Ted And The Amateurs—Ted Mack

Ted Mack’s “Original Amateur Hour” is now 1,001 broadcasts old . . . as of April 10. . . .

The equivalent, in human terms, of a spry oldster’s 4,000th birthday—on the basis of TV contracts calling for thirteen weeks, and renewable if all’s well.

And all is well with Ted and the eager amateurs displayed over 115 NBC-TV stations, Saturday evenings at 8:30. EDT. “There are just as many talented amateurs today,” says Ted, “as there were twenty years ago.”

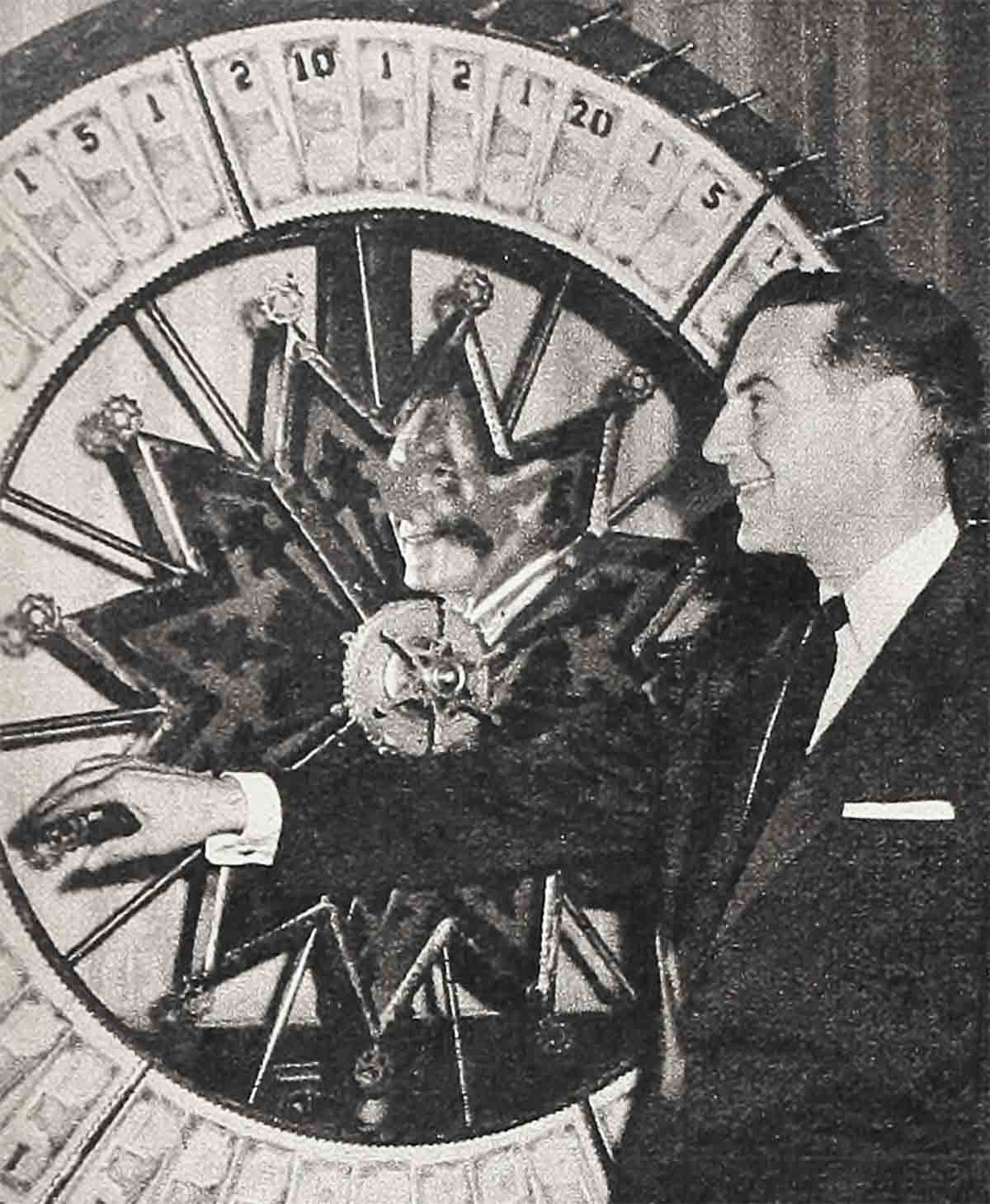

It was twenty years ago when the late Major Edward Bowes took to radio with the program and his: “The Wheel of Fortune spins. Around, around she goes, and where she stops, nobody knows. . . .”

The wheel stopped on the winning jackpot number for the program itself—Bowes units swarmed over the entire U.S. after the show became a top radio favorite. After the major’s death, Ted Mack, his right-hand man, took over, and the show went on television.

Eight hundred thousand hopefuls have been auditioned by both regimes. Of the fifteen thousand who reached the air, some have fallen by the theatrical wayside, many have done well or fairly-well—a select few made the very top, such as: Frank Sinatra, Robert Merrill, Mimi Benzell, Vera-Ellen, Regina, Resnick, Stanley Clements, Jack Carter, Teresa Brewer, Frank Fontaine, Ray Malone, Larry Storch, Paul Winchell, Dave Barry, et al. Some of the old grads showed up for broadcast No. 1,001.

Three-time winners on the half-hour “Hour” compete on June 19 at the show’s Annual Championship finals at Madison Square Garden—the highlights to be televised. Cash scholarships run up to $2,000 for the top money.

Pet Milk, the sponsors, reports that the amateur show is their best salesman, with Mr. Mack the idol of their customers. Which suggests something—everyone knows the amateur story, but how many viewers are up on the life and times of Ted Mack? Is that his real name?

Ted Mack was born William Edward Maguiness, February 12, 1904, in Greely, Colorado. The family moved to Denver, where Ted graduated from Sacred Heart High, worked as a theatre usher, fell for the saxophone playing of the Six Brown Brothers (remember, Dad?)—then had to do his saxophone practising in a closet because his father, a railroad brakeman, worked nights and slept days.

For economic reasons, Ted became a Denver stockyard hog caller during summer vacation from law studies at Denver University. He understandably jumped at an offer from a cowboy orchestra—a hot bath, and he was ready, saxophone in hand. Since Ted was the only member of the band who’d been within four feet of a cayuse, he was also the only untroubled musician—aside from the bass player who stood up anyway—after a press agent had decided that the band should parade to the theatre in San Francisco on their fiery steeds.

Ted’s orchestral career—out of the saddle—included work with Ben Pollock, alongside many musical greats-to-be. In 1926, after he heard that a rival was beating his time with his childhood sweetheart, Ellen Marguerite Overholt, Ted dropped everything to go back home and marry the girl. Together, they organized a band—Marguerite, its manager and Ted’s chauffeur—and they began twenty years of failure and success. There are few more strenuous tests for a marriage than this.

The balance of the Mack career has been too well publicized to need further repetition—how he become the first assistant to Major Bowes and, later, his successor.

Ted is unquestionably the logical Bowes replacement, but no one in this wide world was ever more unlike the pontifical major than is Ted. The major was the big-business tycoon personified—pince-nez, high stiff collar, very conservative clothes. He maintained a minimum of one hundred suits, was always shaved in a barber’s chair installed in his luxurious apartment over the Capitol Theatre, in New York. His chiropractor and tailor both obligingly moved nearby—the latter obviously couldn’t stay away from the major very long, anyway. Major Bowes could have passed for the President of U. S. Steel—was probably much richer. . . .

Ted, on the other hand, is a quiet fellow who wouldn’t be noticeable in a crowd. Slim, dark-haired, long-nosed, he’s better looking off TV than on. He only has four suits, but he has a lot of old Levis that smell of the stable. His barber’s chair is in the local haircutting emporium.

His associates say he’s genuinely kind, and has an even disposition, but if he’s unfairly-treated, he can respond with vim and vehemence—no sissy-pants, he. “Ted has a charming sense of humor,” says one of his staff. “He’s an expert with the really subtle gag—he’s been a professional emcee for years, of course, so he’s always able to handle any program emergency. His jokes, by the way, make Mack the butt, not other people.”

His sponsor, the Pet Milk Company, is probably Ted’s biggest fan, and recently devoted the lead article (and cover) of the company magazine to Mack & Co.

Visitors from all over the world turn up at Ted’s office, because he told them to look him up when they came to New York, and he’s that one-in-a-thousand who means such things when he says them. Affable, warm, sincere, and unaffectedly-natural were adjectives applied to Ted by the publication, and they offered a parting salute to his be-yourself advice to amateurs, which they felt he also took as a personal guiding principle. The Mack brand of the milk of human kindness is obviously acceptable for processing by the Pet Milk Co.

Ted and Marguerite own their own home. This is a significant thing, since it’s the first they’ve ever had, and it’s located in Irvington-On-Hudson, N. Y., near the Sleepy Hollow of Washington Irving fame. It’s a small place—five rooms, nothing grand, no barber’s chair— complete with dog, who if he has a pedigree, has never thought to mention it. He’s the dog who came to dinner, then adopted them.

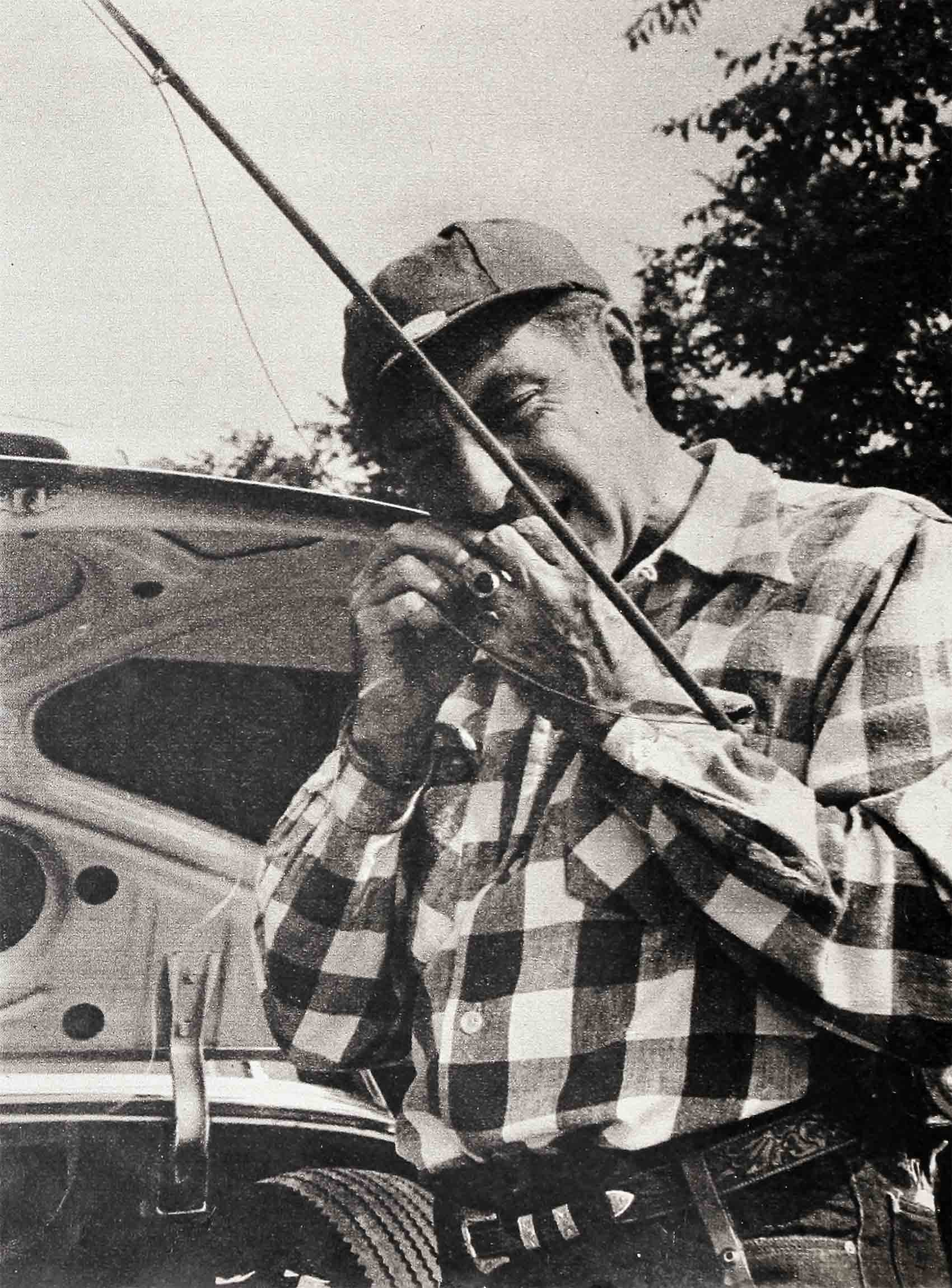

“Some day,” says Ted, fervently, “I’m going to own a farm. It’ll be heaven. . . .” Can you imagine the major languishing for love of a farm? So far, Ted has bought 50 head of Herefords (cows). They’re boarding with a Virginia crony who has made the grade, in the rural sense. These cows were bought in small lots at sales all over the country, whenever the Irvington hayseed was making personal appearances with performing “Amateur” winners. The magazine rack is loaded with farm and cow journals, which give Ted a faraway look—is Queenie contented in Virginia?—when he digs into them.

Ted has a desperate need for a farm with a gigantic red barn—to hold the gifts he receives. “We ran out of space years ago, at home,” he says. What, no room for the world’s largest raisin pie? Or the pretzel that weighed forty-five pounds? An Honor City’s state forwarded the longest long-horn steer, but when another state, whose flag bears a lone star, heard about it, an even longer longest-long-horn-beast showed up.

“I get an enormous kick out of the good-will represented by these kindnesses,” Ted swears.

In his office, Ted keeps a gift model of the first Lackawanna locomotive, a ditto of a famed Lake Champlain steamboat, fire and police hats, topped off by a diamond-and-ruby-studded can opener. There are thousands of handkerchiefs from admiring ladies.

This has ever been a show that attracted big names, as well as talented kids panting for a break. When Major Bowes suffered his final illness, no less than Archbishop (now Cardinal) Spellman conducted the program in his stead. The “Amateur Hour’s” VIP charity shows, out of Washington, feature the Cabinet, Senators, Representatives, and Army brass, all playing brass and woodwinds, singing, or tripping the very fantastic. Celebrities a la Ed Sullivan, Max Baer, Earl Wilson, Perle Mesta—name them, they’ve been here—decorate the program or occasion, and are tickled to be asked.

Such big-name didoes might well turn the head of a smaller man, one with less common sense. But Ted’s head always turns to his little gray home in the Westchester sector. . . .

THE END

—BY WILLIAM LYNCH VALLEE

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE JULY 1954