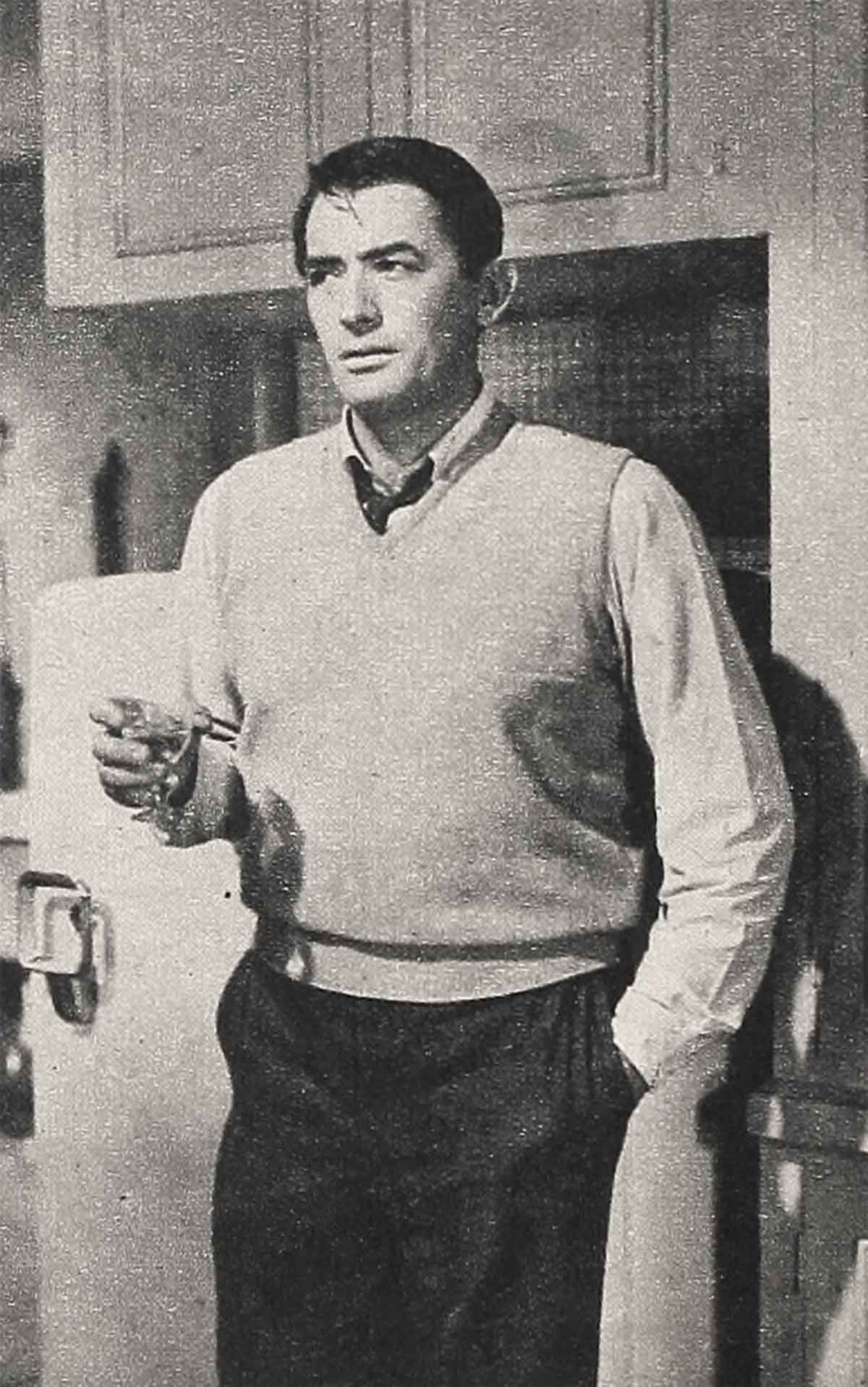

Why Gregory Peck Walked Out On MM?

If they had paid attention in September, they might not have been so stunned in November. It wasn’t that the glamourous Marilyn Monroe hadn’t served notice. For way back in September when it was considered too risky to let Khrushchev see Disneyland but safe to let the Soviet boss watch Frank Sinatra and Shirley MacLaine cavort at 20th Century-Fox in a scene from “Can Can”, Marilyn had sent up her first disregarded warning flare.

The trouble was that everyone was paying too much attention to Nikita’s visit and too little attention to Marilyn’s visit. If they had kept their eye on Marilyn instead of Nikita during the luncheon honoring the Russian head of state, it might not have come as such a shock.

While Nikita found himself unable, at least in retrospect, to abide the sight of a galaxy of smiling Can Can girls with their motors running, Marilyn was quietly racking up some behind scenes mileage of her own.

She had agreed to co-star with Gregory Peck in “Let’s Make Love”, and during the Khrushchev visit, she went into a cozy huddle with her personally approved director, George Cukor, studio head Buddy Adler, producer Jerry Wald, and Norman Krasna, author of her farewell picture as a reluctant 20th Century contractee. One of the crucial things she got across in that meeting with the film factory brass hats was that she felt her part needed some building up. It was a neat piece of summitry.

Right then and there, if Hollywood oracles weren’t operating with rusty geiger counters, they would have picked up the sound of approaching turbulence. Everyone was so busy finding out what Nikita thought of everything, however, that they neglected to ask what Gregory Peck thought of Marilyn’s impending build-up.

Even before Marilyn more or less upstaged herself out of a leading man, studio. insiders on the sub-summitry level were steeled for a full-scale ulcer fallout.

“We used to wonder,” one studio veteran confided, “if they’d ever finish the picture. It never occurred to us that they might not start it.”

This foreboding stemmed from an awareness of fundamentally differing attitudes that Greg and Marilyn had cultivated toward their art.

“Peck’s very precise,” it was pointed out. “He comes on time. He’s serious about his work, and expects others to be just as serious. Marilyn, of course, may take it into her head halfway in the picture not to show up. It’s always possible with her that she may not turn up on any given date.”

“Greg worries a lot,” my informant observed. “He has changed a good deal, and so has Marilyn, as everyone knows. Peck now rehearses a lot. He doesn’t want anyone on the set seeing him rehearse. He didn’t used to be that way.” Marilyn, of course, has been that way for quite a while. She is famous for her attacks of jitters while a picture is in production. It was a fear of two touchy people too much involved with their own phobias. The fear, in short, was that a time bomb was ticking away and that it would likely go off somewhere around mid-picture. There was no suspicion that actually it was a pineapple with a short fuse, and that it already was burning merrily toward the point of detonation.

When Marilyn reported for work, she was well fortified. One flank was protected by her drama coach, Paula Strasberg. The other was grimly walled off by her husband, playwright Arthur Miller, who would seem as compulsively caught up with Marilyn’s welfare as with the woes of the world.

Arthur and Marilyn took one look at the working script—the blue script as they call it at the studio—and hastily confirmed Marilyn’s earlier diagnosis. Her part, if not her anatomy, needed firming up. Miller put his Pulitzer prize hand to it, and the happier Marilyn got with the revisions, strangely enough, the gloomier Peck got.

Not that Peck, who is justly known for his magnanimity, wasn’t magnanimous in the beginning. He conceded that Marilyn’s part, in the original script, could stand some enlargement without damage to his prestige. And this despite the fact that he, not Marilyn, had script approval.

However, even when the please-Marilyn campaign seemed to him to get out of hand. Peck was not one to make a scene. His announced reason for bolting was that the delayed start in shooting—delayed, incidentally, by pro-Marilyn changes in the script—would extend the agreed upon stop-date by one week. Under these circumstances. Greg maintained, as if nothing else was bugging him, he could not finish in time to meet his next commitment, “The Guns Of Navarone”, which is to be filmed in Greece.

Peck admittedly was on firm contractual ground, but there was little doubt that an accommodation of conflicting dates might have been worked out if Greg cared to go ahead. It was just about the time the picture’s title was changed to “Let’s Make Love”. Peck’s tart rejoinder was, “Let’s not.” No one familiar with the backstage pouting was naive enough to question what really triggered his exit.

Promptly thereafter Hollywood repaired to its joyous post mortem sport of choosing up sides. Oddly enough, Marilyn found more support than might have been expected within the palace walls—a palace whose offerings she has repeatedly spurned and whose nourishing paternal hand has felt the bite of her ungrateful teeth more than once.

“Arthur Miller did work on some scenes,” I was informed by an objective studio source. “The studio felt they were not serious changes. Peck felt they were, so he bowed out.”

The consensus of opinion among disinterested studio observers who had seen the script revisions was that they did not substantially alter the picture or downgrade Peck’s part. This inescapably left the door open to the suggestion that Greg may have felt, since he did have script approval, that he should have been consulted and/or that being only human he resented being taken for granted while Marilyn was being fawned over.

There was nothing to support a case of personal feuding or fussing. The one time Greg and Marilyn met was during a dance rehearsal, and they were entirely cordial. Even if they eventually might have gotten on each other’s nerves, they didn’t have the opportunity.

As far as the public is concerned Marilyn is more crisis prone than the seemingly imperturbable Peck. Her sword crossing with Sir Laurence Olivier during the shooting of “The Prince And The Showgirl” was an internationally reported sample of what might be expected from the new and more assertive, but apparently still insecure, Marilyn. There were rum blings of script concessions to Marilyn on “The Prince And The Showgirl” and she didn’t exactly get the short end of the writer’s stick on “Some Like It Hot”.

Marilyn, lovable and cuddly as she is can be a problem.

It is true that fundamentally Peck is as reliable as ever. In many respects, he doesn’t seem to have an erratic bone in his Lincolnesque body. But what is not generally known is that Greg has been growing more demanding in the practice of his trade—albeit not unpleasant.

It was he who insisted on making the script revision in “Beloved Infidel” with Deborah Kerr. He had no qualms what ever over bending the image of the late F. Scott Fitzgerald to the convenience his own personality and acting range.

“No sir,” the man at 20th nodded, “this isn’t anything brand new with Peck. He made an awful lot of changes on ‘Beloved Infidel’, and he’s been persnickety about his scripts for some time. In fact, it’s been the talk of the industry in recent years. He and Willie Wyler had a helluva thing on ‘Big Country’. Apparently, he has the impression he knows what he wants to do in pictures. I guess as long as he can make it stick, why shouldn’t he’s. Of course, Marilyn’s a bit of a pip, too.”

Whatever the merits of the tempest there was no shortage of volunteers to fill in for Peck. The prospect of playing opposite Marilyn, even as watered down co-stars, did not seem to discourage some of Hollywood’s most glittering males from offering themselves as replacements.

Within 24 hours, a dazzling list on possibilities was being publicly considered among them Cary Grant, Charlton Heston, David Niven and Rock Hudson. If any were insulted at the suggestion of handling Peck’s rejected skirmish with Marilyn they neglected to tell their press agents. As this was written, Rock Hudson was being most ardently wooed, and reportedly was so eager to take his chances with a Marilyn-oriented script that he was begging his studio to okay a loanout.

Meanwhile, once out of it, Peck did his best to maintain a cheerful aloofness. He was even philosophical about the arduous dance rehearsals that had come to naught.

“At least,” he grinned, “I learned to do the buck and wing, the double wing, a time step, off to Buffalo and the fly away.”

And considering private estimations on his displeasure, he executed the fly away very gracefully, indeed.

THE END

—BY MARK DAYTON

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MARCH 1960