Nice Going, Mrs. James!—Betty Grable

The sharp buzz of the telephone, like a giant bee, slashed through the stillness of the polished mahogany-paneled library. The pair of glamorous legs which has become an international institution swung gracefully over the side of the fiery red chair. Clak-clak-clak sang the high heels on a pair of trim red 4B’s.

Plopping herself down on the ottoman, Betty picked up the receiver and said “Hello” in her little girl’s voice.

“Is this the Grable residence?”

Slam-bang went the receiver.

In a few moments the performance was repeated—all except the slam-bang.

“Do you, by any chance, mean the James’ residence?” asked Betty, with more than a hint of asperity in her voice.

This is the kind of thing that helps explain why Mr. and Mrs. Harry James’ relatives and friends searched Hollywood’s gift shops for a tin memento to commemorate the James’ tenth anniversary on July 5, 1953.

For in this elegant English-style country house there is no Betty Grable—merely Betty James. “I know it has to be Betty Grable on the marquees, but otherwise it’s Mrs. Harry James,” is how Betty puts it. “I’m old-fashioned enough to believe that a married woman shouldn’t keep her single name in private life. I just squirm when anyone introduces me as Miss Grable in Harry’s presence. And it makes him uncomfortable, too.”

The world’s most popular blonde and the world’s Number One swing trumpeter have chalked up ten years of happy marriage, despite the fact that any marriage counselor, back on that stifling, desert-hot wedding night in Las Vegas ten years ago, would have counted their chances slim. Hollywood’s wisenheimers, even without scientific training, predicted a quick bust-up. For these.two popular public idols seemed made to break every marriage rule in the book.

A good marriage, say the pundits, is most likely when both husband and wife have lived normal lives in solid, steady homes with two parents present. Harry James, son of roving circus performers, was born in that metaphorical trunk. His father was a circus band leader, his mother, an aerialist who swung from a trapeze until one month before her son was born, then rejoined the act when he was thirteen days old. At five he was a circus performer and at fourteen he had left home to travel with bands.

Betty, a saxophone tooter and a tap dancer in kiddie reviews in St. Louis before she was old enough to enter grade school, became a chorus girl in Hollywood at the ripe age of twelve.

Neither knew the established security of normal childhood home life. Betty’s parents, Conn and Lillian Grable, were separated for eight years and finally divorced. The daughter of an ambitious mama, docile Betty missed out on the proms, school chums, picnics and parties. Harry, a renowned trumpeter with his own band, was the darling of hordes of bobby-soxers. He worked hard and in his spare time he played equally hard.

According to such experts as Dr. Paul Popenoe, marriage counselor, Harry and Betty’s early years could hardly have molded them into solid marriage material.

The lanky jive artist with the Texas drawl married Louise Tobin, a Benny Goodman vocalist, when he was nineteen, fathered two sons and was still married, though separated, when Betty met him.

Betty was just sixteen when she told her mother she wanted to marry a saxophone player in Ted Fio Rito’s band. Mrs. Grable shrewdly surmised that opposition was futile. “Open your mouth,” she wrote her husband, “and they’ll elope tomorrow.” Instead she asked Betty not to marry until she was twenty-one. Betty promised.

And kept the promise almost to the day, though by then she had switched bridegrooms. A month before her twenty-first birthday she married Jackie Coogan, who as “The Kid” had earned some four million dollars. Betty was in heaven, thrilled over the huge engagement ring and the church wedding for which she became a Catholic.

A day before the wedding Jackie’s mother phoned, “If you think you’re marrying a millionaire you’re mistaken; he hasn’t a dime.” This grim warning bothered Betty not one whit; she’d worked since she was twelve and she went right on. Betty stood with Coogan through the sordid lawsuit with his mother which proved that his money was gone. But the marriage of the playboy and the pinup queen came apart at the seams.

A divorcee at twenty-two, the platinum blonde with the candy-box complexion really began playing the glamour circuit. Following her terrific success on Broadway in “DuBarry Was a Lady,” stage door Johnnies cluttered her path. She adored the American Beauty roses, the champagne, the plushy night clubs.

Back in Hollywood, her romances—with Victor Mature, Artie Shaw, Ty Power, Desi Arnaz, Lee Bowman, socialite Alexis Thompson, Jack Oakie, her agent Vic Orsatti, Bob Stack, John Payne—were photographed and written about in detail.

It was all fun. But when she met the much older George Raft she really fell in love. That romance lasted for some two and a half years, finally came to an end when Raft’s wife refused to divorce him. “I saw there was no future for us,” Betty summed it up at the time. “And I won’t get over him today, or tomorrow or next week.”

But she did. The year was 1943 and she spent much of her time getting over Raft by entertaining at the Hollywood Canteen. Harry James played often for the boys and Betty soon found herself attracted to the tall, lean, quiet guy with cornflower blue eyes, bluer even than her own. It was no “sudden youthful infatuation. Betty was twenty-six and Harry twenty-seven, and both knew instinctively that this was “it.” Harry left for New York. She visited him there soon after, parrying reporters’ questions on her break-up with George Raft. Nor did she tell them that Harry had asked her to marry him.

Four days before their scheduled wedding Harry was in New York and Betty in Hollywood, both sweating out the hours to learn whether his first wife had really obtained her Mexican divorce.

It was a hectic wedding in a neon-lit garish setting, far from family and friends. The kind of wedding that marriage counselors frown on. And the kind which too often has led straight to the divorce courts. Betty, with a girl friend and publicity agent, went to Las Vegas to meet Harry, who came by train from New York. At 5:00 am., they drove to the chapel of the Last Frontier Hotel. Sick at heart, they kept right on driving past when they saw an expectant mob in front of the chapel and heard a man yell, “Step this way, folks. They’ll be here any minute.”

“It was like a circus,” Betty remembers, unhappily, “and we called the minister and asked him to marry us in a hotel room. Then we bundled our huge wedding cake into the car and drove back to Hollywood—our honeymon merely a dawn-lit ride over the desert.”

Gossip columnists, in theatre parlance, predicted a short run for the marriage. They hastened to point out that the nation’s Number One Pinup girl had to remain in Hollywood while her bridegroom was on the road, playing in the nation’s dance palaces. How can you keep a marriage going that way, they asked.

Betty and Harry James ignored all these signs and portents. They knew they had a secret ace up their sleeves—the abiding love they felt for each other. Later they added the strongest link in a good marriage—children. From the beginning they adjusted their work schedules, made the most of precious shared hours—and all through the years continued merrily to peel July 5’s from their calendar. They will admit one problem, however. Anniversary gifts puzzle them.

“There probably isn’t another wife in town who would rather have a horse for an anniversary present than a mink coat,” smiles the all-time pinup queen. “But I’m that character. The most wonderful present Harry ever gave me was what you might call a three-in-one affair: a sweet-faced mare in foal with a colt trotting by her side! And the strangest present was one Harry gave me last Valentine’s day. He constantly ribs me about how nervous and excited I get when one of our entries is running at the track. There’s no point in my carrying a handkerchief because I shred it to pieces. Even the studio knows I won’t be able to sing the next day, because I report with a foghorn baritone. Well, when Harry heard that trainers give nervous horses shots of Vitamin B-12, he bought me a bottle and tied red ribbons and a heart on it. Hasn’t helped at all. I still blow my top at the track.”

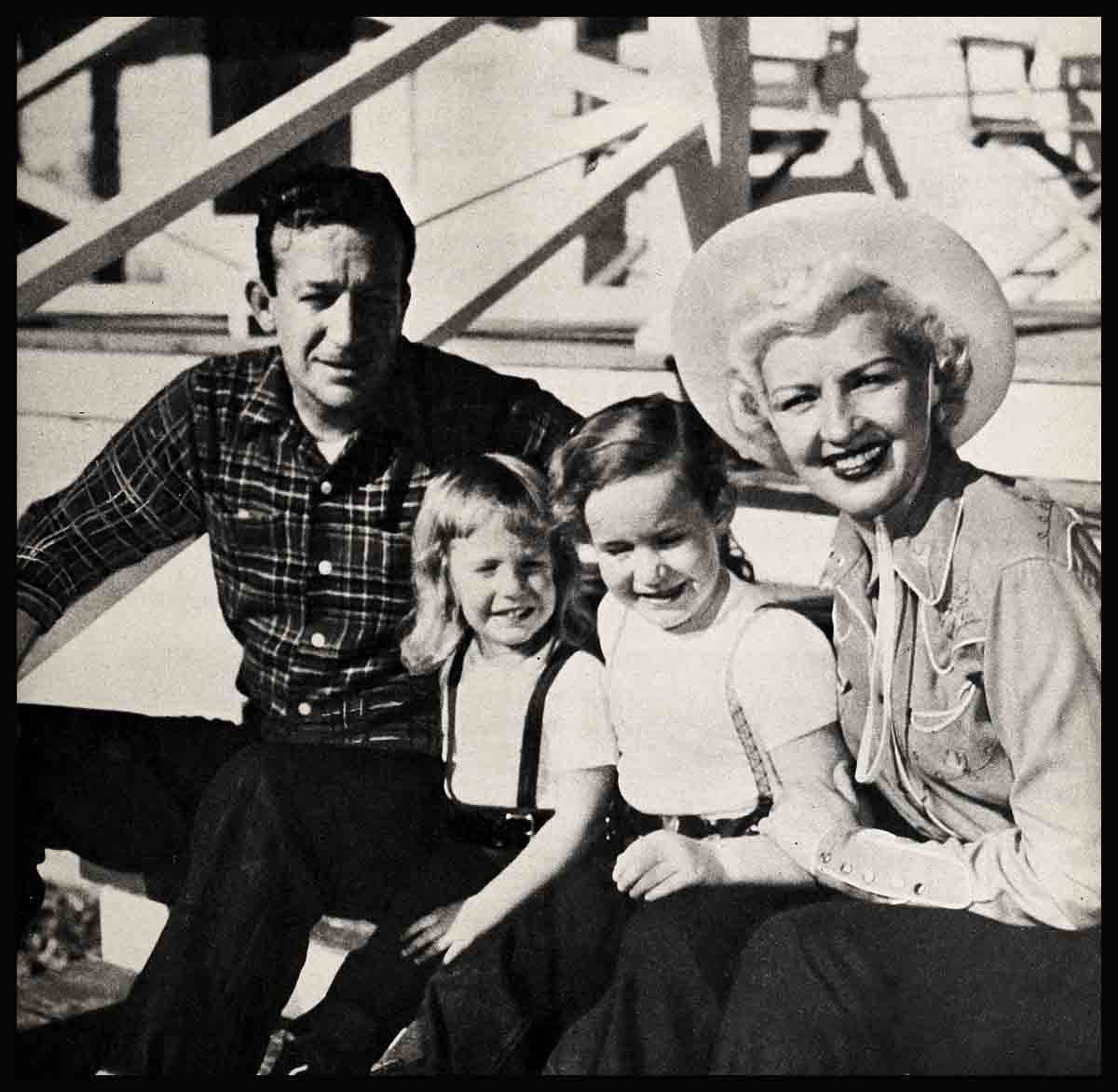

It’s the only place she does, however, for at home Betty is a calm, contented wife and mother. And it’s around two lovely auburn-haired girls—Vicki, nine, and Jessica, five—that the James’ family life revolves. From the beginning of her marriage Betty decided that the only way to keep her two careers on an even keel was by rigidly restricting each to its proper place.

“When we were decorating our house,” recalls Betty, “minor crises turned up one after the other. The maid called—but she only did that once—and asked me to rush right home to settle the problem. Imagine! What did she think I have here at the studio but problems?”

The studio problems Betty handles easily. Two dozen years of dancing and singing in some forty motion pictures have made her a perfectionist. At the same time, they’ve given her no false sense of her real potential as an actress. When she heard that Preston Sturges had declared she could be a great comedienne if she’d forget her legs, she said simply, “Nuts. It’s my legs that made me.” Asked to explain what Grable has that has earned her studio more than fifty million dollars and given her one of the largest salaries paid any star at any studio, she flips, “I’m just a gal that truck drivers like.” And though she has been three times listed by the Treasury Department as the highest-paid woman in the whole country, she once told a reporter, “Excuse me, please, while I go act. If you can call it that.”

At the studio she devotes every bit of her fantastic energy to making the best pictures she knows how. But her firm “no” can be heard across the set when she’s asked to hold still for publicity which will cut into her free time with her family—although she has a healthy respect for the fans who have brought her stardom. But she’s been all through the rough-and-tumble days when gag publicity was vital. And she just isn’t having any more.

Naturally this makes her off-stage life, from a news standpoint, as unexciting as if she were living in Nellie’s Apron, Arkansas. And that’s how she wants it—though the night spot photographers may weep. The moment Betty enters her beige Cadillac at 6:30 p.m., she turns off her studio glamour, like a faucet.

“I don’t know how some actresses can work day after day and have themselves a ball night after night when they have children to bring up,” says Betty. “I don’t know how they can go traipsing all over the globe and leave their children to be brought up by maids. I’ve never been to Europe or Mexico or Hawaii . . . not even to Sun Valley. Harry and I feel that traveling and sight-seeing can wait until the girls are older and we can all go together. Meanwhile I may be a spectator at the races—but never a spectator mother.”

This is easy to verify. It’s Betty in bathing suit who climbs into the shower to personally suds the soft baby curls of her daughters; who shops for all their clothes; drives them to parties, to dancing classes, to the pediatrician fer eheckups. It’s Betty who never misses dinner with Vicki and Jessica and tells them their favorite fairy tales. (“And woe is me if I leave out so much as a comma.”)

And had you been on the set of “How to Marry a Millionaire’—Betty’s latest picture—you’d have seen still another side of Betty, wife and mother. She had just finished a scene in which her gorgeously filled blue dress had elicited wolf whistles from the crew. And then she trotted over to a wall telephone. Standing on tip toe to reach the mouthpiece she read from a long list, “Two pounds of butter, three pounds of green peas—and are you sure they’re nice and fresh? . . . I’d like some lamb chops, but the cook said the last ones you sent weren’t spring lamb. . . .”

Even if she’s making a picture in December (which means six full days of work a week), you’ll still see her trotting around to the shops that stay open late, buying Christmas gifts for the children and her relatives.

A certain director’s wife has definite knowledge of this. The maid came back from her day off to announce breathlessly: “Guess who I saw at Sears-Roebuck in Westwood buying kitchen curtains? Betty Grable!”

A few years ago Betty and Harry moved into their third house, although it is the first they’ve furnished—a twelve-room English-style brick house, shaded by huge eucalyptus trees and boasting two acres of lawns. The house, in the old Doheny estate, is a quarter of a century old. “At first sight,” explained Betty, “I thought it looked like a Boris Karloff set, dark and gloomy with five of the seven fireplaces boarded up. But it was beautifully built, the rooms large, and the price right.”

They proceeded to chase the gloom with lots of red (Betty’s favorite color), forest green and sunny yellow to set off the beautifully paneled walls, and to install all their horse trophies. The little girls share a huge bedroom papered in blue and white plaid, filled with white furniture and two gaily canopied blue and white beds.

Betty will tell you that “Harry doesn’t toot his horn at home—the only trumpet has been made into a lamp—nor do I practice my dances or study my scripts. We shut out that part of our lives when we close our front door. The other evening Harry brought home a record made by one of our friends. All through dinner he told me how really super it was, filled with unusual musical effects. I could hardly wait to hear it. We rushed into the den and put it on the record player there. It wouldn’t work. Then we ran around trying the three or four others we have around. None of them played. Finally we tramped up to the children’s room and played it on their Mickey Mouse record player! It sounded horrible—tinny and out of tune. Both of us burst out laughing. ‘Fine show-business people,’ said Harry. ‘The cobbler with the unsoled shoes.’ ”

The James television set, though, is kept in good repair. For Betty, alone a good part of the time at night, sits herself down, after she’s kissed the girls goodnight, to watch every gory murder mystery she can find. If her mother is visiting she’ll say, “Mother, please keep your bedroom door open tonight. I’m afraid that ghosts may forget the program’s over.”

Though their house has a huge living room which would comfortably hold fifty party guests and a dining room with three mahogany tables which fit together to make a huge buffet table, they practically never entertain. So Betty is beginning to think they might like a smaller house, contemporary, but not too coldly modern. “A large room with dining, den and living areas all together,” she day-dreams, “where we could put the television set, shuffleboard, Harry’s pool table, the children’s doll house and their spinet. It might give an interior decorator the whim-whams, but I don’t care.”

Betty’s eyes grow dreamy as, in her mind’s eye, she sees that house taking shape. Then her eyes grow puzzled. “I can just see myself moving into that dream house. I wish some smart guy would explain to me, why, when moving time rolls around, Harry always manages to be on the road with the band. I’ve heard the same thing from other wives. Maybe we ought to write to Dorothy. Dix’s advice column. I’ve moved three times—and always by myself. Maybe I ought to ask that husband of mine if he’s psychic.”

If Harry isn’t, it’s probably because he knows how efficient Betty is. If there is anything she can do for herself, she does it, for she hates to be waited on. She’s always a perfectionist—hates disorder or messiness; is forever emptying ash trays, straightening pictures and doesn’t wait for spring cleaning to tidy closets.

All the same, she’s not really domestic and maintains that cooking is something she just “can’t get with.” If the cook is out she will gather her brood and dine out—that way she knows they’ll get all their vitamins. Still she loves to eat and has a wrestler’s appetite. Her favorites are simple foods—hamburgers and hot dogs—followed by a rich, gooey dessert. Yet her measurements have scarcely changed in years and her legs are still unchallenged as the world’s finest. She doesn’t need to diet: the hours of dancing burn off any fat accumulated by her three hearty meals and two between-meal snacks.

You’ll never find Betty running up a fine seam or putting up a supply of jam for the winter. She was never exposed to feminine interests during her hoofing, chorus-girl adolescence.

So it is that this earthy gal (whose humor is sometimes unprintable) likes men better than women and has only one close woman friend, Betty Ritz, wife of Harry Ritz. Her interests, aside from those of wife and mother, are mainly Harry’s interests: horses and horse racing, bowling, baseball, football, the fights, poker and gin rummy. At cards, she’s a hard loser. “Hmm,” she says to Harry. “You had all the good ones.” Even when she wins she tells him, “You let me win.”

But when one of the James horses wins a race she knows it’s real. Big Noise, born and bred on their ranch has won more than $100,000. Betty still sees him as a wobbly-legged little colt, hardly able to stumble around. Just talking about him raises a lump in her throat.

But she laughs when she remembers a racing incident that happened when Vicki was three. The little girl overheard Betty making arrangements on the phone to attend the races one afternoon.

“Please, Mommy, take me,” begged Vicki.

“No, dear, races are not for little girls. When you’re older I’ll take you.”

Upon Betty’s return, Vicki met her at the door, a big scowl darkening her usually happy face. “Mommy, I listened to the radio and heard the man say, ‘This race is for three-year-olds!’ ”

With its interest focused on home life, the James marriage has been, from a news standpoint, truly a dull one. Yet the rumor mongers have been busy. And whenever Betty has gone to Ciro’s or the Mocambo to catch her favorites—Joe E. Lewis or Billy Daniels or Kay Thompson—the columns have hinted that the Grable-James marriage was on shaky legs. Betty hated to give these rumors the importance of denial. Yet, heartsick over their effect on Harry on tour in distant towns, she has from time to time begged her studio to set things right. “I was out with my best friends, Betty and Harry Ritz,” she explains or “I wasn’t even at the Club Deauville the other night.”

During the past ten years Hollywood has had to admit their fears for the James marriage have been groundless. And the principals figure it this way: their marriage can’t last any longer—no longer, that is, than a lifetime!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1953