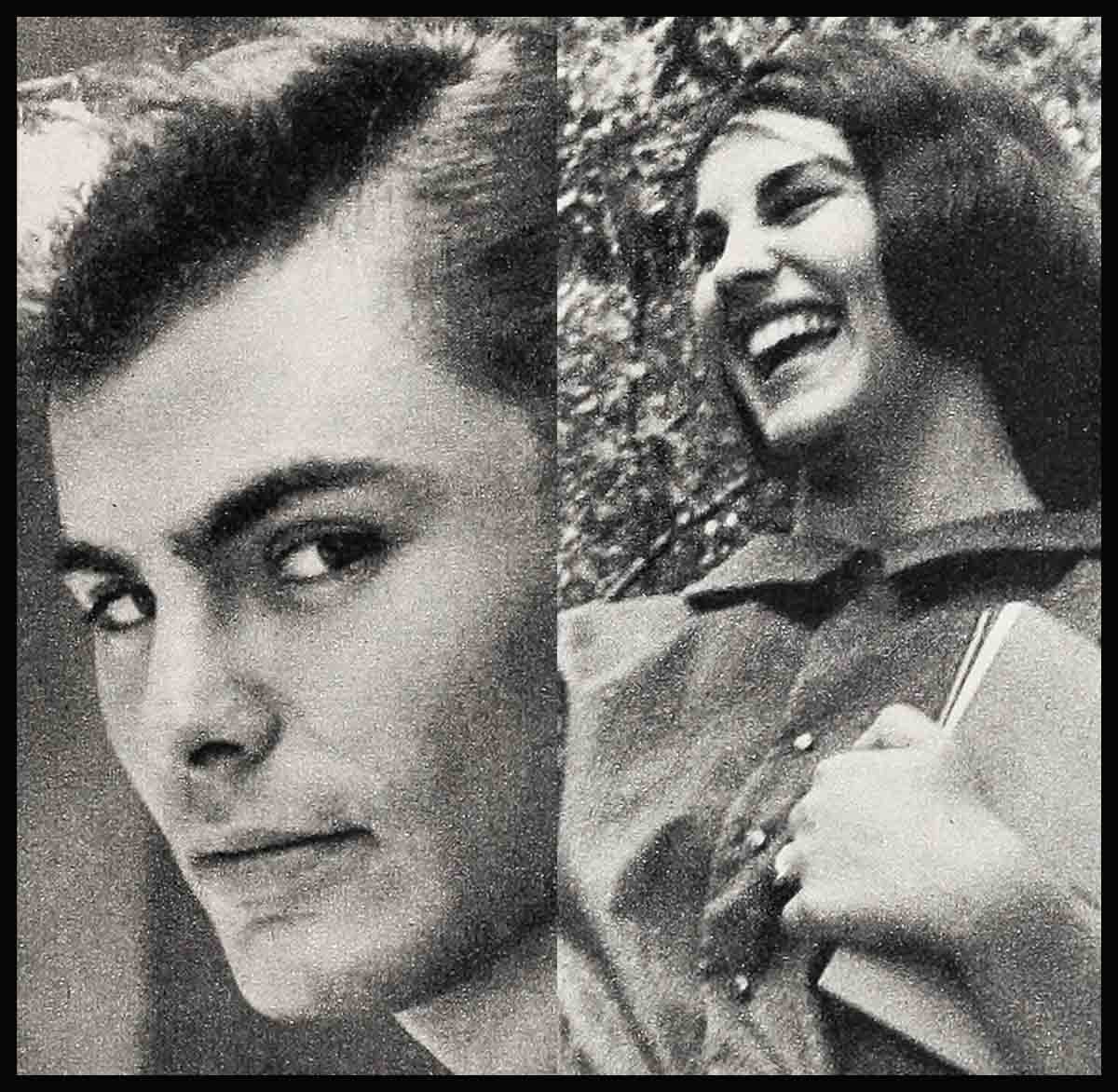

My Brother Johnny Saxon

What do you do with them? Big brother, that is. Put them in their place!

That’s what I learned after too many years of taking my brother Johnny’s guff.

The first time I rebelled was at dinner one summer. Johnny wasn’t a movie star then, and I was much heavier. He went around calling me chubbyface and fat-tub-of-lard, an I’d sit and suffer a slow burn. He was right, of course. Big brothers usually are. I was chubby, and I should have watched my weight. But his big trouble was the way he told it to me. He never had any regard for my feelings. Always, whenever there was company in our house, Johnny’d manage to say, “Hey fatty, when do you intend to reduce?” and I’d run into another room, embarrassed.

This fat-stuff jibing of his had been going on for some time, and I finally convinced myself I’d had it right up to my neck.

This one night we were all eating dinner at our house in Brooklyn—my mom and dad, my brother Johnny, and my younger sister Julie-Ann. We were having veal scallopini, an Italian dish my mother’s an expert at fixing. I asked for a second helping, and Johnny made a crack about what a glutton I was.

I held back for a minute, didn’t say anything. Then when Johnny started yelping at my mother for his dessert because he had a date and was in a hurry, I said, “Who’s your date with? Pieface?”

Johnny was dating a pretty Greek girl, Genevieve, down the street, and she was no more a pie-face than Liz Taylor. But I just had to strike back. Fair was fair, I figured. This was the first time I ever said anything upsetting to him, and boy, did he let out a howl!

He got up and reached for a pillow on an armchair behind him and he threw it across the room at me. He missed, but my mom and dad chewed him out for being such a troublemaker.

Soon as dinner was over he ran upstairs to get ready for his date. I waited for him on the front porch. When he came down, all spiffed up in a striped tee shirt and white pants, I said to him, “Don’t forget to tell Pieface I said hello.” He chased me all around the block, caught up with me, shook me and made me promise I’d never call me Genevieve a pieface again. I told him I’d agree only if he promised never to call me fatso. We shook hands on the deal, but I had the last laugh. He sweated so much from the chase he had to go home and change his clothes!

That was the beginning, my first how-to-deal-with-a-big-brother lesson. He never mentioned my weight again. Anyhow I finally got wise to myself and reduced.

Another thing I learned about big brothers—they don’t like to hear the truth. I’m not saying you have to lie, but I am saying you’ve got to be diplomatic with them. Unless they beg you for your opinion about something that’s personal to them, keep it to yourself. You’re better off because you’ll probably avoid a battle.

One day one spring Johnny came home with some pants he’d just bought to wear to a spring dance at school. The theme for the dance was “Be Happy—It’s May!” and Johnny decided to dress up in spring colors—a pink shirt, green necktie, white jacket and maroon trousers.

After I saw the pants, he asked me what I thought of them.

“That color!” I said. “It’s weird. What’s so springlike about maroon?”

He said the potted plant my dad gave to my mother that Easter was red. Dad gave mom an azalea. Johnny could never remember the name of it.

“I don’t dig them,” I told him about the trousers. “Anyhow,” I said, “the azalea isn’t maroon. It’s an off-red.”

“So what do you want me to do—dye the pants to match?” he growled at me. “This is the closest color I could get.”

“Put them on,” I told him.

He went into his room and changed into them. When he came out, my mom, sister and I roared as soon as we saw him.

The pants were wild—broad in the backside and pegged at the ankles. They had pistol pockets and white piping down the sides.

“What’s so funny?” he wanted to know.

My mother and sister couldn’t stop laughing. I had to open my mouth and say, “You look like a hood.”

That’s all he had to hear. He lunged at me, and another wild Orrico chase was on. We both slipped on my mother’s waxed hardwood floors, and I hurt my crazybone. Johnny came through unscathed.

Second lesson

He wore the pants to the spring dance that Friday night, and on Saturday I asked him what the rest of the kids thought of them. He said, “Great. Everybody thinks they’re the greatest.” I went to Lou Hessing’s luncheonette around the corner from where we live to have a Coke that afternoon, and all the kids from the high school were sitting in the booths talking about last night’s dance. I sipped my Coke at the counter and eavesdropped. Everybody was making fun over Johnny’s crazy maroon pants. And from the way they talked I could tell they had told him what they thought of them. One of the girls in the booths said, “Putrid. That’s what I told him they were. Putrid! And I thought he was going to cry he was so hurt!”

So I learned my second lesson in handling big brothers. Don’t tell them the truth when it comes to their personal taste. They’ll hear about it soon enough, and comments from outsiders will make a bigger dent than yours will.

Johnny, in case you’re interested, never wore those maroon pants again. My mother used to ask him what he did with those funny pants, and he changed the conversation every time.

This leads me to lesson number three. Big brothers don’t have a sense of humor. They don’t understand a tease; they take it seriously. So look out if teasing comes naturally to you. Dollars to doughnuts it’ll make your big brother boil.

I was in my early teens when this happened. I was sitting on the steps of our front porch daydreaming one summer day, and a couple of older girls were walking by. I decided to have some fun.

“Hey dreamboat!” I called out.

Both girls turned toward me and smiled.

“No,” I said. “Not you, shipwreck!”

The girls’ faces reddened. One of the girls came toward the porch, but I jumped off the side and ran to Big Brother Johnny who was weightlifting in the backyard. Both girls followed me. It turned out one of them dated Johnny. Do you think Johnny offered me protection?

Not on your life. After they told him what I called them, he made a face and said I deserved to be slapped, and he came over and slapped me lightly on the cheek. I was shocked, and although the slap didn’t hurt me at all—I could tell he was putting on an act—I let out a scream and started to bawl like a baby. Johnny walked off with both girls. Huh, I thought, I’ve fixed him up with a couple of dates.

When he came back home he gave me a lecture about keeping my mouth shut.

“I only did it for fun,” I told him.

But he refused to listen to me. He was the Big Brother, and I was Younger Sister, and he was bound and determined to set me straight.

Later on I reminded him about the episode. I was laughing myself sick remembering it. After I told him about it, I thought he’d laugh, too. “Oh,” he said, lifting his eyes from some serious book he was reading, “I remember. That’s when you were a child.”

He never even cracked a smile.

Telephone troubles

If you have a big brother, you’ll know what I mean when I say ‘telephone calls,’ and ‘girls.’ You’ve got to put up with both every day. The telephone’s always ringing, and it’s usually some female with a mooning voice asking for the Big Boy.

One time I told one of them—she was just too dreamy for words—Johnny was so heartbroken over a rotten love affair that he ran and enlisted in the Merchant Marines, and she started to sob over the telephone. “He didn’t even call to say good-bye,” she sniffed.

“I know,” I said, “isn’t it a shame? He didn’t tell any of us, either.”

When she found out the truth, she wanted my scalp—natch. Fortunately Johnny wasn’t especially interested in her, so we didn’t have the usual knock-down, drag-out clash.

But big brothers are generous. Generous with a capital G. Ask any sister with an older brother, and she’ll testify to that. If some stranger wanted advice on weightlifting or baseball or BB gun shooting, all he’d have to do is ask my brother for some tips. Before you knew it, Johnny’d be lending him a bat or a baseball or the use of his gun. But let me, Dolores, ask

Johnny for the loan of an old shirt I want to wear to a wiener roast, and his big-brother big-heartedness comes through.

“If I catch you taking any of my shirts, so help me I’ll report a theft,” he’d say.

Big brothers—they’re so sensitive. If you’re waiting for a call from some special somebody who’s promised to ask you,out on a Coke date, then Big Brother’ll get on the telephone and talk with one of his piefaces for hours. But let me be on the phone for a minute, telling a girlfriend I’ll meet her at Lou’s luncheonette, and if he’s expecting a call from one of his hundred females, he lets out a war whoop like a Sioux Indian and doesn’t let up until the telephone’s free.

Truth is, there’s another side to the Big Brother personality. After a few years go by and he sees that his sister has developed into a human being and buried her monster manners with the past, he might take notice and might be likely to do some pretty nice things. Johnny has.

My date with Johnny

Last winter when Johnny came home for a visit from Hollywood, he said, “Shucks, Dee, I know it’s not in Emily Post, but you know what? I’m going to take you out on a date.”

He said he’d call me from New York that afternoon, and he’d tell me where to meet him. He had to take care of some business details in the city, and there wasn’t any sense in his coming back to Brooklyn to pick me up.

When he called to tell me to meet him at 4:30 in the Palm Court of the famous Plaza Hotel for some English tea, I asked him what did he want me to wear.

“For crying out loud, I don’t know. Dress up. Dress for the theater!” He sounded so blasé.

I put on a new dress—a navy blue chemise with navy blue stockings and mid-heel pumps.

When I got to the Plaza, he looked at my outfit and said, “Where did that miserable sack come from?”

I told him I bought it at one of New York’s best department stores.

“You look like a lopsided balloon,” he said and he sent me all the way back to Brooklyn—an hour’s ride on the subway—to get into a ‘decent’ dress.

I met him at seven o’clock at the Vesuvius Restaurant wearing a neat-fitting red sheath, and he thanked me for looking civilized.

We ordered clams casino and steak pizzaiola, a fancy Caesar salad and broccoli with Hollandaise sauce. I was thrilled. I’d never eaten in such a fabulous place before. By dessert time when we were having strawberry parfaits, everyone in the restaurant was looking at Johnny and his date—and I felt like a celebrity.

After we finished our parfaits, the waiter came over and asked Johnny for his autograph. Then the waiter asked me how it felt to be a sister of a famous movie star.

The whole illusion I was trying to create was ruined. How did the waiter know! “Who told you I was his sister?” I said to him.

He said, “Nobody. I can see it in your face.” So my lovely dream of posing as a deb date for Johnny was shattered.

That night we went to see Tony Perkins in the Broadway play, Look Homeward, Angel, and I was so moved at the end of the play when Tony leaves home and embraces his mother for a last good-bye that I soaked up three hankies with tears.

Afterwards we went backstage and talked to Tony. Joan Fontaine was leaving Tony’s dressing room. She, too, had seen the play that night, and she was scolding Tony for not calling her for lunch.

When Johnny introduced me to Tony, I almost sank to the floor. Tony has a way of saying a girl’s name so softly that it sends thousands of little chills up your spine. I nearly swooned.

Cinderella at Downey’s

We went to Downey’s Restaurant then where all the young stage and screen stars go, and we ordered espresso coffee. Lena Horne was there and I was thrilled.

Lena looked beautiful. She was wearing a white angora sweater with a pearl-beaded collar, and a pale pink wool skirt, and all I did was stare at her—which is rude. But I couldn’t help it. She has such striking, delicate features; and anyway I flip whenever I see a celebrity in person.

Johnny talked to some of his friends about acting and Hollywood and how he hopes to do a Broadway play some day, and then he looked at his watch and said, “For Pete’s sake, why didn’t you tell me? It’s after midnight. I’ve got to get you home. It’s way past your bedtime.”

Was I humiliated! Sure, I’m only seventeen—but there it was, that aggravating big-brother remark that made me feel like two cents.

I looked straight into his eyes and said, “I’m not going to turn into a pumpkin.”

Then he looked up and stared at me for a moment. Soon he was laughing that snickering little laugh of his. “I guess you won’t,” he said softly. “I guess you won’t after all. You’re a big girl now.”

In a little while we went home. He splurged and treated us to a taxi which cost five bucks. He told me now that I’d shown him what a lady I was he’d take me out at least once every time he visited New York.

We arrived home, and Johnny got out his psychology book—he’s a bug on psychology —and he said he was going to read a while. I thanked him for everything, and he told me it was a pleasure to spend an evening with a grown-up sister. I went up the stairs to my bedroom thinking of all the battles we’d had. I remembered the times I tried to teach him to jitterbug and how he’d yell at me when he tripped all over himself. I remembered all the times he chased me for being a conniving brat, and I wondered if there’d be other silly fights and arguments. Probably. He’d always be my Big Brother and there’d be times when we just wouldn’t agree on things.

I got ready for bed. I said my prayers and crawled under the covers. But I couldn’t sleep. I decided I had to tell him he was pretty wonderful. I put on my bathrobe and I went to the head of the stairs and I called in a loud whisper.

“What do you want now?” he said in an irritated tone of voice. I guess he was deep in concentration over his book.

Something inside me told me to hold back.

“I just wanted to say good night,” I told him. I don’t think he even heard me. Something told me to leave well enough alone. Sure, I was proud of Johnny. He knew it. I didn’t have to say it.

Because if I didn’t look out, that mysterious voice inside me warned, big brothers can be spoiled too!

THE END

—by Johnny Saxon’s sister, Dolores Orrico, as told to George Christy

Johnny is in THE RESTLESS YEARS for UI.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958