My Country Or My Child?

I love America

and England, too-but

I am Italian.

My country is Italy,

I could never leave it.

Whatever happens,

I can not change.

Was ever a woman faced with

such a problem—

having to choose between

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Loren spoke those touching words on the preceding page in an exclusive interview Photoplay a few months ago. In that interview, she expressed her hopes and fears about having a baby, and revealed the unique and tremendous decision a pregnancy would force her to make. Now in view of husband Carlo announcement to our photographer that Sophia is pregnant, plus the report that he mil seek French citizenship so he can legally marry her in France, Sophia’s story is more touching and newsworthy than ever.

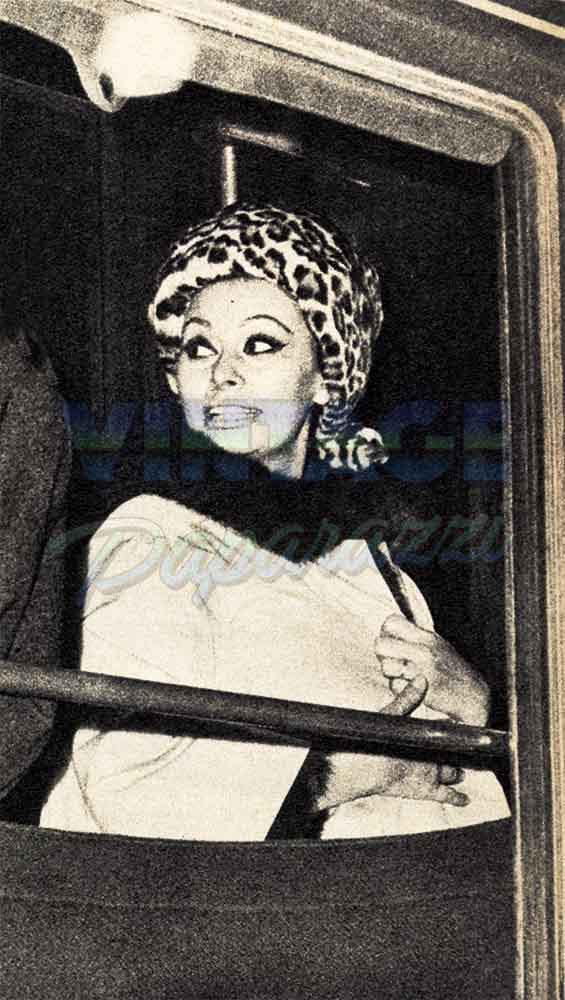

The black Citroen scudded along the crowded road to Rome. In the back, beside me, sat Sophia Loren. She was dressed entirely in black, her favorite color: black jumper, black skirt and black shoes. She even sported an attractive and fashionable black wig.

She wore no jewelry—not even a wedding ring, for according to Italian law she is not married. But she needs no adornment, Miss Loren. She is a real woman, not a decorative doll. A sturdy wayside poppy in an industry devoted to forced roses—that’s Sophia.

I had flown to Rome to seek the answer to two questions: Was it true that she was considering abandoning her Italian nationality so that her Mexican marriage to producer Carlo Ponti could finally be recognized? And what was she planning to do about the child she so desperately wanted?

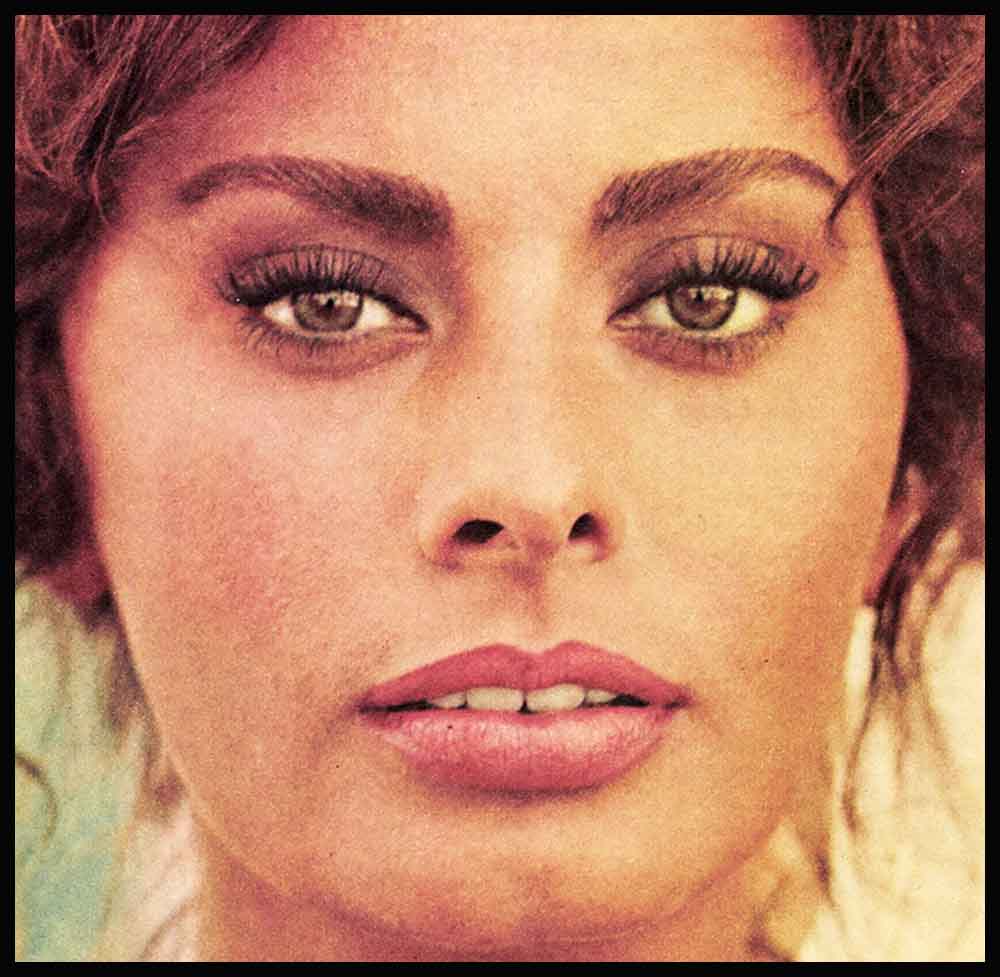

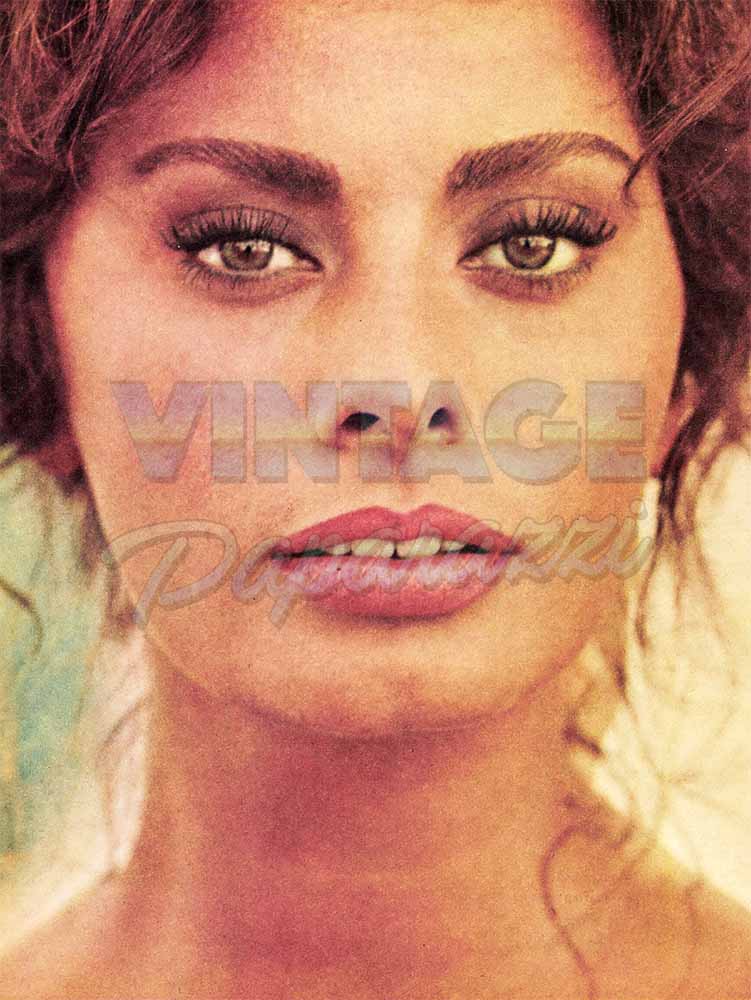

Sophia, with typical courtesy, had come to meet me. And as I looked at her sitting in the car, at her too-big eyes, too-wide mouth and too-large teeth, I thought of what her friend Vittorio de Sica once called her: Much woman. And much woman she is.

But this is a time of heartbreak for the girl born an urchin in Naples. There is, she now knows, no hope at all of her Mexican proxy marriage to Carlo ever being recognized in Italy. (He was married before, to Giuliana Fiastri, and his Mexican divorce is not acknowledged by Rome.) On top of this, Sophia has lived with a threat of prosecution for bigamy for six years.

It may never come to court. But should she have a child, there is no doubt in her mind that they will throw the book at her. And the penalty could be up to five years in prison! Incredible, but true.

Not another illegitimate child

Sophia herself is illegitimate. The last thing she wants to do is bring another illegitimate child into the world. But what can she do? She is twenty-nine now; she cannot wait forever. It looks as though the only answer is for her to abandon the country she loves; to quit Italy and take out another nationality. But could she do it? Could she, the woman who is as Neapolitan as spaghetti, who pined for her beloved Bay of Naples all the time she was in Hollywood, be truly happy as anything but an Italian?

That is what I had come to Rome to find out.

“I am not bitter,” she said, looking at me with those great eyes. “This thing has been hanging over my head too long for that. But I just don’t know what to do. Carlo says we may have to take out different nationality. But that is not easy. It takes ten years to become Swiss, for instance. And, of course, one cannot change one’s heart. Even if I became Japanese, I would still feel Neapolitan.

“De Sica laughs at me,” she said, “because there is only one man in my life. I met Carlo when I was fourteen and a half, you know, when I was skinny and unattractive. And there has never been anyone else. We are a one-man family. My mother met my father and never loved again. My sister Maria met Romano and knew he was the one. I met Carlo.

“In a way we are lucky, we Neapolitans. We grow up early. We do not waste time dreaming of handsome young men with fast cars. We know sex and passion do not last long. Only emotionally immature people expect that they should.

“People say I married Carlo because I wanted a father (Ponti is nearly forty-nine, twenty years her senior). Well, that is partly true. But I married him for other things, too. For simpatico, for tranquility, for security. Remember, my mother and father were not married and I needed that security. Carlo gave it to me. And since I married him I have never been unfaithful to him. And I never will. There are many suitable men but very few suitable life partners.”

She gazed out of the window of the speeding car. There was a half-smile on her face.

“You know,” she said, “because of my parents I grew up hating men. I never forgot how one day when I was very young my father wired my mother begging her to go and rescue him from some woman with whom he was involved. My mother didn’t go and my father married the woman. For a child it was all terrifying. Even today when I see my father I can never be relaxed with him.

“My mother, you know, is still full of bitterness. She keeps to herself. And in her mind she keeps going over old grudges. She was a truly beautiful woman, you know, and a fine pianist. But my father gave her a had time. We were very poor.

“Poverty may spur ambition, but it also makes people angry. I grew up to the sound of anger and screams. I try and try but I can never remember any of the happy things that must have happened in my childhood.” She paused then, silent.

Suddenly I saw her eyes were moist.

“A child,” she said. “That is what I want more than anything else in the world. But it is impossible. We are not legally married; the child would be illegitimate. And Carlo would need his wife’s permission to pass on his name to any child we had.

“There was a train crash here not long ago, and a little boy was orphaned. I hoped to adopt him. but at the last moment they found he had an aunt. It was very, very sad. I cried for hours.

“I envy any woman—the humblest peasant here in Italy—who can have a child in the tranquility of a marriage no one can challenge. We Neapolitans feel strongly for children, you know.

“Fortunately my sister Maria has a wonderful baby, Sandra. I see her every day, She is just nine months old and an enchanting child. She helps take my mind off my own sadness.

“I am her godmother, and they even made trouble for me over that. The Vatican didn’t approve of my taking part in the baptism; others wrote that it was terrible that a public sinner like me had been given a position of such responsibility.”

She shook her head. “Trouble,” she said. “Nothing but trouble.”

I took her hand. I have known her, I suppose, for ten years. We have been in Hollywood together, in Vienna, in London and in Paris. I have been swimming with her from the big launch she keeps just outside Rome and I have been driving with her around Madrid. I have seen her weather the storms and the hurts and the sadnesses and come through smiling.

I saw her when she came back to Rome from Hollywood three years ago, when her stock was low indeed after a series of mediocre films. When the Outlook seemed very black.

And I was with her when Cary Gram telephoned to tell her she had won the Oscar for “Two Women”—the film in which, her stunning figure swathed in rags, her hair combed with a garden rake, stripped of all makeup and artifice, she turned in a performance of staggering virtuosity. A magnificent performance.

“Fighting for something wonderful”

Today Sophia Loren is a super-star, able to earn a million dollars a year and more from her films. She has been hailed by shrewd observers such as Stanley Kramer as potentially one of the greatest actresses in the world.

No female star is more loved. Cary Grant adores her; so does Peter Sellers; so does Bill Holden. Gable worshipped her.

And every day, in the mail, letters pour in from all over Italy. The little people are on her side.

“Perhaps.” she says, “because I am fighting for something rather wonderful: the right to be in love.”

We drew up outside my hotel and she looked around her, at the bustling traffic of the Via Veneto, at the smartly dressed men and women thronging the sidewalks and sipping early evening aperitifs at Doney’s and the Cafe de Paris.

“This is my country,” she said. “I love it. I could never leave it. I love America. I love England. But I am Italian. What- ever hap pens. I cannot change. Was ever a woman faced with such a choice—my country or my child? I do not think so.”

And she shook her head.

—By Charles Portland

Sophia’s in “Yesterday. Today and Tomorrow,” for Embassy. Her next is “Fail of the Roman Empire,” for Paramount.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964

No Comments