The Dane Clark Takes Over

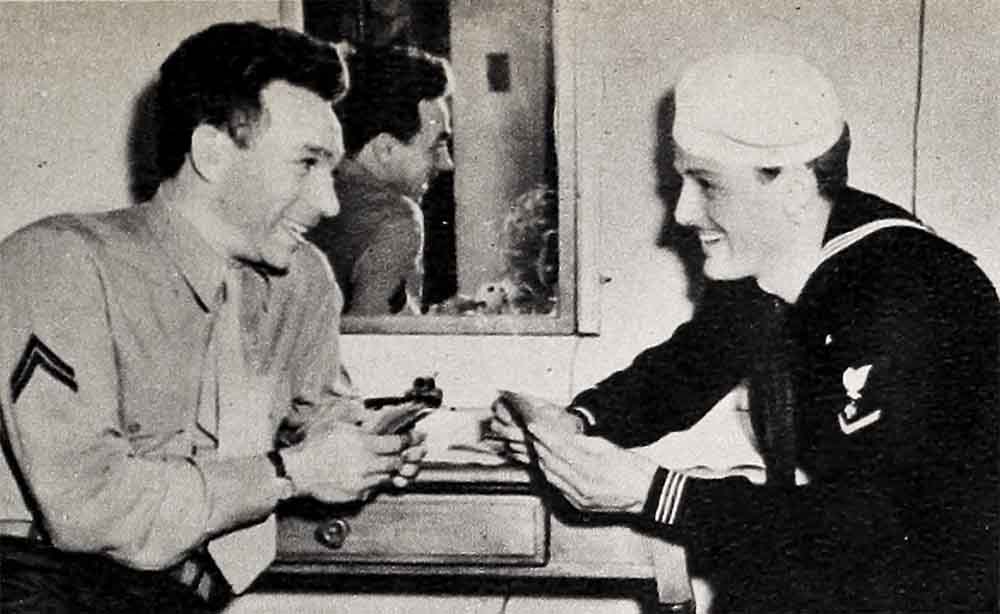

The place is a neighborhood movie in Los Angeles. The picture is “The Very Thought Of You” with Dennis Morgan and newcomer Dane Clark playing a pair of fighters on furlough. . . .

The scene is that one in which Dane, a kind of jet-propelled romanticist, tells Faye Emerson, the sub-deb he sights and eventually will sink, that they are about to go dancing. To deploy any objections she may be about to make, he picks her up and prepares to carry her out her bungalow door. On the threshold Faye, a victim of arms and the man, asks helplessly, “What would you do with a guy like this?”

“Don’t answer that, girls—”

The warning comes in a feminine voice, not from the screen but from the theater, and precipitates a bedlam of shrieks and “Ohhhhs.”

This will give you an idea what’s happening these days when the public meets the Clark who isn’t Gable. Since “Action In The North Atlantic,” this young man hasn’t had much time for inaction.

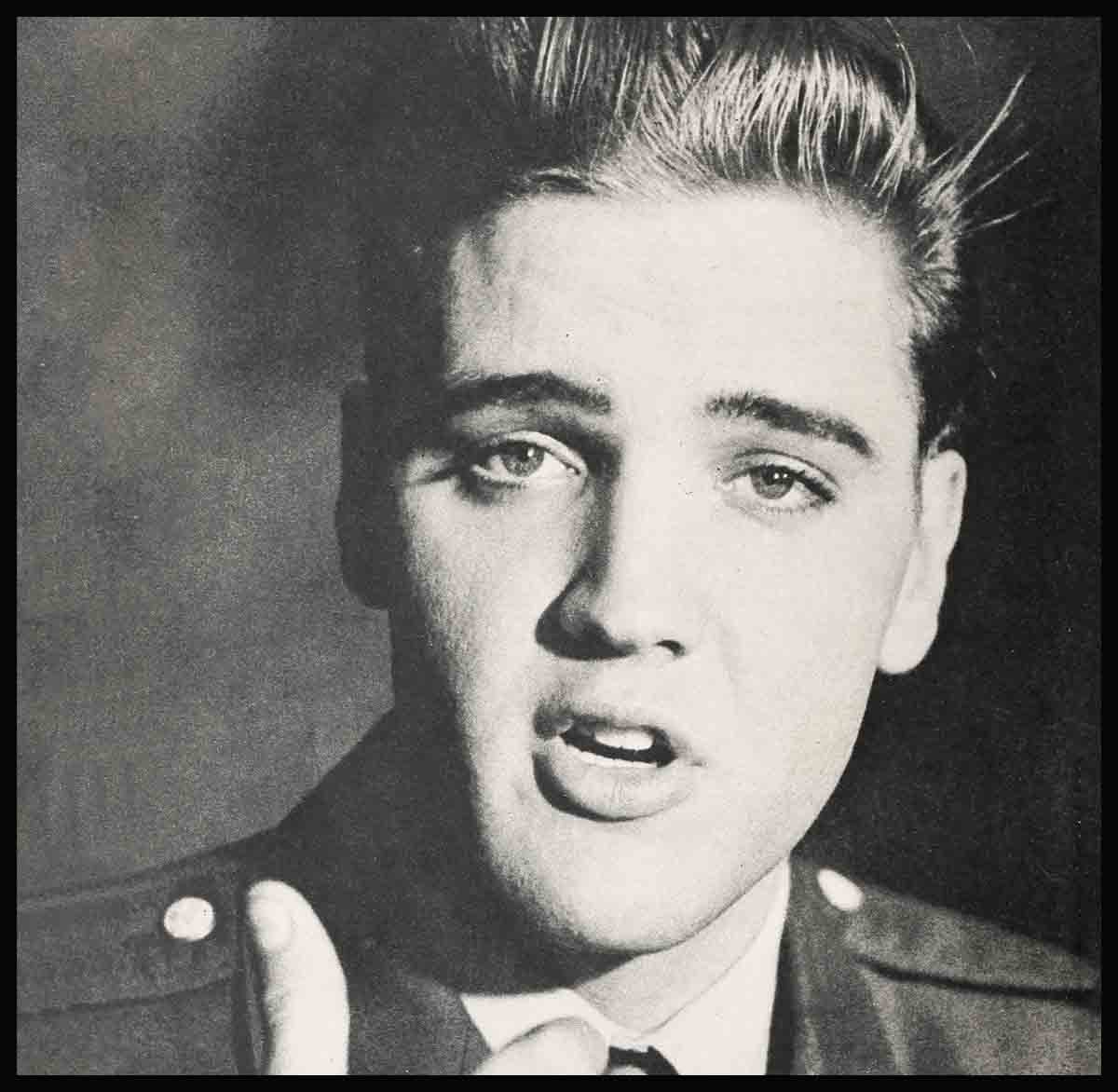

Dane is one of those fellows you feel as if you’ve met before, but know you haven’t. He’s definitely not pretty, even his wife Margo will tell you that. He has dimples, but he also has the kind of face that looks as if no great harm had been done by a GI haircut. Outside of that, he is best described as a fellow who must be making Bogart, Cagney, Tracy, et al, look back ten years or more and sigh, “Those were the days!” Force and cockiness, an inescapable quality as an actor, he has them not to get, but now, with the driving power of youth behind them.

Off-screen he is a young man with a grin, and with a personality like the shortest distance between two points. Meet Dane on the screen—and you know you’ve been in

a scene. Meet him off-screen—and you know you’ve been in a conversation. He talks pungently, positively and perpetually, with a talent for both humor and argument. What, or whom, he likes is “fabulous”—what he doesn’t like “stinks.” He doesn’t want his enthusiasms cheated, or his un-enthusiasms to get anything that isn’t coming to them.

As a quick example, there is the view he takes of those actors who treat movie-making as a sideshow to New York.

“What’s their great passion for New York?” he asks. “I was born there, I got my start there, but I’m not aching to go back. The town tore my heart to ribbons . . . Most of the people who go around talking about New York now weren’t doing anything back there but breaking their necks to get out here—the same way I was. I hate pretense.”

The disinclination to mince talk or time was congenital. While there is no available record of the infant Clark’s first spoken word, we can imagine when and how it occurred: There he is on the first day of release from his crib, toddling to a window, looking the world square in the eye, and saying, “Well—?”

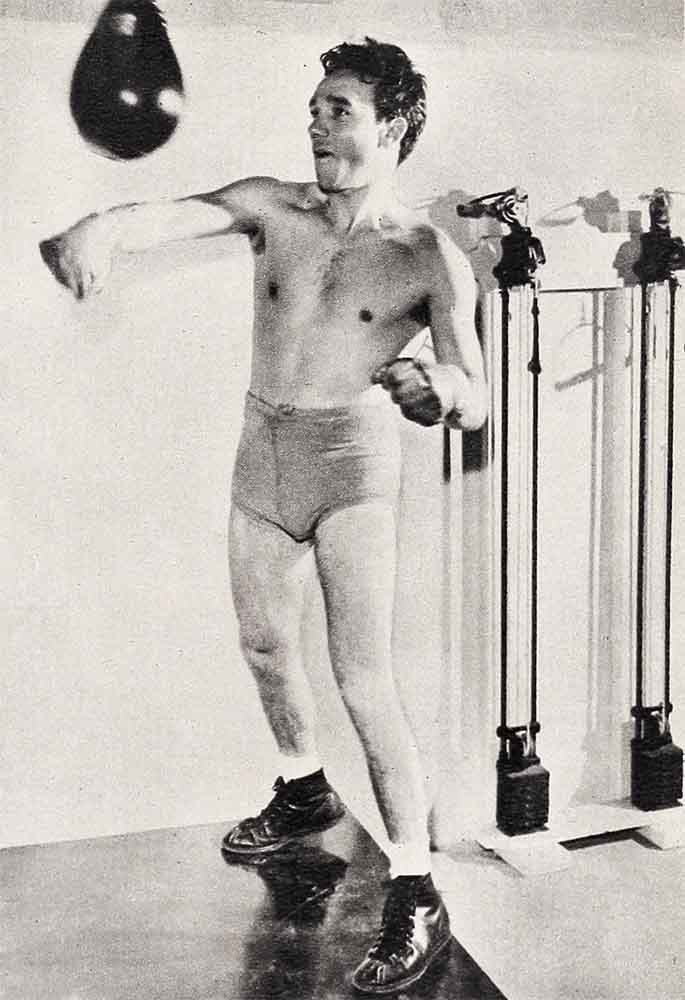

Without waiting for an answer, he dispatched his childhood in a hurry. “Nothing but work,” he sums it up with a grin. “I even worked when I played. My dad owned a sporting goods store and I played all the hard games—football, baseball, boxing—the kind you have to knock some guy in the head to win.”

At the end of high school he had a professional ball contract with a minor league. Then he became a middleweight fighter for a while (his name was Bernie Zanesville, those days) but with no desire to get punch-drunk, decided to study law. He worked his way through the necessary courses at Cornell and St. Johns and finished with the start of the depression. It didn’t seem like a propitious time to hang up a shingle, so he marked up the law courses to experience.

“I never look back . . .” which, come to think of it, is as smart a way of assuring forward motion as any we know.

A little uncertain as to what next, he investigated the prospects and pursuits of a so-called Bohemian group of self-rated artists, writers and actors—the kind neatly catalogued by Charles Coburn as “amateurs teaching amateurs to be amateurs.” Only Dane hadn’t met prexy Coburn at the time. He soon discovered their contempt for really successful artists, writers and actors and decided he wanted “cabbage—not hunger.”

His first objective was radio, which he took the way MacArthur took Manila, with well-placed artillery.

“The answer, when I tried getting an acting job was, ‘Sorry, we don’t happen to have a script we can use you in now.’ So I went home and wrote ’em three radio scripts and took them down to the program department. They wanted to buy all three. So I picked the scripts up off the desk and said, ‘Sorry, but I go with the scripts.’ ”

“Show me on this page where it says you can act,” said an exec.

“I could show him because I’d only written in parts I could act. I got an audition, and after that they put me to work.

When he felt an urge for a visible audience, Dane joined both the Theater Union and the Mercury Theater, playing in the companies of such stars as Tallulah Bankhead and Orson Welles. From there he went on to Broadway, to follow Burgess Meredith as George in “Of Mice And Men,” to play Baby-Face Martin in “Dead End,” the communist playwright in “Stage Door,” and other roles in “Golden Boy,” “Sailor, Beware,” and MacLeish’s “Panic.”

It was during this time he picked up his slight tinge of Odets, of whom he says, “Odets didn’t create anything new. He took something that was there all the time. He knew that men are not all Greek gods, golden-haired and seven-feet tall, with nothing but classic emotions. He found that sometimes they’re short and sweaty, with hunger and ugliness mixed in with the good in their souls. Odets took the music of people as they are—and gave it back to the people.”

In spite of what some young men would have considered a thriving career, the “haphazard economics” of the legitimate stage eventually convinced Dane there must be something better—and it could be Hollywood. His trip across country and into the western scenery was something he doesn’t want to forget. Although he drove it with his “fingers crossed,” he also drove it with golf clubs and swim trunks in the car and stopped off frequently to use them.

It took almost a year in Hollywood for the Clark personality to really get going. Following the usual procedure, he got himself an agent, a good enough one—and a succession of insignificant parts: “Everything I did before ‘Action In The North Atlantic’ was a walk-on.”

It is interesting, and typical, the way this first good part was snagged:

“I was getting tired of going into casting offices to have some character make a private evaluation of me, then put me off with that ever-lovin’ ‘We’ll call you—.’

“I was in Warner’s casting office one day when Producer Jerry Wald walked in. I heard him say he still hadn’t found the right fellow for a part in ‘Action In The North Atlantic’ so I walked over and recommended myself to him. He’s a very courteous guy—he listened, then said he’d call me.

“The fatal words got me. ‘Why call me when I’m already here?’ I asked him bluntly. ‘You’ll do twenty-five tests before you’re through—what’s the matter with doing twenty-six? So I may stink, but what right have you to decide I will without giving me the chance to prove I stink?’ ”

Producer Wald knows his man when ”he finds him. The missing character for “Atlantic” had a scene involving the same basic principle Dane had just demonstrated, the right of every American to. speaks his mind.

The screen test emitted no odor except that of success, and when Dane spoke from the screen as a member of the Merchant Marine who refused to take his ship out to sea, his words carried enough conviction to be reprinted in maritime journals all over the country.

His next appearance was in “Destination Tokyo.” ‘Most of his roles have been in uniform of some sort.

“All the make-up department has to do with me is give me one stripe more or less. . . .

“They put me into ‘The Very Thought Of You’ just for laughs. I was grateful for the fan mail on that one—looks like maybe I’ll spell off as the underfed Jack Carson. Then came ‘Hollywood Canteen’ and ‘God Is My Co-Pilot.’ ”

Not yet released is the serious drama, “This Love Of Ours,” the story of blinded war hero Al Schmidt, with John Garfield playing the Marine, and Dane as his buddy. Garfield is Dane’s idea of a completely honest thespian.

If he could pick his own leading woman tomorrow, it would be Olivia de Havilland. Which brings up the subject of the kind of women he likes best—“female women.” Dane says he learned about women from one of the species who kept him very unhappy “expecting her to make sense.”

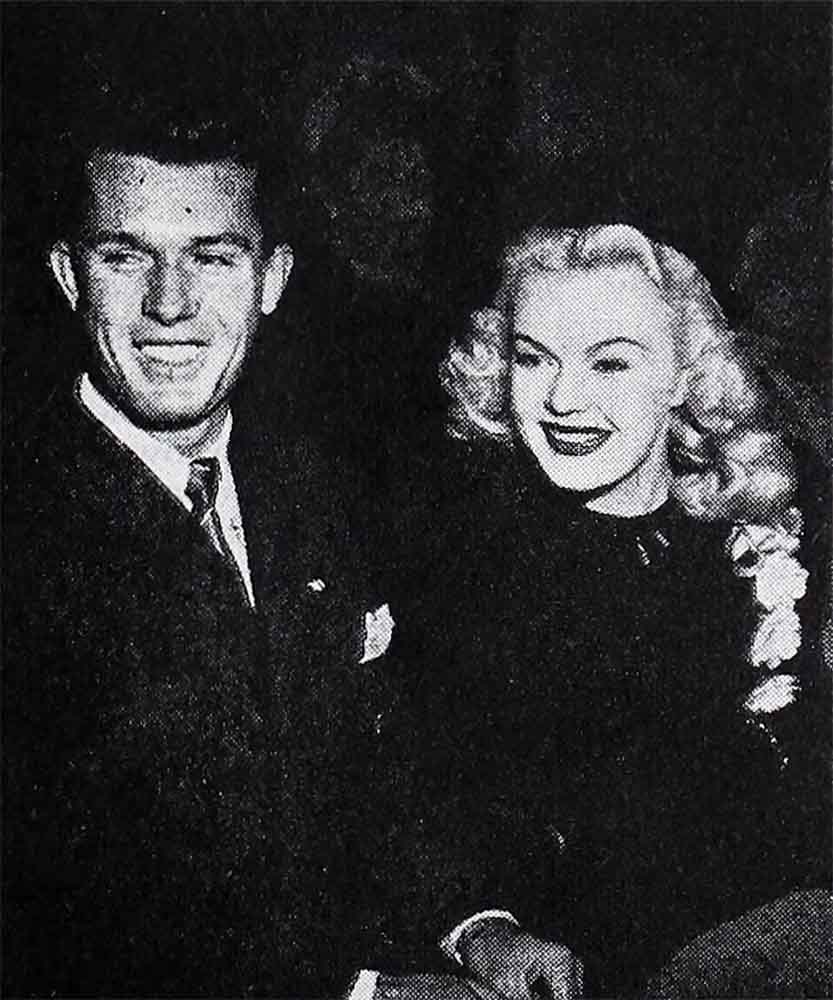

“I know now that to enjoy ’em, you mustn’t expect too much of ’em,” he grins. It’s possible he’s merely ribbing on that one, however, for the next minute he’s bestowing all the complimentary adjectives in the book on Margo, his wife of four years, which is plenty long enough for a husband to know whereof he speaks.

“She’s keen, live, intelligent, alert—and wonderful,” he adds to clinch it. “Flaming red hair and temper to match, and very blue eyes. A top designer and a fine pianist, studied in Paris. I’ve kept her pretty busy the last couple of years just cheering me on in my career but I suppose some day she may want to get going on something of her own again and if she does, well that’ll be me applauding, same as she’s done for me.”

They met in New York and it took Dane a year and a half to think up something fancy in proposals. He doesn’t remember now just what he said, but he does remember why he said it. Margo went home to visit for a while—and that did it. “It may not have been original,” he says, “but it was concrete—I found I just couldn’t do without her.”

He still feels the same way about it. During the Christmas holidays when his wife took a trip East, he was “the lone-somest guy in town. I spent Christmas and New Year’s at the Canteen. The only way I could feel any better was in trying to do something for a bunch of fellows as low as I was.”

In this era of housing shortage, the Clarks live in a house in Coldwater Canyon. “Someone dug it out of the moss when things got bad. It’s Cape Cod outside, and hasn’t got a creature comfort inside—including plumbing.” They rent it but Dane is already longing for something with roots. “Guess because I’m a city fellow I’d like to know what it is to have a little piece of land to call my own.”

Margo puts up with his hobby, which is saving old coats and jackets he is always “going to have fixed up and wear sometime,” patiently moving the bulky collection wherever they go. She also knows when he is immersed in a book he is apt to bring it to the table and read all through the meal, and beats him to it by grabbing off the latest best-seller, herself.

“I subscribe to just about everything I can,” he explains. “I try to keep my reading comprehensive, the new things and a good selection of the old ones. You get rather personalized in your reading when you’re acting, always feel you’re on the verge of finding the perfect story and trying to see yourself in everything—”

The most treasured possession in the Clark household is a small and bedraggled red rubber kewpie doll, ten-cent-store variety, which Margo bought for him as an “opening night gift” several years ago. The play was a hit and although the kewp has long since lost its squeak they’ve kept their luck, and now wouldn’t think of going any place without it.

Good music and well-blended colors give him “a mental yip.” Music, to thrill him, must be “good of its kind,” and the kind can be either classical or popular. He has a collection of Flamenco gypsy records, and was a Calypso enthusiast “way back when they were Cuban street-singers, Homeric rather than Andrews Sisters in type.”

His best trait, he thinks, is a passion for paying bills—he can’t bear to owe anything. His best and most enjoyable fault is an aversion to wearing anything for lounging purposes “except just enough to be decent.

“I’d like to learn more about the effete way of living—take up tennis and some of the gentler games, where you don’t have to loosen anybody’s teeth. I might even write a little poetry—oh, you think I haven’t got any poetry in my soul? Well, I have—it doesn’t have to be about violets and triolets, does it?”

In the meantime, he’ll keep on taking his hurdles wisely, honestly. And some day as a matter of course the columnists will be calling him “Warners’ Great Dane.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945

No Comments