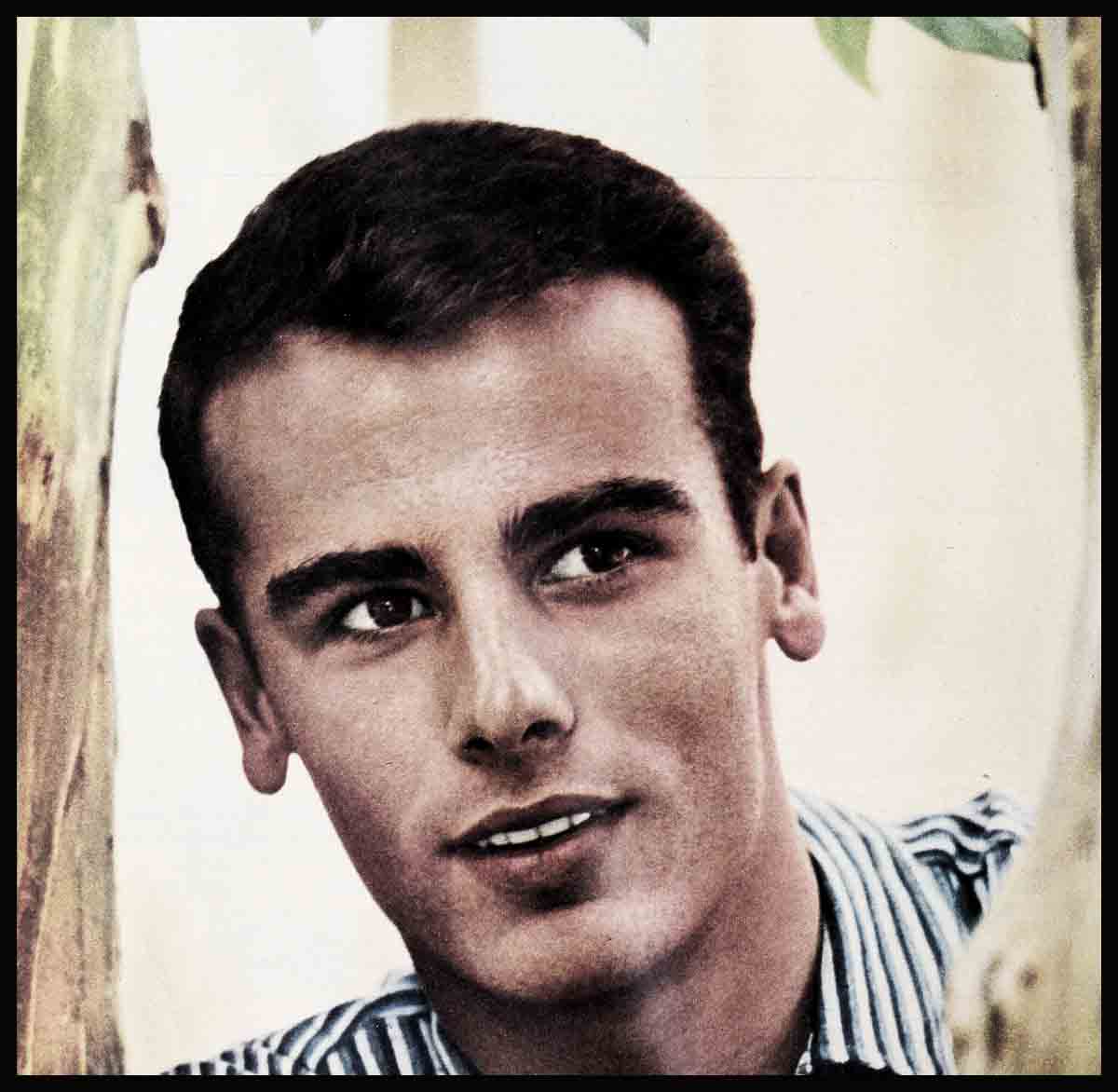

A Handful Of Quarters—Dean Stockwell

When I was thirteen years old, something happened that I’ll never forget. I believe it was the most important thing that ever happened to me. And I don’t think this feeling I have about it will ever change, although I’m only twenty-one now.

It’s a strange thing, hard to explain. I’m not sure yet that I completely understand it. But I can see now that life, especially for a teenager, is made of such incidents that touch us, and change and mold us.

I had gone to the Los Angeles YMCA that afternoon, and I was playing ping pong with one of the boys. I got a kick out of ping pong and tennis—tennis is still my favorite sport. I was having a great time, batting the ball back and forth, and I didn’t notice at first when a boy I knew slightly came in, and walked over to the billiard table.

Suddenly, there was a lot of yelling and rushing to the table, and I turned around to see what the excitement was about. The boy was standing there, throwing quarters on the table! I ran over as fast as I could, scrambling and pushing my way in with the rest of the mob. There must have been about five dollars’ worth of quarters on that table. That was a lot of money to me. Sure, I’d been working steadily as a child actor. But a lot of my earnings were kept by the court until I came of age. And my mother had quite a struggle to support me and my brother Guy ever since she and my father separated when I was five. Quarters for spending money were something special.

I reached out for a handful of those shiny quarters. Then, something made me stop. I looked up at the boy who was standing there throwing them, and I let the quarters fall back on the table. My arms fell to my side, and I drew back, just staring at the scene—the grasping, shouting boys, acting like greedy animals at the sight of the money, the boy who was throwing them expressionless, with no joy in what he was doing. There was something defiant and contemptuous about him, something very sad and very lonely, too. But no joy. If he had been a rich boy, it wouldn’t have been so strange. But he wasn’t. I knew he was a kid who had a very tough life. He was only about fifteen, but he looked much older. He lived alone and made his living from a newspaper route. He sent money to his folks, too, the fellows said.

Why did he do this crazy thing? Was he trying to buy recognition and friendship that he didn’t have? Was it a gesture of frustration and defiance, directed at the thing that had made his life miserable—lack of money? Was he getting some kind of bitter satisfaction in seeing the others act like little monsters? I still don’t know.

But one thing I do know—the reason that incident is so significant to me. That was the day I started to think.

I know that this awareness of life and its meaning, this beginning of finding the answers to the questions, “Who am I?” “What am I going to do with my life?” “What does life mean?” is something that comes to every teenager, in varying degrees. It is not a happy state. It can be pretty painful.

Many people say that the teenage years are the happiest. They think of them as being carefree, full of fun. I don’t agree. I don’t think that any years are the best, or the worst. Every year brings its own problems.

I certainly wouldn’t be so presumptuous as to set myself up as a spokesman on teenage problems. I don’t feel that I have the maturity or experience for that. I’m still trying to find the answers. All I can do is speak from my own experience, as a person, and of what I have learned from study, and from some of the roles I’ve played.

I was always a loner. Even as a baby, my mother says, I was perfectly happy when I was by myself. So, when I became a child actor and got my schooling from a studio tutor instead of in a regular school with other children, I didn’t feel deprived. In fact, I had some wonderful teachers who gave me much more personal attention than I would have had elsewhere. And I had a wonderful home life. My mother did everything possible to give my brother Guy and me a happy childhood, and we were very close. Guy is two years older than I, and took the place of the playmates I didn’t have. He’s married now, lives in Oakland and has two children, but we’re still very close. I remember being a bit envious of Guy when my mother bought him a horse, even though he let me ride it. I realize now that it was a wise move on her part. It was at the time when people made a big fuss over me because I was in movies, and she wanted to make it up to Guy.

But the fuss that he envied was something I never liked. It made me feel uncomfortable, like some kind of curiosity. I never “fitted in.” I never “belonged.” I was Dean Stockwell, child movie actor. It was like some kind of label. The boy, Dean Stockwell, was somebody no one knew or cared about—except my mother and Guy.

That was the tough part. The work— well, that I just accepted as something that had to be done. I simply did what I was told, and that was that.

It wasn’t until I reached my teens and left the studio tutors to go to parochial school for two years, then to public high school for my last year, that I realized just how much I didn’t “belong.” I hated it! Oh, there were some nice girls and fellows who accepted me as one of them, but for the most part, my brand as a child actor was a barrier that made it impossible for me to be accepted. So I never took part in any school activities. I played a little tennis, but that was all.

And those schools! I suppose that’s a problem that many teenagers have today. The teachers were underpaid, and the school overcrowded. Many of the teachers, possibly because of the low pay, were indifferent to the students’ needs, and some totally unqualified, even from the standpoint of knowledge. There wasn’t time for any personal attention. And people wonder why some teenagers don’t like school, or get into trouble!

Take me, for instance. Ever since that day when I was thirteen and walked out of that YMCA, I had a great desire to learn, not only from books, but about life. But that need—which Im sure is shared by other young people—was never met at the school, where it should have been. I was lucky to have a good home life. But what happens to all the others who don’t?

When I got out of high school, I was more at a loss than ever. I knew there must be some way to end my confusion, to help me find myself. But I didn’t know what. I was pretty miserable.

My work was still just that—work. When M-G-M dropped me, I didn’t feel bad about it. And when they called me back for another picture, shortly after that, and I got offers from other studios, I wasn’t overjoyed, either. At that point, I just didn’t care.

More and more, I felt that the thing to do was to get away, to go to some place where I wasn’t known as Dean Stockwell, Child Actor. I could have gone on working in movies—but that could only mean going on being miserable. So I told my mother I was quitting, because I wanted to go to Berkeley to college.

I hadn’t the slightest notion about what to expect from college and, maybe, it’s just as well. Because what I got was a little knowledge of psychology from the courses I took, a lot of knowledge about poker and bridge, and some knowledge about girls.

I’d never dated much—back home, I had the same old problem with girls who looked at me as an actor, not just another guy. Besides, I never liked the kind of dates where you go through all the rigmarole of dressing up, calling for the girl with flowers, going to some show or night club just for the sake of going somewhere, I still don’t. I didn’t like parties, either. Something in me still revolts at the prospect of a lot of people sitting around making small talk that means nothing, and I know I’m likely to behave boorishly, so I don’t go.

One college experience I had certainly strengthened my feelings about that. There was a big formal college dance. I didn’t have a date, there was a girl nobody had asked, so our friends paired us off. It was pretty sad. She was a nice enough girl, and maybe under different circumstances we might have enjoyed ourselves, but we were both so conscious of the way we’d met that it was impossible. We tried dancing, but neither of us were much good at it. Then, two by two, the couples started leaving. We found out some guys had en a room in a hotel across the street and had a lot of liquor there. Everybody was over there getting stewed, while the beaming housemothers on watch at the dance didn’t suspect a thing. Some party!

At the end of my first year, I decided college was not for me. But please don’t get me wrong. I’m not against college. I simply didn’t find what I wanted there, possibly because I still wasn’t sure myself what I wanted. But I did gain a lot from the experience. The greatest thing about it, for me, was a wonderful sense of freedom. For the first time, I was able to get away from my child actor tag and be just another fellow. I could make friends and date girls. And for the first time, I got away from the sheltered familiarity of my home and the studio and learned something about life, by mixing with fellows and girls whose backgrounds were much different from my own.

I know that there are a lot of fellows, and girls, too, who go to school, get married and settle down in a comfortable groove and seem quite happy about it. But I think they miss a lot. How much can you feel and appreciate in your own life, if you know nothing of the lives of others? For this reason alone, I think a teenager can get a great deal out of going away to college. I know I did.

But it wasn’t enough. I was at loose ends B again—but now, there was a difference. I knew what I wanted to do. I was going to go out in the country, traveling and working at whatever jobs I could find, to learn through living, and seeing how others lived.

When I told my mother this, she wasn’t too happy about it. I guess all mothers worry about their kids going out on their own. But she was great. She understood why I had to do it, and she never tried to stop me.

Exactly what happened during those three years when I was away from Hollywood, I don’t care to say. These memories are something that I want to keep for myself, as one part of my life that belongs just to me. Besides, what happened isn’t so important as what I learned from this experience.

When I set out, I had no money with me. I worked my way, as I had planned, and though I didn’t leave the country, I traveled all over the United States.

Did I find what I was seeking? Definitely, yes! Not only from my own experience, but from observation. I saw how other people felt, and acted and thought. And I learned a great deal from it. In short, it was an education in living.

I’m not suggesting that every teenager hit the road, as I did. Because of my problem of being identified as an actor in Hollywood, I was shut off from many normal contacts, and mine was a special case. But I do strongly believe that every young person, particularly those who are confused and uncertain about the future, should get out and mix with others, to find out how other people live. Only in this way can you hope to understand yourself.

When I felt that I had gotten enough from my wanderings and it was time to get down to the serious business of building my life, I came back to Hollywood, to the only work I knew—acting. But what a difference! My eyes had been opened. Acting wasn’t just a job anymore; it was a complicated, difficult art—a real challenge.

Frankly, I’ve found so many interests that I’m still not sure I want to be an actor. But I do find it exciting. After I finished “The Careless Years” for United Artists, I came to Broadway to play the role of Chuck Steiner in “Compulsion.” This part fascinates me. The play is based on the novel, which was inspired by the famous Loeb-Leopold case. Mine is the Leopold part, and Roddy McDowall plays the Loeb part. Now, at last, I know how interesting acting can be!

One thing about my return to acting was embarrassing—and totally unexpected. That was the business of my being compared to Jimmy Dean. It happens that fast sport cars are a weakness of mine. I love to drive by myself for miles because it’s a good way to get a change from the pressures and petty details of everyday routine and clear your thoughts. Unluckily, I bought a Porsche. I didn’t know Jimmy owned one, in fact, I didn’t know Jimmy, and since I’d been away. I knew little about him. Before I knew what was going on, I was accused of imitating him! I’d like to make it clear that I never intended it. I don’t think imitation is good for anyone. You’ve got to find your own self.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t have all the answers. I’m still looking for them. All I can say to other kids who have trouble understanding life and themselves—they have a lot of company and there are no short cuts, no easy way. Growing up is something that comes gradually, through experience and development. Reading and music helped me find myself.

And one thing I’ve really learned—finding a personal philosophy can really brine more happiness than anything else. That’s why I’m glad about that handful of quarters. They made me start to think. I hope I never stop.

THE END

—BY DEAN STOCKWELL as told to INA STEINHAUSE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957

gralion torile

11 Ağustos 2023I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one these days..