Happiness Is A State Of Mind—Jean Simmons

Jean Simmons had invited me to her home many times, but I hadn’t managed to get there until the morning of our interview. When she phoned, just as I was putting on my new hat, to suggest she’d meet me at a given point and lead the way, I was skeptical of the need for such service, but by the time I spotted her little putty-colored Jaguar waiting at one of the hairpin curves of the highway, I was eager to encounter my guide.

I began driving behind her, and suddenly her roadster plunged through a gap in the shrubbery and onto a curving lane which wound sharply around the mountain until we were climbing almost straight up. Speeding through a breezeway, we came out on a huge, circular brick-paved court with a swimming pool. The low gray house circled three sides of the landing spot like a protecting arm. Below us lay the world, stretching off to an infinity of sea and mountains on every side.

“How did you find this eagle’s nest?” I asked. “I didn’t even know it was here.” .

AUDIO BOOK

“We used to go prowling around, and one day we came on it,” Jean said. “It wasn’t finished—there was nothing, really—not a tree or a plant or a blade of grass. We completed the building of the house and Jimmie brought up every single thing, even that birch tree over the kitchen roof. He planted the hill all the way down to the main road—about an acre in all.”

“An acre of heaven,” I murmured as we went inside. I had come to do a piece on Jean and happiness. When I peeped into the dictionary to see what happiness included, I found such incidentals mentioned as: pleasure, success, prosperity, luck, living in concord.

I was out to learn whether a little girl born of a poor family in Golder’s Green, London, twenty-five years ago, had acquired this state of mind along with fame and life with the man of her choice. If you expect the conventional picture of a young girl’s dream of married bliss, then the Jean Simmons-Stewart Granger marriage is an upside-down cake. The traditional rose-covered cottage is missing, but what they have, they like better. There are no children running around the door, but there have been, and will be again. And you’ll never find Jean Simmons with an apron, elbow-deep in soap suds—trance-deep in a book is the way she likes to be. For this marriage follows none of the established patterns. But then Jean is not the average young girl; her very adult mind draws her to mature people rather than to those her own age. For her, happiness would truly be a state of mind—completely different from anyone else’s, or am I right?

Jean’s “cottage” has a great main room with one entire wall of glass, and we paused before it to catch an eagle-eye view of mountains and ravines that fell steeply away from our feet. (The house is perched at the brim of the sheer cliff.) The room itself is an interesting mixture of sport and and the arts, a schizophrenic combination of big-time trophies, fine canvasses, Ming porcelains, Tang horses (the most magnificent specimens I’ve ever seen), Rodin and Jacob Epstein sculptures and Chinese stone figures of great antiquity. It might make a decorator wince, but the whole is stunning and very original.

“Jimmie decorated the house himself,” Jean told me. “He was warned he couldn’t combine such warring elements as these, but I think it came out very well, don’t you?” The question was rhetorical—a courteous gesture—she didn’t wait for a reply. “Do you wonder I never want to go out, that I’m content to stay up here all the time I’m not working?”

We came into a completely feminine domain as we stepped into Jean’s bedroom; soft dove gray and primrose yellow with black and white hangings. Once again, it was Jimmie’s taste. “I thought I would hate it,” she said, “when Jimmie told me the colors he had selected. But when it was finished, I adored it.” The walls were in a rough wood like the main room, painted a soft gray, and from the windows once again we saw that amazing sweep of view, the full circle from this mountain top.

We made the grand tour. Jimmie’s room smacked of Africa again. Leopard skins were everywhere—on floor and chairs, and the terra-cotta corduroy hangings made a splendid setting for their barbaric beauty. “Jimmie shot them all on his safari,” Jean explained.

The bar was a sportsman’s dream of models, fish and tackle, gun racks, zebra skin everywhere and hundreds of tiny model heads of all the delicately beautiful creatures of the veldt spotted the walls.

“Jimmie wants to live in Africa,” Jean said, as if reading my mind. “He wants a farm there.”

“What about you?” I managed to ask.

“I wouldn’t mind living in Africa. Of course I haven’t been there, but from what Jimmie has told me Id love it. He’s dying to take me—not on safari, he says he’d be too nervous something might hap- pen to me—but to see the country. He has great passion for that country.” And, when we finished admiring, “Shall we go back to the withdrawing room?” she asked, like a well-trained little schoolgirl.

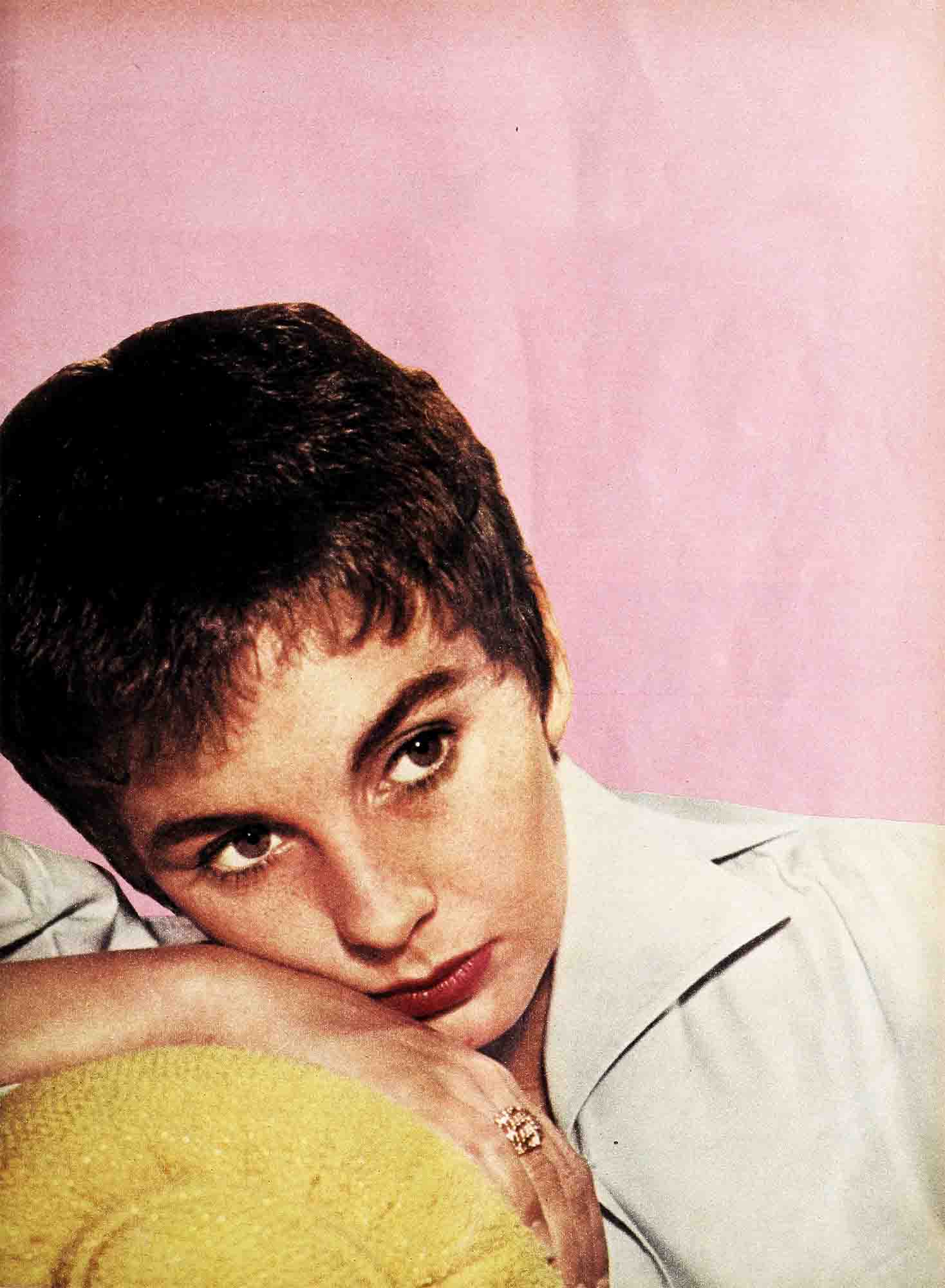

Marriage has made Jean look less like a school girl than she did a year ago. Her Roman haircut, shorter than the average boy’s, brings out an adult quality, completely sweeping away the immaturity that was formerly her characteristic. Her simple little black-and-white check dress, full-skirted and worn with flat-heeled shoes, was modern and in the sophisticated trend of the moment. The hazel eyes, heavily lashed, had a placid quality now, a contended quiet. We sat down opposite a Domergue portrait of Jean, which emphasized the change, the canvas was a round-faced child impatiently waiting to grow up.

“Are you happy?” I asked, “truly happy?”

“Oh yes, very . truly very, very happy.”

“You have everything you want?”

She smiled confidently. “Jimmie and I love each other. We are both successful. We have this little world we have made together, and we have the world down there when we want it.”

“But you’ve been separated so much—-the three years you’ve been married.”

“We have been separated a lot,” she agreed. “But that is an inevitable part of our work; we make the best of it. I suppose we’ve been apart more than most couples. Jimmie was five months in England with ‘Beau Brummell’—that was last Christmas. Before that, he was in Italy and North Africa for ‘The Light Touch’ with Pier Angeli. I’ve been on only one location trip with him, the one to Jackson’s Hole, Wyoming, for ‘The Wild North.’ But it could have been worse; I’ve escaped locations almost entirely except for a few days in the Mojave for ‘The Egyptian.’ And mostly I’ve been working while he has been away. I was on ‘A Bullet Is Waiting’ the last time he left.”

“But I hear he’s off again for Colombia, Bogota.”

“We have three days more together,” she protested. “And while he’s making ‘Green Fire’ I’ll be on ‘The Egyptian’ and after that I go into ‘Desiree’ so it won’t be too bad.”

I wanted to know if she stayed in her re- mote house all alone when Jimmie was gone.

“I didn’t want to move away,” she said, “so my secretary came and lived here the last time. The hardest thing about Jimmie’s absence, aside from missing him, is that I almost starve while he’s gone. You see, Jimmie is the cook; I know nothing at all about preparing food.”

Once again it was the topsy-turvy situation, with Jimmie the decorator and the cook and Jean the admiring bystander in the domestic arts.

“My hairdresser used to come up and make me a meal sometimes,” she said.

“I hear you keep open house for the British colony. That helps kill the time, doesn’t it?”

“Well, cocktail parties mostly, unless one of my guests happens to know something about cooking. This time it will be different; we have Rushton now. I won’t have to worry about getting someone to make meals. Jimmie brought Rushton back from England the last time he was there. He’d been with Jimmie ten years over there, a combined chef, dresser—oh, a little of everything.”

“Including a loyal and devoted watch dog when you’re alone,” I said, and she happily agreed.

A jet plane cut off our conversation, turning the acre of heaven into a roaring, vibrating bedlam. “That,” said Jean, “is our only intrusion. Fortunately it doesn’t happen too often.”

Jean’s story is a strange idyll—a child of fourteen who fell in love with a mature man, married and the father of two children. Jean was playing in “Mr. Emmanuel” with Granger’s first wife Elspeth March, when she first saw Granger in person. Jean played Elspeth’s daughter; she was a wide-eyed sprout and terribly excited, because she was a Granger fan. She tells me he’d wave at her condescendingly when they encountered each other. Her success in England had been a fairy tale sort of thing. She was one of the kids shipped out of London during the bombings, and when she came back she and her sister Edna had plans to open a school for dancing. Jean even had the license to operate the school when motion-picture talent scouts spotted her and she was cast in some child roles..She got splendid notices, this fabulous urchin that Granger, the man, scarcely noticed. A few years later she played opposite him in “Adam and Evalyn.” Jimmie had just been separated from his wife.

“It was the first time he noticed me as a woman,” she said. “We were going together from that time on, but not engaged yet.”

I recalled the time I first met her in London in 1945, the day she got the part of the slave girl in “Black Narcissus.” She danced around the tea table with joy, then suddenly she was fearful that she might not be able to do it. The second time I saw her, Elizabeth Taylor brought her to my house when she came to Hollywood after “Blue Lagoon.” That was in the fall of 1950. She was a bedazzled child with an autograph book in hand, collecting the signatures of the famous. “Tell me,” I asked her, “were you engaged to Jimmie at that time?”

“No, we were going out together, but we weren’t engaged.”

“You were very wide-eyed and happy then, as I remember,” I told her. “But nobody is happy all of the time—not all of your life—everyone has something to make them unhappy, everyone is miserable at some time or other.”

“I was utterly miserable in my first two years here,” Jean admitted. “First I was reluctant to return home because M-G-M had signed Jimmie to a contract. Then, when I got back to London, I learned that Arthur Rank and Gabriel Pascal had sold me to Howard Hughes in my absence. There was something slighting about selling me as if I were a piece of merchandise. Then I was brought back here for ‘Androcles and the Lion.’ But I was happy, too, because Jimmie and I were married in Tucson in December of 1950. And after ‘Androcles’ I was put into other things, but I was wretched in my work. There were law suits and I don’t know what. I wanted to go to New York but didn’t dare because I was afraid I’d be put on suspension by RKO if I went out of town and that would prolong a contract I wanted to get over with. But finally I was sold again and made ‘A Bullet is Waiting,’ which went very fast and is, I feel, a pretty good little picture. And now I’m in two things I like and everything is serene again.”

Then we had luncheon, with Jimmie Granger tossing the splendid salad, which he served with just the correct chilled white wine. We talked of his coming trip, of his preoccupation with foods and the preparation of them, and he told of the differences in his and Jean’s tastes:

“She hates caviar and I adore it,” he said. “I like a baked potato stuffed with caviar and she won’t touch it. But she dotes on fish ’n’ chips and she’d die for winkles—a sort of shell-fish they sell on the streets in England in little paper bags, much as you sell hot roasted peanuts here. You hook them out of the shell with a pin—a very low taste,” he finished, with an indulgent grin.

The household animals moved in on us as we sat around the huge living room table, which is covered with tarpon hide and rimmed in ivy green leather, two toy poodles, Betty and Beau, mother and son, and two identical Siamese cats named Traybert.

“We have one name for the two of them,” Jean explained, “since we can’t tell one from the other. It’s a combination of Spencer Tracy and Bert Allenberg, and they both answer to it. Jimmie is full of contradictions; he announced he’d never, never have a cat in his house, then sent me these. And when Betty had three puppies, they were apparently all given away. Then, weeks later, back came this little fellow with a note, ‘I hope you haven’t forgotten old Beau,’ and he’d been housebroken and things. It was wonderful.

“He does thoughtful things like that. One of the unhappy things in my life was the fact that my father died before I made my success—he never knew. The only picture we had of him was one Mother had. Well, when Jimmie was in England this last time, he got the picture from Mother and had it copied for me. I’ll fetch it.” She came back with a photograph held to her heart. “Here he is.”

“Isn’t that a fine face?” said Granger.

It was a very fine face with a firm square jaw, balanced eyes, intelligence and a sane hold on life.

“He was a swimming champion, too, as well as a schoolteacher,” Jean explained. “He represented Britain in the Olympic Games of 1912. I was just sixteen when he died.”

When I commented that they had as many animals as Elizabeth and Mike Wilding, Jean said, “Not quite. They have four dogs and two cats, and the James Masons have, oh, I don’t know how many cats and a dog, an Alsatian.” The phone rang. “It’s Liz,” Jean told her husband. “They want to know if we’re coming over for dinner tonight.”

Jimmie said, “Say we’ll let them know later on.”

“But they want to know how much meat to take out of the deep freeze.” So Granger nodded: “Okay, tell them we’ll be over.”

Liz and Jean have been fast friends for years, and Stewart Granger and Michael Wilding have been pals for even longer. Jean spoke of Jimmie’s children, who spent three months with them last summer.

“It was a delightful time,” she said. “They’re splendid children, naturally naughty at times but beautifully behaved in the main and very obedient. They loved it here. Lindsay is almost seven and Jamie is over eight. They met all the youngsters, but I think the Niven boys were their favorites. When the time came to go, they hated to leave, and yet, they were glad, too—a mixed-up emotion. That old pull of home and Mother is very strong.”

There is both a difference in age and a difference in backgrounds between Jean and her Jimmie. He admits he was a spoiled brat—there was just himself and a sister. He had begun training for a medical life but abandoned it.

“I had an uncle who was a saint, a general practitioner,” he said. “I’d seen the slavery of all that, so I wanted to be a specialist. But one day my father told me he couldn’t afford to let me specialize, as it would take years and years before I was earning money.

“I got into the theatre in a strange sort of way. I cut my finger and went to a doctor; the doctor’s wife was teaching acting. That’s how it began. Ellen O’Malley talked me into it and got me a scholarship at the Webber-Douglas school of dramatic art.

“I was eight years in the theatre before I made my first film. I’d worked in various repertory theatres and at the Old Vic, and I’d played ‘Rebecca’ on the West End stage. Then I tore up a forty-pound-a-week contract with Basil Dean to play Lord Ivor Cream in ‘Serena Blandish,’ with Vivien Leigh, for a salary of three pounds a week. It was the best move I ever made. Now, Mike (Wilding) comes from a family of actors. His grandfather was a singer and an actor, but the two of us worked extra in films because someone told us it was a fine way to meet beautiful girls. Mike was really out to be an art director.”

And we spoke of Vivien Leigh, her beauty. talent and the tragedy of her life. “Vivien was getting three pounds a week in England when she persuaded Laurence Olivier to accept the role in ‘Wuthering Heights,’ which he wasn’t very eager to do. Vivien had made up her mind she was going to play Scarlett O’Hara and laid her plans well. It was priceless the way she put it over. She’d practiced the Southern accent until she had it to perfection, and then she maneuvered to meet David O. Selznick. She simply poured on that Deep South, and of course, Selznick immediately suggested she test for the role of Scarlett. Vivien told him precisely what scene she wanted to make and that she already knew it. The rest was history.

Then Jimmie left for a conference with Rushton in the stainless steel kitchen beyond a screen of tropical plants, and Jean and I were alone.

“I’ll never forget Vivien Leigh,” Jean said. “The last time she was here, she was such a tragic figure, ill and all. She took me off in a corner and we had a long talk about life in general. She said: ‘If you’re happy, don’t give up anything because of a career.’ I guess you might say I’ve made that my rule for living.”

Winding down the perilous path from the Granger’s house, I discovered I thought of Jean as a happy woman, with a calm, quiet capacity for enjoying the solitude forced upon her by separations from her husband, the music’ that fills her every waking hour, the fast friendships that she’s formed in Hollywood. For her the words in the dictionary apply.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments