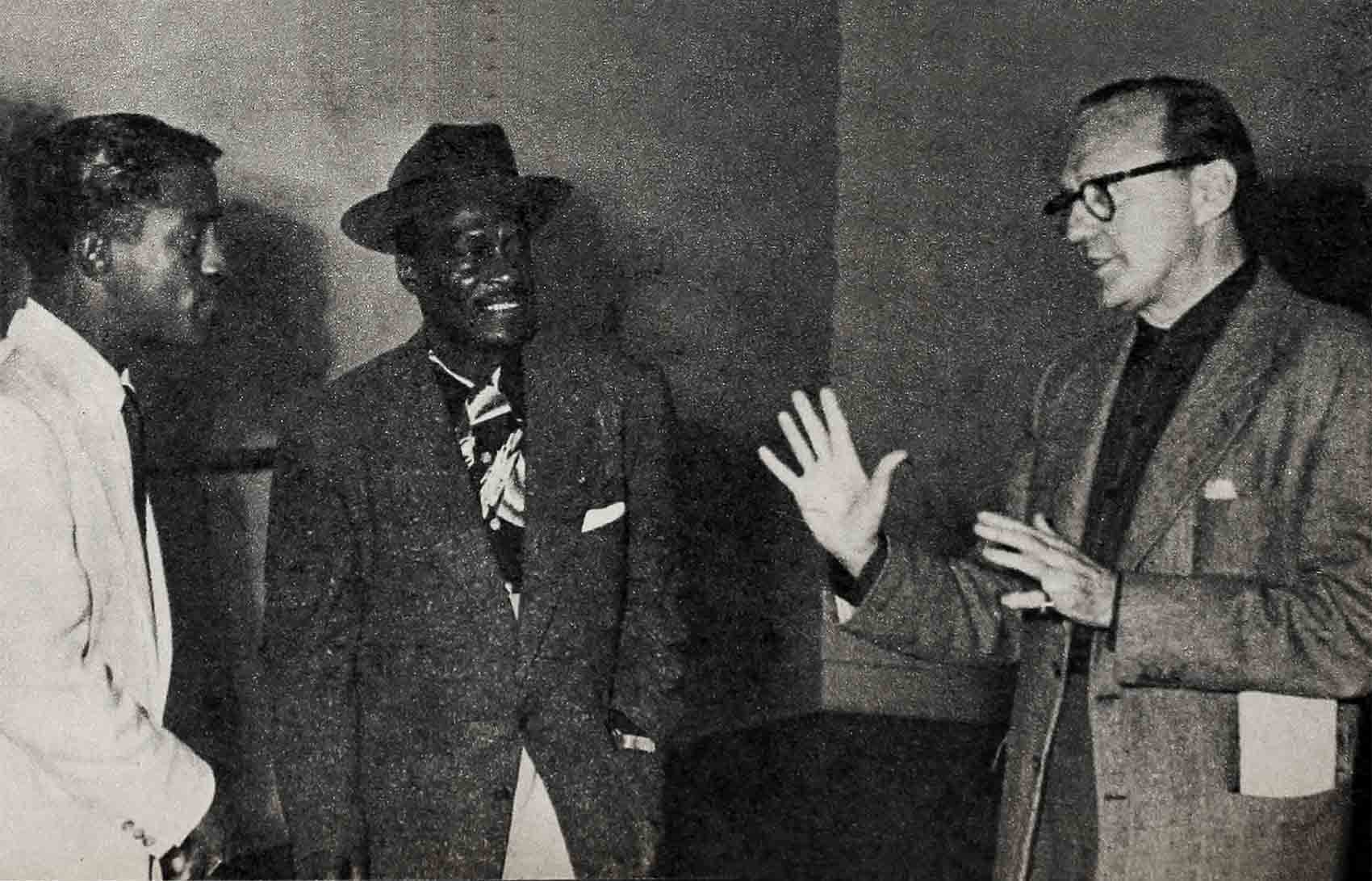

The Sammy Davis, Jr., Story

This is not, in the traditional sense of the words, a Thanksgiving story. It has nothing to do with the Pilgrim Fathers, nothing to do with harvested crops, turkey dinners or family life. It is not what you expect to read about on the fourth Thursday in November. But in a deeper sense it is a Thanksgiving story of the oldest and the most hallowed sort. For it is the story of a man who was forced suddenly to pause for the counting of his blessings and the reckoning of his friends. It is the story of a man who took stock of his life and learned, in an hour of shame and fear, just how very much he had, after all, to be thankful for. . . .

It is the story of Sammy Davis, Jr., and of the town that suddenly seemed to remember that he was a Negro.

It was cool and brisk when Sammy Davis, Jr. walked out of the Moulin Rouge and into the late night air. His last show had ended around two; it had been a good audience and they kept him coming back for more and more songs until his tired throat just couldn’t sing another note.

He finally raised his hands in a happy, weary gesture of good-bye. “Come back tomorrow night,” he told his audience and they had laughed and given him a final burst of applause before they began to straggle home. Now, tired and content, he was leaving, too—but not for home.

Dean Martin was giving a party at his house, and Sammy had promised to be there, no matter how late. For a moment, breathing in the crisp fresh air, he thought of not going—of taking a long walk home, of getting some sleep for once. Then he shrugged and grinned. Sleep could wait—his friends couldn’t. Besides, the best tonic for him had always been a good time with nice people. It would relax him, refresh him, take his mind off his troubles. For a couple of hours he would laugh and talk and forget to worry about the movie he had just finished, Anna Lucasta . . . and the one he wanted so desperately to make, was going to talk to Sam Goldwyn about tomorrow—Porgy and Bess. He’d forget about his separation from his wife, about the pressure of two shows nightly—he’d simmer down and enjoy himself.

Happily, he drove through the deserted streets to Dean’s house.

The party was still in full swing when he got there. Hollywood parties usually began late and ended early—early in the morning. Now this party was getting to that time when everyone in the room was getting up to do something—sing, ham up a dance, tell a few jokes. For most of them it was the best part of a get-together, the time when they did their stuff for the hardest and best audience of all—show people. A well-known comedian, a good friend of Sammy’s, had the floor when Sammy walked in; he had already pulled Gordon MacRae and Jimmy Durante up to the front of the living room for a song; and now he was launching into his own act—jokes and patter and a quick exchange of friendly insults with the laughing audience. Sammy stood for a moment at the entrance, getting his bearings. A head turned, someone noticed him.

“Hi, Sammy!”

Instantly, other faces turned to him, other voices called out. Up front the man with the jokes broke off a word, glanced over. Sammy put his finger to his lips, nodded to his pals, and started to tiptoe across the floor to Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh.

“Black and White”

He was halfway there when the comedian spoke up. “Sammy, shut up. I don’t like a performer to be on when he’s not on.”

For an instant Sammy’s jaw actually dropped with surprise. Then he shut his mouth firmly. Don’t be an idiot, he told himself. He’s just doing his act. You’re being over-sensitive again, boy.

He went on picking his way across the room. Tony had his hand stretched out in greeting. Sammy reached out his own.

“Sammy, shut up!” There it was again. This time he couldn’t help himself. His head jerked up. “I haven’t said a word,” he started to protest. But he didn’t get the words out. reached out for him, pulled him up front. For an insant he held Sammy there, cheek to cheek. “Black and White,” he quipped—and waited for his laugh.

It didn’t come.

In the silence, the dead, awful silence, Sammy felt his heart turn over. From far away somewhere a piece of his mind whispered, Make it a joke. Make it a joke. . . . He heard his own voice saying loudly, “Say, when I leave, someone please send for Mr. Lincoln.” Dimly, he heard the faint, embarrassed laugh from out front. And then somehow, he was sitting down again with Tony and people were talking to him and an hour later Frank Sinatra was telling him to sing: “You close the show, Sammy. Nobody here has the guts to follow a guy with your talent. . . .” And so, of course, he was up front again, singing this time, and smiling.

And all the while, his mind was whirling and a voice was repeating over and over and over again: Why, why, why? I thought he was a friend of mine. Why did he do it? What does it mean? Are they all thinking it behind their smiles, that I’m black and they’re white? After all this time—is that what it comes down to after all? They’re white. I’m black. . . .

This voice went on whispering long after Sammy had said good-night to Dean and his wife. It whispered in his ear through the long drive to his place in Hollywood Hills; it kept him lying awake through the grey dawn.

Was it possible? His friends—they had to be his friends. After all the years they had known each other, worked together, eaten and partied and visited together. It couldn’t have been all a lie. And yet. . . .

And yet—he had thought this comedian -and his wife were his friends, too.

His pal Frankie

The sun came up over the hills. Bleary-eyed, unable to sleep, Sammy got up and put on a robe. He had to remember. He had to know. . . .

And of course, the first guy who came to mind—was Frankie.

Frank Sinatra! Even through his fear, Sammy smiled remembering the first time he met ‘The Voice.’ That was in 1941. Frankie was with the Tommy Dorsey band; Sammy was part of a vaudeville act that played the same bill: Frankie was skinny even then, and getting skinnier. Sammy used to sit in his dressing room night after night and mutter, “I’ve got to try it on my own. I’ve got a beautiful wife; we’re going to have a baby. I’ve got to make it. I feel it. I’ve got to try. . . .”

That was in ’41. The only way Sammy Davis could get near Frank Sinatra was by bucking the mile-long lines to get into the Paramount Theater. Frankie had made it, all right. Then the Army gave a whistle, and for a few years Sammy had more to do than stand on movie lines. In 1945 he got out and the first place he and a buddy headed for was the Hollywood Canteen. Like a couple of teenagers, they hung around waiting for a glimpse of the movie stars, even wearing their uniforms an extra couple of weeks. Man, that was the life.

One night some guy let them into the Hit Parade show even though they didn’t have tickets. They sat in the sponsor’s booth, and all the way through Sammy made a dope of himself, nudging people and pointing to Sinatra. “I know him. Sure. I worked with him once. He wouldn’t remember, but—”

At the end of the broadcast, his buddy wanted to take off. Sammy hung back, watching Frankie sign autographs, joke with the kids. “Come on,” his buddy pleaded. “He won’t know you. What are you waiting for? Look who he is!”

Maybe it was the sound of his voice that caught Frankie’s ear. He turned around and took off his sun glasses and looked Sammy right in the face.

“I know you,” The Voice said slowly, “don’t I?”

Sammy was shaking with excitement. “Yeah. We—we worked together once.”

Frank nodded. “Sure. You look familiar to me, Charlie. . . .”

“No—my name—my name is Sammy.”

Frank shook his head. “I hate the name Sammy. I’ll call you Charlie.”

After that, twice a week there were a pair of tickets at the box office for ‘Charlie’. And after the show there would be a phone call from Frank. “How’s everything going? You like the show? You want to come to rehearsal? There are some people I’d like you to say hi to. . . .”

He never said a word about helping Sammy get back into show business. He didn’t have to say anything. He saw to it that he met everybody who might possibly be interested in a guy who could do impersonations and dance and sing up a him to Humphrey Bogart’s house and Judy Garland’s place—everywhere. Through the lean years he was always there with a good word and a big laugh and a sawbuck if a guy ran a little short of luxuries like food.

And when Sammy lost his eye, Frank had been there then too, with more than sympathy—he’d swept Sammy out of the hospital and off to Palm Springs to recuperate. He’d picked up the bill all right—that was a kindness for which Sammy had long since paid him back. But the bigger kindnesses—the companionship, the comfort, the hope he held out when life seemed impossible—those were the debts a man was proud to owe all his life to his friend.

No, Frankie couldn’t be prejudiced anywhere in his heart. He couldn’t.

His pal Tony

There had been Tony Curtis, too. There was a guy who had to like Sammy all the way. He had to. Why, Sammy had been one of the first to hear about Janet when Tony was dating her. He could still remember the look on Tony’s face when he drove up to Sammy’s place one night in the used Buick convertible he was buying with his first movie checks. He’d babbled all night in that Bronx accent he hadn’t gotten rid of yet: “Man I’ve been dating a chick that is the most wonderful girl in the world. I’ve been dating her too much, because I don’t make enough money to marry, you know? But she is everything. I’m young, Sammy, and just starting, and everyone says I shouldn’t marry. So I won’t. But man, she is—” And so on, right up to the night he eloped with Janet despite his age and his money troubles.

A guy wouldn’t talk to you about the woman he loved unless he really dug you, would he? He wouldn’t confide in you when all the time in his heart he thought you were dirt. . . .

But, then—last night . . . Sammy shook his head miserably. If only there were some way to know why that had happened to him. Why, he’d never had anything but the most courteous, the most generous treatment in the world before an audience. Like, for instance, his opening night at Ciro’s—the first time he had stepped into a spotlight with a patch over his eye and deathly fear in his heart. Would they hold still for him, a one-eyed colored man who had just barely begun to make a name for himself? Would the patch distract them so they wouldn’t listen, wouldn’t give him a chance? He was trembling with nerves; his face glistened with sweat as he walked out on stage.

And then—and then they had cheered. That whole roomful of people had stood up and cheered him till their voices were hoarse and their affection and admiration had seemed to enfold him in a pair of loving arms. His cheeks had been wet with something other than perspiration when the shouting finally died down and he began to sing.

His pal Jerry

And that wasn’t all, either. When he began to tire toward the end because of the excitement and the singing and the weakness he still had from the long weeks in the hospital, when his breath began to run out—Jerry Lewis had come climbing up over chairs and feet to join him on stage, to clown like nobody else in the world could do, to kibitz around to the delight of the audience till Sammy could get his wind again. The next day Jerry was fined $500 for it by the entertainers’ union, AGVA—it was against regulations for an artist to appear, unpaid, like that. So what happened? The night after, he came back again and did it all over. It cost him a thousand dollars to do a favor for a friend—and he did it with an open, loving heart.

Oh, there had been so many who had befriended him. Jack Benny, who used to buttonhole producers and talk to them about Sammy. Elvis Presley whom Sammy scarcely knew—he’d been thoughtful and interested when Sammy asked him how it was to work the South. “People are just people anywhere,” Elvis had said. “You’ve got good guys and bad guys all over. Me—I’ve got every record you’ve ever made, Sammy.” He’d invited Sammy over to the set of King Creole, and Sammy’d brought his kid sister Sandy along to watch. El had been marvelous. He’d come over to be introduced and then, worn out as he was from shooting a hard scene, he’d gone into his act for ten minutes just to give Sandy a thrill. And did she swoon! Man, Sammy’d been wondering how to tell Elvis that Sandy didn’t really dig him so much—she went for Pat Boone. But when El was done, he didn’t have to. Sandy was standing there with her mouth open and her feet glued to the floor. The next day she went out and bought half a dozen Presley records.

Yeah, Elvis had been great. And him a southern boy, too.

Slowly, Sammy got up from his chair and wandered about. This house—this wonderful house in a canyon, jutting its three stories out over the view—no one had tried to talk him out of buying this house. No one had told him a colored man couldn’t live in a house Judy Garland and Sid Luft had once owned. Everyone had helped him find it and furnish it, and they were all thrilled to pieces when his father decided to build right next door.

Anyway, they said they were glad. . . .

Debbie Reynolds had said it with even more fervor than the rest. “Maybe your dad,” she had added, “will be a sobering influence on you, Sammy. Make you put an end to those weekly poker games. . . .”

Sammy had shaken his head, laughing. “Why blame me? I didn’t start this jazz.”

“No,” Debbie had admitted, “but the games are at your place after all. Eddie doesn’t get home from them till three, four in the morning. I’m glad he has fun and all that—but when does a girl get to see her guy?”

Those poker games

She had had a point, Sammy had to concede. Tony Curtis’ wife had objected, too. And Dean Martin’s. He and Frankie were the only ones who didn’t have to fight anybody over it. But in the end it was Sammy who called a halt, not because of the ladies, but because what had started out as a dollar game had suddenly sky-rocketed into big money. Sammy himself had dropped $2,500 one night and won $4,000 another. If anything, it made him feel worse to take that kind of dough from a pal than to drop a wad of his own. So the poker games were no more.

But had it really been because they just didn’t want to play with him at his place? Had all his friends suddenly remembered that he was a Negro? And that they didn’t like Negroes?

It was too late to go to bed now. In another hour or so he’d have to start getting ready for his appointment.

Four hours later, a trim secretary opened a door, and Sammy walked into Mr. Goldwyn’s office. What he expected, he didn’t know.

And then, from behind a huge desk, a man was advancing to greet him. A hand was thrust into his and a voice was saying:

“So this is Sammy Davis, Jr. The richest man in all of Hollywood. . . .”

For a moment he thought he hadn’t heard right. He cleared his throat. “Oh— no, no, I’m afraid not,” he mumbled. “Most everything I make goes right off to Uncle Sam for taxes. . . Why, I’m just buying my first home. . . .”

But Sam Goldwyn only shook his head and laughed. “No, Mr. Davis. I didn’t mean money.” He walked away, turned back. “Mr. Davis, a man like you doesn’t need money. You have something more important. You have friends.”

He sat down behind his desk. “I’ve been in this business a long time. But I have never known anyone to have as many friends as you—real friends, people who cared. From the minute I announced that I was producing Porgy and Bess, my phone hasn’t stopped ringing. If I haven’t had fifty calls telling me that you are the greatest talent in the country, the perfect person for Sportin’ Life—then I haven’t had one.”

The richest man

Sam Goldwyn shook his head. “I never heard anything like it. Frank Sinatra. Jack Benny. Mary Benny cornering me at parties. Jeff Chandler. People I hardly knew, even. Incredible.” He sighed. He grinned. “If all Hollywood is calling to tell me you should have the part—who am I to say no?”

And across the desk, into Sammy’s hand, he pressed the contract.

Half an hour later, Sammy Davis, Jr. walked out into the sunny Los Angeles day. It was, he told people later, the happiest moment of his life. They nodded and clapped him on the back and told him how glad they were.

But they didn’t know the half of it.

For again, Sammy’s head rode high. He had more than the contract, more than the coveted role.

He had his friends back in his heart.

And it suddenly seemed so plain—and so foolish, his night of anguish. So his ‘friend’ the comic had made a crack. All right—the comic was famous for his occasional lapses from good taste. Everyone knew it—why had he, Sammy, forgotten it? It didn’t mean anything—not a thing. It didn’t even mean anything about his friend’s heart, his true feelings—except maybe that he considered Sammy a good enough friend to take it, understand it—and forgive.

And he could. Indeed, he could. Out of the riches of his life, out of the wealth of love and friendship on which he could draw, out of the warmth given and returned honestly all these years between him and his friends—from that deep source, he could take understanding and compassion.

Yes, it was so plain. For years he had told Negro friends, “I have found no discrimination in Hollywood.” And they, out of their many rebuffs and disappointments, had answered: “Wait and see.”

Well, he had waited. He had seen. He had seen that his friends had come through for him even when he didn’t know he needed them. He had seen that a fearful night like last night was never to come again.

He had seen, indeed, that he was the richest man in Hollywood. Maybe in the world.

THE END

Sammy will be in United Artists’ ANNA LUCASTA.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958