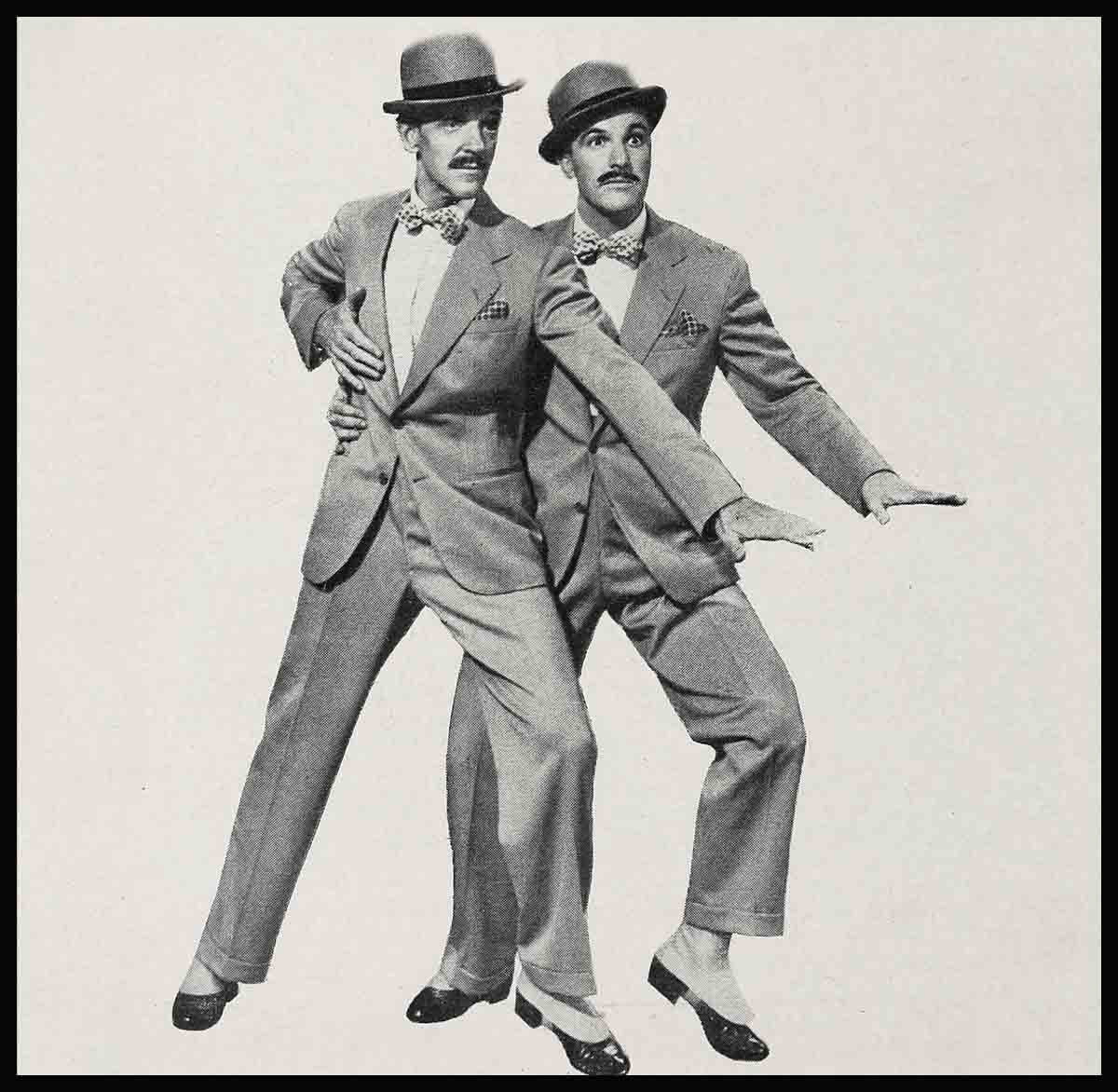

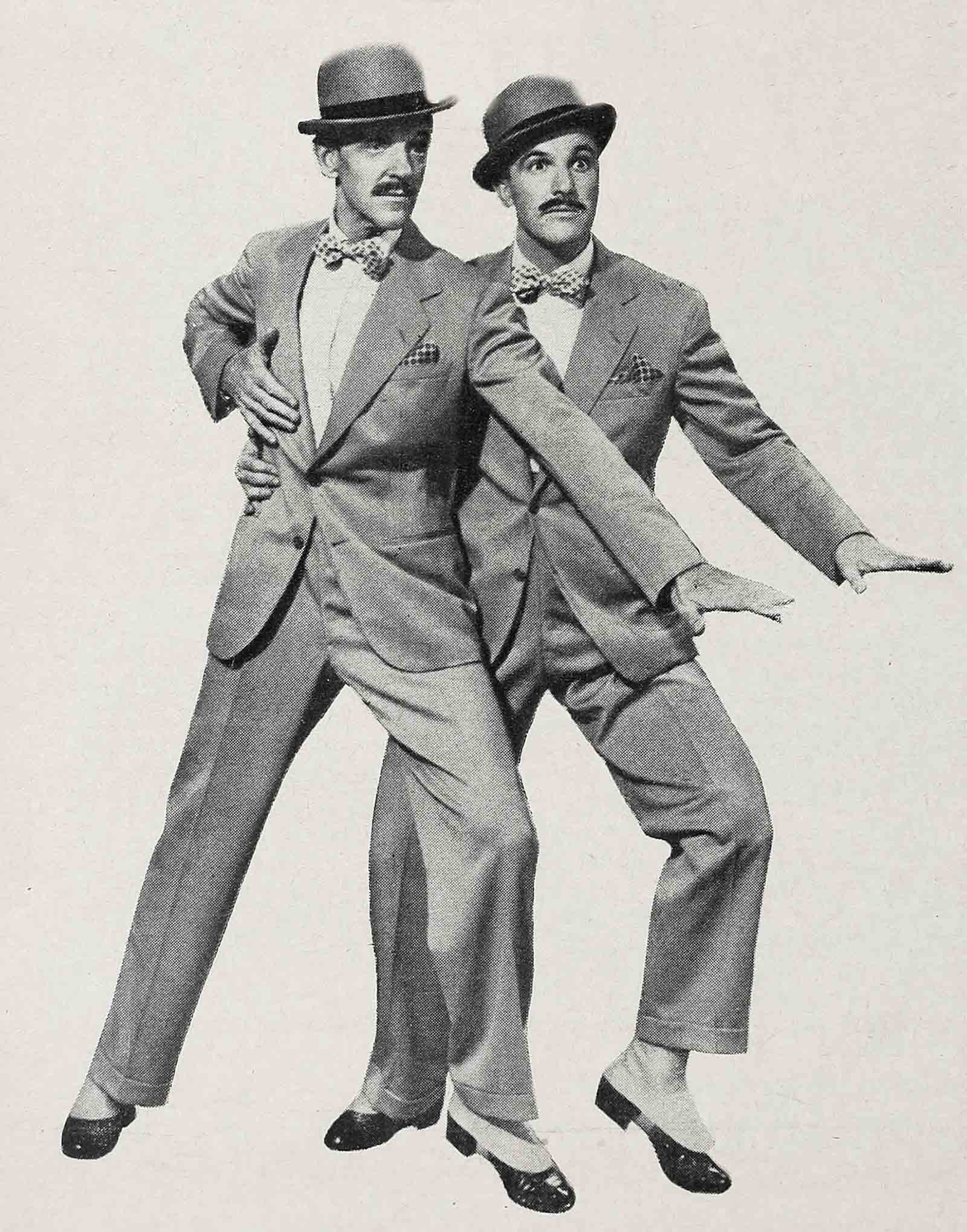

Tough Break, Gene!

I was sitting on a terrace in Hollywood, wearing a pair of shorts and a sweater, my feet up on a table, a glass in my hand, a copy of the Los Angeles Times spread out on my lap (open

at the comic section) when I was called to the phone. It was a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer executive, and he said, “Fred, Gene Kelly’s broken his ankle. Will you come over here and take his spot in Easter Parade?”

“Oh now wait,” I began, but he wouldn’t let me finish.

“The picture’s all set up, the cast is ready, the sets are designed—we’re really in a spot.”

“I’ve retired,” I said.

“Hoofers never retire.”

“But what about Gene?”

The executive made a number of inarticulate but alarming noises. “All right,” I said hastily. “I’ll come over and look at the script and well talk about it.”

We talked about it all afternoon. Then I went to see Gene.

“Just how bad is this thing?” I asked him. “Couldn’t you be ready in a month, two months?”

“I won’t dance again for five months.”

“But they could postpone the picture.”

He said, “Fred, I really mean this. It’s a good picture, and you’re right for it. If you bow out, my accident means trouble for the studio. If you take the part, everybody will be happy, including me. How about it?”

“To tell you the truth, I’ll be delighted,” I said, and that was the truth. When I had announced my retirement a year before, I had never meant anything more sincerely in my life. I had been dancing professionally for more years than I liked to remember, and I was tired. I found myself, at the completion of each new number, thinking: “This is it. This is the best you’ve done, and the best you can do. You can’t keep topping yourself forever, and yet, if you don’t, the public will get wise to the fact that you’re levelling off. Now is the time to quit, before people begin asking you to.”

So I went back to our home in the East, and began relaxing. It was wonderful, for a few months. Then one morning my daughter, who is four, said at breakfast, “When is Daddy going back to the studio?” I didn’t even know she understood what the word meant. She had been brought to a studio to visit me just once, a year before, and apparently the experience had impressed her deeply.

A few weeks later, I dropped in at the school in Aiken, South Carolina, where my son is a student. Fred is eleven; and has the modern boy’s sharpness of wit and tongue. “What are you going to do, Dad?” he asked directly. “Retire?” It occurred to me for the first time, then, that my work meant something to him, that he considered it important for his father to be an active, functioning human being, instead of a has-been.

Even the critics, upon hearing the word “retirement,” suddenly decided I was better than they had ever thought before, and said so in print. Also, to my intense astonishment, they said so in personal letters to me.

I came back to Hollywood. I discussed making another picture with Ginger Rogers. I wanted to be in again—but not at the expense of another dancer, not to profit by another chap’s misfortune. Gene cleared that up with one of the nicest remarks I have ever heard in such circumstances. He said to a columnist, “Naturally, I hated to break my ankle, but if it means seeing Astaire on the screen again, it’s worth it.”

There is a gentleman. There is also one of the finest dancers in America today.

An accident such as he suffered is not just a casual misfortune. To a dancer, anything that disables or even impairs him physically, if only temporarily, smacks of tragedy. Twice it has happened to me, and I know.

The first time was in 1919. I was playing in Apple Blossoms, dancing to Fritz Kreisler’s enchanting score, and we were opening in Providence, Rhode Island, before one of the toughest audiences in America. Everyone in the cast knew just how tough it was, and prepared to strip his gears to put the show over. I was fresh to show business at the time, imbued with the spirit of the evening. I knocked myself out, figuratively and almost literally.

My most difficult turn was performed on a stairway—always dangerous—and at the end of the number I did a series of fast twist steps, then grasped myself by my shoulders and did a spiral full turn into a squatting position; since my feet remained stationary, I finished with my legs crossed, like an Indian at a conference.

I performed this finale that evening with such vigor that, as I landed in the tag position, there was a small sharp report and my sacro-iliac went away somewhere. I managed to finish the show, but later in my dressing room I lay down for what I thought would be a few minutes. I did not get up again, under my own power.

For ten years, I couldn’t walk down the street or play tennis or dance without knowing that at any moment I might lose control of my feet, and face a long siege of pain and helplessness.

The other accident served me in good stead, though at the time, I cursed fate. I was dancing with my sister, Adele, and I went in a good deal for high kicking; once, while my right foot remained several inches above my head, the other ankle turned, and I went sprawling into a heap. That sprain put an end to the high kicks, and incidentally, improved my work, since I had to substitute less corny and spectacular—but more subtle and interesting—devices.

Fred Stone, who was once a famous dancer before he became a theater great, took up flying, crashed, and did not dance at all after that. Thank God, Gene’s injury will not mean the end of dancing for him. He broke the same ankle once before, in the same kind of accident, and his doctors tell him that it will heal in the same fashion. I say “Thank God,” fervently, because I can think of no greater loss to the American stage and screen than if Gene Kelly should not dance again.

I shan’t soon forget the first time I saw him, in Cover Girl. When Gene did his Alter Ego number I realized that I was watching an artist. I grabbed my wife’s hand. “Look!” I said. “Look at that!”

She maintained a loyal silence.

And when I saw his inspired cartoon sequence in Anchors Aweigh, I knew. Gene’s technique was not only superb; he had imagination and a genius for producing.

It is one thing to dance flawlessly through a piece of-music. It is another to take an idea, a mood, and interpret it in terms of rhythm and movement so that an audience discovers what that idea is without hearing a word or reading a line.

Gene’s ingenuity is boundless. There have been times when I have known in advance the interpretations Gene would be asked to invent in certain scripts, and I have asked myself, “How would I do that?” On a number of occasions I have had to admit to myself, “I don’t know.”

Then, when I see what he has created in the finished product, I am aware that I am watching, not my greatest rival—although he would be that if we were in competition—but a contemporary whom I regard with respect’ and admiration.

This is a calculated personal appraisal of Gene’s ability, and if it sounds like a back-patting spree I can’t help it. Just thank your lucky stars that he’ll be back with you in a few months, while I thank mine that I’m back where I belong, on a sound stage.

THE END

—BY FRED ASTAIRE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948