Zing Went The Strings Of His Heart

It was late in the summer of 1951. A party was in progress, a Hollywood party for Hollywood teenagers.

Since it was only for the sake of sweet publicity, the handsome, slim fellow of eighteen, who entered the room when the joint was really jumping, shouldn’t have been self-conscious and shy. Not only was he a boy who knew how to beat out boogie with the best of them, but by inheritance he came from a long line of flamboyant people on both sides of his family.

But that inheritance, which had given him temperament and intelligence as well as his striking looks, was exactly what always bothered him socially. His name—John Barrymore, Jr.

John Barrymore, Jr., son of the mighty John and Dolores Costello Barrymore. Nephew of the almost as mighty Lionel and the definitely formidable Ethel. Grandson of Maurice Costello, on his mother’s side—Maurice, the first of the great movie idols—and on his father’s side, grandson, too, of Georgie Drew Barrymore, an idol of Broadway before movies ever were thought of. And before them, grandnephew of the terrific John Drew—and so on and on, back through the generations of theatrical history.

It is a glamorous inheritance, yet a burdensome one, when you’re eighteen and just starting out for Hollywood peanuts, and being starred in your first picture.

Johnny looked quickly around the room. Exactly as he had anticipated, the other kids there were really sharp—a wonder kid like beautiful Joan Evans, a smooth kid like Carleton Carpenter, a cute kid like Betty Lynn. Bob Wagner was beating the drums. Johnny sucked in his breath, suddenly, feeling as though somebody had just dazzled his vision by throwing a handful of diamonds his way. From the far corner of the room a pair of green eyes, as frightened as he knew his own eyes to be, were gazing into his. Feminine eyes, green as a Paris springtime, looking out at him from a face pale as a camellia and as appealing in its innocence.

Johnny stood still, in delighted, amazed shock. How could a face so delicate exist in the hothouse atmosphere of Hollywood? Was he really seeing it? Was there really a girl behind that face?

The hostess swooping down on him made it reality. “Well, all right,” she said, laughing. “Come and meet her.”

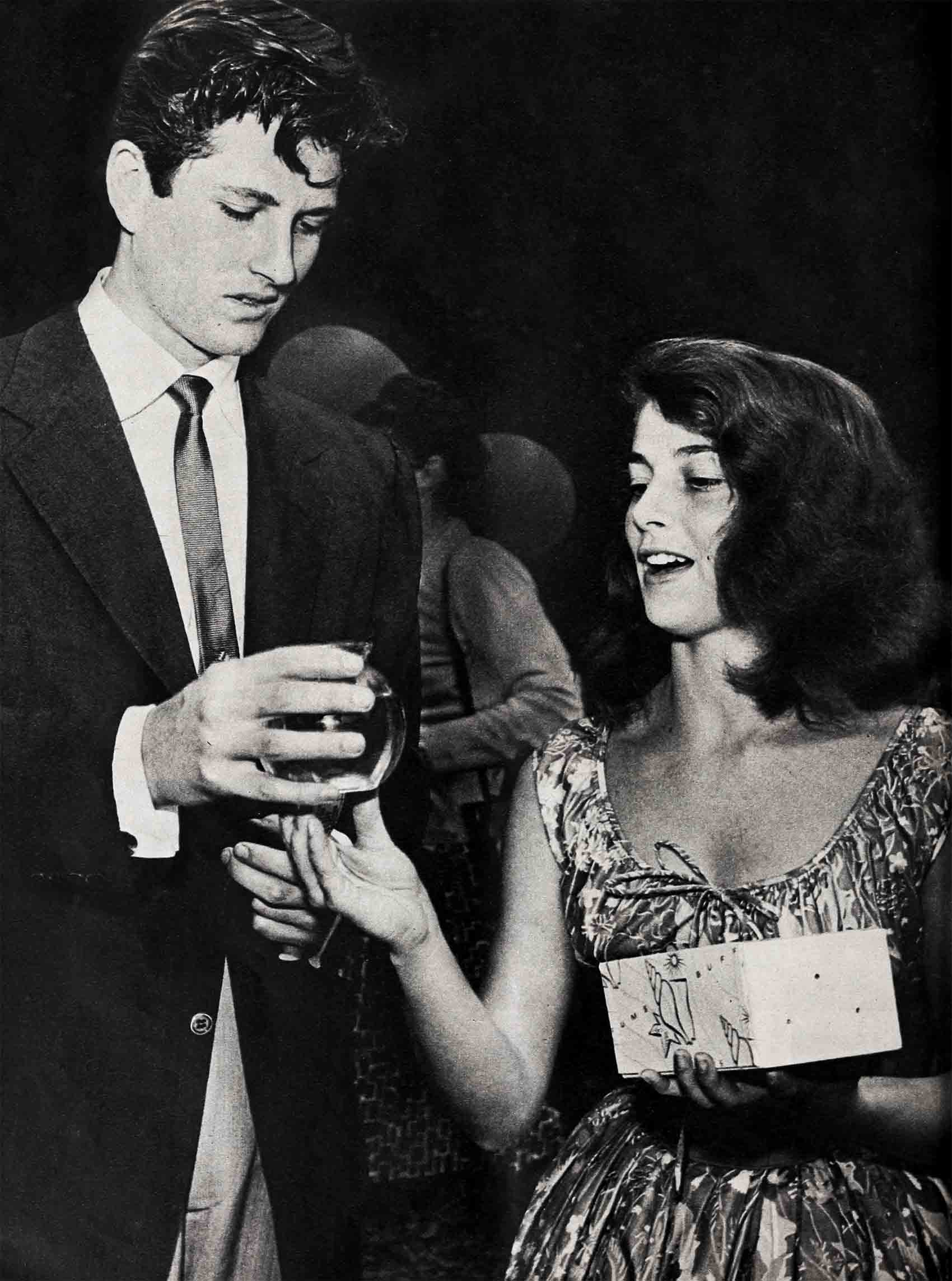

They crossed the room. “Pier Angeli, may I present John Barrymore, Jr.?”

He saw the color rise in that camellia skin. He got the full impact of those green eyes. “How do you do?” she said, carefully, trying not to stumble over the English words.

“How do you do?” He repeated the polite social formula. He felt the tininess of her slender hand in his. He didn’t, of course, add, “I’m falling in love with you.” But that was the way he felt despite as fantastic a set of obstacles as ever set up a hazard for a boy in Hollywood.

Not until later could Johnny put his feelings into words.

“When I’m around Anna,” Johnny says, calling her by her real given name (her surname is Pierangeli, as you probably know), “when I’m around Anna I’m like butter at 900 degrees. She looks at me and I melt.”

Then he grins. He has inherited his father’s sense of humor and his quizzical eyebrows.

“I’ve got nothing but millionaires for competition,” he says. “Millionaires and Anna’s whole family, particularly her mother, and the entire thing of an Italian girl’s upbringing. I know Anna would like to break away a little, have a car and be free to drive it, go out like American girls. She’s twenty now. She’s never been kissed by a guy, unless it was one old enough to be her father, who was giving her a strictly fatherly caress. And I’m pretty sure she’s never had even that, except from her real father. It was only a short time ago that she visited her first night club, and then she was completely chaperoned, and I was not the lucky character who was her escort.”

Actually the lucky escort was multimillionaire Arthur Loew, Jr. He is a particularly nice multimillionaire, heir to all the Loew theatrical enterprises, which means M-G-M too, practically. He’s tall and thin, ten years older than Johnny and Pier, not as handsome as Johnny, but definitely interesting locking, intelligent and generally outstanding. He could be just a rich man’s son but he doesn’t choose to be. There was a time he aspired to be an actor, just as there was a time, pre-Tony Curtis, when he dated Janet Leigh. He could also be a wolf, without half trying, considering his charm, his position his wealth, but he doesn’t choose to be that, either. He is learning to be a producer and it might be that he is actually as shy, as a junior Loew, as John, as a junior Barrymore. Certainly he is very reserved, which is understandable in an executive who probably has met few people who haven’t tried to get him to do them some favor.

Nor is Arthur Loew young Johnny’s only rival. There is Ralph Meeker, who calls at the Pierangeli home as often as Mrs. Pierangeli gives him the chance. There is Richard Anderson, and several other young actors in the same category. And there is David Schine, of the hotel empire. Pier is rarely allowed out unless her mother or her sister are with her. Mama Mia encourages the boys to call on Pier at home. Never alone, but in groups.

“After that first meeting,” Johnny confesses, “I could barely sleep, with wanting to see Anna again. I’d told her a fable at the party about having a friend who was going to Italy and could he call her up to see if he could do anything over there for her. She spoke so little English then that I’m sure she didn’t understand half that I was saying. But anyhow, I got her phone number that way even though it was four days before I had the courage to use it. Naturally I asked her out, when I did call her. Only she left the line to talk to her mother, then asked me to visit her Tuesday of the following week.

“Now I must tell you one wonderful thing about my own mother. She never once laughed at me when I was five and six and would come tearing in, saying, ‘I’m in love with Sally,’ or ‘I’m in love with Nancy.’ I always have been in love with some girl, ever since I can remember. And it wasn’t whatever silly thing older people mean when they smirk about ‘puppy love.’ It was intense and exciting and well—wildly beautiful while it lasted. But I knew from the moment I first saw Anna that I had never felt anything so completely before.

“It wasn’t just because she was the first foreign girl I’d met, either, because I’ve dated a couple of French and German girls. When I went to South America for the film festival I met some fascinating Spanish girls. But never before did I know a girl so beautiful and warm and spiritual, all at once. In one way, she’s a thousand years old, because she grew up in Italy during the war years and in another way, she’s like a tiny child, because it is only since she has been in this country that she has learned to play.”

As preparation for his first encounter with Pier’s mother, whom he visualized as first cousin to the wicked old witch in “Snow White,” Johnny went in for some intensive coaching in Italian. Also to prove that he was a very respectable young fellow, he dressed with startling conservatism—dark blue suit, white shirt, dark shoes, dark, unpatterned tie.

He rang the doorbell and the door was opened by a very beautiful, laughing, young woman. “Hi,” she said, holding out her hand to him. When he recovered from the shock, he learned this was Mrs. Pierangeli. It wasn’t until a half hour later that he found out “Hi” was the only English word she knew. But how she could cook!

Johnny met Marissa that evening, too. Marissa is exactly fifteen minutes younger than Pier. But they barely look like sisters. let alone twins. “Marissa is much taller, and very dark,” Johnny will tell you. “Pier says she feels Marissa understands about love, but she feels that for herself, any real thoughts of love would be premature now. Love, she feels, will come to her when she is ready for it.”

John’s Italian lessons paid off nobly, at least, for asking Pier, “What’s the Italian word for ‘let’s go’?” They would get their heads together over an English-Italian dictionary, one teaching the other. It wasn’t too long before they could even discuss ideas, though when they didn’t agree on some point, Pier would forget all her English and Johnny would forget his few phrases of Italian and they would stare at one another, wild-eyed and speechless. Then, realizing their predicament, they would break into laughter, Pier’s giggles sounding like a chime of silver bells against Johnny’s baritone.

Always however, they had the universal language of music. Anna was allowed to sit at home, playing records, Mamma near by, Marissa across the room and sometimes the baby Pietriza, who had been born such a little while before Signor Pierangeli died, cooing nearby in her cradle.

All the Pierangelis, of course, love opera as madly as American girls love Irving Berlin and Cole Porter. Johnny introduced them, however, to Dixieland and Pier went for it so completely that when M-G-M advised her to take ballet lessons to perfect her posture and balance, she’d dutifully practice for an hour to classical music pounded out on a piano. Then she would beg for just five minutes of Boogie-woogie, and to that she’s improvised dances the like of which have never been seen in any land.

“She made me learn to dance,” Johnny says. “She’d say, ‘You must learn to dance or I won’t go out with you.’ And that threat was enough to scare me into anything, even if every date did mean taking along her mother or Marissa or both.”

One night Johnny took Pier and Marissa to a movie. This was permitted by their mother, except this particular evening, they saw a French movie called “La Ronde.” In case you have missed “La Ronde,” it is what is called highly sexy.

“Pier’s mother still couldn’t speak any English,” Johnny grins, as he recalls it, “but Mrs. Pierangeli sure beat my ears in. Her eyes blazed. Her hands flew. I knew I’d boobed that. I gathered the idea that we’d spend our next date at their house and all I’d be allowed to do would be to sit around and look at Anna. But that is no punishment. I could sit around and look at her the rest of my life and be happy, if I’d only get the chance.”

But constantly, there in the background, has been the tall, wealthy figure of Arthur Loew, Jr. and, of course, Pier’s other occasional dates and the steady Americanization of Pier via two very different girl friends, Leslie Caron and Debbie Reynolds. As a matter of fact, these three are more like girls in any small town than any other trio of personalities in the whole movie village. Pier, since “Teresa,” has been sent back to Europe to make two other films. Most recently she made “The Devil Makes Three” in Europe with Gene Kelly. But separation has only made the girls fonder of one another and when their work does let all of them be at the studio simultaneously, you never heard such giggles, such whispered confidences. Debbie will say, “But he’s a square,” and Pier will say, “Square? But is it not round you mean?” Debbie will say, swooning at sight of Gable or Tracy, “He’s crazy,” and Pier will say, “You mean he is not well in the mind?”

Despite the fact that Pier now lives in a modern, teen-age world, she still retains an old-world charm.

“She’s all dreamer, all spiritual, and at the same time, she’s absolutely motherly,” says Johnny. “For my nineteenth birthday, for instance, I got a present of a whole hundred dollars. I wanted to spend every cent of it on Pier—but what she did was take the hundred dollars away from me, and then dole it out, one and two dollars at a time, so that we could have a flock of dates, Mamma and sister included, you understand.” Two dollars goes a long way at Ocean Park on the rolly coasters and the tunnel of love and such spots.

But a hundred dollars doesn’t go across the table at Mocambo and Ciro’s where Arthur Loew, Jr., equally chaperoned, has taken her. Pier has a lovely time at Ocean Park. She has a lovely time at Mocambo, too. For in her own poetic, sensitive way, she is in love with life.

Arthur came into her life through Stewart Stern, who wrote “Teresa.” He is also Arthur’s. cousin. In fact, sometimes Stewart, Arthur, Marissa and Pier make a foursome, going to movies, going to something as colorful but innocent as the Farmers’ Market.

“Her mother promises that when Anna is twenty-one, she can be freer,” Johnny tells you, his wonderful Barrymore eyes flashing. “She says that then Anna can make up her own mind about love and lots of other things.” His handsome face becomes very thoughtful as he looks into the future. Then he turns and says, with complete sincerity, “Well, I can wait a year. I can wait forever for Anna.”

What he doesn’t know is that at twenty a year is the same as forever, and that at the end of it you may be a very different person.

Meanwhile, he sees Pier every chance he gets. He haunts her sets when she’s working—although he’s been busy himself—making “Thunderbirds.” Ralph Meeker sees Pier, too, and until he settled down quite seriously to Piper Laurie, Dick Anderson was seeing her every chance he got. Still another suitor has come into the picture—hotel heir, David Schine. It has been hinted that Schine has won her family’s complete approval. It has also been hinted that perhaps Pier’s mother will give her daughter more freedom even before her twenty-first birthday. Hollywood’s attitude toward Pier may have something to do with this. The older men of Hollywood, like Spencer Tracy, who is her favorite star, and Gable and the like sum it up, “She makes you feel so protective toward her that a man who would so much as tell her a risque story probably would have his head bashed in.”

Pier says, talking of the difference between life in Italy and America, “American men stay like little boys, always playing games. Even when they are out of college they are still wanting to play games. As for the real boys they are like children. In my country a boy is already a man at fifteen, very serious, very responsible. A girl, a woman, wishes to be in love with a man, not a boy. No?”

It would seem so. Except for one thing. That love stuff. Crazy stuff, love. Particularly at twenty. Unpredictable. But great. Just great—anywhere, at any time!

THE END

—BY WYNN ROBERTS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952