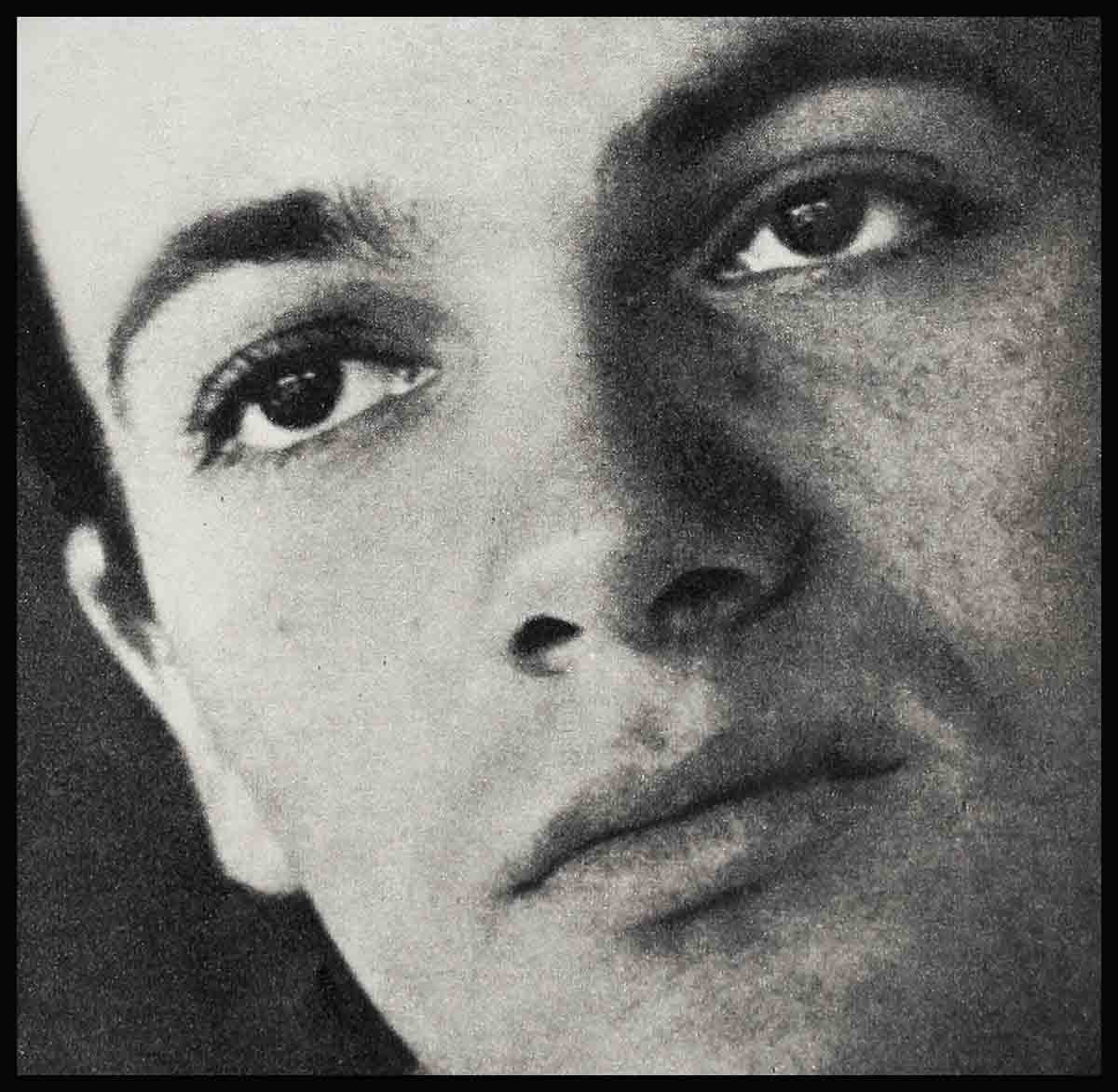

The Night I Almost Got Killed—Tommy Sands

Tommy Sands lit another cigarette, blew a smoke ring—and all of a sudden I noticed it. All the times I’d seen Tommy, and yet I never saw it before.

“Why Tommy,” I blurted out, “that scar on your lip—how’d you get it?”

Tommy squirmed in his seat. He took another drag on his cigarette.

Finally he said, “Well, Peer, it’s a long story. . . .”

I waited.

“I never told anyone about it.”

“Yes?” I encouraged him.

“And my mother doesn’t know anything about it . . . I’m sort of ashamed of it.”

“Don’t tell me if you don’t want to, Tommy.”

So, of course, he began. “Well, there was this girl I was going with and my mother was against it. No, not against the girl—she was a wonderful person and my mother liked her very much. But this was a couple of years ago, and Mom thought we were too young to be so serious. Her mother thought so too.

“So finally I had to give in and agree not to see the girl—at least not so often. But this was very hard to do.

“And one night I missed my girlfriend so much I just had to see her. We made a date for a movie. She told her mother, but I figured I’d better not tell mine. I figured I’d avoid a lot of trouble if I just said I had a rehearsal on. . . .”

How it all began

The evening started out pleasantly enough, this date Tommy had with the girl whose initials were M. H. He didn’t want to have her name revealed in print because she may be married by now, and her husband might not believe the story any more than her mother did when Tommy tried to explain the bloodstains on her dress. . . .

They had gone to a show and stopped for a hamburger and milkshake at a drive-in. About ten-thirty they headed for her home.

Two miles from their destination, they had to stop at a traffic light. While Tommy waited for it to turn green, a car bumped into his, from behind.

They were shaken up a little but Tommy felt sure his rear bumper must have absorbed the shock and prevented any damage. He stayed in the car. The light was still red.

When he looked back into the rearview mirror, however, he saw the other car pull back a few feet, and then jam right into him again. Obviously this time it was intentional!

Boiling mad, Tommy threw open his car door, jumped out, and squeezed through the narrow space between his car and another one parked to the left of him, heading for whoever hit him.

He’d taken less than three steps when he was hit over the head with a blunt instrument.

His vision blurred for a moment as he went down. But he quickly managed to get up and fight back at his assailant—when a second fellow attacked him from the other side. Two men must have jumped out of each side of the car, simultaneously. . . .

Now they fought him together.

Tommy shouted for help but the driver parked next to him pushed down on the accelerator. He didn’t want to get involved.

M.H., ignoring the danger to herself, was out of the car now. Gripping her purse tightly she swung it with all her strength. The contents—lipstick, compact, keys and other paraphernalia—made the purse into a powerful weapon. The fellow who was hit cried out in pain and then shoved her back against the car. She kept on fighting while he pushed her back.

Meanwhile Tommy took the worst beating of his life. The instant one man relaxed or turned his attentions to M.H., the other would pounce on him again. Although they were older, taller, and obviously a lot stronger, he had one advantage in his favor. When he was a boy in Chicago, his father, Benny Sands, had befriended a lot of fighters who lived in the same hotel where he and his family stayed. One of them, an ex-heavyweight contender had taken Tommy under his wing and had shown him some pretty good punches. But he’d only taught him how to fight clean. When the fight got dirty, Tommy was unprepared.

Finding themselves in more trouble beating up Tommy than either of them had anticipated, the taller one pulled a knife. Tommy saw it coming at him and ducked, but not fast enough. The blade cut his face, near his mouth.

Tommy got up and charged the fellow who was turning toward M.H. again. He grabbed his shoulder, tossed him around and hit him in the face. He thought he heard something break. It could have been the other man’s nose. . . .

Again Tommy felt another sharp pain in his shoulder. He didn’t know what caused it as he turned, swinging his right fist.

Tommy passes out

It never reached its mark. The first man had hit him across the neck . . . Tommy went down.

He doesn’t remember much of what happened after that. He felt pains; he couldn’t see; noises seemed faint and far away. The beating and kicking didn’t stop. He was sure he was dying. . . .

And then it was very quiet. He had lost consciousness.

Hours seemed to have passed by before he came to again. Actually it was just a few minutes later. M. H. was leaning over him, crying hysterically, wiping blood from his face.

Tommy no more knew why the fellows had suddenly left than why they had attacked him in the first place. He thought he smelled liquor on their breaths which might have explained their insensible behavior. But he was not sure.

He was too weak even to lift his arms. It took all M.H.’s support to help him back into the car.

“Can you drive?” he asked her hoarsely.

She shook her head. “No. I can’t. I’m sorry . . . Oh, Tommy, I’m so sorry. . . .”

Gently she closed the door on his side, walked around the car and climbed in next to him. Tommy turned the ignition key. His arm hurt, but it wasn’t broken. Blood was still gushing down his face, over his new suit, the upholstery, and clung to his hands, her hands, her dress.

“What are we going to do?” M.H. asked desperately.

The motor was running, but Tommy couldn’t think straight. He didn’t know what to do.

“Maybe you’d better see a doctor,” she whimpered.

Tommy pulled away from the curb. A block away they saw a girl crossing the street. Tommy stopped next to her to ask for a doctor. When she got a look at his face, she let out a scream, and ran off.

The next pedestrian, a man in his fifties carrying a newspaper under his arm, was more helpful. He told him how to get to the emergency hospital, a mile away.

The doctor took eight stitches near his mouth and four on his head. Tommy was bruised all over, but there were no broken bones.

Groggy and weak, Tommy left the emergency hospital an hour later, leaning heavily on M.H.

If he thought his troubles were over, he was wrong. They had only started. . . .

What her mother thought

M.H.’s mother let out a shriek the minute she saw her blood-spattered daughter. For a moment Tommy thought he was going to get beaten up all over again, and at this stage he couldn’t have defended himself against a five-year-old.

“What did you do to my daughter?” she screeched. “You monster . . . you terrible boy . . . I never wanted her to go out with you. . . .”

Tommy tried to explain. “We were sitting in the car. . . .”

“I bet you were. I just bet you were!”

“But Mommy . . .” M.H. cut in.

“You be quiet!” the mother said. And, turning back to Tommy, “You were in a brawl, weren’t you. . . .”

“But Mrs. . . .”

“Don’t you ‘But Mrs.’ me,” she shouted. “Look at my daughter. Look what you’ve done to her. I should turn you over to the police, you . . . you. . . .”

Tommy couldn’t fight back. He was desperately tired. Mainly he had wanted to explain for his girl’s sake, because of what her mother had thought so far, and what she might come up with next!

Slowly and with much effort he turned and walked to the door while M.H.’s mother was still shouting and gesticulating wildly.

Tommy stopped briefly. “I’m sorry,” he said weakly. “Honestly, I’m sorry. . . .”

And then he left.

It was only a ten-minute drive to his own home. Ten awful minutes in which Tommy worried what he could tell his mother. If M.H.’s mother didn’t believe him, would she? Seeing him with blood all over him, there was no telling what she would think, particularly if she knew he’d been with a girl.

Suddenly he got an idea. He pulled into a gas station, got out of his car and headed for the pay-phone. A few seconds later he heard his mother’s sleepy voice.

“I had a little accident, Mom. Nothing to worry about . . .” he assured her.

Mrs. Sands pictured a dented fender or scraped side or something like it. Yet while she hadn’t been prepared for bandages around his jaw and head, and blood spilled all over his new suit—his appearance didn’t come quite as much of a surprise to his mother as it did to M.H.’s mother. Then, in order to have more time to think instead of giving himself away by sputtering out all about the fight, Tommy told her he was exhausted and needed some sleep. Mrs. Sands could see that was true, and helped him to bed.

“The next morning,” Tommy recalled, “nothing looked quite as black. I put my clothes into a suitcase so Mom wouldn’t be reminded of what she saw the night before, and took them to the cleaners myself. The cut on my face, I told her, happened during the accident when the other car and mine collided—which in a way wasn’t so far from the truth. I knew she’d worry a lot less when I went out ereaict if she didn’t know all the details. . . .”

When Tommy finished his story, I asked him if I could write it up. I was sure, I told him, that his fans would be interested in hearing about the night he almost lost his life.

Tommy wasn’t sure. After all, he hadn’t told his mother. . . .

“Tell you what, Tommy,” I said. “I won’t write it unless you tell your mother first. Matter of fact, why don’t you tell her anyhow? You’ve had it on your mind these last two years. . . .”

Next day I got a call from Tommy. He told his mom, and it turned out that she knew it all the time! She just didn’t want to add to his misery.

“Maybe,” Tommy concluded, “you shouldn’t call the story The Night I Almost Lost My Life—it’s more like the night I almost lost my mind!”

THE END

Tommy will soon appear in MARDI GRAS for 20th-Fox.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1958