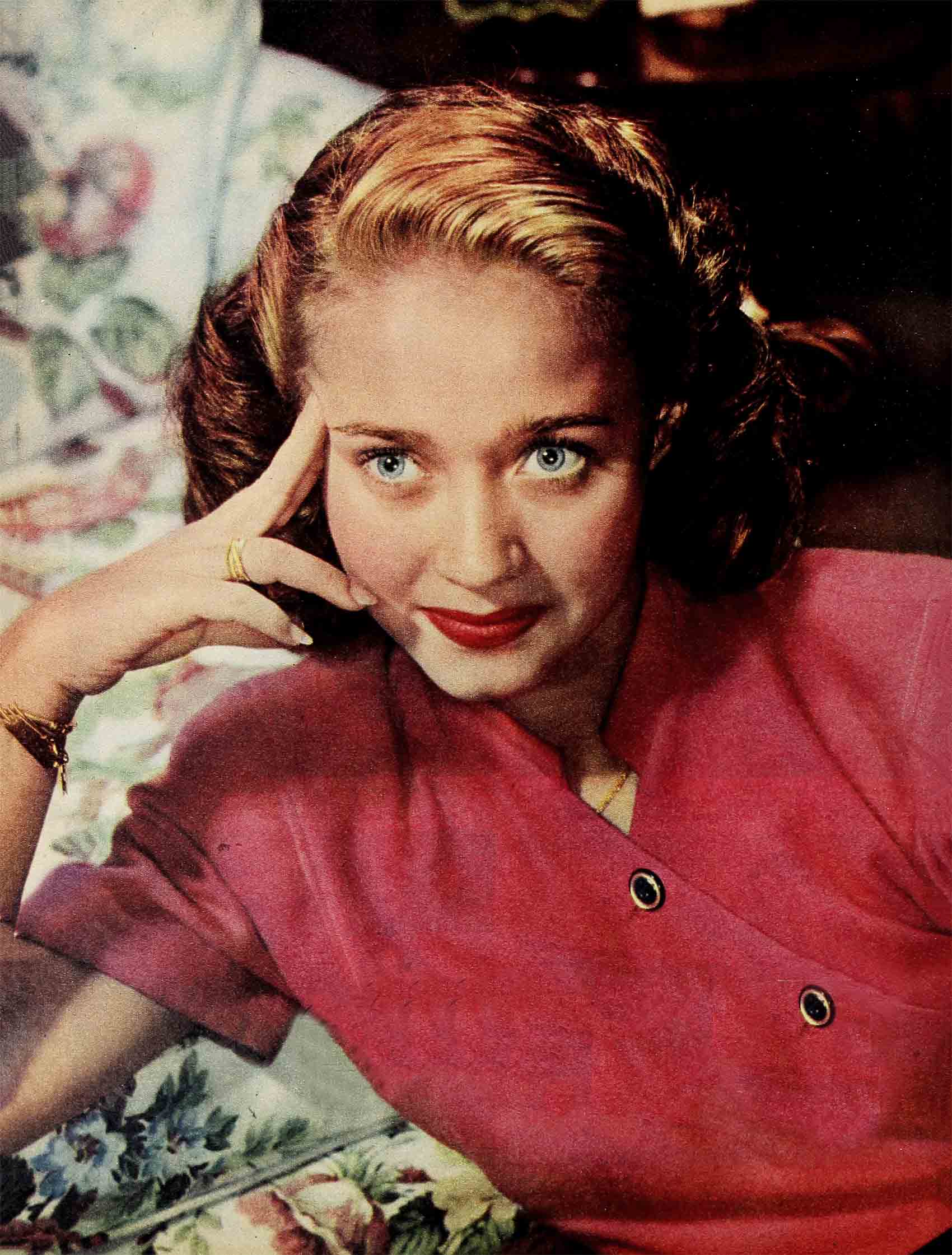

First Love—Jane Powell

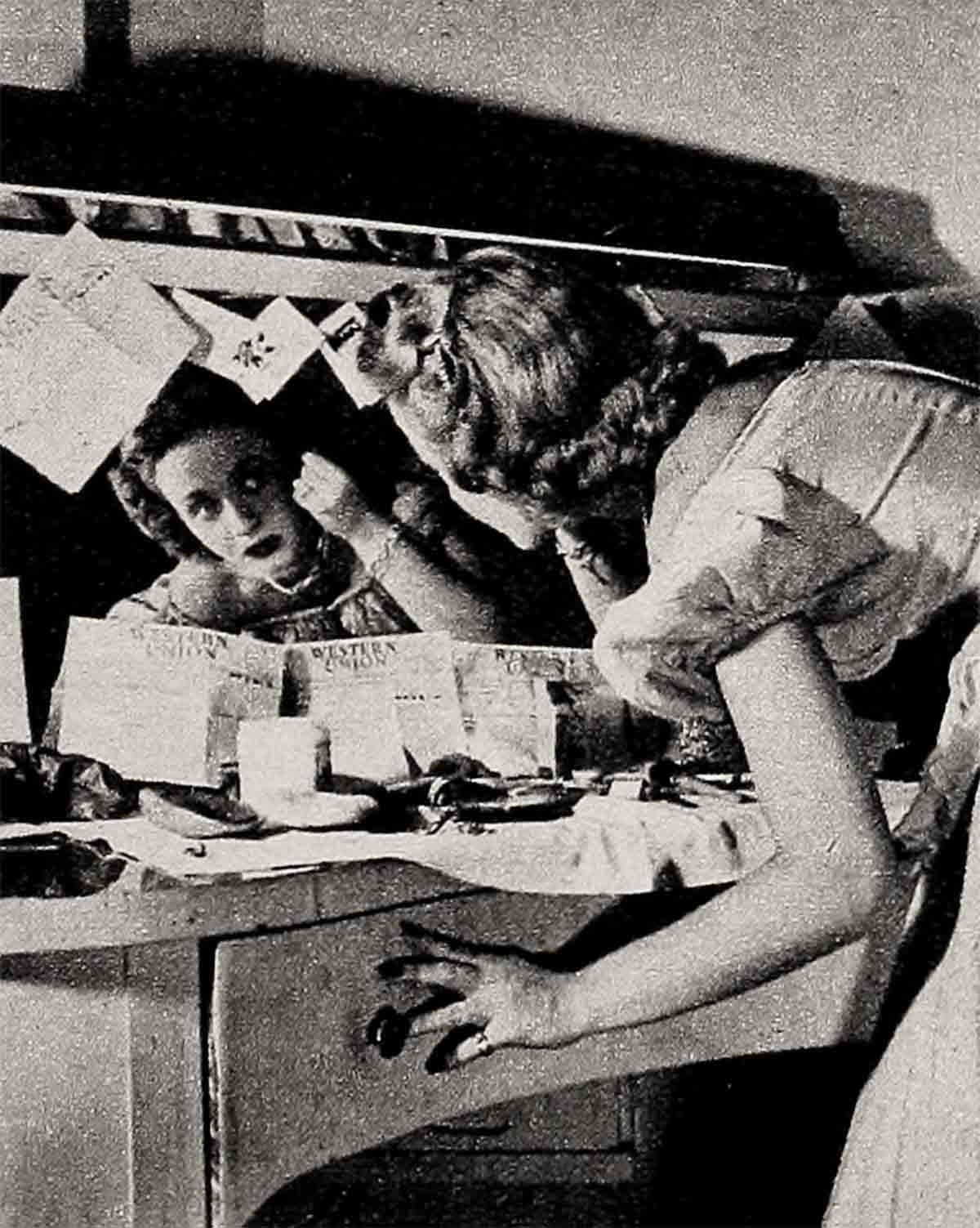

Backstage at the Capitol Theater, she was getting into the Bergdorf dress (shocking pink, and sensational) when the flowers came.

“Orchids again,” Mrs. Burce said.

Jane sighed. “Every day. He’s so nice—for an older man.”

Her mother looked surprised. “How old?”

“He must be thirty,” Jane said, ending the discussion.

Shortly thereafter, she went out, did three songs, and one encore, came off, wiggled out of the Bergdorf dress, creamed her face, and sagged.

“The makeup is wrecking my skin,” she said. “And I’m tired.”

“And there wasn’t any letter from Tommy today,” her mother noted. “Is that it?”

She had to grin. Not that she didn’t have a right to be tired. The train trip, and the confusion, with Jane coming in to one of New York’s two railroad stations, while her agents (MCA) were dutifully meeting her at the other. The two weeks of five shows a day (a different dress for every show) and eating in a million restaurants, so that your stomach was a little off, and never getting to bed because there was so much to see.

She was tired, all right. But the fact, remained that Tommy hadn’t written; there hadn’t been any letter today, and maybe you could blame the mood on that, and not New York.

People in New York had been swell. There were crowds of fans at the Capitol’s stage-door every night, and once, when it was cold and rainy, and there wasn’t a cab in sight, one of the kids had disappeared, and come back in five minutes, triumphantly riding a running board.

“A cab,” she said. “For you.” And Jane had never even found out the kid’s name.

New York had much to recommend it, and if there was something missing, you could only decide that the lack was in you.

There was another night (that day, a letter had come) and Jane and a girlfriend, sitting in the hotel, had an inspiration.

“I’ve always wanted to take a hansom around Central Park,” Jane said, and the other girl said she had, too, and they grabbed coats, and went out into the street, and hired themselves a cab.

It was a wonderful night, full of stars, and the air not too crisp for comfort, and they sat back, feeling luxurious, and Victorian.

“Romantic,” the girl friend said.

And then they both giggled. “But not with you!”

With Tommy, Jane was thinking. Ah, with Tommy . . .

It was strange to look back. There was a time when she’d been almost bored. For an eighteen-year-old girl—well, lacking only a week or two—who was healthy, beautiful and possessed of a fine fat contract with M-G-M, this was an unusual state of affairs. She had on a brand new evening dress this one night; her hairdo was impeccable; and she was sitting at a table in Earl Carroll’s very swank, very glamorous theater-restaurant, watching one of the biggest benefit shows of the season. All the photographers had been by, and stopped, and set off flashbulbs in her face. Three young men, handsome but somehow anonymous in their dinner jackets and tans, had asked her to dance. It was February, 1947.

And something was missing.

what’s wrong with this picture? . . .

It would not have been easy for anyone in that night club, even Janie’s escort, to have diagnosed what was essentially wrong. It was something to do with the night, the new moon, the music.

Janie, to simplify this, was just ready to fall in love, that’s all. She had never been in love before, and she would have hooted at the very idea, but there it was.

And there was Janie, just ready. And presently, wearing a dinner jacket like everybody else, his dark hair somewhat mussed from driving in an open car, his nice, young round face flushed from the cold air, and one of Janie’s best girl friends on his arm, there came to the table Thomas Batten, 21, Kappa Sig, Senior at the University of Southern California.

Three years before, he’d been at Metro on a contract, and he and Jane had studied together but they hadn’t seen each other since.

During her second dance with him, Tommy said, “My fraternity is tossing a dance at the beach Saturday night. Kind of a spring thing, to open the season. Want to come?”

“Yes,” said Janie.

“Three years ago,” he went on thoughtfully, “I never realized—”

“You never realized—?”

“I mean, could I give you a ring about next Saturday?”

So there it was. Tragedy. New house, in the valley. No phone. The company had said, “In a few weeks.”

“That’s the way it is about the phone,” Janie said, in further explanation. “But you could give me a call at the studio. I’m on a picture. How about that?”

“Mmmm,” he said, dubious. You called the studio, you went through thirteen secretaries, you got the stage, someone said, “Sorry, the red light’s on.” You waited. Next time the one set phone was busy. He knew that routine.

“I’ll try,” he said.

On Friday afternoon, she had all but forgotten the incident. (Not quite, of course: you do not entirely forget first important moments.)

As a matter of fact, she was in her dressing-room collecting the things she wanted to take home for the weekend, when an assistant director came up to the door and said, “Telephone, Janie.”

Tommy was very nice about the car, in his diffident, almost shy way. It was a Chrysler convertible of ancient vintage, which he’d had before the war and somehow managed to hang onto all through his service. When he brought her up to it, at the curb in front of her house, he said, “If you’ll wait just a minute—” and then proceeded to spend a minute and a half untying the knot in a sturdy section of clothes line. As the knot gave, finally, the door sprang loose and fell into the street.

breakaway jalopy . . .

“Oops!” he said. “I forgot to hang on to the back part.” He retrieved the door. She got in. He put the door back, and tied it.

“We’re off,” he told her, and for a minute or two they drove in anything but silence, although neither spoke a word.

Janie giggled. “You’ve gone five blocks and you’re still in second.”

After a moment’s pained pause he said, “We’re in high. It was second we started in. Low doesn’t work.”

Eight blocks later he said, “You should have brought a scarf for your hair. It’s kind of blowing.”

“We might put up the top, then.”

He didn’t answer that.

She said finally, “I’ll help.”

“I can put it up myself. Only there’s just half a top. The rest is ripped. You get a worse draft when it’s up.”

She began to laugh. “I’m happy. And I can comb my hair at the dance.”

She had never meant anything more sincerely in her life.

After the Hollywood boys she was used to, Tommy was like someone from another world. He said he’d finished all his premed training, and quite simply had decided that being a doctor was too hard a row for him to hoe. “Besides,” he explained, “it’s getting so everyone specializes, and that takes even longer. I’m twenty-one now. My gosh, I’d be an old man before I ever got anywhere.”

So he was getting his degree in entomology—which he’d probably never have occasion to use—and helping out his current income by assisting a professor of physiology.

“Sounds like a lot of studying,” Jane said. “Dorsal aortas, and all.”

He looked at her in surprise. They were sitting out a dance in the lounge, having a coke. “What do you know about dorsal aortas?”

“I took zoo. The dorsal aorta is just back of the post caval vein, and where would your renal arteries get off without it? Now ask me about malphygian corpuscles.”

“I’m convinced you have a brain,” he said, “so let’s dance. For aortas and corpuscles, I have Doctor Beers. For fun and dancing, I have you. Come on.”

That night, when he took her home, it seemed perfectly natural that, after raiding the icebox and eating cold lamb sandwiches, he should kiss her goodnight at the door.

The first time he came to dinner, he arrived by way of the garden and the back door. “I don’t usually do this when I visit people’s houses,” he said, “but there was a slight obstruction called a skunk sitting on your front porch. Maybe it will go away.”

“Indeed,” Jane said, “it will not.” She went to the front door and opened it, and the skunk, tail high, came mincing in.

“Oh, now look here,” Tommy said.

“This is Scent of Jasmine, called Jazzie for short,” said Jane. “Certain alterations have been made and she hasn’t any fight left in her. How about a swim before dinner?”

They went dancing at the Florentine Gardens that evening, and when they got the car from the parking lot Janie slid under the steering wheel, from his side. They drove out into the street, stopped at the red light, and the door fell off.

While impatient horns behind them grew more insistent, Tommy got out. “Oh Lord,” he said finally. “The rope’s busted.”

“Well, throw the door in the back and we’ll go on without it.”

“Too dangerous for you,” he shouted above the deafening horns. From the turtleback, he brought an enormous ten-foot chain, meant for towing purposes. He secured the door with that, and they drove on at last, clanking like Scrooge.

After that Tommy had no alternative but to wire the door permanently shut. When in formal evening dress, Janie walked around and slid under the wheel. When in slacks, she learned to climb cheerfully over her own side.

two lives have i . . .

The spring wore on, and became summer, and Janie had two lives. One was at the studio, working like mad, clowning with the enchanting Iturbi, practicing her music. The other was the gay college social whirl, always with Tommy. They danced. They sat around bonfires on the beach, and ate charred hot dogs. They drove for hours along the coast, watching the moon.

Once, at breakfast, Mrs. Powell said rather anxiously to her daughter, “But you don’t see so many of your old friends any more. Just these college people. Don’t you miss the kids who are in pictures?”

“I like it this way,” Janie said. She brandished a slice of toast for emphasis. “Don’t you see? I’ll never be able to have the experience of going to college, and this is the nearest thing to it.

“Besides—I like to be where Tommy is.”

“He’s pretty important to you, isn’t he?”

Jane did not look coy. She said firmly, “He is very important to me.”

But her mother’s remark remained in her mind, and later that week when Jose Iturbi’s niece invited her to a swimming party at Jose’s Beverly Hills house, she accepted for herself and Tommy. They had a wonderful afternoon at the pool, because a heat wave had set in; they had a barbecue for dinner; a party developed afterward, and they danced until midnight.

Then, tired but contented, they set out for Janie’s house in the Valley. Coldwater Canyon winds for a long way up over the mountains, and halfway up the road, empty of traffic except for their car, the radiator cap blew off, the motor uttered a few indignant burps, and froze.

“I guess it was letting the old girl sit out in that blazing sun all day,” Tommy said ruefully. “All the water must’ve evaporated out of the radiator. Shall we start back to Beverly?”

“That doesn’t make sense. Let’s go on to my house.”

“Do you know how far that is?”

He groaned. “Woman, I am swum out and danced out. But—lead on.”

They sang as they hiked. After about fifteen minutes, while they sat on a stone wall to rest, he said seriously, “I’ve liked a lot of things about you, honey, but this is one of the nicest things you’ve done. A lot of girls would be sore at me for what’s happened.”

She was genuinely astonished. “But why? You didn’t know the car would conk out on us. I’m loving every minute.”

After a few moments he reached over and pinned something on her sweater.

“That means I’m your girl,” Janie said.

“It means you’re my girl.”

A car picked them up a few minutes later, and took them all the way to Janie’s house, after they had explained their predicament. It was already one o’clock, which was Janie’s deadline for getting home, so Mrs. Powell had to be roused, and listened sleepily to their story. They had to find a really big can, to put water in, and get out Janie’s car, and drive back to the Chrysler. Then Tommy had to follow Janie back to her house, because she mustn’t go traipsing around lonely mountains alone at that hour.

the “morning after” . . .

Tommy got back to the Kappa Sig house in Los Angeles at four, and did not do so well in the quiz that was tossed at him during his eight o’clock hour. Janie, on the set at nine, looked in the mirror and reflected that she was lucky to be eighteen, so her face didn’t look haggard; and it was good to be a movie star, and in love, and Tommy Batten’s girl.

It was October, with the World Series over and the football season on. In the Coliseum, one Saturday, Janie and Tommy yelled themselves hoarse while SC romped all over Oregon State.

There was no less charm or glamor in the tea dansant that followed the game, at one of the fraternity houses. As they danced, Tommy said, “You’re so quiet. Didn’t you enjoy the game”

“The way it turned out? You know better. It’s just—oh, let’s go out in the patio for a few minutes.”

He followed her, a puzzled frown on his face. “Let’s have it.”

“I’m going away for a while.”

He didn’t say anything to that. She went on: “It’s a big chance for me. Two weeks at the Capitol in New York. Four and five shows a day, but lots of money. If it weren’t for missing you—”

But he was beginning to laugh. “For a minute you had me worried,” he said. “I thought you were going away permanently. I guess I can manage for two weeks.”

“Oh? Well, it’s going to be longer than two weeks. I’ve got reservations at the Waldorf, and mother’s going with me, and the studio thinks I can stay on after I’ve finished at the Capitol. Indefinitely.”

He was not to be fooled. “You’ve got another picture starting the last of November. You’ll be back And New York will do you good. But you be careful in those cabs they don’t care how they drive.”

“You’ll have, fun, too. You know a lot of other girls.”

“That I do.” He grinned at her, and she grinned uncertainly back. She saw his eyes. She read what they had to say. Then she sighed happily and stood up. “Let’s go back and dance some more,” she said.

As they walked inside she added, “At least you’ll get a lot of studying done while I’m gone. I leave you to explore the omphalomesenteric vein to its fullest. In thirty-six hour embryo chicks.”

THE END

—BY ARTHUR L. CHARLES

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948