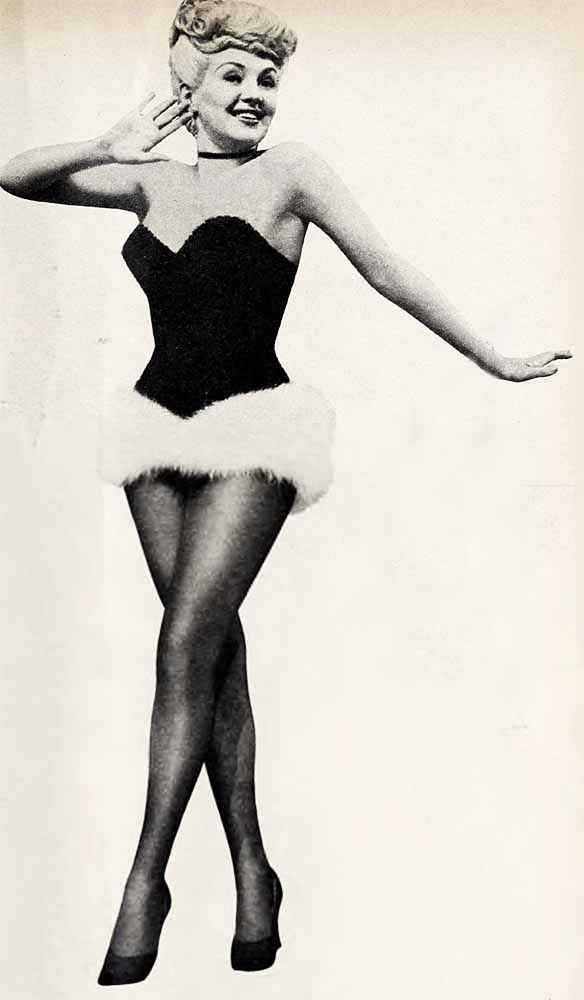

Betty Grable Takes A Bow

“Ten minutes, Miss Grable. . .”

Even as she said, “Thank you,” Betty knew the next ten minutes—before that blue curtain rose—would seem longer than the ten months she had been away. . . .

Betty was in her dressing room, waiting to go on stage for Lux Radio Theatre’s presentation of “My Blue Heaven,” her first public appearance since she’d ended her suspension. In her glittering gown, with her “butch” poodle, as she termed it, carefully coiffured, she looked every inch the motion picture queen her fans always expected her to be. But with each passing minute, she was falling apart inside as she sweated out her performance and the reception she might—or might not—receive, when the curtain went up.

Radio always had terrified her. “What am I doing here, anyway?” she kept asking herself, her heart pounding. “Why am I here?”

Technically, she was there because of her telegram to her studio announcing she was willing, ready and able to resume work.

Beyond that curtain were 1,200 persons, representative of the public that had supported her so well and so long. What would their reaction be?

“I’ll go out there just like Citation,” she was telling herself now. “Win or lose—I’ll arch my neck and take my bow.” Then with characteristic self-humor, “Now I know how Big Noise must have felt when he tried that heavy track for the first time.” The Jameses’ thoroughbred, their beloved Big Noise, had done everything they’d ever asked of him. Whatever the distance, the track—fast, heavy or sloppy—he ran his race, and usually won And Betty was reminding herself now, “Surely I can’t do less than I ask of my horse.”

“What about your public?” her mother had repeatedly reminded her during her suspension. “They want you back. It’s foolish to stop rignt when you’re on top. You can’t quit now.”

No, Betty couldn’t quit now. And the main reason (above and beyond the fact that legally she was committed until 1954 to the studio that made her a star) was her Number One fan, who now waited out front so confidently—her mother. She had always believed in Betty’s talent—believed in her enough to buck all the doubts of their family and friends back home in St. Louis, Missouri, the people who had shrugged away the likelihood of Betty, a taffy-haired, blue-eyed child, with a sunny smile and happy feet, ever making good in Hollywood.

Betty had agreed to go back to work mostly because of her mother, and because of the public, who’d backed her at the box office for so long, and because of whose support she had been one of the leaders among the nation’s “top ten,” for ten years. During her suspension she’d received thousands of letters urging her co return to the screen, protesting the possibility of any other motion-picture personality ever replacing her in the hearts of the writers.

These also were the sentiments of Betty’s studio crew and technicians, some of whom she had worked with since the age of twelve, when she got her first job in a motion picture studio, dancing as one of the chorus.

There was, among them, her hairdresser, Marie Brasselle, who had been with Betty since her first starring picture, “Down Argentine Way.” Likewise her body makeup woman, Bunny Gardell, and Angie Blue, her dance stand-in for ten years. There was the cop on the gate, who had punched her card the first morning she had come through that gate to work in the chorus and who lately had missed waving her red Ford through, every sleepy 6 a.m. and every weary 6 p.m. Betty had missed all of them. She’d spent more time with her studio family than with her real family during the past eleven years.

When Betty finished “Meet Me After the Show” she had worked for nineteen straight months. “I was so tired my whole nervous system was upset. I was cross with Harry and the girls at home. I was jumpy at the studio, flying off at people all the time. That isn’t natural with me. I knew I had to have a vacation, or I wouldn’t be any good to my family—my studio—or anybody. Salary wasn’t the hitch. I just wanted two or three months’ vacation.”

What should have handed Betty some humorous, if ironical, moments were the frequent reports while she was away on suspension that she was bothered by the possibility that the studio was grooming some newcomers to replace her. That there’s room enough for anybody with talent has always been Betty’s belief. And it often has been Betty who has helped others get ahead. She helped short-cut June Haver, Dan Dailey, Dick Haymes Dale Robertson and many others to stardom, by assisting them with a build-up in her films. It was Betty, too, who insisted on Mitzi Gaynor’s being given the oig ballet number in her picture, “My Blue Heaven,” Mitzi’s first big studio break She d seen Mitzi dance, and knew she could do it. “There’s so much dancing in the picture, anyway, a lot of ballet work and I haven’t done ballet for a long time—why not let Mitzi Gaynor do that one?’ she suggested.

Betty never could begrudge a newcomer a break. She’s always insisted she’s had more than her share. She’s often said “I never had too much ambition. It was Mother who set the course—I just went along.”

Perhaps one of the things that made Betty decide to return to the studio was the fact that it would be foolish to waste all the time both she and her mother had put in. . .

I’ve had a good long rest,” Betty said “and actually, I enjoy working when I am working. And when I get back into routine, I work very hard. I work as hard as I can, and do the best that I can, and I’m happy doing it. That’s the way I am.”

That’s the way she has been certainly ior the last twelve years—the reason, no doubt, she has broken box-office records continually.

By the minute now—remembering all this—Betty began to have doubts, to wonder if this return to work was not a mistake. She could feel herself perspiring and her first thought was, “What a state I’m in! I wonder if they’ll be able to tell from the first row.” Later, her mother would tell her, of course. Her mother had always been her mirror, her second set of eyes.

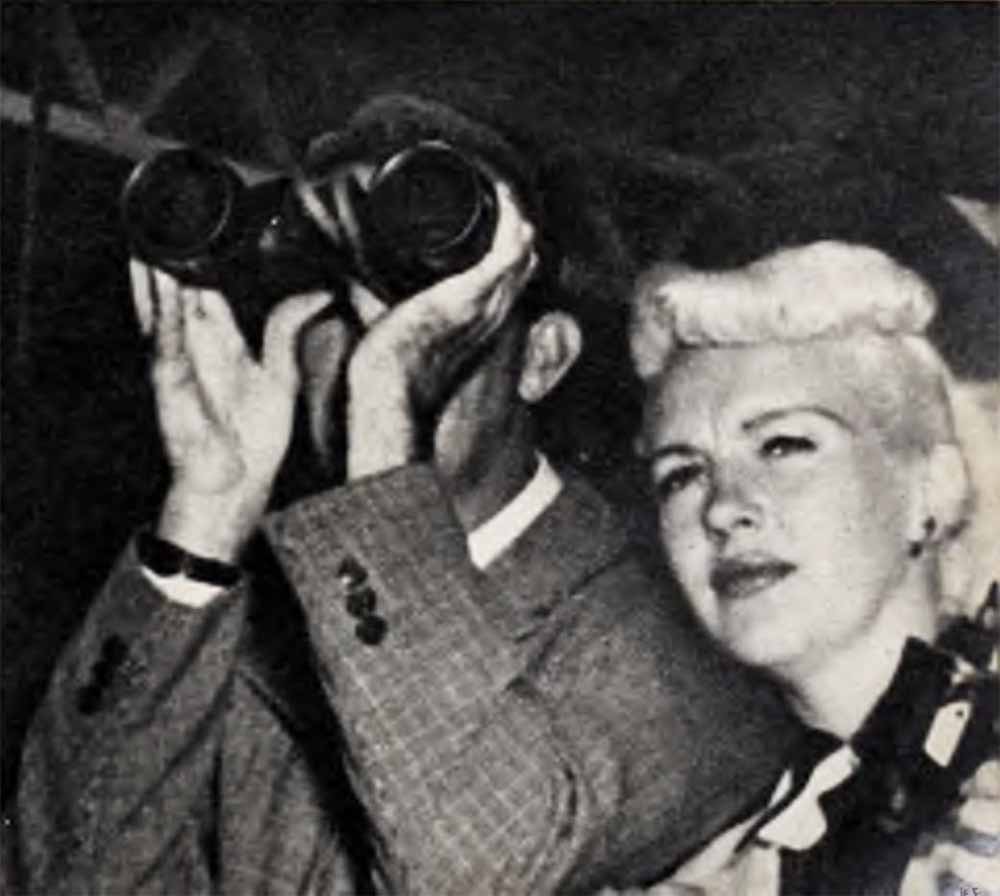

No, she couldn’t quit now. The past ten months had been happy, but they were over. It had been wonderful to be home with Harry and the girls, to decorate the new house, to cheer with her husband at Santa Anita and to go shopping with Vicki and Jessica. It had been hard for Vicki to accept, at first, the fact that her mother was going back to being a motion picture stai “You going back to work, Mommy?” she’d kept saying. “Yes, dear, Mother’s going back to work,” Betty had replied.

I hat is, Mother was going back to work—if Mother could make it to the microphone—and at practically any moment now . . .

Beyond the blue curtain she could hear the director warming up the audience Behind her, the orchestra was warming up too. Then for an electric instant—time seemed to stand still . . .

“Lux Presents . . . Betty Grable!”

The curtain was rising. They were on the air. But they couldn’t go into the first scene. There was not supposed to be any applause but from every side of the theatre, applause thundered spontaneously, as the public got its first look at Betty Grable again. The house came down. And continued coming down. There had been nothing in the history of the Lux Radio Theatre like it. All hands, twenty-tour hundred strong, beat their tribute to a star who, in all her years in show business had never been so touched. She couldn’t believe what she was hearing now . . .

She smiled at them took a shaky stance at the mike, fought back the tears. . . .

The show went on. Betty Grable had come back!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1952

No Comments