Of Howard Duff And Stuff

Take it straight from headquarters, the only man who could crack this case wide open is Sam Spade, Private Eye of the Airlanes. But good Sam vacillates between duty and despair when it comes to a public grilling of Howard Duff. It so happens these two gentlemen are one and the same.

Rugged, ruthless Sam, backed by 243 fan clubs who have taken Spade to their hearts, has been forcing fast talk since July, 1946. Quiet-mannered, introspective Howard is still so new to the film firmament that he has patient paroxysms when he is put on the spot to talk about himself in an interview.

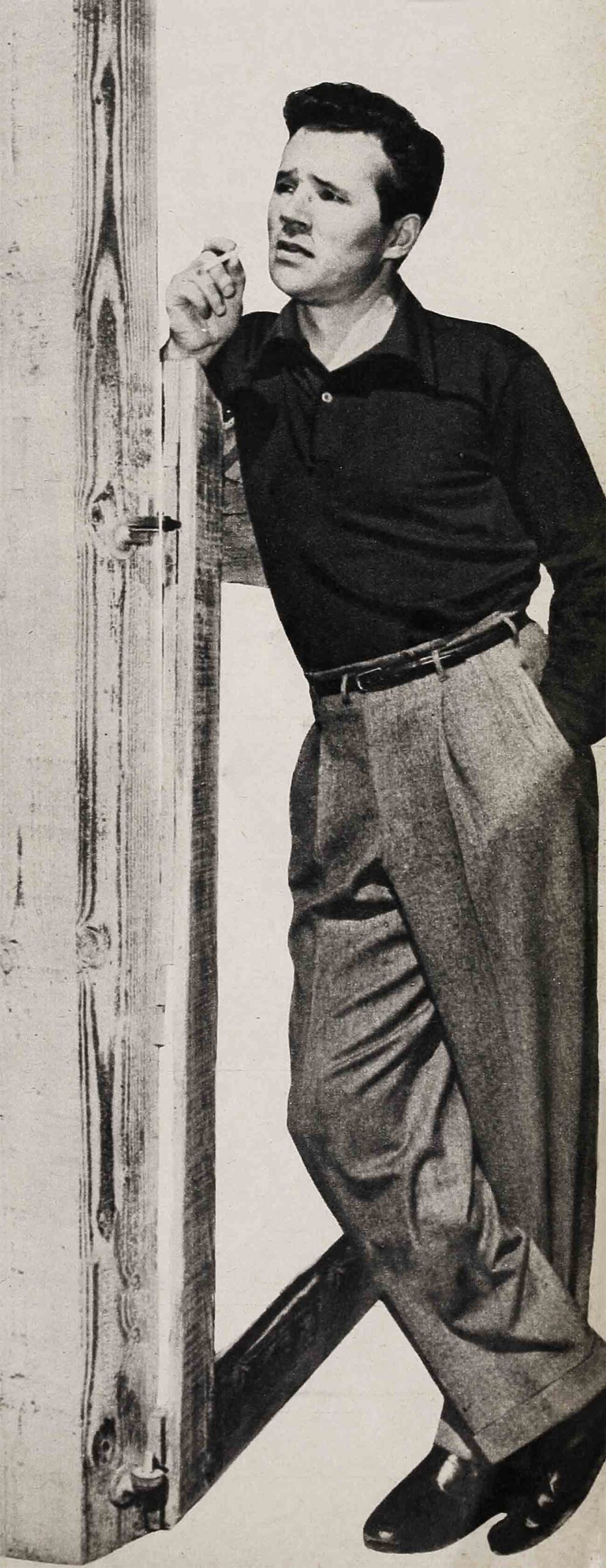

“I’m a voice who suddenly found a body on his hands,” muses the man everyone loved and “loathed” in UniversalInternational’s “Naked City.” “Added to which, I have an aversion to people who talk too much about themselves. Maybe it’s because I’ve always been too sensitive about most people. There’s some sort of chemical reaction. and I just freeze up inside. As a result, I ofttimes give the impression of being detached. It still can’t be helped. Even to those closest to me, I have never been able to ‘open up.’ ”

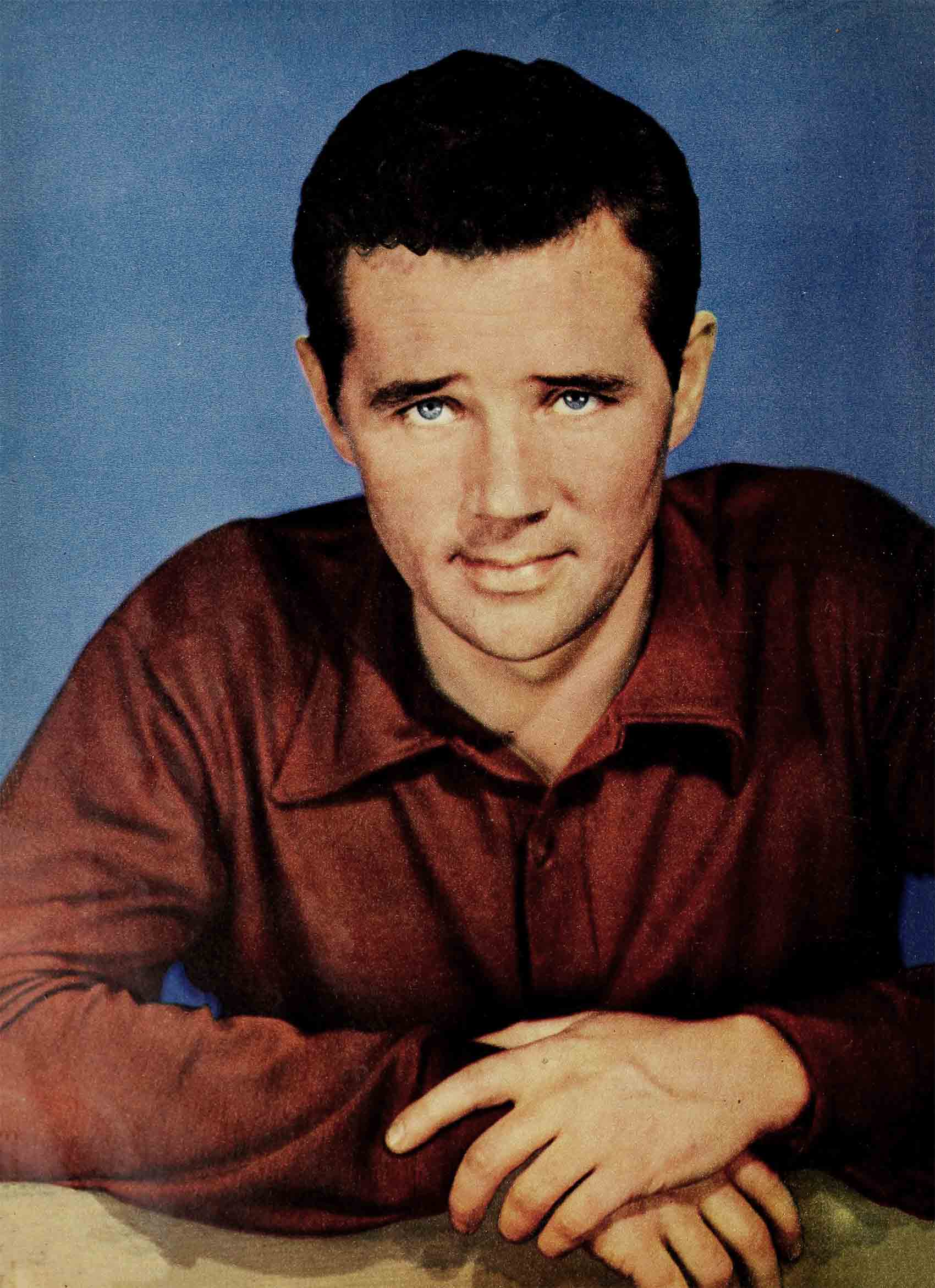

For the benefit of the Spade senders and the Duff devotees, a bit of personal probing proves that hero Howard is six feet tall, weighs 185 lbs. on the badminton court, has brown hair, and blue eyes that can best be described as questioning eyes. For the past two years he’s lived in a small apartment which he still refers to as “temporary quarters.” He eats most of his meals out, hates to cook but admits to being a “helluva egg man at breakfast”—which is usually noon when he’s read most of the night.

To combat loneliness, he likes going to parties where he’s privileged to be a spectator and not a participant. He loves music, old Louis Armstrong records running a fast favorite. With no desire to “compete with James Mason,” he’s crazy about cats. Rumor reports a heartbreaking romance in his enigmatic personal past, supposed religious complications being the cause, but just try and get Howard to talk. “Of course I’d like to be married,” he’ll tell you in no uncertain tones. Gibraltar should live so long, before he’ll be induced to enlarge on that one!

Not too long ago there was Yvonne DeCarlo and the mystery engagement ring that didn’t lead to wedding bells. Hollywood strongly suspects it might have been a publicity stunt. Put the question to him—and Howard lights a cigarette! There was a red head with him one night at Schwabs Drugstore There was a blonde, a brunette, a dinner with Doris Day, which was a publicity “date” for a Beverly Hills restaurant. There was a romance with (and still is, in a manner of speaking)—glamorous Ava Gardner.

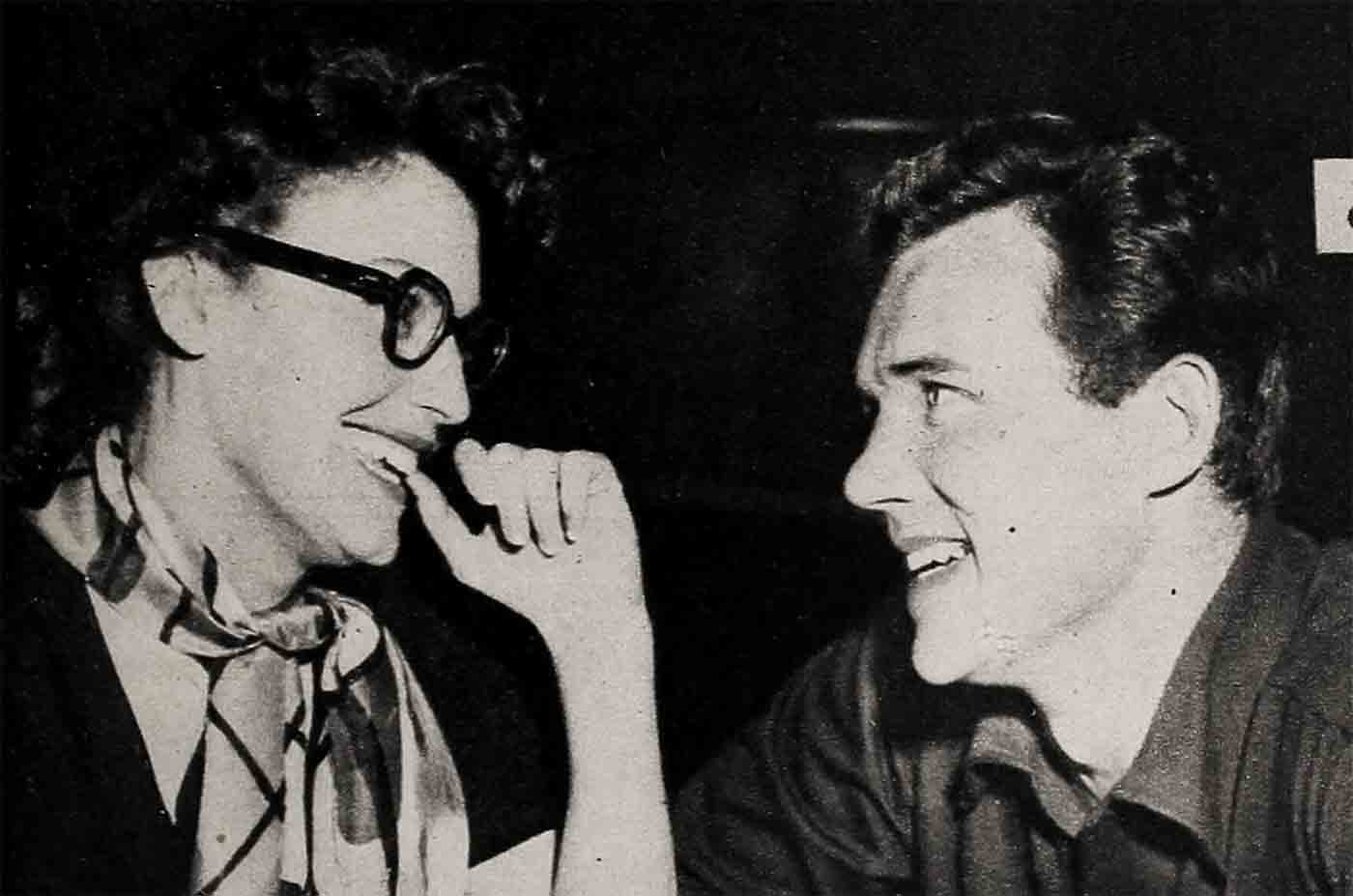

When Ava started “One Touch of Venus,” Howard’s flowers were the first to arrive on the set. A favorite dropping-in place is the “Ready Room” on La Cienega Boulevard, where a corner table is conducive to conversation. There was that moonlit night they “did” every concession on the Ocean Park Pier. One look at Howard’s face when he looks at Ava and you pretty much know what he thinks. Recently a well-known Hollywood columnist tried to get him to elaborate on the subject.

“Ava Gardner’s a terrific girl,” said Howard. And there the interview came to a decisive turning point.

During one period the situation looked serious. Ava wasn’t also dating Robert Walker, Peter Lawford, and the various escorts Howard is sharing her with today. Then something happened. No one knows what and no one is going to find out if they expect either Howard or Ava to enlighten them. They stopped seeing each other altogether. Now they are friends again and it’s a general impression that career, at long last, comes first with Ava. Twice disillusioned in marriage (to Mickey Rooney and Artie Shaw) she obviously has no immediate plans to marry Howard or anyone else.

It was some thirty odd years ago when a son was born to Hazel and Carlton Duff. This was Howard. They were living in Charleston (later changed to Bremerton) Washington. There was a step-brother who was older by ten years. Douglas Duff arrived on the scene when Howard was two. Grandpa Edward Duff (who was mayor for 15 years) practically controlled the town. Because of his various holdings and interests, the boys enjoyed privileges that really set them up with the neighborhood kids. “We were big men in Charleston!” says Howard with that deadpan face, as his eyes gleam with amusement at the memory.

When he was four, his family moved to Seattle. At odd moments Howard showed himself to be a child of hypersensitivity and in strange contrast succeeded in becoming the toughest kid on the block. With brother Douglas as his henchman, he organized “Duffy’s Gang.” They slugged it out with “The Sheiks” (who wore bath towel turbans) in Ravenna Park. In vain did the mothers of his youthful victims despair. It never occurred to anyone that he might be a kid who was fighting against being hurt himself.

Much deeper perhaps than even Howard is aware, are the roots of sensitivity. As he grew up it became all too evident that he had to learn his lessons from life himself. And each was to leave a lasting impression. There was Fran, for example Beautiful redheaded 16-year-old Fran. Howard was 15, and looked much older for his age.

“Every fellow at Roosevelt High wanted to be Fran’s partner at the Tolo Dance, where the girls invite the boys,” Howard reminisces. “I couldn’t even dance, but when Fran selected me, the whole world glowed with excitement and pleasure.”

Alas, the ways of a maid with a man! Her hand in his, Fran lead Howard outside where she produced a bottle of straight alcohol. Nonchalantly taking a deep swig, she held out the bottle to him. Having never tasted anything stronger than near-beer, he manfully, trustingly drank. All hell broke loose in his throat, and years passed before he ever touched liquor again.

During his senior year, playing touch football, Howard fell and broke his foot. So he transferred his interests in athletics to Emma Jergensen’s dramatic class. An oral recitation, which he insists “I did in an Italian dialect with no shame,” won for him the good teacher’s enthusiasm and two roles in the high school production of “Seventh Heaven.” That magnificent escape from reality did the trick. An actor was born.

Howard graduated in 1932 at the peak of the depression: With him into this chaos went the memory of a disillusionment that puts him on the defensive in friendship, even today. His best pal, the friend he admired and trusted, suddenly turned. No amount of urging can persuade Howard to enlarge on the details.

“He was my friend. I believed in him and he told lies about me,” he sums it up crisply. The corners of his mouth tighten. He looks away when he says it.

On rare occasions you get the feeling that Howard does want to talk about a lot of things. You get the feeling, too, that he does want and needs friends. But instinctively he seems to look for a motive -when friendship is offered, undoubtedly because he has been smacked down too often. You feel he’s a romantic sentimentalist. who can never quite forget that reality is forever just around the corner. Just when you feel he is about to open up and talk, up comes that wall.

From 1932 to 1937 Howard worked at anything and everything because he had to work. But he was still serious about acting, and completely incompetent when it came to anything else. Through Emma Jergensen’s recommendation, the Seattle Repertory Theater eventually took him in. A disc jockey job opened up a whole new world in radio. From staff announcer on KOMO, he went on tour with the Washington State Theater. Eventually he landed in San Francisco—broke.

“I never seemed to hit a happy medium,” he recalls. “Either my stomach was full and I had a place to live—or I felt like I didn’t have a stomach at all and I was trying to borrow a buck.”

As staff announcer on San Francisco’s KFRC, his distinctive, resonant voice won for him “The Phantom Pilot.” In Hollywood. where the program had moved, he was on for two and a half years. Eight months before the United States entered the war, Howard was in uniform. He acted, directed, announced, and produced one of the first army radio programs in 1941. After serving at Saipan, Guam, and Iwo Jima, with enough points to his credit he was honorably discharged on November 16, 1945.

Howard returned to Hollywood and radio. In July of 1946, he got Sam Spade (the top mystery program’ according to a recent report) and has been playing him ever since. An excellently acted role at the Actors’ Lab in “Birthday” paved the way to pictures. Jules Dassin, who directed the play, remembered Duff when he was signed by the late Mark Hellinger to direct “Brute Force.” They drew up a contract; Howard signed.

“During the years I’ve been in radio,” Howard sums it up, “what I’m like in person was more or less taken for granted. As a point in proof, some of the listeners who saw me for the first time in “Brute Force” were quite taken aback. Up to that period, so their letters conceded, there existed a sort of general impression of Sam Spade. As nearly as I can make out, they visualized the generous proportions of a Sydney Green-street wearing a Humphrey Bogart face!

“So now here I am in the picture business where it’s part of your job to project your own personality, as well as the character you’ve been hired to portray. In a sense I feel I’m performing two jobs at one time. It’s sort of a challenge, which I am happy to accept. And to be quite honest, I think most actors should learn to be more objective about themselves. Certainly I should.”

Upon completing his recent role in “All My Sons,” with his father now gone, Howard sent for his mother to visit him in Hollywood. The charming, dignified, gray-haired lady thus describes and best explains, perhaps, her devoted son:

“Howard never did have a great deal to say. He preferred to read and remain in the world of his own imagination. I think his worst fault is either violently liking something—or violently disliking it. There is no happy medium. However, when he accepts a responsibility, anything he does he always does with all his might. It’s his way of saying, this is everything I have to offer—the best I have to give.”

For Howard Duff especially this story is written—in the hope that some of the things that should be said, havebeen said. Things he could never say for himself.

THE END

—BY JERRY ASHER

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE JULY 1948