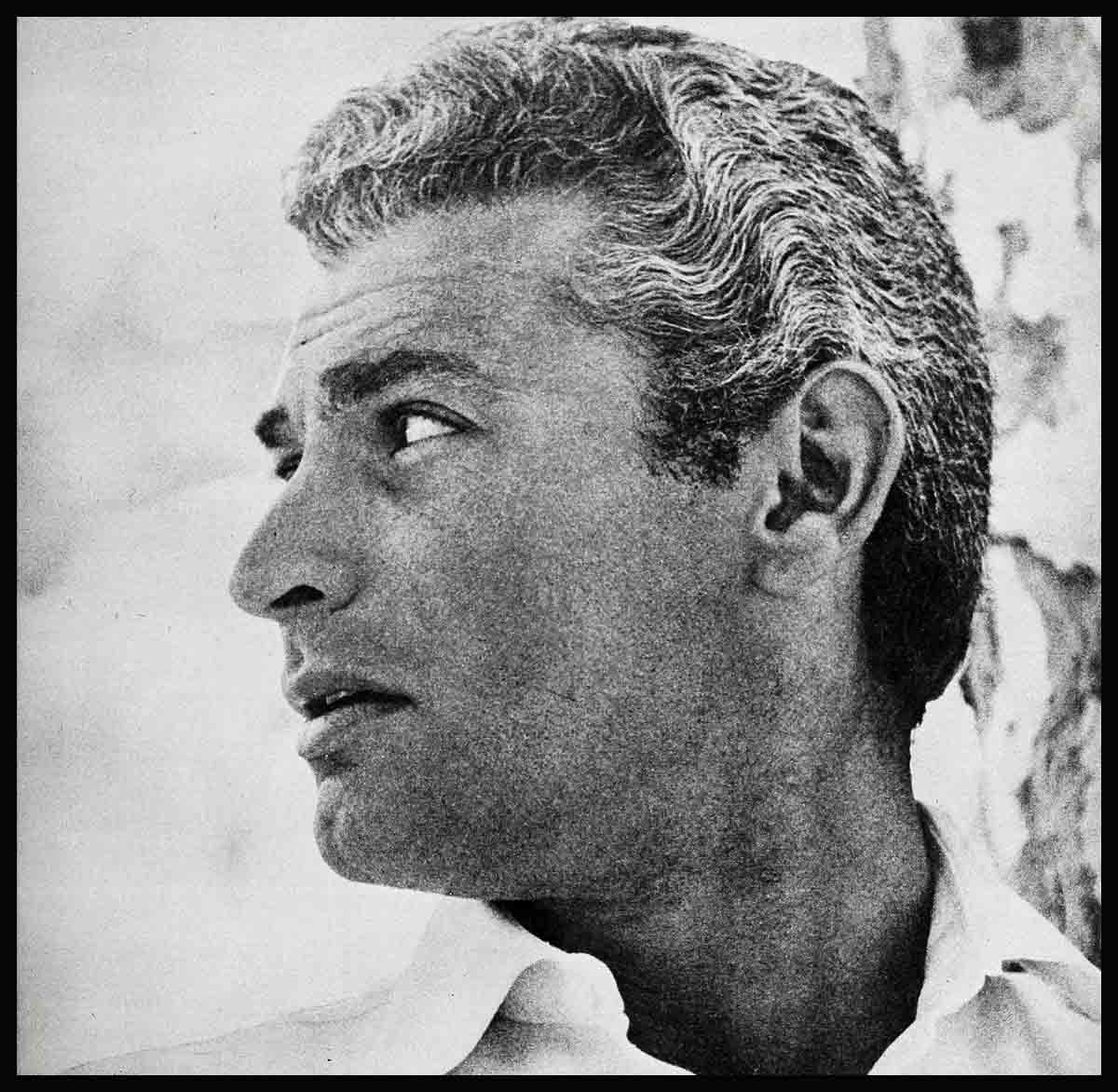

His Lady Carries A Torch—Jeff Chandler

Together, the excited six-year-old in the sailor suit and his dark-eyed immigrant mother were climbing the Statue of Liberty. This was the Lady his grandfather talked about. The Lady he showed him from their apartment in Flatbush. The Lady of Liberty. . . .

Together they circled and circled. Up the stairs as high as the Lady’s waist. They were too dizzy to go on. But young Ira and his mother wanted to go on higher. They tried again, and slowly, step by step, they made it to the top.

“I went all the way,” young Ira told his grandfather proudly, when they got home. “Clear to the top of her head.” She was no statue to him. She was real and living—the Lady of Liberty. She was the reason his grandfather had brought Ira’s mother and the rest of his brood from Vilna, Russia, to this new Promised Land. The reason, he told them, that he, Ira Grossell, could be whatever he wanted to be when he grew up. And climb as far and as high as he would.

Today Jeff Chandler’s still climbing. He’s making history, one way or another, in Hollywood. Primarily, he would tell you humorously, as “the youngest Civil War Veteran.” And impartially so—having fought in the films—and repeatedly—on both sides. As he is fighting again in “Brady’s Bunch,” a post-Civil War picture, at Universal-International now. In addition, he’s Hollywood’s most famous Native American of all time and all tribes. “You are Cochise,” Elliott Arnold, author of “Blood Brother,” wrote on the book’s flyleaf for him. The words have proved as prophetic as they were complimentary. Yet the producers of “Broken Arrow” once studied him quizzically. They were having a little trouble, they said, trying to visualize him—a typical All-American—as an Indian. “But what,” he asked them, “could be more typically American than an Indian?” He, of all people, should have known. The grandson of an immigrant—Jeff Chandler.

Jeff’s family came over on a crowded boat teeming with a medley of accents. There were his grandmother, Sarah Shapiro, his mother, Anna, uncles, aunts. His grandfather, Max Shapiro, had come a little earlier to make a place for them. He set himself up in a little butcher shop in Brooklyn, and he found and furnished an apartment and proudly had it all ready and waiting. In it were the most advanced wonders he could afford in the new land—steam heat, a coal range, a sewing machine. “Mama, a machine that sews all by itself.”

And for young Ira there was the gift of being born here—of growing up within the warmth of the Lady’s torch.

From the age of three, when his parents separated, Ira and his mother lived with his grandparents, and he grew up under the guidance of the wise old man.

His grandfather hoped that some day young Ira would want to be a Rabbi. But from childhood on, Ira had his own ideas. He would be an actor, he said. As his mother, Mrs. Anna Shevelew, laughs now, “When he was four years old—Ira would parade around with a hot water bottle in his belt, a broom over his shoulder, and carrying a can opener—and inform us he was being a ‘hobo.’ ” He was always doing imitations too, mostly of Groucho Marx. He had an ear for music, and before long his mother was taking him to see Broadway shows—then wondering how to get her happy but sleeping “star” off the subway and home again.

Even then, his were determined dreams. Every Saturday his mother gave him a nickel to pay his way to the movies—this seven-year-old’s biggest thrill. One Saturday when his mother got home from work, she was surprised to find young Ira waiting on the steps for her. “Didn’t you go to the movies?” she asked.

“No—I had something more important to do with my nickel today,” he said.

“More important? But what?”

“Go upstairs and you’ll find out,” he instructed soberly.

There she found one red carnation, and with it, lovingly scribbled for the morrow, “To my Mother on Mother’s Day—and this ain’t nothin’ yet.”

His first set-back occurred when he lost his chance at a big part in the grammar-school musical because his voice was changing. “I could sing the high part and the low part—but I couldn’t manage the middle,” Jeff says, with a wince even now at the memory. “I wound up Stage managing instead,” he grins.

Nor was he discouraged even when, as an eager teenager, he lost out in the local try-outs for Jesse Lasky’s CBS talent show, “Gateway to Hollywood.” “I was broken-hearted that night. And right then and there I swore—” Jeff laughs, giving it the full melodramatic treatment. Then he adds slowly, “but it took me a long time to get here.” Remembering just how long. . . .

Too long, as life—and death—willed it, for his grandfather to share in the happy day. He was bed-fast with cancer when Ira was thirteen, but he did have the happiness of hearing his grandson deliver a speech as moving as any he would ever make later on the screen—an emotional tribute following his confirmation. The Synagogue was next door to their apartment, and the earnest boy in the new dark suit knew that through the open window his grandfather could hear every word. And every word was from Ira’s heart.

On this day of manhood, he wanted to acknowledge how much his mother’s and all his family’s love and kindness meant to him. He wanted to thank his grandfather for all the good things he’d taught him, and for his own future—because of all of them. The proud old man listening felt a great sense of peace. He was a good boy, Ira. He would be all right. He would do fine. Go far.

Today Jeff’s fulfilling an immigrant-American’s faith in him. And all the reasons why are reflected in his face and physique. In the feeling he inspires of solid inner strength. In his humor towards himself and his grave awareness of all others.

Jeff believes that size is a big help in Hollywood. “That first entrance coming through the door is challenging. I frightened people into giving me jobs. A big guy walking in makes ’em look up. This happened to me in radio, too. The man behind the desk is startled into thinking, ‘Say, if this guy can act, he might be pretty good.’ ”

Virility and height are important. But Jeff’s bigness, those who know him well can tell you, is measured in terms of tolerance and thoughtfulness and understanding. If there’s no housekeeper and Marge, his wife, has to do all the work—he worries. If his agent, Meyer Mishkin, has the flu—Jeff’s on the phone to his house at least twice a day. When Martin and Lewis do a television show, the first congratulatory wire they get is Jeff’s. Often, when he’s away on location, he calls friends long distance saying, “I just wanted to hear what’s new—tell you I miss you.”

He’s also concerned about his fans. Jeff’s probably the only star who, on a day off, spends the time from 10:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. dictating warm personal notes to fans, answering their questions and advising and encouraging them. To a girl in West Virginia who asks about becoming an actress, he gives the names of various drama schools and their prices and says, “It’s a wonderful ambition, Marie. May all your dreams come true.” He rejoices with a boy who’s been stricken with paralysis over any new feeling of movement that returns. “ . . . your last letter was exciting! What joyous news—that the feeling’s come back in your wrist again. Thanks for writing me about it and making me part of your happiness . . .”

It was Jeff’s thoughtfulness that won Marge’s attention when they first met in New York. “I was just visiting there. I’d been ill and I was feeling a little lonely, and Jeff was so protective and kind. I was a little overwhelmed. We talked about the theatre and I just mentioned something about once going completely blank on the stage and forgetting my lines—right in the middle of ‘The Swan.’ Two days later a pair of little swan-shaped earrings arrived. It was so personal and so very thoughtful—I was quite impressed. But that’s Jeff,” says Marge, “now I know . . .”

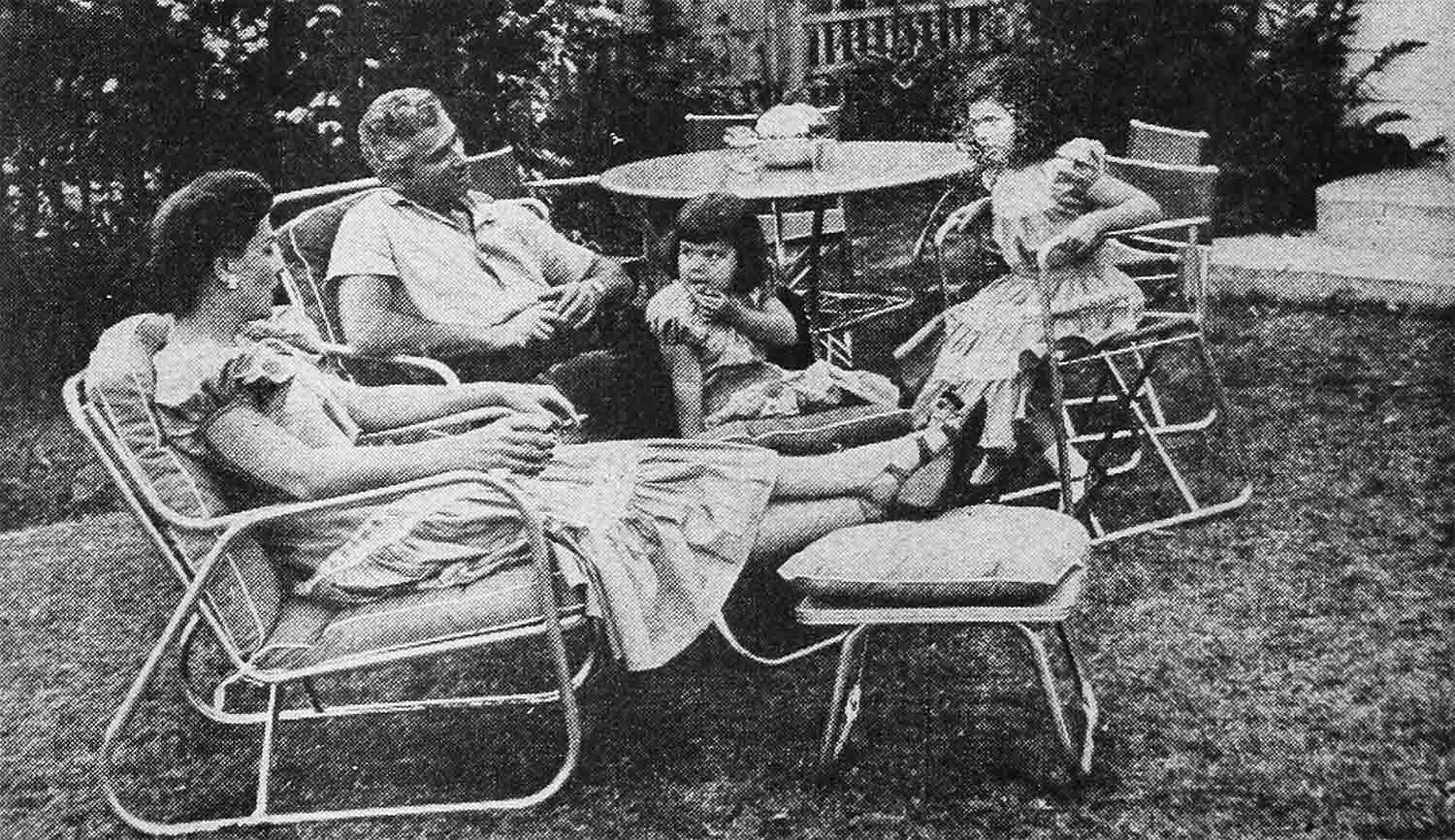

Now, of course, as Jeff would be the first to point out humorously, she knows many other things about him too. That at home he’s a casual relaxed kind of character who prefers to remain that way—casual and relaxed and at home. That, although he’s always going to take her to catch the headliner at the Mocambo or Ciro’s, somehow they never get there. That since Marge is feverishly taking tennis lessons he’s going to go out to the court on Sunday and work out with her—but they never make it. As she says, “Jeff’s a spectator sportsman.” He loves to watch—preferably while stretched out in the sun in his own backyard with his own daughters, six-year-old Jamie and three-year-old Dana, busily at play nearby. He plays a great game of baseball, loves to bat the ball and reach up and mitt a wild one—as long as somebody else does the running for him. “I’m the artistic type,” he explains lazily.

Marge knows now, too, that her husband’s a dream man about admiring a smart new suit or her latest hair-do. That in the food department, he likes his beets cold instead of hot and canned peas, instead of fresh. That he has an aversion to gushy people, and that if he’s cornered at a party and Marge doesn’t happen to catch his restless unhappy look and move in for the rescue, she’ll be greeted later with “Where were you?”

“Marge knows me pretty well. That’s the price she has to pay for living with me,” he says. But in all fairness to himself, and contrary to any rumors in the past, Jeff is quick to say he’s never raised any objections to a wife having a career. “I’ve never minded Marge’s working. On the contrary I’ve encouraged it.” As he points out, he’s hardly a man who would deny women the rights and freedoms they’ve fought for. “She just finished the second lead in ‘Dangerous Crossing’ with Jeanne Crain and Michael Rennie, at Twentieth Century-Fox. I like Marge to work—if only so she can appreciate how hard I work,” he grins.

Jeff is a very thoughtful and affectionate parent—and his daughters’ ever-willing audience when they put on their “shows”. He totes in the chairs for himself and Marge, and helps with the sound effects while Marge brings them “on” at the piano. Using the fireplace as a stage background, Jamie announces, “I’m going to do a ballet.” Then Dana follows, imitating Jamie doing a ballet. They do duets together too on the Roy Rogers theme song, “Happy Trails to You.” And their proud parent says, “Amazingly enough, sometimes they sound real good.” He would be the last to deny them self-expression even if they didn’t. The memory of a little boy who “hoboed” for another appreciative audience in a Flatbush living room is very vivid.

But play-acting is only a small phase of the children’s lives. Both their parents are concerned with their religious understanding. “They must know all religions,” Jeff and Marge agree and they take them to churches of various beliefs. And every Sunday Jeff reads a few pages of the Bible aloud to them.

Jeff feels a quiet deep anger at intolerance or injustice of any kind. Today he’s still searching for his own answers, and he won’t be hurried into accepting a substitute. He is, as Jerry Lewis says, “the most honest guy you’ll ever know.” And beneath the Hollywood war paint he’s one of the most sentimental too.

But he also has a dead-pan humor which can relieve any situation and often, he would say, at the wrong time. He turns a phrase well—and usually at his own expense.

These days, Jeff is worrying less and laughing more. And suffering less too at his own previews. When a picture’s sneaked, he and his agent, Meyer Mishkin, have always arranged to get away from the crowd and meet later for coffee and comment. By now, they have a routine. They shake hands gravely. Then, “Well, what do you think?” asks Meyer. “Well, it’ll make money,” says Jeff.

But money-maker that Jeff is, he’s still having trouble convincing Hollywood that he can play comedy or do musicals—even with his agent insisting that when Chandler croons, it will be as earth-shaking as when Garbo talked. So sincerely does Jeff project himself into a part, that producers have difficulty ever visualizing him in any other. Ever since the first time he played Cochise, he’s been trying to get his clothes back on. But to his agent’s, “He’d be great in drawing room comedy,” producers would shake their heads. They just couldn’t see him that way. So strong was this feeling, that throughout the first rushes of “Because of You,” Jeff, surrounded by executives admiring him in his elegant modern clothes, kept asking anxiously, “How do I look? How do I look?”

Getting this picture, Jeff says, was an “Also,” he adds simply, “Loretta Young was lighting candles for me.” The part was actually already cast, when Jeff met Director Joe Pevney in the street at U-I one day and heard him talking enthusiastically about the script. “Anything for me?” asked Jeff.

“Too bad the lead’s already cast,” the director said. “You’d be so good in it. You probably wouldn’t want it though. It’s a smaller part than the woman’s.” A smaller part than Loretta Young’s? Who cared? Just give him a crack at it.

“Do you mean that? If we can fix it, will you do it? You won’t back out?” At first the studio didn’t want him to do the role. As Jeff says, a little embarrassed at just how to put it, “They didn’t think the part was . . . big enough. But I waited it out while Loretta would light another candle. . . .”

This emotional role is Jeff’s favorite to date—and, strangely enough, the one he found easiest to play. He grins at the incongruity of the picture, as he says, “The physical stuff is really hard for me. The fighting, the running, the jumping on horses, or climbing a cliff. I have a fear of height, anyway. I get dizzy . . .”

But height in Hollywood—no matter how high Jeff goes, or how long he remains there—couldn’t dizzy his own sense of values nor inflate them. A student of underacting, his greatest underplaying is of himself. And sincerely so. “The gimmick in motion pictures is to have a personality that projects. There are fine actors who aren’t working. But if you’ve got a personality that projects—you’re in. You can’t take too much cerdit for that. It’s something you’re born with.”

He’s a fan of many other stars. As he puts it, “It was like taking lessons for me—just watching Loretta Young work.” And today Jeff and his agent, his fighting ally since the night they met backstage when Jeff was playing a supporting role on Lux Radio Theatre, keep passing the buck back and forth between them. When he’s swamped by fans clamoring for autographs, his agent says, “Big movie star,” kidding him. “You did it,” says Jeff. “You helped,” Meyer reminds.

Theirs is a rare loyalty, as big agencies who’ve tried to buy Jeff away have found. And of Chandler, Mishkin says, “He has virility, vitality, a tremendous dignity. All this, and he can act too.” He’s been sold on Jeff since he saw him in a play when Jeff was going to Feagin’s Dramatic School in New York. Mishkin, then a talent scout for Twentieth Century-Fox, says “I was impressed by this tall gawky young kid and his wonderful voice, but at that time the studio was looking for pretty boys—and he didn’t fit the picture.”

Years later when they met at the radio rehearsal, Mishkin recognized him. “I know you—but as Ira Grossell,” he said. Jeff couldn’t get over it. “But that was years ago! Why would you remember me?” That night Jeff went home and told Marge—“I’ve finally found the guy I think I’ll go places with.” And Meyer told his wife, “I met a guy named Jeff Chandler today. I believe he’ll be a big star. . . .”

At present, they’re crusading to convince Hollywood that Jeff can sing. Jeff, who describes himself as an “Eastern-style singer . . . no guitar,” admits he’d love to do a musical—“and there’s some talk about it . . . mostly on my part.” However he does have a “handshake agreement” with Sonny Burke of Decca Records to make a record for them “ ‘some day when we have time.’ Me? I’ve got all the time in the world. They’re busy.”

Whether in Flatbush or filmland, Jeff’s as down-to-earth as a guy can be. He lives in an unpretentious white Colonial house, with an enclosed yard for the children’s play and a last year’s convertible in the driveway. Like others who rent, the Chandlers keep drawing up blueprints for the dream home they plan to build. They have a lot—in the Sherman Woods section of the San Fernando Valley.

“We go out and look at our lot longingly, and we walk up and down, pacing it off. Ours is the only vacant gap in the midst of all the homes and lawns and flower gardens there. And I can see the neighbors watching from their windows and wondering, ‘Isn’t this guy ever going to build?’ Movie star that I am,” he grins.

Not that he would be anything else, out of choice. Acting is his life and his legacy. “I can’t think of myself as anything but an actor. This is what I always meant to be. Hollywood is where I always meant to be . . .

“Today is a lot of dreams come true,” Jeff says slowly.

Not only his dream, but those of others very dear to him. Including a devoted elderly immigrant, who didn’t live to see it—but who died full of faith that in his grandson, Jeff, his own dreams of ail that America means would be fulfilled.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1953

No Comments