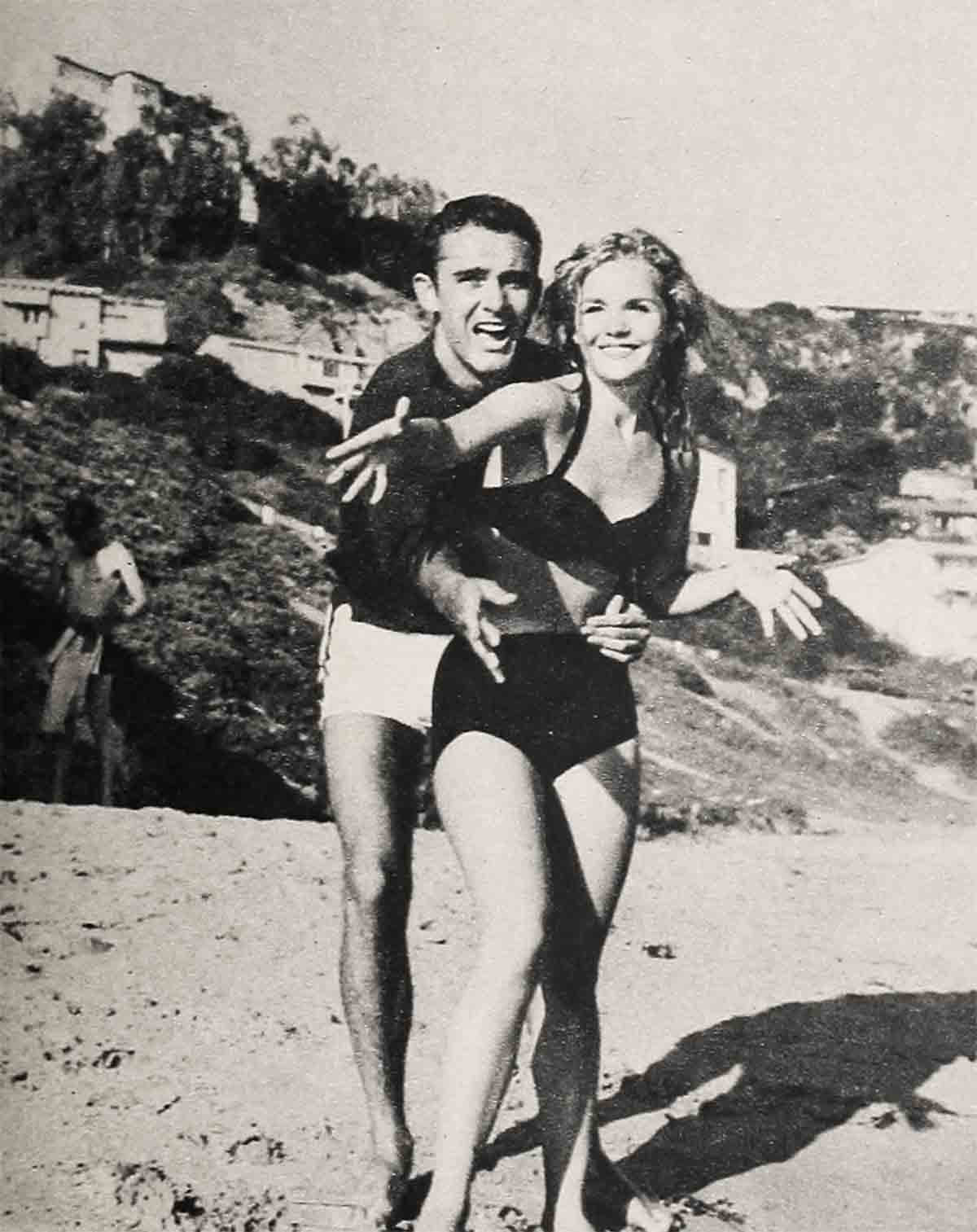

Tuesday Weld Says: “I’ll Lead My Own Life”

It may come as a shock that Benjamin Disraeli was a philosophical forerunner of Hollywood’s most talked about teenager, Tuesday Weld. But when Disraeli suffered the brickbats of his controversial reign as prime minister of Great Britain he held steadfastly to one creed, “Never explain and never apologize.”

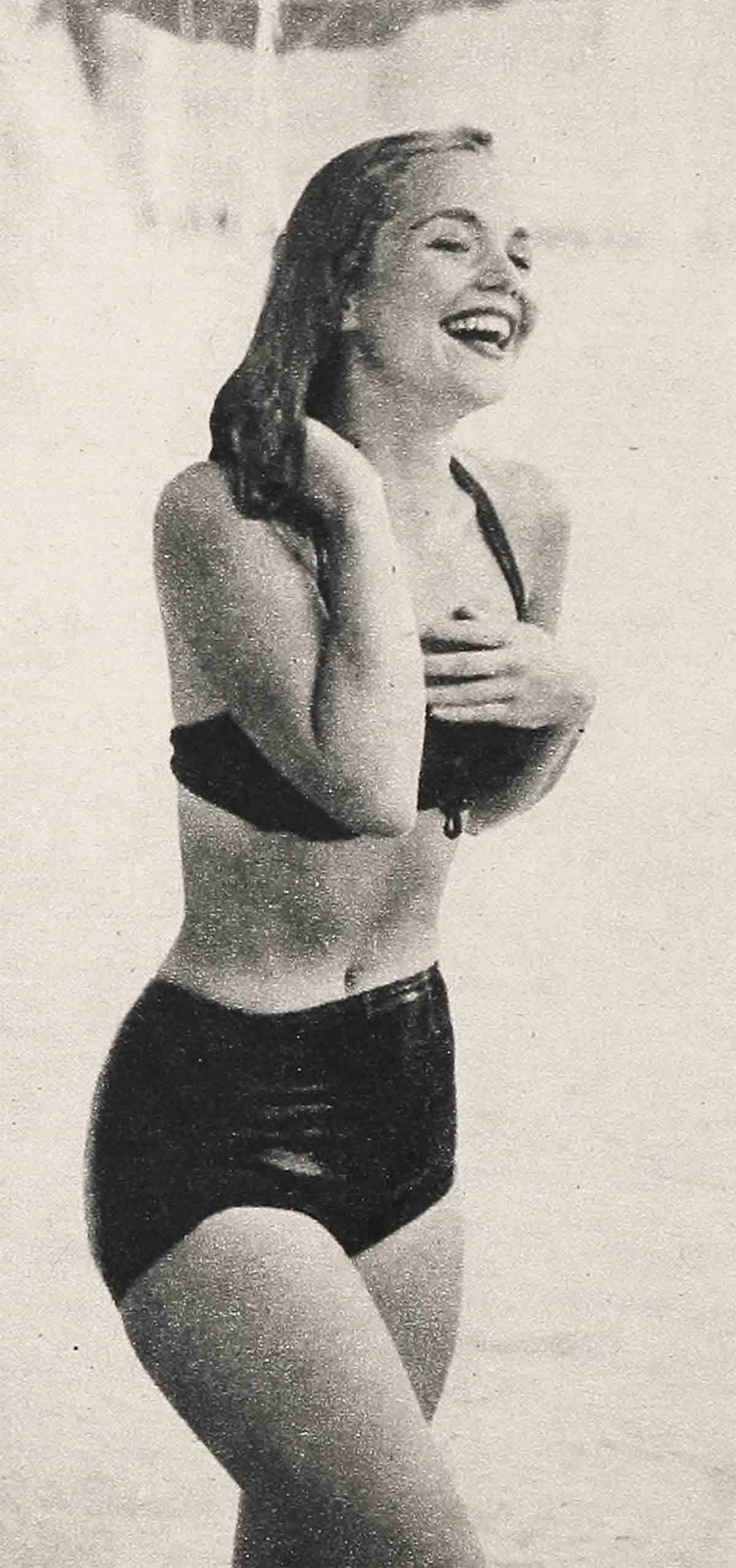

He had nothing on Tuesday Weld when it comes to being an unrepentant individualist. Despite all the handwringing and breast-beating over her allegedly unseemly antics, the most colorful and irrepressible 16-year-old girl to enliven the Hollywood scene in many years remains as sublimely free of guilt feelings as the day she was born.

One evening at the height of public scolding for her precocious habits—her dating of semi-octogenarians like John Ireland, her late evenings out, her asserted beatnik tendencies, her brash unconcern for the forgiveness of shocked elders—I dropped in on Tuesday in her dressing m at a Hollywood television studio.

“What about all these things I’ve been reading in the papers, Tuesday?” I baited her.

“They’re all true!” she laughed with a toss of her golden hair, and went on applying her lipstick.

From her tone it was difficult to tell whether all or any of the stories were based on fact. All that was clear was that Tuesday was blithely unperturbed—not the slightest bit distraught over her mounting notoriety or about what the articles in question might make people think about her.

A few days later, Tuesday and I had dinner in a quiet, softly lighted booth of Edna Earle’s Fog Cutters, a popular Hollywood steak house, and we discussed her runaway publicity more fully. Her attitude had not changed. She still was not interested in proving that there was nothing to atone for in the first place.

“If I spent all my time trying to make people retract what they said, I wouldn’t even have time to sleep,” she dismissed the whole matter with regal disdain. “I figure I’ll prove it to myself without a press agent, without anyone I’m paying to bang people over the head. I figure it should be proved by me because actions speak louder than words—or money.

What it boiled down to, as the evening progressed, was that in spite of all they were saying about her, in spite of all the backbiting and gossip, all the jealousy and resentment, Tuesday still had a firm hold on her own good opinion of herself. That was all that mattered. She seemed to have a sublime faith that as long as her own self-respect was intact, the respect of others could not long be withheld.

She declined to present herself as a young lady without fault, and she declined to prostrate herself in postures of guilt. She asked no apologies on the one hand, and offered none on the other hand. Nor did she feel a pressing need to launch a be-kind-to-Tuesday movement.

“Even if what I do doesn’t seem to make much sense,” Tuesday shrugged as the waitress arrived with the salad, “I’m not hurting anyone when I’m doing whatever it is they say I’m doing. The only person I might be hurting is myself, and that’s my own decision. If I can’t hurt myself, who can?”

The ease with which she talked about it seemed to back her claim that she wasn’t bothered by the publicity which had made her the talk of Hollywood and doubtless a conversation piece across the rest of the land. She treated the situation with a genuine unconcern remarkable for a girl so young.

In fact, she even laughed at the determined whispering campaign to the effect that she’s no more 16 than Jack Benny is 39, that in reality she is 19 or 20 if she’s a day. Far from being outraged by slanderous suggestions that she might be a teenage impersonator, Tuesday delighted in the flattering implications of this spite. She clearly ‘enjoyed the fact that so many of her peers considered her so adult that they couldn’t believe her age. She was at that stage of life where it was exciting to be thought older than she was, and she was in no haste to dispel this myth.

She would only say with a sly wink, “I am so not 19!”

California school authorities, however, are privy to her birth certificate, and they are sufficiently convinced of her tender years to see to it that she is treated like any other juvenile in the state when she is working. Tuesday always has a tutor on the set, even as Natalie Wood and Sandra Dee had until their 17th birthdays. However, if Tuesday’s detractors preferred to ignore this documentation of her age, she was of no mind to spoil their fun.

“I’m beginning to think I’m much older than I am,” she laughed. “I turned my ankle while dancing last week, and you know what the doctor said to me? He took an X-ray of my feet and said that my bones were not 16. He said my bones were the bones of a 19-year-old girl. So there you are, see? My feet are 19 and my body is 16.”

Yet Tuesday’s rise has been so swift and controversial that inconsistencies do not seem to discourage her mushrooming taskmasters. The same people who express skepticism about her being a bona fide 16-year-old girl are the first to deplore her social life by accusing her of a predilection for dating men much too old for a girl of 16. But even this failed to make her squirm about her much discussed friendship with 44-year-old John Ireland. She felt that it needed no justification, on the basis that having done nothing wrong in the first place, there was nothing to explain in the second place.

“It’s my life,” was Tuesday’s biting reminder to those shedding crocodile tears about her supposed peril in the company of a man Ireland’s age. “I was born with it, and I’m going to lead it. In simpler terms, you have only one life, so live it.”

While her words breathed defiance, her attitude was more of amused indifference.

“Beat The Press!’ she quipped good-humoredly. “That’s the new TV show I’m going to do.”

Those who know Tuesday are aware that she is not remotely a beatnik. Despite this and despite the fact that at the Fog Cutters she wore a lovely, ladylike cocktail dress, sheer stockings and smart patent leather shoes, she showed no urge to disprove her highly exaggerated beatnik publicity or to explain that for a brief spell a long time ago, she had explored, but never had embraced, the beat world.

She even turned aside my personal affirmation that she was not one to parade in the funereal garb of the beat generation—black sweater, black stockings and black capri pants.

“You’re too well-groomed,” I paid her a deserved compliment. “Everything is in just the right place. Your hair is on top of your head!”

“Today!” she exclaimed mirthfully.

“Anyhow,” I persisted in her defense, “I’ve never seen you dress as a beatnik.”

‘But with her girlish mischievousness—so often mistaken for brazenness—she declined my kind offer of a whitewash.

“Occasionally I do!” she protested in mock indignation. “Now wait a minute there! What are you saying? Lies! Lies! All lies!”

“Well, at least you don’t go to beat dives,” I said. But again, in a renewed outburst of deviltry, she passed up the opportunity for absolution.

“Oh I don’t know,” she grinned. “I do once in a while. I have to keep the publicity going. you know. I can’t drop the whole thing. After all, they make it sound so interesting. I have to see what this is about now.”

Tuesday had no intention of depriving her would-be tormentors of their pleasures, let alone begging mercy. She was sublimely content to let them believe what they wished. She argued only one minor point in her defense—that whatever madness might be attributed to her, there was at least some method to that madness.

“There’s always a reason for what I do—if I really did it,” she chided. “It might be a lurid reason, but you can be sure there’s a reason.”

Many of her friends were greatly upset about the tongue-lashing administered recently in a nationally syndicated gossip column. They were up in arms in Tuesday’s behalf because she had been called a bad example to other teenagers. They all wanted blood or retraction. But not Tuesday. She refused to get caught up in a whirlpool of righteous indignation.

“I don’t do a darn thing,” she sighed a little wearily. “All I do is sit. I don’t even read the papers. All these people go storming around about what’s been said. I don’t even know this columnist. All of a sudden she started on this hatred kick and kept it going for about three months. Then she stopped.”

Nor was Tuesday even willing to take umbrage at stories of her allegedly temperamental behavior on the set of “The Many Loves Of Dobie Gillis”. Instead of giving the lie to the rumors whizzing around the town’s ice cream parlors, Tuesday was the first to admit that she was indeed capable of temperament—and she was not contrite about the fact, either.

Most people accused of less than saintly conduct invariably fall back on their defenses and cry, “Who me?” Not so our forthright Tuesday. No such injured innocence was forthcoming from her. She agreed in a flash that all anyone has to do to bait her is to be a bore or a cold fish.

“You’re darn tootin’ I get ornery, impatient and snappy when I’m disappointed in people,” she said. Her tone implied there was no other way to.act. She felt no more remorse about blowing up under provocation of asininity than she would at bleeding if she were cut. She regarded both as simple cases of cause and effect.

However, Tuesday did ridicule the proposition that her willingness to blow her pretty cork -on occasion meant that she was anti-people or even that she was anti-social.

“It’s not that I don’t like people,” she smiled warmly. “It’s just that I wish there were more people to like. When people give me a bad time or talk behind my back, I can’t really say I dislike them. I can’t say I hate them. That’s much too good to spend on generalizations. You save your hate for something juicy. I’m just mainly indifferent about people who don’t inspire or stimulate me.”

Basically, Tuesday’s flashes of petulance well might stem from her annoyance at her own basic shyness.

“One of my biggest battles—or fears—is trying to relate and open up to someone who is obviously very shy,” she said earnestly. “I’m very shy. People who are shy make me twice as shy. I don’t know what to say. I clam up. I feel rather inadequate. It’s odd. Gregarious people bring me out of myself. Yet I can’t bring themselves. It other people out of shouldn’t be that way.”

Meanwhile, what frequently is normal and uncontrived for Tuesday seems like a shocking escapade to others. One reason may be that she lacks the usual fear-ridden approach to Hollywood and stardom, She balks at tribal mumbo-jumbo on the set just as much as she refuses to submit blindly to arbitrary social rituals. For a girl of a mere 16 summers she has developed a very low tolerance for sham—in herself as well as in others. This is an attitude that was certain to bring her into disfavor with self-righteous and self-constituted morality monitors—and indeed it has.

“People seem to expect you to play games all the time,” Tuesday explained as she carved her succulent cut of New York steak. “To me that’s living a lie. You know what I mean—they’ll like me better if I do this or that and don’t do this. What’s the use of pretending you’re something you’re not—for a boy friend or for anyone else? I don’t like games, that’s all. Tell the truth about things and feelings. That’s what I happen to believe in.”

Tuesday’s fork dangled mid-air as she developed the contention. Her manner underlined the very point she was making. She wasn’t talking for effect. The words tumbled out—and she didn’t stop to screen them, to decide whether her thoughts would meet standards of safety and conformity before expressing them.

In my many contacts with Tuesday I never have found her sullen, unreasonable, affected, uncivil—or dull. Yet she did not choose to challenge the grumblings—among those who do not find her sufficiently subservient—that she can be a very moody young doll.

“How could I try to pass myself off as an actress. if I were otherwise?” she wanted to know.

Even so, Tuesday was forced to admit, sheepishly, that she does try not to inflict her darker moods on innocent bystanders.

“I save my brooding,” she smiled, owning up unabashedly to a mid-Victorian conviction that one should show consideration for the feelings of others even if it hurts. “I cover it up. Then I’m twice as moody when I get alone, or something like that. Of course, there’s a point where moodiness is inescapable. I think it’s all right to be in any mood as long as you’re not hurting anyone. If you feel like standing on your head, then by all means stand on your head.”

A second later she blurted out an impulsive disclaimer of nobility.

“If I could only practice what I preach!” she sighed.

Frequently an effort to come to honest terms with a situation is interpreted as temperament. It is not unusual for Tuesday, with her predilection for living life as it presents itself; to be caught in the cross-currents of such opposite views. There have, for instance, been some rumblings of late that her abbreviated telephone conversations are the actions of a spoiled brat. Tuesday wasn’t the least bit defensive about it.

“I have to take some time out to. be alone,” was her simple explanation. “I never answer the phone anymore because I’ve been so busy that I’ve just got to make time for myself to do things I want to do. Why waste time talking to someone on the phone for a half-hour and saying nothing? You know, it’s gotten to the point where it takes about 15 minutes just to say hello!”

She proceeded with a mirthful rundown of the platitudes that are trotted out in typical time consuming telephone chatter.

“Where have you been?’” Tuesday recited sardonically. “ ‘Where did you go last night? What were you wearing? What was she wearing?’ Then they go into who they’ve seen lately, and who I’ve seen lately. Suddenly an hour has gone, and the conversation ends with, ‘Well I’m working all this month. I’ll see you next month.’ The phone should be used when you only have something definite to say.”

Tuesday obliged with a blunt social case in point.

“If someone calls me and asks if I’d like to go with them to an elegant party that night, and I don’t feel up to it, I just say plain no and goodbye,” she said without compunction. “I used to make a lot of excuses. Thank you. It was so nice of you, and so on. Look at all that good time gone!”

She paused and broke into a smile.

“You’ve begun to know my big bug this year,” she grinned.

Tuesday has taken the serene position that it is for others to judge her. actions if they must, and for her to know if any of the legends about her have any truth to them. But entirely aside from whether censure is merited or not, she did provide dramatic insight into her behavior when she blandly confided that she was no stranger to a thing called loneliness.

“I think the main sickness that everyone has is loneliness,” she ventured her diagnosis with the certainty of a doctor prescribing for the common cold. “But loneliness is interpreted as meaning many different things. Like being moody. Like being an extrovert. Any and all of those things come from loneliness. I think that loneliness is the greatest torture a human can have.”

It is no wonder that with such perception even her admirers might express astonishment that Tuesday is 16 years old.

“Rejection, insecurity, it all stems from loneliness,” she spoke as if quietly relieving old pains. “If you’re not insecure it means someone has made you secure, and something has happened that you shouldn’t be lonely.”

Her face fell reflective as she pondered for a moment, and then she continued.

“When I feel lonely,” she said softly, “I suffer. I walk and I think or I toss in bed. No, I don’t call anyone. Not when I’m really, really lonely. I don’t. When you’re just surfacy lonely you can call up someone and it’s over. When you’re deeply lonely you can’t be satisfied by calling up a person because it decreases in value.”

Tuesday did not discuss her loneliness to mollify her critics, however. She was not even convinced that anyone needed to be mollified—any more than she was convinced that she was being maligned.

“I can’t really argue the point too much,” Tuesday insisted. “I don’t understand what’s to be misunderstood yet. Maybe if I understood that, I could say that they misunderstand me. I just don’t understand the basic thing yet.”

Is it true what they say about Tuesday Weld? There would seem to be four verifiable facts about this 16-year-old individualist—that she is complex, that she is enchanting, that she is worthwhile, and that she is genuine. For most people, that will be sufficient truth.

THE END

—BY MARK DAYTON

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1960