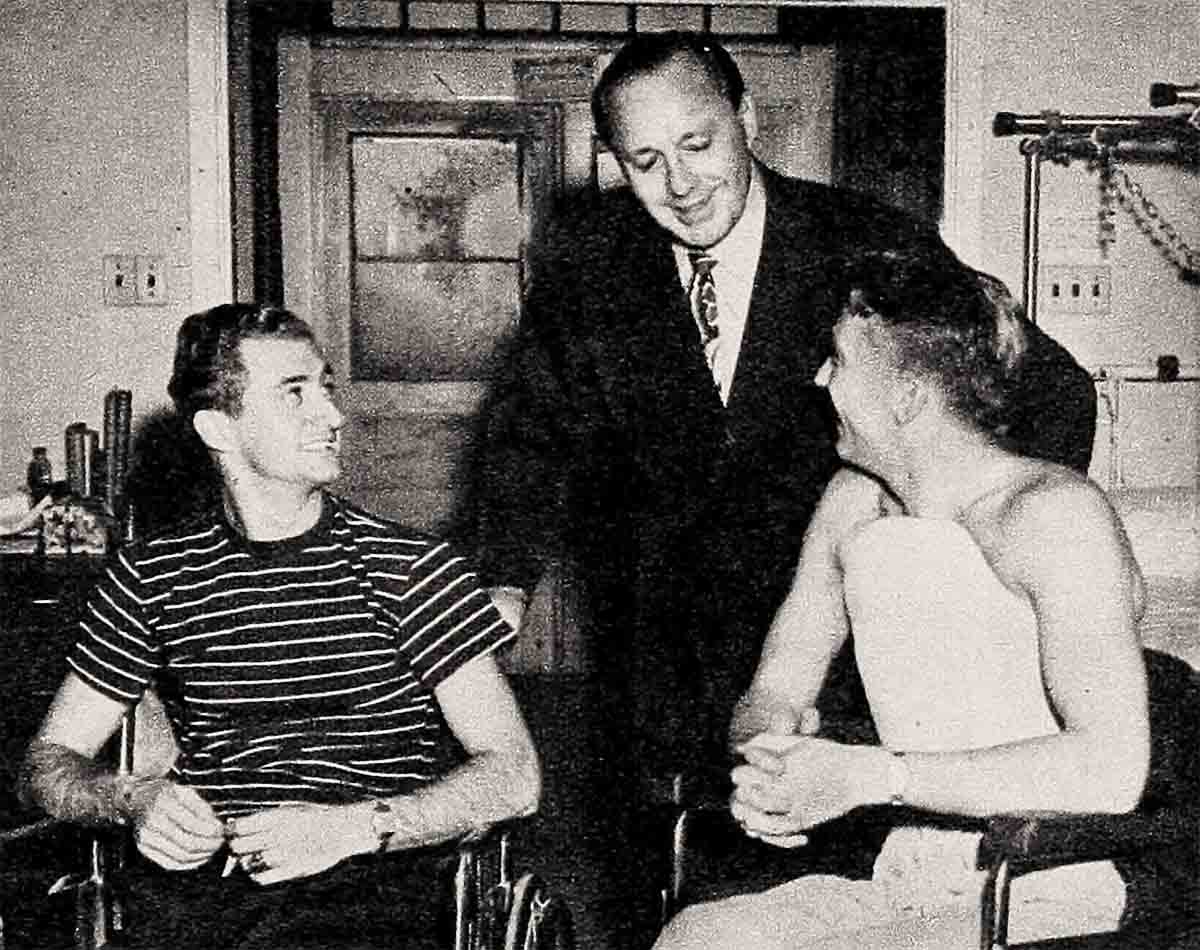

When Gregory Peck walks in, there are a hundred of the boys with whom he has formed associations. He knows the names of their whole families. He knows the color and style of their homes. They know Greg, and they know his wife, Greta. Many of them have been out to his home.

Take Janis Paige, of Warners, who comes out regularly with Don McGuire. A month ago she was kidding around in one of the wards when the doors flew open and in came a wheelchair vet carrying a big birthday cake. Nearly a year before Janis had happened to mention the date of her birthday. The boys had remembered.

Or think of Lou Costello crashing into a ward, waving his big cigar ahead of him and yelling, “What the. hell’s been goin’ on around here since I seen you guys last? Huh?” The latest thing Lou did was to get into an argument with a group of vets who were kidding him about the ability of his kid football team out at the Youth Foundation which he supports.

“Okay, you guys!” he yelped, finally. “I’ll bring the whole damn team out here, and another team for them to play, and we’ll see how good they are!”

He did just that. It didn’t settle the argument, which still goes on, but it’s strictly between old friends.

That goes for a lot of Hollywood’s famous names. For Susan Peters, herself a paraplegic as a result of her unfortunate accident, whose pet delight is to take a bunch of the boys fishing. Or for Desi Arnaz, who was stationed at the hospital as a sergeant during the war and never gets back to Hollywood but that he drives out to Birmingham to celebrate “Old Home Week.” Or for Bob Burns, Andy Devine, Don Ameche, who are neighbors, since they live near the hospital, and often drop in to meander around.

The hospital attaches still talk about Jose Iturbi who was asked to give a concert for the boys once. Great preparations were made for it and the piano placed on the stage of the recreation theater where all could see and hear. Iturbi gave his concert but he didn’t seem too pleased.

Not long afterward, he phoned the hospital and said he would like to come out the next day.

“But Mr. Iturbi, we’re not prepared to make the arrangements that quickly,” the special service representative protested.

“No, no,” came back Iturbi. “I don’t want to give a show. I want to play for the boys I know. I want to just drop in and play. Like you visit somebody, see?”

And drop in he did. And he has dropped in often; never giving any notice, never desiring a formal concert atmosphere, and forbidding any publicity about it. There isn’t any argument about it; he likes to drop in and play.

casual cary . . .

Cary Grant doesn’t even bother to phone. If he has finished a picture and has time on his hands, he simply shows up. He breezes into a ward, renews old acquaintances and has as great a time as the vets.

While Van Johnson is the old faithful of the boys, the “model” visitor is perhaps Olivia De Havilland. She established her technique on the first day she came. She was told that by confining herself to speaking a few words at each bedside, she could go through from ten to sixteen wards before it was time to leave. Olivia nodded and entered the ward. She went to the first bed and began talking. In a few minutes she sat down beside the bed, still talking to the soldier. Fifteen minutes later she was still there. When “chow call” sounded hours later, Olivia, instead of doing sixteen wards, hadn’t even finished one!

“Miss De Havilland,” said one of the nurses, “you’re making a wonderful visit with each of the boys but you’ll never get through all the wards this way.”

“Oh, yes I will,” said Olivia. “I’m off every Tuesday. I’ll come back.”

“But it will take ten Tuesdays to finish.”

“At least that,” said Olivia, and for the next ten Tuesdays she was back.

If you are a movie star, particularly a male, it is not the easiest thing in the world to walk into a ward and face two long rows of badly war-wounded men. There is an emotional interplay of such feelings as resentment and envy, and you are aware of it. It can be controlled and eliminated if you’re a nice guy and can show it.

When hospital visiting first began at Birmingham some stars made grand entrances into each ward. It was a mistake which resulted in every soldier instantly freezing stiff. Nowadays, the visiting star, unless he’s an old friend of the boys, slips into the ward quietly and is talking to the first veteran before any of the others are even aware of his presence.

Not all visitors to Birmingham are stars. One day, the hospital got a phone call from a chap who said his name was Malcolm Beelby; he was a staff musician at Warner Brothers. He wanted to come out and play the piano for the soldiers in the “closed wards.” These contain the mentally deranged veterans whom none but near relatives ever visit ordinarily.

music for the soul . . .

Malcolm, a young vet himself, can ramble on for hours through classics or swing numbers with equal facility. One afternoon a piano was rolled into one of the closed wards—they are not quiet places, as can be imagined—and Malcolm sat down to play. At once, a few of the men retreated from the music and were led away by attendants. The rest seemed not to notice it at first. One of these was a youngster who was the victim of a laughing mania, and was actually in such a fit now.

Malcolm played on. The men grew quieter. Some began to gather closer to the music. Fifteen minutes after Malcolm had started to play, the boy who was laughing stopped. His face bore a look of relaxation that doctors had been trying to induce ever since his admission into the hospital.

Toward the end of the session, Malcolm had a perfectly quiet and attentive audience. The medical men begged him to come back, and he’s now one of the hospital’s most appreciated visitors.

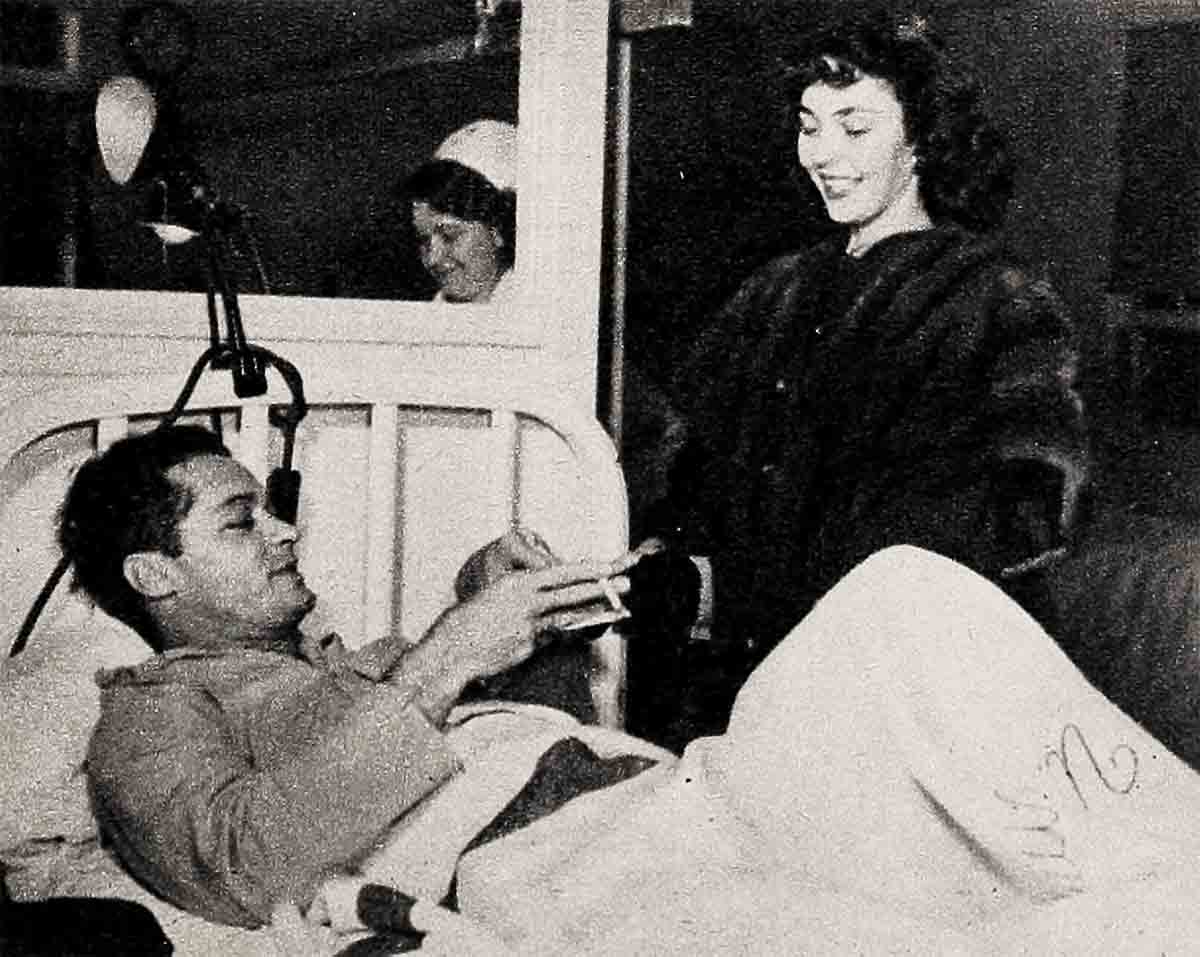

Most of the stars come out on Tuesday and Saturday afternoons, when the Volunteer Army Canteen Service holds its. parties, and distributes cigarettes. If you pass a ward and hear whistles, you can be sure Jane Russell has dropped in to say hello. Or you might catch Eddie Cantor singing to the music of a midget piano that he rolls around with him.

Remember when Bob Hope’s book, “So This Is Peace?” came out? He brought a ease of the books to Birmingham and handed them out after autographing each copy. Bing Crosby wandered into the hospital during the afternoon, and promptly accused Bob of peddling the books from bed to bed!

There are formal parties, like the last Christmas affair when the ‘hospital had four Santa Clauses: Guy Kibbee, Chill Wills, Bill Bendix and Harry Von Zell. They cruised the wards distributing gifts and then all came together for a super party in the recreation hall.

There are even more significant parties, including those held to celebrate the weddings which have taken place in the past few years between thirty paraplegic patients and their nurses.

And when it is a case of a party being thrown in the home of a star, it must be remembered that many patients make the trip all by themselves in their own cars. As a result of the hospital’s rehabilitation training, a paraplegic can wheel his chair to his specially built car (all hand operated), lift himself into the driver’s seat, and lift his wheelchair in beside him.

The stars have figured in this rehabilitation program. As head of the Hollywood Canteen Foundation, Bette Davis has seen to it that the boys received a $25,000 swimming pool, a battery of electric typewriters, and mimeograph machines for their newspaper. One of her personal gifts is her entire stamp collection, contained in a number of heavy, bound volumes.

There is a fine silver workshop in the hospital with full equipment for this craft. It belonged to Russell Gleason, who died in an accident a few years ago. His father, Jimmy, donated it. And to train the boys who want to learn silverworking, he induced one of Hollywood’s finest silversmiths, Alan Adler, who has a shop on the Strip, to come out twice weekly and teach.

And then there is Atwater Kent, of course, who has given nearly two thousand small, dis-assembled radios, which vets can put together and keep.

And always, there’s the guy they all dote on—the freckled “V. J.” himself.

Van has brought “V. J.” Day to hospitals, soldiers, and even civilians, all over the country.

On a recent trip to Memphis, he had just 28 hours to spend in town. During this time, he was booked to make four theater appearances, three radio broadcasts, and to take part in a half-dozen newspaper interviews. He raced through them so that he could go out to the Kennedy Veterans’ Hospital there, for which he managed to find two full hours.

Around the studio, his faithfulness to his friends and acquaintances is amazing. Two years ago, the head of the portrait photographers, Milton Brown, was stricken with a heart attack. He was in the hospital for three months. Naturally, during his first week there, his friends sent flowers, came out to see him.

But there was an end to that after a while, and he was alone, looking forward to months of loneliness, and boredom. That’s when Van showed up. He walked in with an armful of flowers and presents promptly at seven o’clock one evening, and stayed until visiting hours were over. That’s not unusual. But consider this: twice a week, for the full three months that Milton was laid up, Van showed, as regular as clockwork!

Sometime after Milton was discharged from the hospital, he suffered a relapse and had to go back for three and a half more months. Van was on the job immediately.

Not a soul at M-G-M knew about this, and it would never have come to be written here if Milton Brown hadn’t forgotten Van’s warning to keep quiet. Van, like Iturbi about his piano parties, is dead set against any publicity. It is only because you can’t gag a whole staff of nurses and copter, that his kindness becomes known at all.

One evening, a doctor at Birmingham walked out to his car and found it was blocked by one of those big trailer trucks. Just then the owner of the car next to his came out.

“Oh, Lord!” said the doctor wearily. “I suppose I’ll have to run back and locate the driver of that truck. He might be anywhere in the hospital.”

“Don’t do that, doc,” said the other man. “You’re tired. I’ll move the truck for you.”

“You?” asked the physician. “You’ve spent all day walking through the wards. You must be as tired as I am.”

“Naw,” said the other. “Besides, I’m a truck-driver at heart.”

He jumped into the cab of the big ten-wheeler and started the motor immediately. Skillfully, he backed it clear and let the doctor pull out. Then he rolled the truck into the vacated space, shut off the motor and got into his own car.

It’s only natural, isn’t it, that that doctor would mention what happened, to his friends. And that the young fellow who went to such trouble so cheerfully should have been old “V. J.” Day Van, himself?

THE END

—BY HANK JEFFRIES

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948